Featured Image credit: Shadow Lives (2020-ongoing). © Nida Mehboob.

Currently on show at Dubai’s Ishara Art Foundation, Growing like a Tree charts the rise of artists and organisations across the region seeking real change

A thin pencil line connects a series of photographic clusters that form part of Growing Like a Tree, Sohrab Hura’s inaugural curatorial project, currently on show at Dubai’s Ishara Art Foundation. Visually, the show is like a diaristic splurge. Handwritten notes and small photos are tacked to the wall with masking tape. They crop up and reveal themselves through the framed works. They’re high up and low down, some near unreadable given their lofty heights. There’s a desk; there’s a long thin table; there’s a lot spewed out and on show.

The exhibition features the work of 14 artists and collectives from Bangladesh, Cambodia, Germany, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, and Singapore. Hura has, as far as is possible with an exhibition structure, evoked the layered and dynamic photographic worlds emanating from and around these regions.

There has been a “build up” of photographers, he says, explaining that the exhibition is an opportunity to present a freeze-frame of this moment, not movement. “[It presents] a temporary anchoring of flows that are continuous and will continue to be continuous.”

The show, fittingly dense, is made all the messier by a congested diagram Hura has drawn and pinned to the wall. It’s not so much a map of this network as a rhizomatic structure. There is no centre or focal point, but a seething mass of connections between individuals and collectives.

There is Indian photographer Dayanita Singh, for example, who is connected with the Thuma Collective, and Kaali Collective among other organisations. Then there’s the Nepal Picture Library and Raqs Media Collective, tethered by photographers including Jaisingh Nageswaran and Bunu Dhungana. And with lines leaping off the page and onto the gallery’s walls, we know these connections are not in any way conclusive.

So what has led to this growth of image-making in South and Southeast Asia? According to Hura, a “churning” has been occurring for several years. Politics in India has seen a turn to populist majoritarianism that thrives on divisive ideologies. The normalisation of extremism and the resulting tension across the region has increased the value and necessity of visual expression. Political agitation, Hura contends, has been felt “both at the individual and the state level”. Many photographers in this sprawling pool of talent articulate responses to the unrest around them.

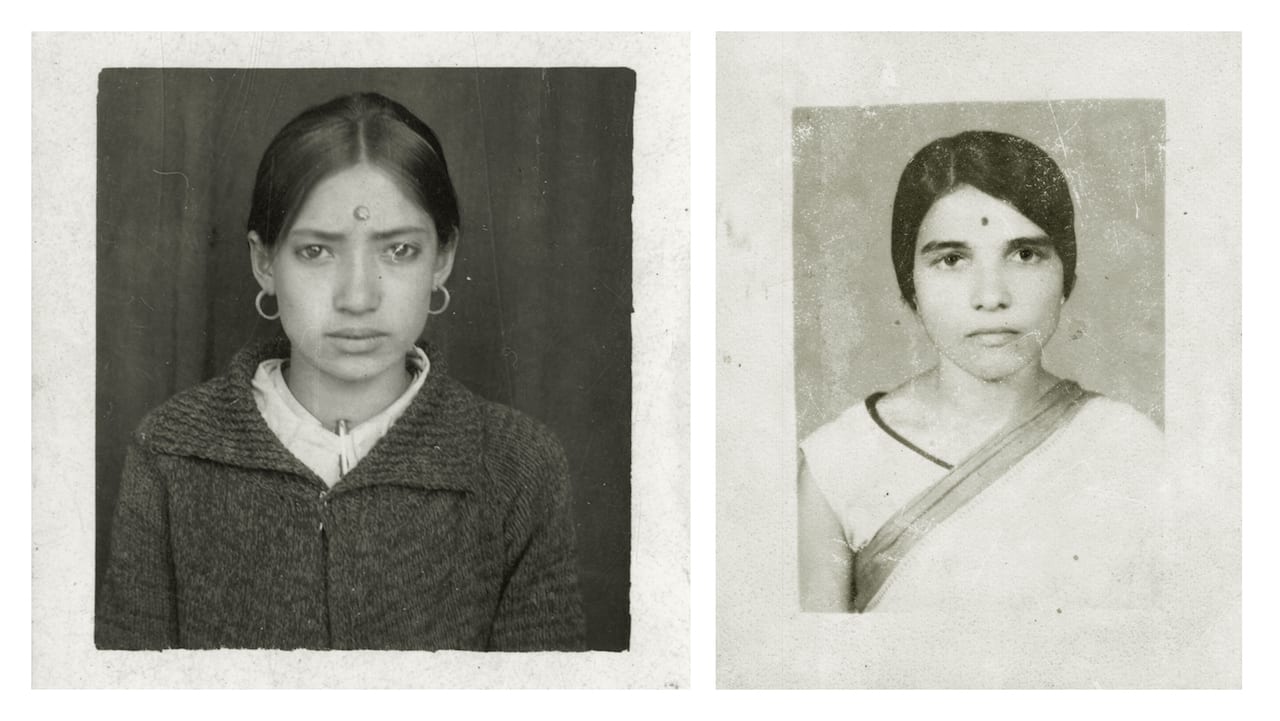

Jaisingh Nageswaran, for example, explores his own upbringing as a Dalit in the South Indian state Tamil Nadu. Dalits, formerly known as “untouchables”, are a community of people at the bottom of the rigid Hindu caste hierarchy, and have suffered public shaming for generations at the hands of upper-caste Hindus.

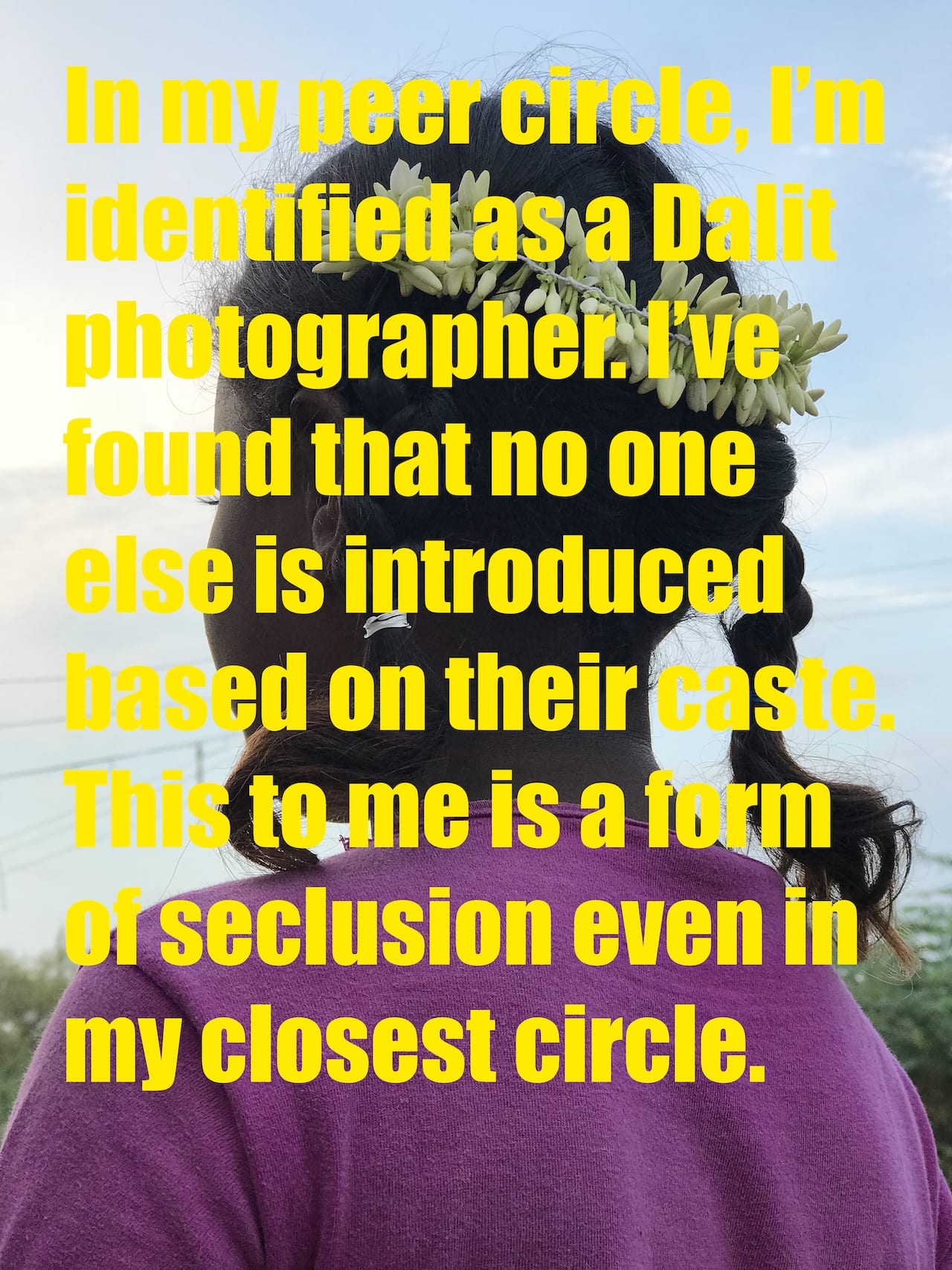

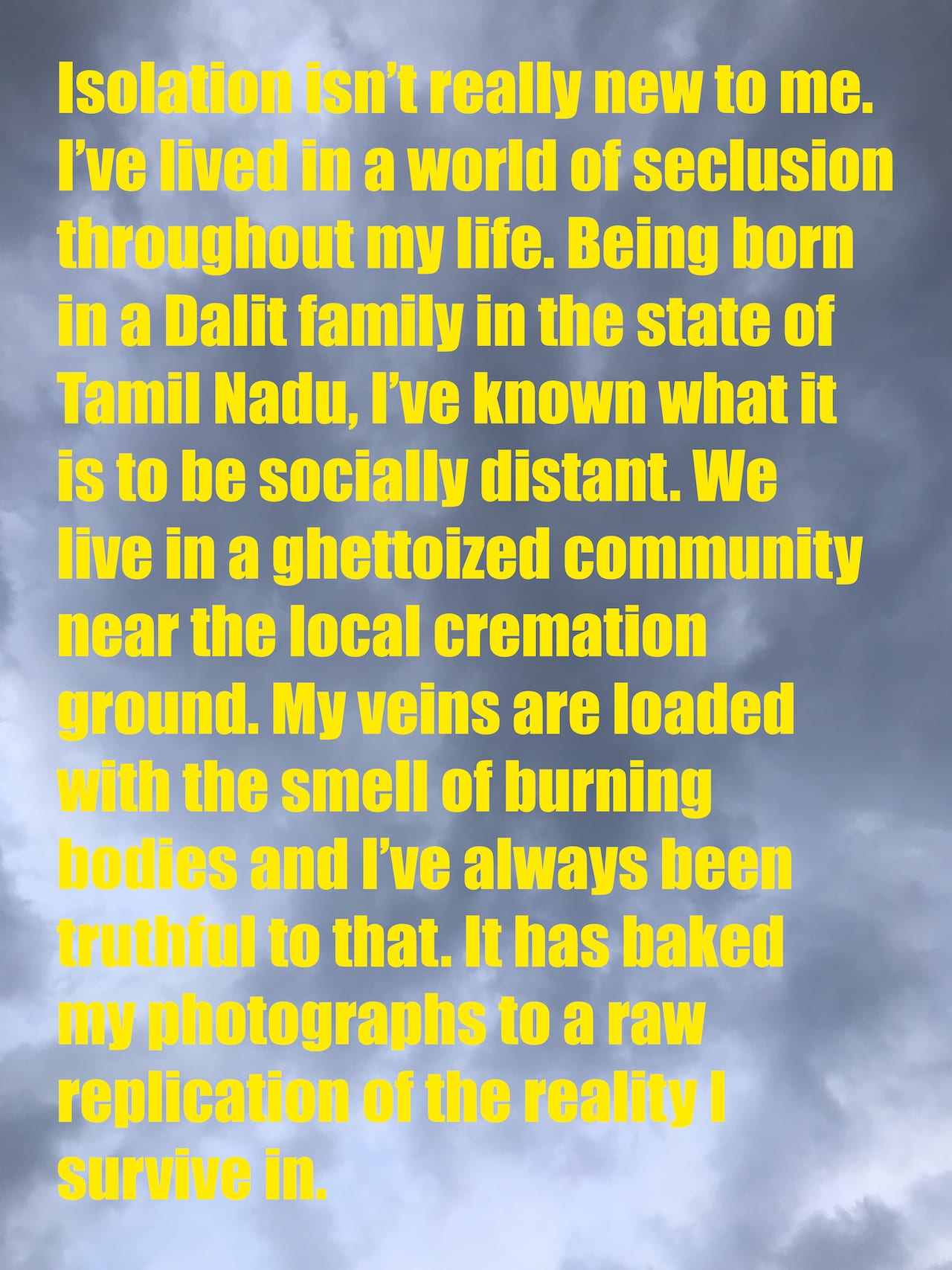

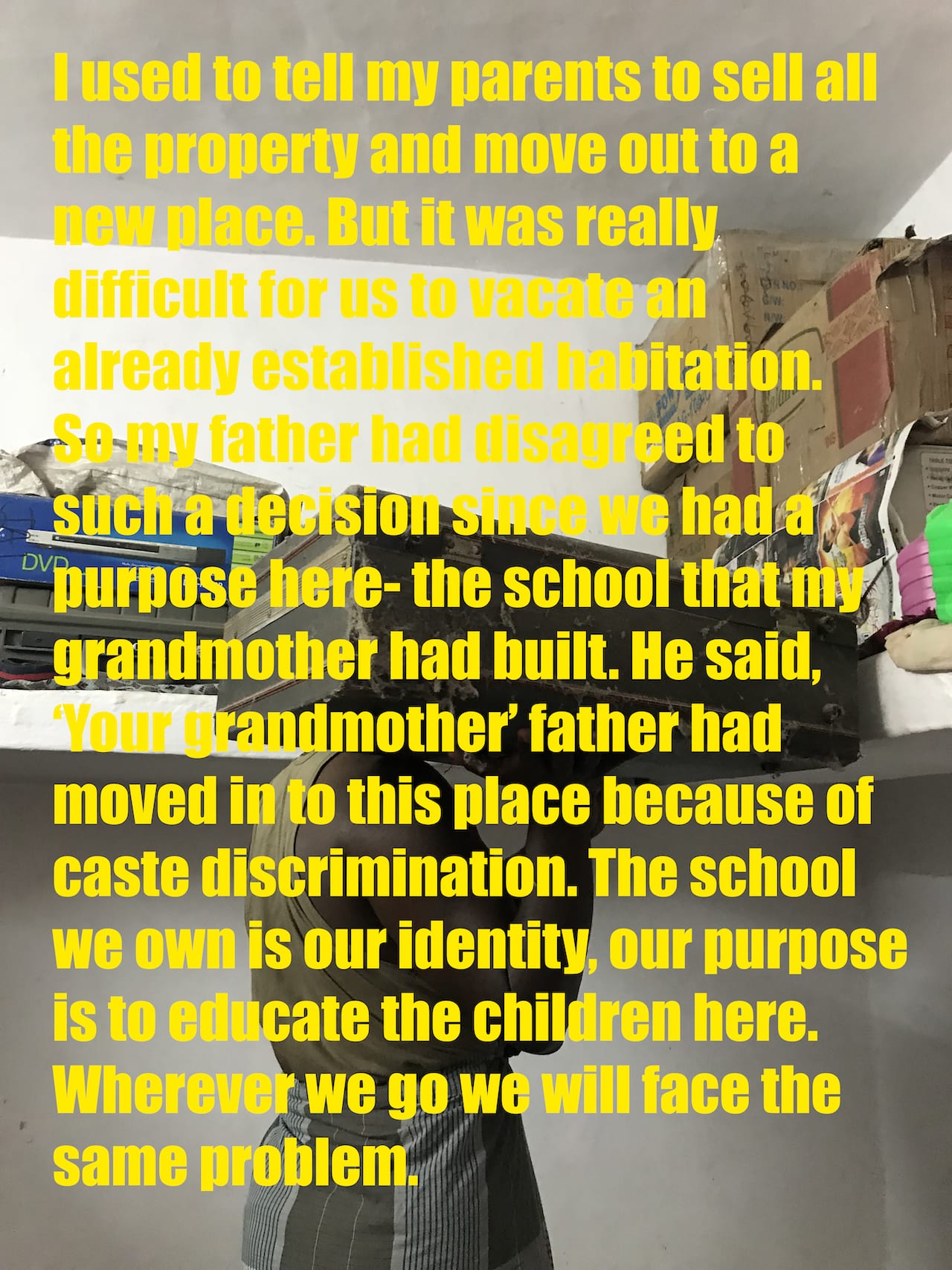

Titled I Feel Like a Fish, Jaisingh’s project is low-fi. Flattened to the wall like bill posters are a grid of six tender images of family life in southern India, overlaid with crude lettering. Thick yellow paragraphs accentuate Jaisingh’s poignant observations: “In my peer circle, I’m identified as a Dalit photographer. I’ve found that no-one else is introduced based on caste”; “We live in a ghettoised community near the local cremation ground. My veins are loaded with the smell of burning bodies and I’ve always been truthful to that.”

Jaisingh’s blunt words are there to speak of a broader India-wide discrimination experienced by this section of the population. His work seeks to expand the conversation about the terms of Dalit representation. “It’s usually been from outsider points of view”, Jaisingh notes. This tradition of visual framing and perspective, with all its burdens, has been a provocation.

“We don’t have documents about current Dalit community life”, he says. And in photography, there is even less representations of Dalit communities. Jaisingh sees himself playing a pioneering part in correcting this: “As a photographer, I felt I have to document my life.”

Over the past year, Jaisingh’s project has focused on the minutiae of his childhood village, Vadipatti. In 1953, his grandmother converted her home into a school for Dalit children. The school is now a permanent structure supported by the Government and Jaisingh is currently working on a film about its founding. The acclaim and acceptance received by the photographer has also given rise to an awareness of certain limitations.

“We need a support system”, he suggests, explaining that “being a community helps build us as photographers”. Jaisingh speaks emphatically about the connectivity facilitated by festivals in the region, such as Angkor Photo. Exhibiting at the Cambodian festival was a turning point: a place where he was able to meet editors and other photographers, and to engage in conversations and critiques.

For Nepali photographer Bunu Dhungana, it was Photo.Circle – the multi-limbed organisation behind international festival Photo Kathmandu, and digital photo archive Nepal Picture Library – that shaped her career. In a country without formal photography schools, Photo.Circle provides training, and initiates commissions and exhibitions.

The buzzy research centre and archive, where Dhungana now works, is a place of incessant discussion and debate, like a writers’ room wrangling over a script. There appears to be space for everyone at the table.

“There’s this incredible community of photographers now in Nepal”, Dhungana explains. “There are so many people; we bounce off our ideas and show our work across the region.” When asked about the utopianism of it all, she asserts: “When someone does something it’s for all of us in a way.”

Collaboration is the lifeblood of this burgeoning network of photo activism. The region’s geography of landlocked borders, despite antagonisms and barriers, allows for people, ideas and work to travel. Dhungana echoes what Hura illustrates in his spidery diagram: location is giving rise to a multiplicity of connections, and a raft of people weave in and out of each other’s practices.

This energetic tangle has in part come into existence as a result of the near non-existence of state funding and governmental support for photography. Collaboration, whether in formal collectives or otherwise, widens access to resources and, crucially, elevates the visibility of individual practices. For Hura, this is at the show’s core. “[It’s] not just about visibility for these people included in the show”, he says, but about helping “a young artist or photographer believe that it’s not one tree – it’s a larger forest with many”.

Growing like a Tree is on display at Ishara Art Foundation, Dubai, until 20 May 2021.