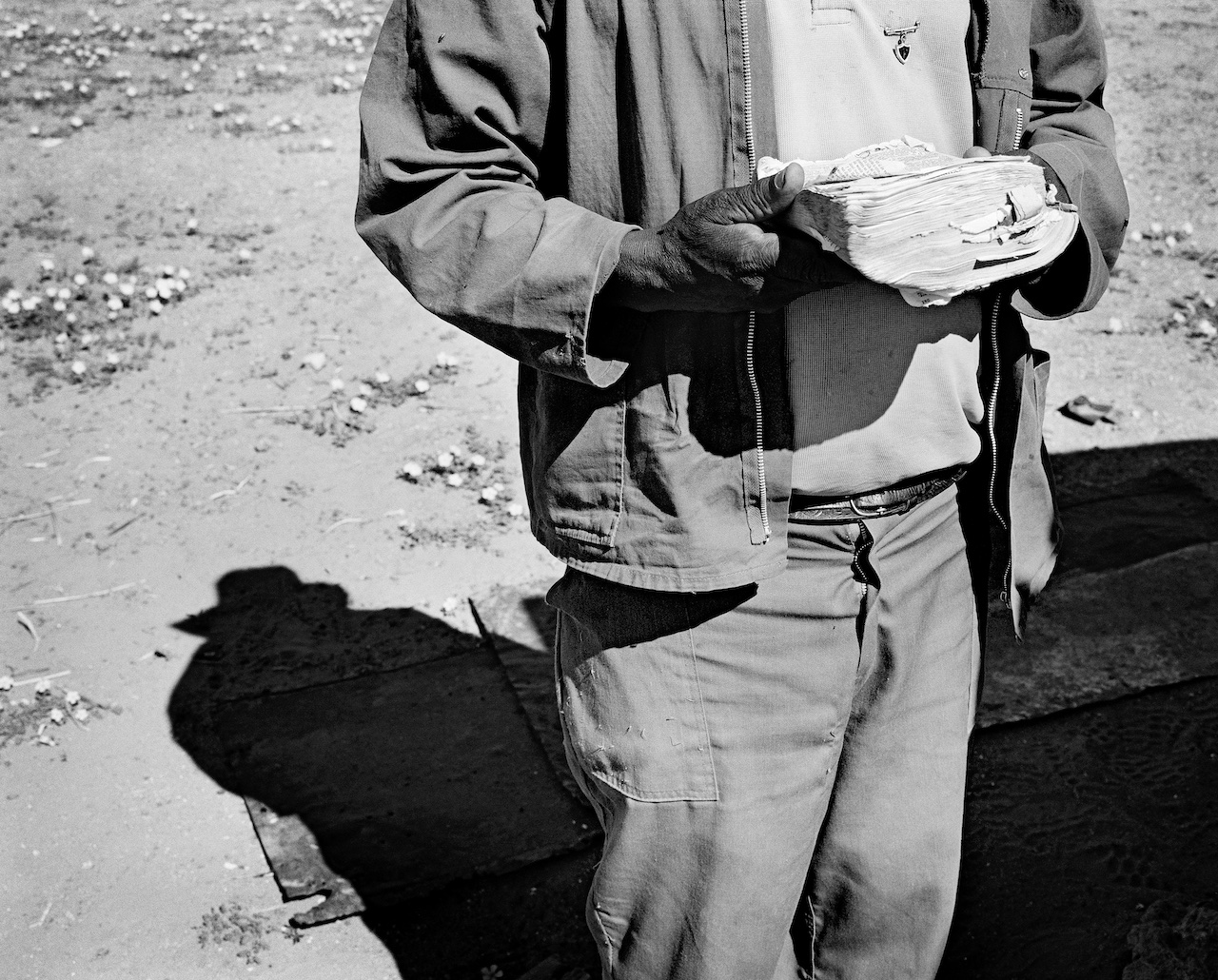

Roadside stall on the way to Viana, 2007 from the series Terreno Ocupado © Jo Ractliffe.

The South African photographer reflects on her Deutsche Borse-nominated publication, Photographs 1980s – now

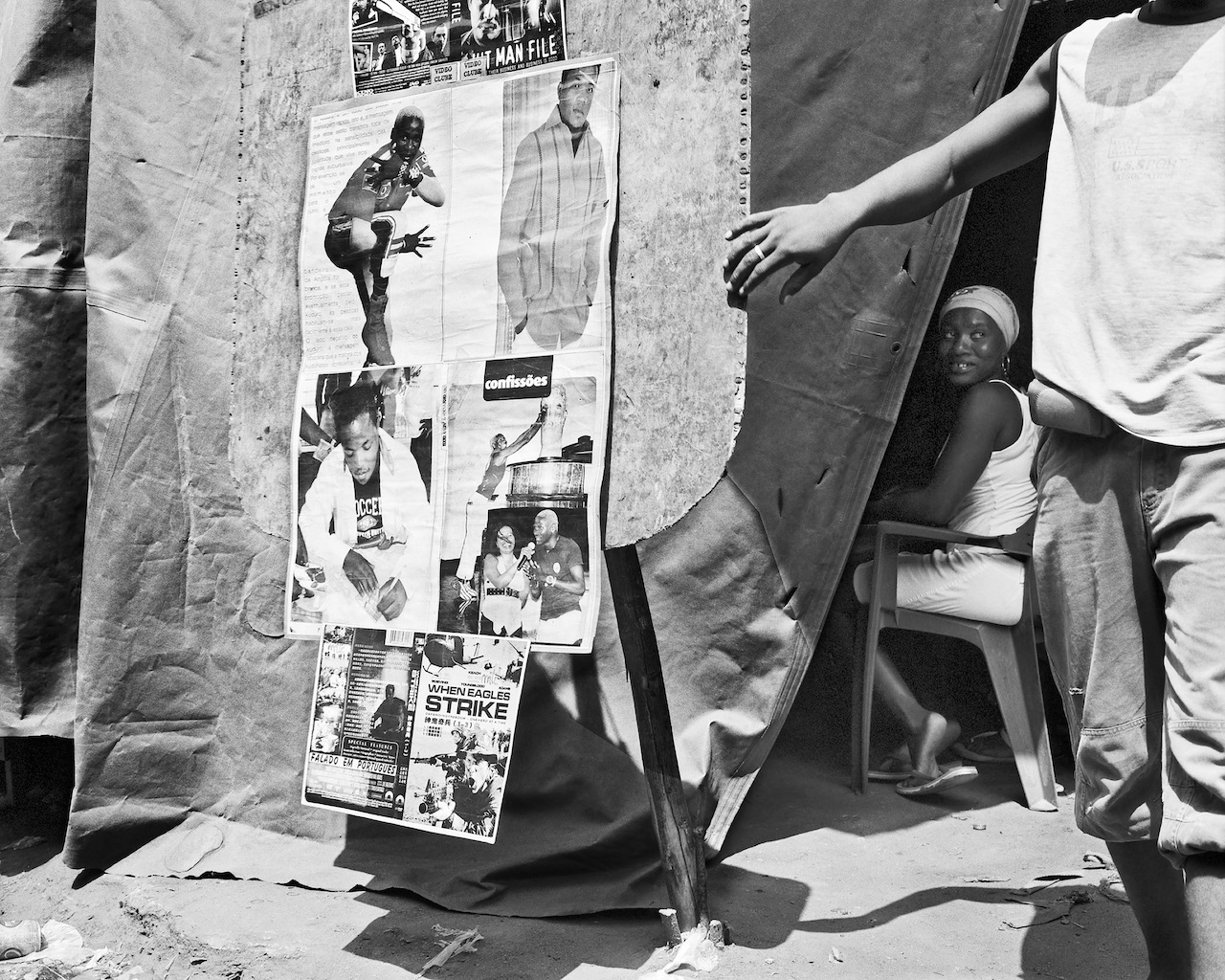

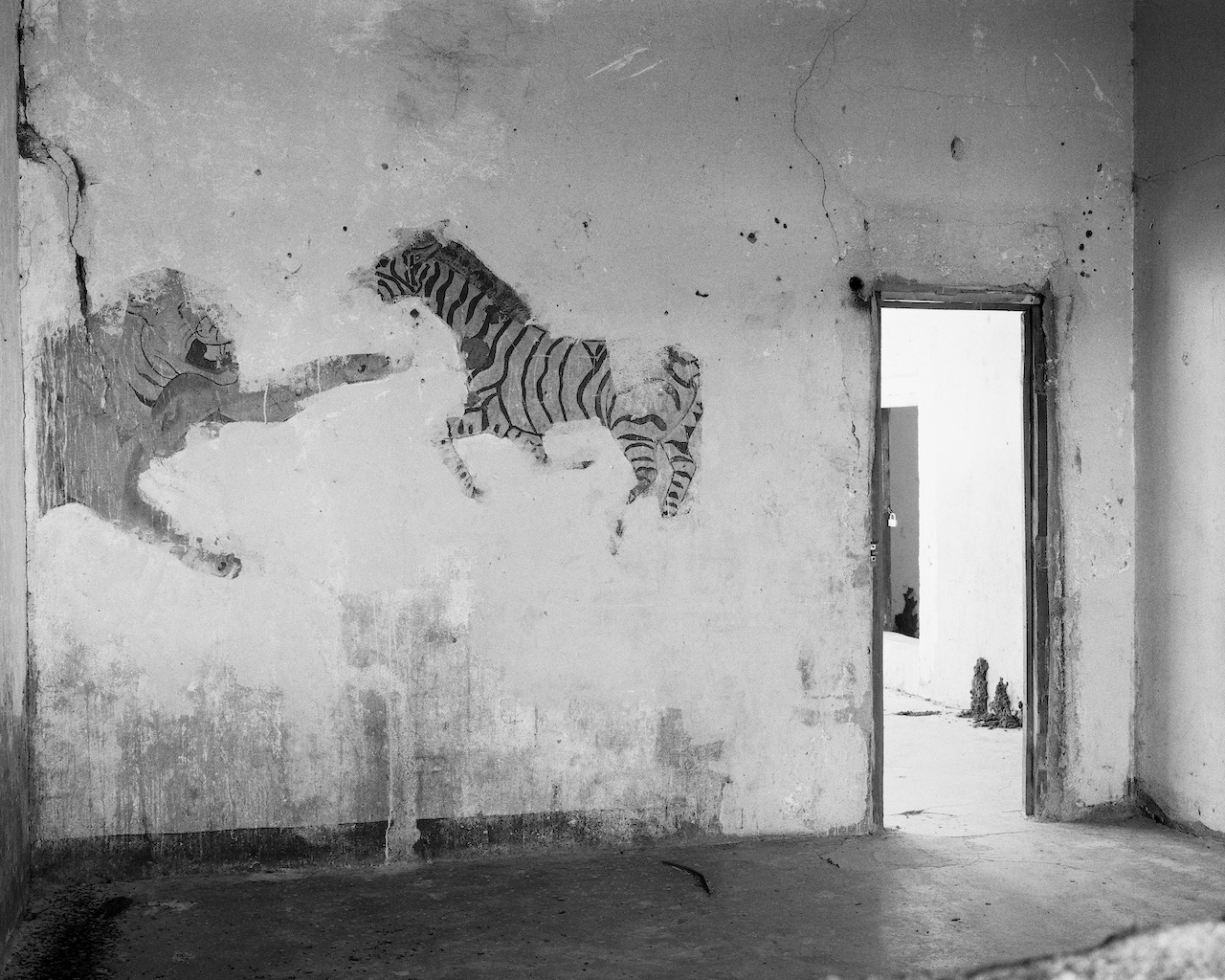

Jo Ractliffe’s exhibition – Photographs 1980s – now – is restrained, enigmatic even. The monochrome images were taken in South Africa from the 1980s, and in Angola from 2007-2010. These are periods in which both countries went through, or recovered from, violent change. This isn’t directly evident. Most of her images don’t show people. If they do, they don’t show their faces, or they show them looking elsewhere. Many of her photographs are landscapes, in which human existence and violence is discernible only through traces. “A lot of my work is [made] in places where terrible things have happened,” says the South-African artist “But where there is no blood on the ground.”

Her exhibition, currently on show as part of the Deutsche Borse Photography Foundation Prize at The Photographers’ Gallery (TPG), doesn’t provide easy answers. There is a short text at the start and brief captions beneath each image, often simply stating the date and place it was made.

Photographs from different times and locations are freely mixed in the hang. Where images from specific bodies of work are grouped together, there’s no explanation of the series or project. Viewers are largely left to draw their own interpretations, and that’s deliberate. If you give too much information, people stop looking and start to read, says Ractliffe, “then they look to understand what it is they are looking at”.

“That’s not my experience when I’m photographing,” she points out. “When I’m photographing, I don’t know what it is that I’m looking at. I have to rely on my own way of seeing things and discovering meaning in the space, learning to read the space. And I think that’s much more interesting for a viewer, to have to come in and trust themselves.”

Co-published by Steidl and The Walther Collection in 2020, Jo Ractliffe, Photographs 1980s – now, is the book that won her the Deutsche Borse nomination. It provides answers but also many more questions. A hefty 470 pages long, it includes work currently in the TPG show, but also much more. Projects such as Real Life (2002-2005), made in Ractliffe’s own backyard; or Everything is Everything (2017) and Signs of Life (2019), more recent work which includes personal images, one-offs, and photographs that refuse to be edited out.

The book is divided up into series, each introduced by Ractliffe, but her writing is informal and diaristic rather than authoritative, even when introducing topics such as the Border War between South Africa and Angola. She freely admits to uncertainties. Walking into the Roque Santeiro market in Angola’s capital Luanda in 2007, she writes, she found herself beset with the same dilemmas she’d had about making photographs 20 years earlier.

Photography is far from a simple medium for Ractliffe; images aren’t transcripts of reality, and image-makers aren’t objective witnesses. “I used to go nuts with that stance,” she says. “It’s always about a position”. It’s an intriguing approach for a photographer who came of age in 1980s South Africa, an intensely political time and place.

““As a white, middle-class girl, I thought, ‘What do I know what it feels like to have your house bashed down and you and your family up-rooted and taken somewhere else? It felt really impertinent for me to be making those kinds of documents. I’m not saying that from a moral position. There was a necessary project in photography then. But I think there were people who were far better equipped to do it than me”

Born in Cape Town in 1961, Ractliffe grew up with Apartheid in full swing. Marriage or sexual relationships across racial lines was strictly outlawed, and Black South Africans were violently evicted from their homes. Ractliffe worked with local community organisations but found she couldn’t make the images that seemed to be needed. Equally, she couldn’t shoot photojournalism that directly engaged with the brutality.

“As a white, middle-class girl, I thought, ‘What do I know what it feels like to have your house bashed down and you and your family up-rooted and taken somewhere else?’” she says. “It felt really impertinent for me to be making those kinds of documents. I’m not saying that from a moral position at all, because I think there was a necessary project in photography then. But I think there were people who were far better equipped to do it than me. Also I’m shy, photographically, I’m not someone who can rush in.”

Instead she made quieter images, driving for miles up the West Coast in search of “a picture of nothing”, shooting stray dogs, or dead animals, or ramshackle buildings. In 1986 she photographed Crossroads, a series recording the views after bulldozers destroyed peoples’ homes. In 1988 she shot the Vissershok landfill, where people and animals scavenged for scraps.

A friend tagged her early photographs “blandscapes” but Ractliffe was undeterred (and is showing them in the exhibition). In 1987 she abandoned documentary, making a series of montages featuring dogs in apocalyptic though plausible surroundings. From 1990-95, she shot everyday scenes with a vintage Diana, a lo-fi, plastic camera. She included one of these photographs in the TPG show, a creepy view of a disembodied doll’s head, which she describes as “that dark image taken just before democracy”.

In 1996, Ractliffe began making N1 Incident/End of Time. Driving through the Karoo desert from Cape Town to Johannesburg, she attempted to take a photograph through the car windscreen every 100km. En route she found three donkeys shot dead by the roadside and, while having a look, heard a tyre blow out like a gunshot. She was so rattled she missed the next 100km marker. The resulting series suggests human frailty, and the impossibility of the so-called objective eye.

On 02 June 1999 she went to Vlakplaas, a farm west of Pretoria where the Apartheid government’s militia had once tortured and killed its opponents; her images of it testify to a failing, she says, to “the banality of the façade, the failure of that place to live up to the image it evoked in my imagination”. She drove round it taking photographs with a lo-fi Holga, and exhibits the shots as a single long strip.

When Ractliffe went to Angola in 2007, she felt compelled to do something more “straight”, a responsibility towards the people there. Even so, she avoided easy conclusions. Ractliffe’s work queries the idea of the decisive moment and even the single image; she’s interested in repetition – ditychs and triptychs – work in which each shot offers a slightly different view. She shows the world, but also the limitations of photography, and the sheer subjectivity of both her own work and her audience’s interpretations.

Her book includes a short story, an interview, and nearly 50 pages of essays and reviews. Each offers a different perspective, some close to her own interpretation, some very far from it. “Things were so binary [under Apartheid],” she observes. “It was literally black and white. I think I’m quite strong on the unfixedity of things, and maybe that’s partly a reaction.”

Jo Ractliffe is currently exhibiting her work as part of Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2022 at The Photographers’ Gallery in London.

Jo Ractliffe, Photographs 1980s-Now is co-published by Steidl and The Walther Collection.