Owen Harvey, Jess T Dugan, Emma Hardy, Ayomide Tejuoso, Annie Wang and Georgie Wileman reflect on the notion of ‘self’

Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘self’ as “a person’s essential being that distinguishes them from others”. What creates this essential being is, however, harder to define.

Perhaps, to coin an overused phrase, it is what ’s inside that counts. Do our emotions, ideas and even our politics create our sense of self? Maybe how we appear to others – our clothes, our hair, the way that we speak – plays a role.

Or is it external factors that define us? In a capitalist society, can our sense of self ever be truly divorced from the circumstances of our birth? If not, then perhaps our class, race, gender or the place we call home are the biggest factors to consider. The most likely answer is that our essential beings are a combination of all of the above.

Here, Owen Harvey, Jess T Dugan, Emma Hardy, Ayomide Tejuoso (Plantation), Annie Wang and Georgie Wileman offer their thoughts on the concept of ‘self’ as a component in their lives and work.

Owen Harvey

I took this image in 2016 for my documentation of the UK skinhead scene. I’d meet people and go for a walk with them, try and get a sense of who they are and then shoot images throughout the day. Some of those walks led to relationships, others would just result in the one shoot. I was interested in the skinhead scene and what that represented. I’ve always been interested in how people express their identity through their clothing and find their ‘home’ in their subcultural groups. This portrait was on the final roll, near the end of the day. The next day, I flew to America and this shot sat at home unprocessed for three months. When I got back, this image stood out to me immediately. There’s both strength and fragility in it – the bruised leg, cut knuckles, confrontation – and equally a sense of vulnerability.”

Jess T Dugan

I have always created self-portraits as a way to understand myself, my place in the world, and my relationships with others. Some of my earlier photographs asserted my identity as a queer and non-binary person, while my more recent self-portraits have taken on a different kind of interiority, exploring more expansive notions of personhood. As I age, I am increasingly thinking of my photographs as an archive of my own life, a documentation of myself exactly as I am at a specific moment in time, knowing I will continue to grow and change and evolve. I made this photograph early in the morning in the bay in Provincetown, Massachusetts, a place that has been dear to me for the past 20 years. For just a moment, the clouds parted in front of me, and the sunlight poured through and illuminated my body against the darkened sky.”

Emma Hardy

As the photographer and the daughter and granddaughter of the two women appearing in front of my camera, I’m the third generation of women participating in this image. And to this extent, I consider it as a portrait of myself. My presence, my gaze, my reflection of my immediate female heritage is as close to a self-portrait as possible. The intense intimacy is palpable. I’m intrinsic to it. I’m both mirror and reflection. My mother gazes at me as I gaze at her. There’s so much in this exchange: vulnerability, strength, resilience. I also recognise resignation – or is it acceptance? – in my mother’s eyes. My mother was 80 at the time of this image. Ageing has challenged her and yet to the viewer, she is every bit as beautiful as she once was. She is grace and defiance. I see you and I see myself in you.”

Georgie Wileman

Pound for the Meter is a documentation of my aunt and cousins, living in government housing and on the breadline in the UK. Julie lives with an intellectual disability, which her children have also inherited. I put a lot of responsibility on myself to accurately and respectfully represent my family’s world, something that’s made easier by Julie’s unapologetically authentic presence of self. I have never photographed someone who is so uninhibited and unaware of my camera before, or someone who has no real interest in seeing their portrait once it’s been taken. It makes me smile every time I turn my camera to show Ju her photograph – the same indifferent ‘Oh yeah, yeah’ every time. I’m never quite sure if she’s actually looked. Her honesty to self is so beautiful to me, unaffected by her surroundings, Ju remains Ju. As a photographer and Julie’s niece, it’s an honour to document her.”

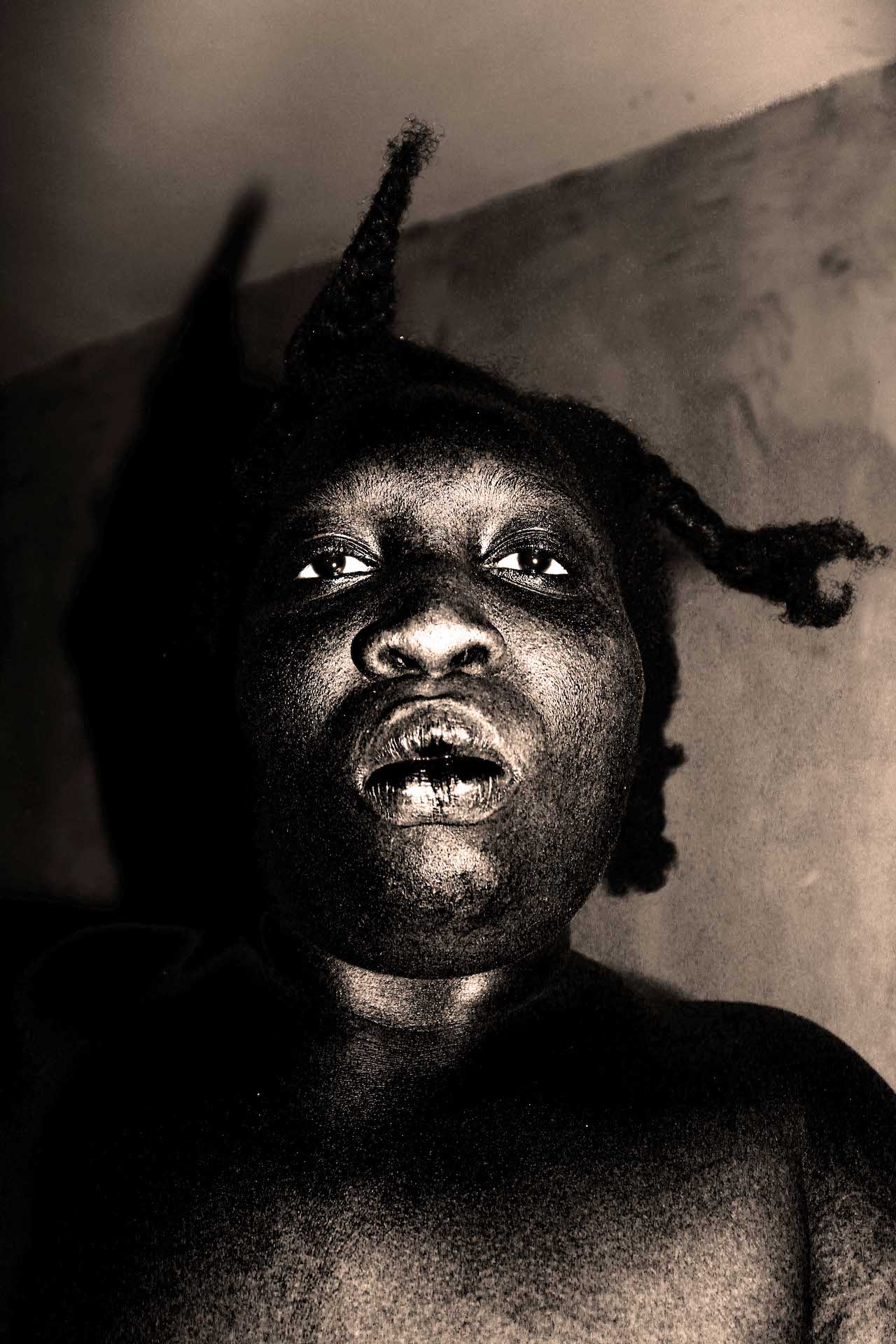

Ayomide Tejuoso (Plantation)

The image Black dust; Blue thunder is from my project Black sex is forbidden; Black death is permitted. It is an intentional study of my body and my relationship with Black femininity, depression and nihilism. Following my reflections on racism and the dehumanisation of the Black woman body, the image was a stop in time, a detailed archive of the pain I experienced as a young Black woman in the strain of Nigeria and the isolation of France.”

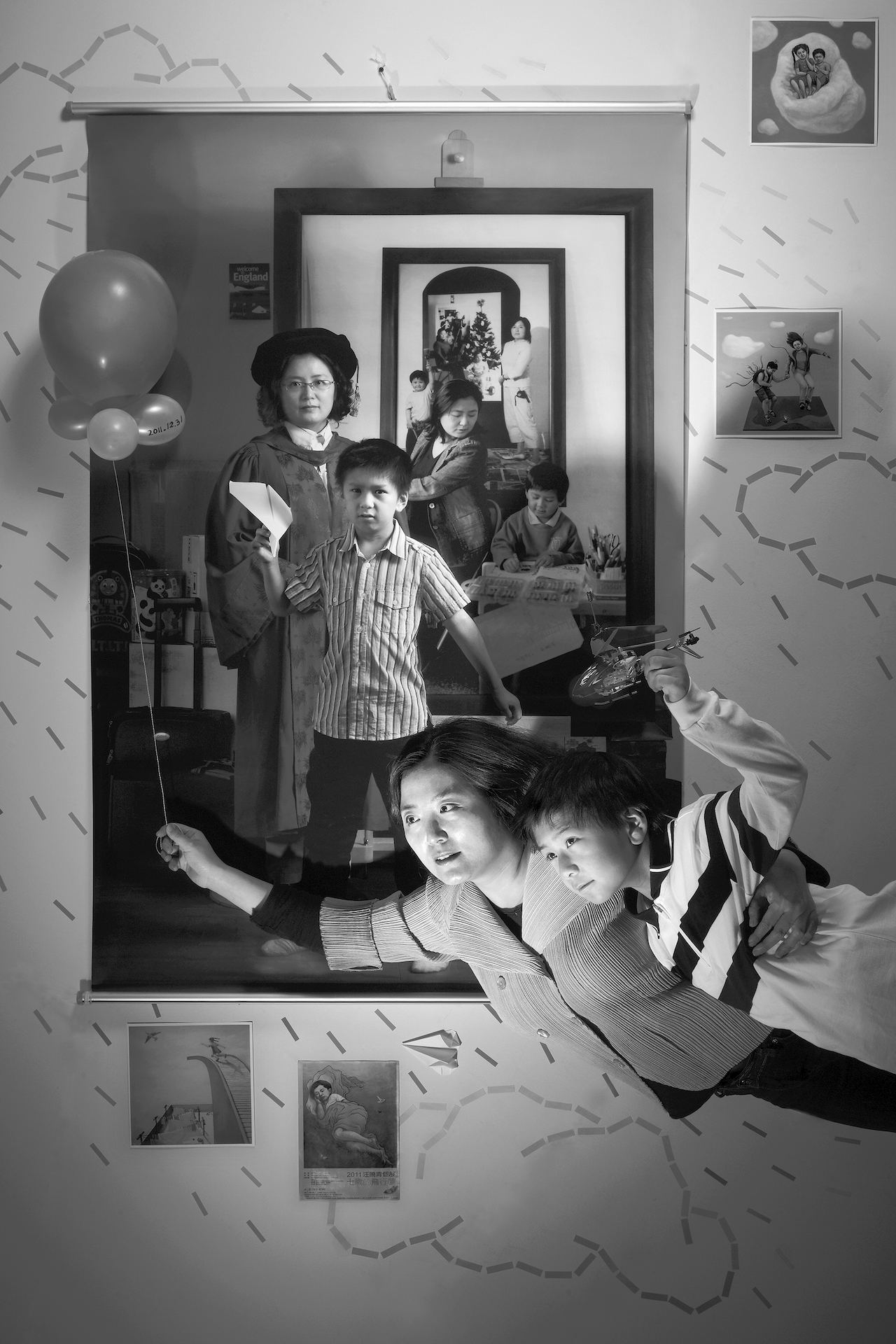

Annie Wang

In 2000, I was burdened with pregnancy pains and the fear of losing my sense of self, so I attempted to use art creation to preserve it. Starting from the first self-portrait taken in 2001 on the day before I was due to give birth, my son and I have taken a new photo together in front of the previous photo every time we’ve had a common life experience. This picture is The Mother as a Creator No 8: Making Dreams in 2011. Here I photographed my expectations from a different angle, I let crisis become a turning point and my ideals take flight by working to achieve my dreams. I have created 12 photographs for this project over 22 years now, and will continue the mise en abyme autobiographical approach. I hope I can reverse the stereotype that mothers must sacrifice themselves, and thereby help redefine motherhood.”