When approaching Mathieu Pernot’s 20-year work on a Roma family settled in southern France, you should leave all misconceptions and prejudices aside, as he did, and read the introduction to Les Gorgan, the photobook published by Editions Xavier Barral to accompany his critically-acclaimed exhibition at this year’s Rencontres d’Arles festival.

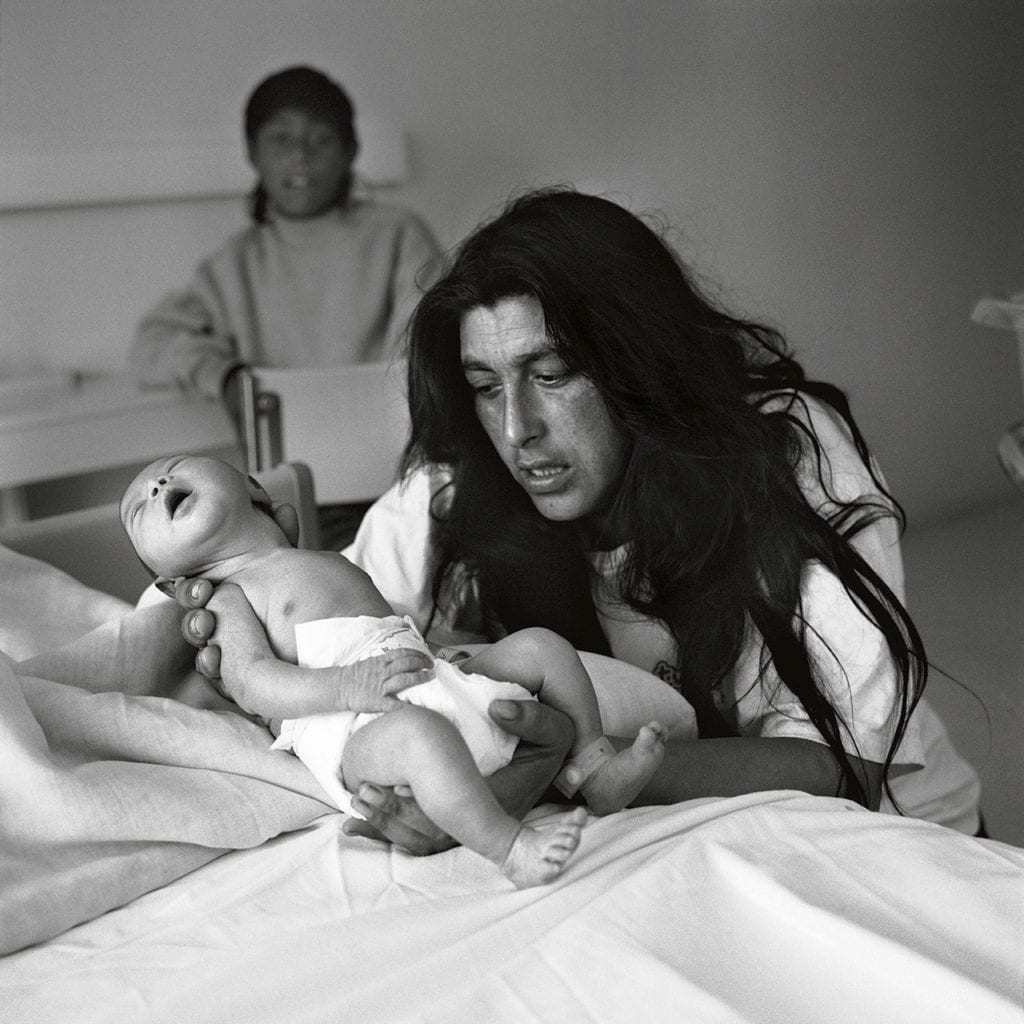

When he began, the French photographer writes, he didn’t know anything about the Gorgan family, nor was he aware that its members had been living in France for over a century. It was to be a transformative experience, one that led Pernot to witness the birth of a child for the first time, attend funerals and engage in a type of intimacy that only time and surrender can offer.

It is not often that you find an introduction written by a photographer that provides the reader with this degree of context – the key to interpretation – and sincere testimony. The project is about connection and from the outset he wants us to feel that same connection with his work and with the people he met. The book features an essay by Clément Chéroux, senior curator of photography at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, titled Piercing Eternity. Pernot, he writes, “quickly understood that a single look is not enough to grasp the complexity of the Roma culture, so he strived to multiply the points of view and different ways of looking”.

The photobook also carries a more anthropological text, Gorgangraphies by Johanne Lindskog, which begins by citing an entry from Pernot’s personal diary in 1996 in which the photographer notes: “I almost had to use the approach of an ethnologist faced with a dwindling population. But I don’t like to write and I lack the hindsight that analysis and research would provide. Maybe I am too emotionally attached to them.”

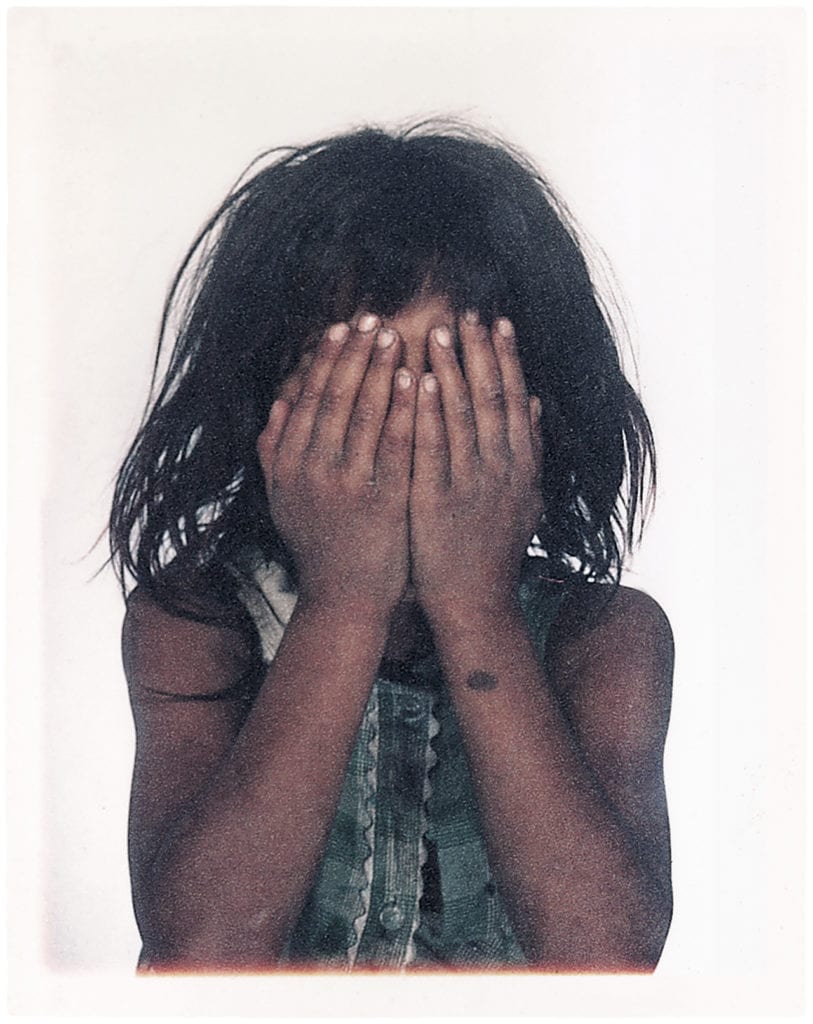

The Gorgan family, Arles, 1995 © Mathieu Pernot, courtesy Edition Xavier Barral/Eric Dupont gallery

His attachment to the Gorgan family had become an anthropological and historical enquiry of sorts, which would lead to his first exhibition in Arles in 1997, curated by Christian Caujolle, and his first book, Tsiganes, published by Actes Sud. The foremost recognition of his work would come in 2014 when he held a triple exhibition in Paris at the Jeu de Paume, the Eric Dupont gallery and the Maison Rouge.

In the catalogue of the Jeu de Paume show, The Crossing, curator Georges Didi-Huberman writes: You brought to the surface that photographic material – those documents on the barbarity – in order to give them a completely opposite use value, a value of reunion or recognition, and no longer of discrimination or indifference.” And therein lies the clue for interpreting Pernot’s work and understanding how it became a transformative experience. One that aims to transform the viewer also.

When he began, the French photographer writes, he didn’t know anything about the Gorgan family, nor was he aware that its members had been living in France for over a century. It was to be a transformative experience, one that led Pernot to witness the birth of a child for the first time, attend funerals and engage in a type of intimacy that only time and surrender can offer.

It is not often that you find an introduction written by a photographer that provides the reader with this degree of context – the key to interpretation – and sincere testimony. The project is about connection and from the outset he wants us to feel that same connection with his work and with the people he met. The book features an essay by Clément Chéroux, senior curator of photography at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, titled Piercing Eternity. Pernot, he writes, “quickly understood that a single look is not enough to grasp the complexity of the Roma culture, so he strived to multiply the points of view and different ways of looking”.

The photobook also carries a more anthropological text, Gorgangraphies by Johanne Lindskog, which begins by citing an entry from Pernot’s personal diary in 1996 in which the photographer notes: “I almost had to use the approach of an ethnologist faced with a dwindling population. But I don’t like to write and I lack the hindsight that analysis and research would provide. Maybe I am too emotionally attached to them.”

His attachment to the Gorgan family had become an anthropological and historical enquiry of sorts, which would lead to his first exhibition in Arles in 1997, curated by Christian Caujolle, and his first book, Tsiganes, published by Actes Sud. The foremost recognition of his work would come in 2014 when he held a triple exhibition in Paris at the Jeu de Paume, the Eric Dupont gallery and the Maison Rouge.

In the catalogue of the Jeu de Paume show, The Crossing, curator Georges Didi-Huberman writes: You brought to the surface that photographic material – those documents on the barbarity – in order to give them a completely opposite use value, a value of reunion or recognition, and no longer of discrimination or indifference.” And therein lies the clue for interpreting Pernot’s work and understanding how it became a transformative experience. One that aims to transform the viewer also.

“You need to learn to unlearn, to forget what you think you know and to let yourself be taken by things that, a priori, you wouldn’t understand or you wouldn’t imagine,” says Pernot, when we meet in Arles. “At the start of this project my approach was more theoretical, even cold. It then became a life experience.” And a life lesson too. “There are things that are more important than the photos you take and you have to let go and be carried away.”

Les Gorgan is not an angelic portrait of a Gipsy family or one that accentuates stereotypes or folklore. It doesn’t try to hide poverty or to beautify its subjects. Yet it conveys the beauty of the human being, the strength of family bond and the relentless fight to preserve freedoms. “I have always been fascinated by the fact that the Roma people have been in Europe for five centuries and they have always held their ground,” says Pernot. “They are the real first Europeans, the ones who knew no frontiers, who spoke many languages, who travelled to different parts of the continent”.

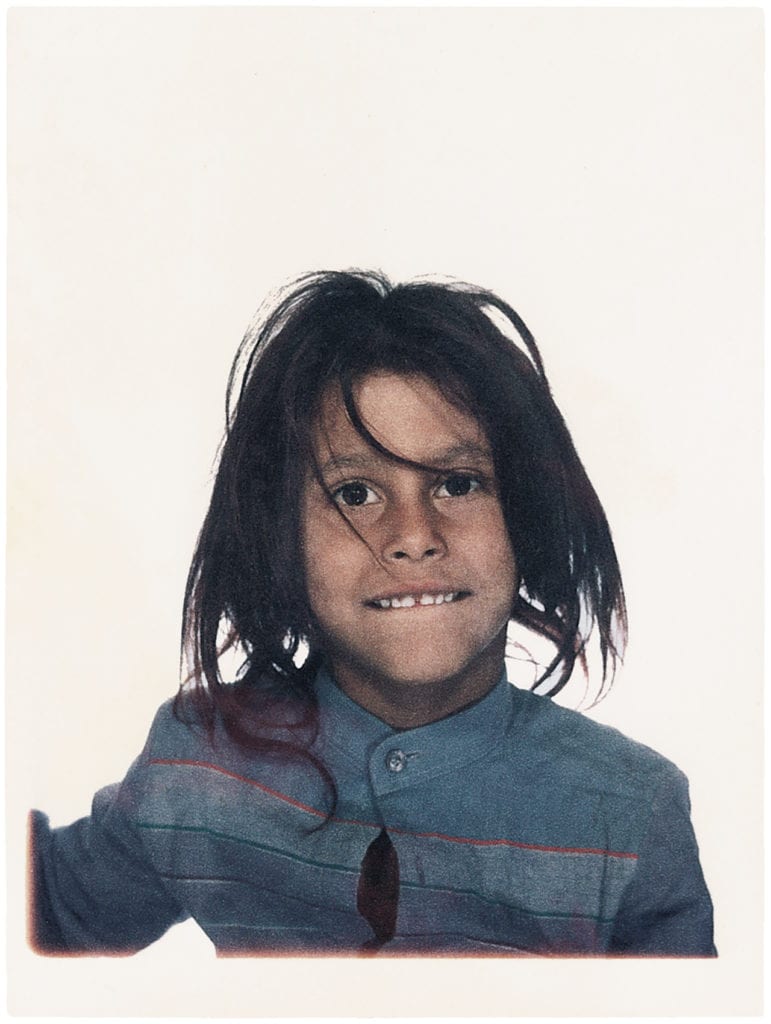

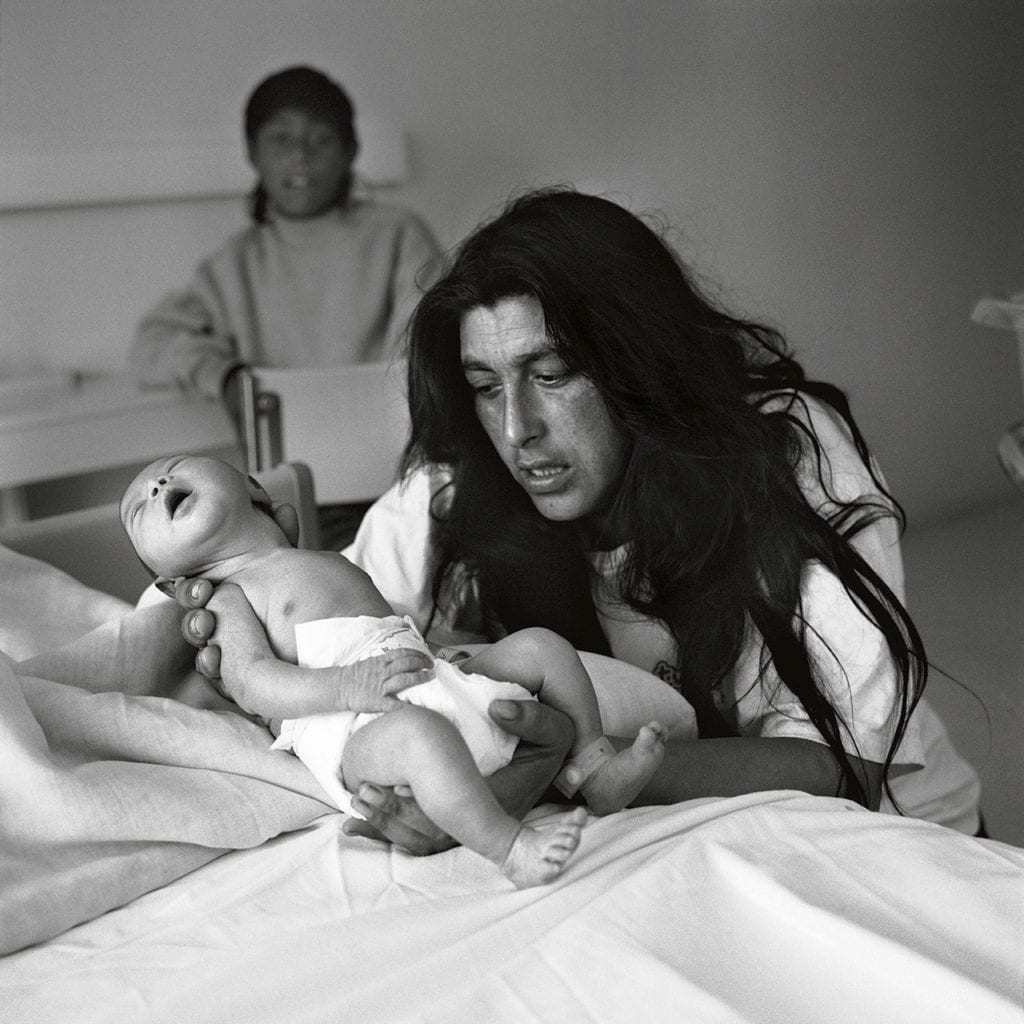

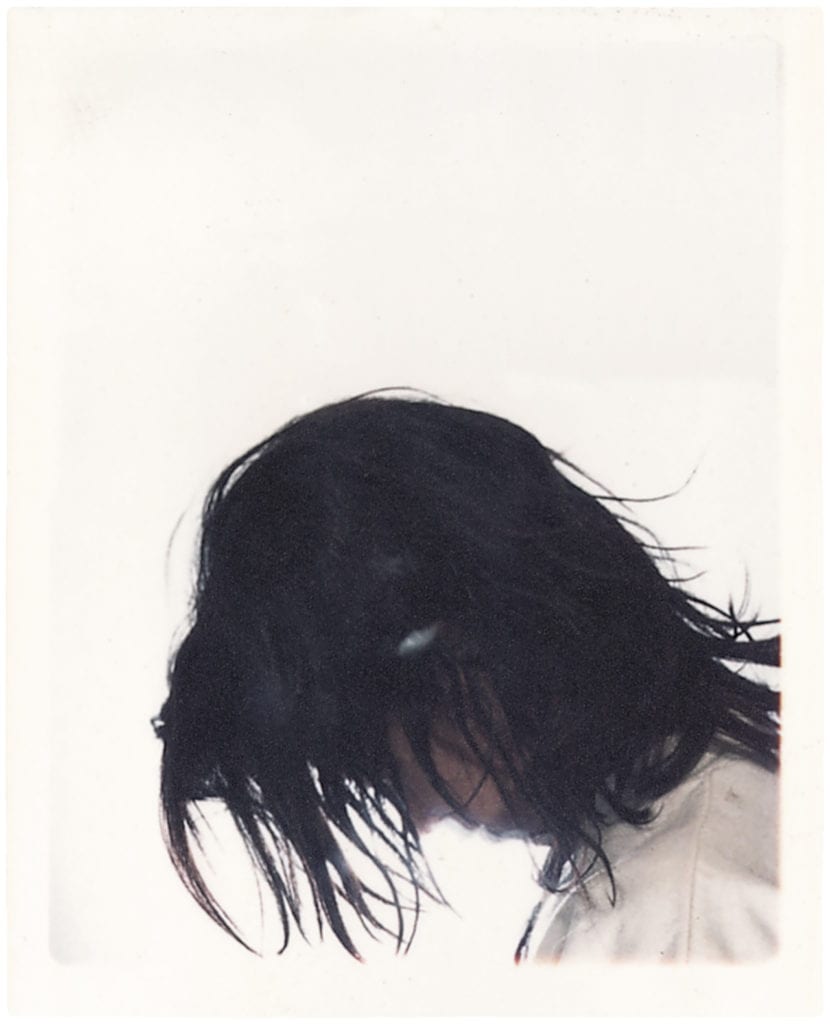

Ninaï © Mathieu Pernot, courtesy Edition Xavier Barral/Eric Dupont gallery

Pernot became so attached that his book includes both photos of the Gorgan family – in an intimate, joyful, reflective or celebratory mood – and of his own family, who established a special bond with his subjects. In his book, he says, “there is a double family album: there are the Gorgan but you can also see a picture of my wife [Spanish photographer Anna Malagrida] being blessed by Ninaï, as well as my daughter Anouk and my son Nicolas. My very own family became close to them too.”

Les Gorgan is not an angelic portrait of a Gipsy family or one that accentuates stereotypes or folklore. It doesn’t try to hide poverty or to beautify its subjects. Yet it conveys the beauty of the human being, the strength of family bond and the relentless fight to preserve freedoms. “I have always been fascinated by the fact that the Roma people have been in Europe for five centuries and they have always held their ground,” says Pernot. “They are the real first Europeans, the ones who knew no frontiers, who spoke many languages, who travelled to different parts of the continent”.

Pernot became so attached that his book includes both photos of the Gorgan family – in an intimate, joyful, reflective or celebratory mood – and of his own family, who established a special bond with his subjects. In his book, he says, “there is a double family album: there are the Gorgan but you can also see a picture of my wife [Spanish photographer Anna Malagrida] being blessed by Ninaï, as well as my daughter Anouk and my son Nicolas. My very own family became close to them too.”

For a period, when Pernot moved to Paris and began other projects, he stopped taking pictures of the Gorgan family. But when he returned, his ‘extended family’ gave him photographs they had taken themselves so that he could fill the gaps. They exchanged portraits and both sets of images became incorporated into Pernot’s ‘family album’. The gesture was returned when Pernot’s photographs were used as tomb decorations for Rocky Gorgan, one of the older brothers, who died in 2012.

Pernot says that, when portraying the Gorgan family members, he didn’t try to depict every single trait. “You try to capture this puissance de vie – the vivacity – and try to be as truthful as possible. You then make choices when editing the images.” Some things were off limits. “I took certain pictures of family members mourning the passing of Rocky,” Pernot recalls. “But his widow, who was full of tears, didn’t want those images to be included in the exhibition.”

Eric Dupont, Pernot’s gallery dealer in Paris, commends the photographer for challenging the tendency to oversimplify or fall back on clichés. He recalls how “three generations of the same family gathered around the artist for the opening of his Arles exhibition, along with friends, scholars, art collectors, politicians…”. It became evident, he says, that “this community, which lives sometimes on the fringe of our society, is actually part of our world – a world that many cannot or do not want to look in the eye”.

Just as Flemish photographer and artist Jan Yoors made The Gypsies (1967) as a “protest against oblivion”, Pernot is praised by Dupont for “putting the chronicle of this family in perspective and giving it a place in history, thus reminding us that nothing is fixed, that this ‘matter’ is very much alive”.

Xavier Barral, who published Pernot’s book, notes how the photographer has grown old with this family over the past 25 years or so. “Such a long-term engagement is so rare,” he says. And when it comes to representing members of the Roma community, he points out that “photography risks forgetting that they have a name – a last name – and that they belong to a family”. That, he says, is what Pernot has given back to the Gorgans: “Sharing his time with them and making us share their plight.”

Mathieu Pernot is signing copies of his book Les Gorgan at 3pm on 11 November at the Editions Xavier Barral stand at Paris Photo https://programme.parisphoto.com/en/book-signings.htm www.mathieupernot.com https://exb.fr/en/ This article was first published in the October issue of BJP, available via www.thebjpshop.com

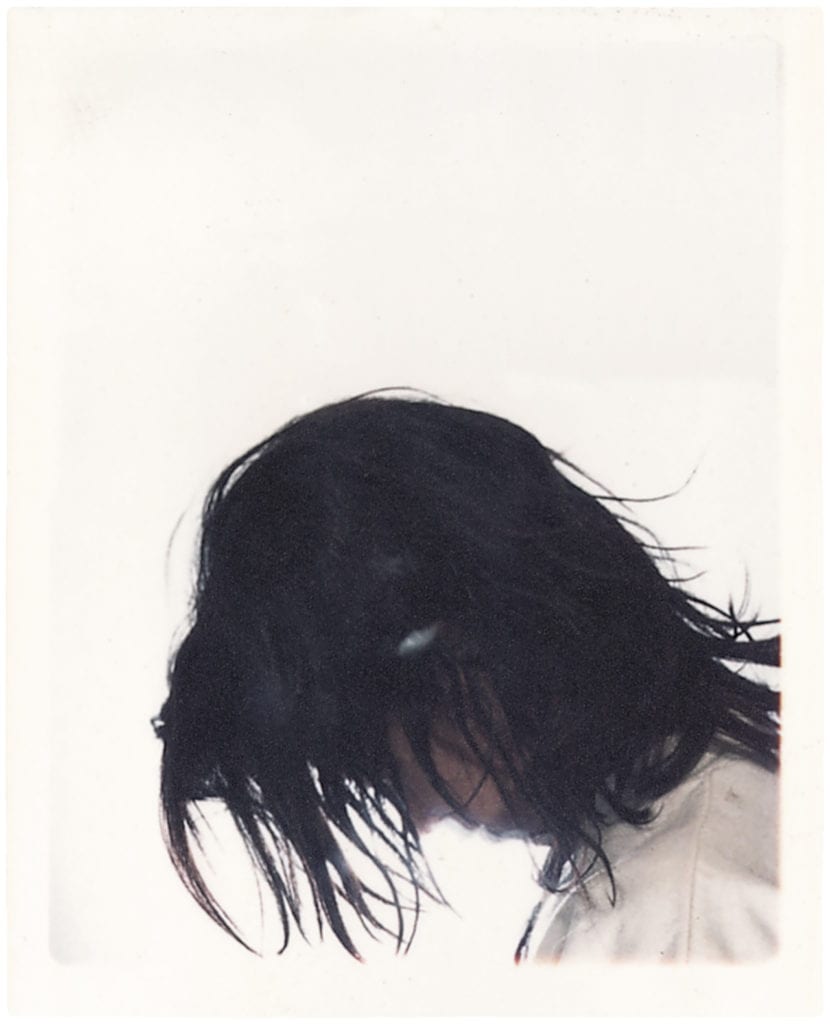

Johnny © Mathieu Pernot, courtesy Edition Xavier Barral/Eric Dupont gallery

Vanessa © Mathieu Pernot, courtesy Edition Xavier Barral/Eric Dupont gallery

Ninaï © Mathieu Pernot, courtesy Edition Xavier Barral/Eric Dupont gallery

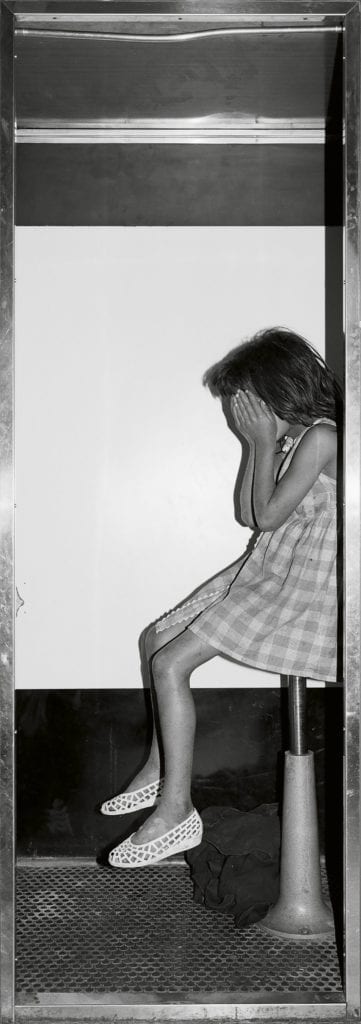

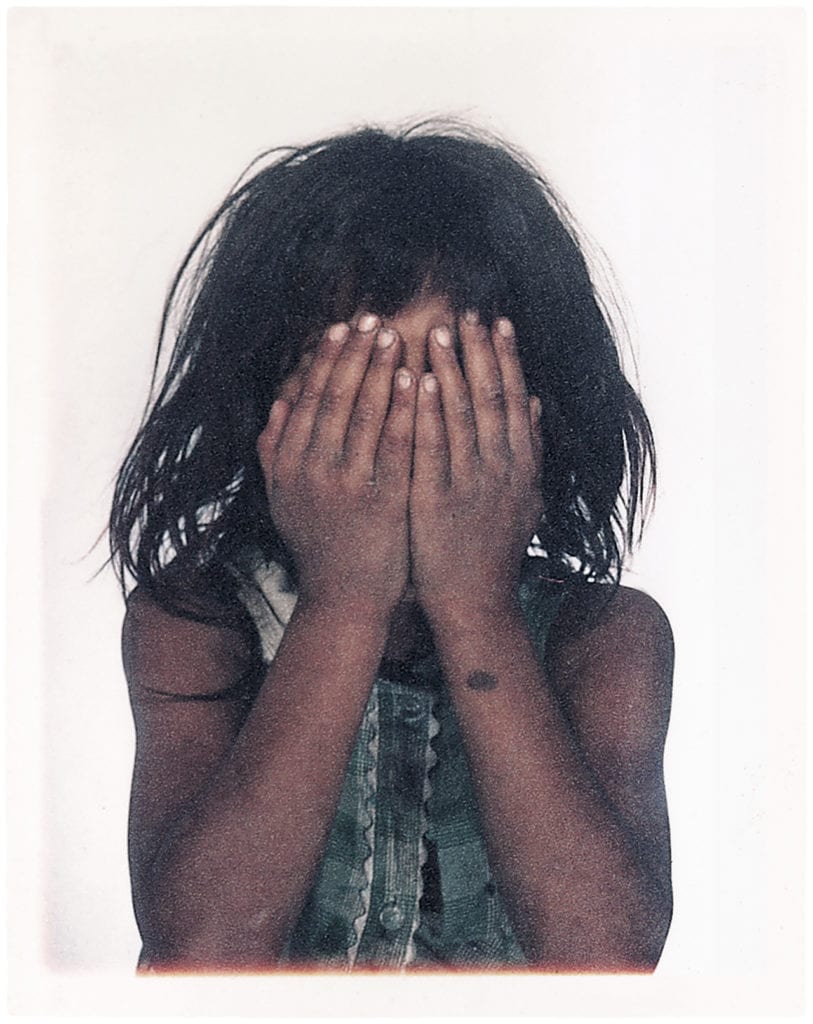

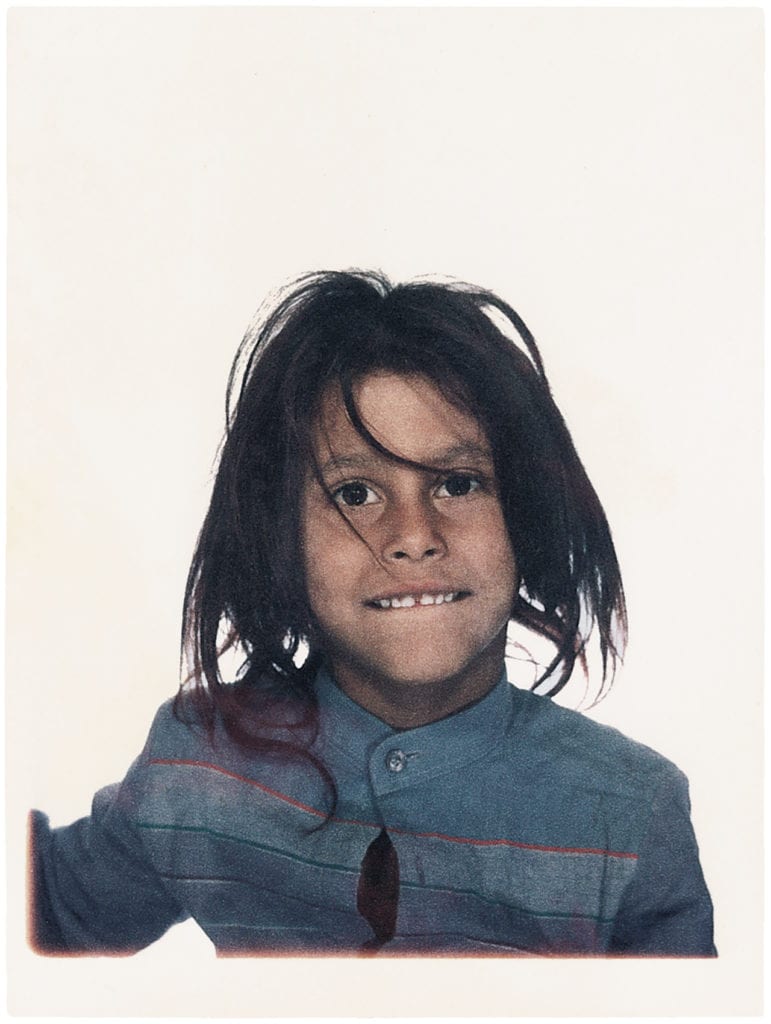

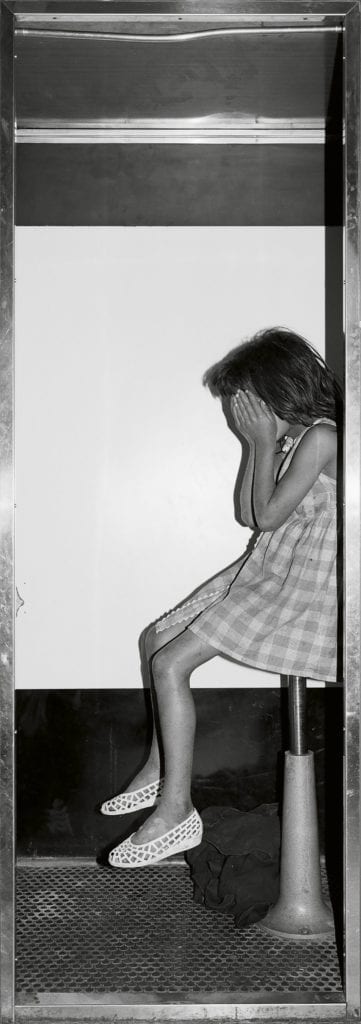

Priscilla, from the series Photomatons © Mathieu Pernot, courtesy Edition Xavier Barral/Eric Dupont gallery

Priscilla, from the series Photomatons © Mathieu Pernot, courtesy Edition Xavier Barral/Eric Dupont gallery

Priscilla, from the series Photomatons © Mathieu Pernot, courtesy Edition Xavier Barral/Eric Dupont gallery

Priscilla, from the series Photomatons © Mathieu Pernot, courtesy Edition Xavier Barral/Eric Dupont gallery

Pernot says that, when portraying the Gorgan family members, he didn’t try to depict every single trait. “You try to capture this puissance de vie – the vivacity – and try to be as truthful as possible. You then make choices when editing the images.” Some things were off limits. “I took certain pictures of family members mourning the passing of Rocky,” Pernot recalls. “But his widow, who was full of tears, didn’t want those images to be included in the exhibition.”

Eric Dupont, Pernot’s gallery dealer in Paris, commends the photographer for challenging the tendency to oversimplify or fall back on clichés. He recalls how “three generations of the same family gathered around the artist for the opening of his Arles exhibition, along with friends, scholars, art collectors, politicians…”. It became evident, he says, that “this community, which lives sometimes on the fringe of our society, is actually part of our world – a world that many cannot or do not want to look in the eye”.

Just as Flemish photographer and artist Jan Yoors made The Gypsies (1967) as a “protest against oblivion”, Pernot is praised by Dupont for “putting the chronicle of this family in perspective and giving it a place in history, thus reminding us that nothing is fixed, that this ‘matter’ is very much alive”.

Xavier Barral, who published Pernot’s book, notes how the photographer has grown old with this family over the past 25 years or so. “Such a long-term engagement is so rare,” he says. And when it comes to representing members of the Roma community, he points out that “photography risks forgetting that they have a name – a last name – and that they belong to a family”. That, he says, is what Pernot has given back to the Gorgans: “Sharing his time with them and making us share their plight.”

Mathieu Pernot is signing copies of his book Les Gorgan at 3pm on 11 November at the Editions Xavier Barral stand at Paris Photo https://programme.parisphoto.com/en/book-signings.htm www.mathieupernot.com https://exb.fr/en/ This article was first published in the October issue of BJP, available via www.thebjpshop.com