The last time we spoke to Vasantha Yogananthan he was preparing to release chapter one of his hugely ambitious seven-part project A Myth of Two Souls. A project that he started in 2013 with his first trip to India, the collection is a photographic re-imagining of one of the most significant Hindu texts, the epic poem Ramayana. Dating back to the 4th century, the Ramayana still holds tremendous significance in India, with its allegorical, mythical stories helping convey concepts such as love, duty, violence, loyalty and divinity.

Yogananthan had always been familiar with the Ramayana growing up – his Sri Lankan father told him stories from it during his youth in Grenoble, France, and he picked up comic book adaptations of it as a teenager. But it was only when he visited India that he realised just how interwoven the analogies presented in Ramayana are with the experience of everyday life on the subcontinent, and just how thin the line can be between mythology and reality.

This realisation formed the foundation of A Myth of Two Souls, a re-telling that carefully blends atmospheric landscape, portrait and documentary photography with reinterpretations of the text by various female Indian writers. Now onto its third chapter, Exile, Yogananthan is determined to keep audiences invested and intrigued, each chapter offering something new and visually rooted in the allegorical nature of its subject matter.

Since 2013, Yogananthan has travelled to India twice a year to capture the landscape and people; I caught up with him two days before his second trip of 2017, to learn more about Exile and about how he’s continuing to learn from this huge project as he approaches its half-way point.

Ramayana tells the story of Prince Rama and his epic journey through India to rescue his wife Sita from the demon Ravana. Yogananthan’s retelling of chapters one and two, Early Time and The Promise were quite introductory, he says, with lengthier, more literal texts telling the stories of Rama and Sita’s youth, and their subsequent marriage, respectively. Chapter three, on the other hand, spans over a much longer period of time and follows Rama as he is banished from the Kingdom to live in the wilderness, accompanied by Sita and his brother Lakshmana. This enabled Yogananthan to be more metaphorical with the presentation, and led to a visually darker, more dreamlike presentation of the story.

“For chapter three we decided to build a narrative that is much more metaphorical and with very little text,” he explains. “It leaves more space for the readers’ imagination. Nothing much actually happens in chapter three: they just walk and walk further into the Indian wilderness. We wanted to the reader to feel the same way they would, like they were walking with them. In the pictures there is a lot of fog and the landscape constantly disappears and reappears again. It creates the idea of leaving the city and getting lost in the wilderness.”

This idea is emphasised in the book’s design: its printing on deckle-edge paper gives it simultaneous sense of lightness and weight, the appearance of small photos in the middle of large white pages “give the feeling of a long time passing”. As the reader delves deeper into the book the sense of distance and of isolation becomes greater and greater, like we are venturing with Rama further into banishment.

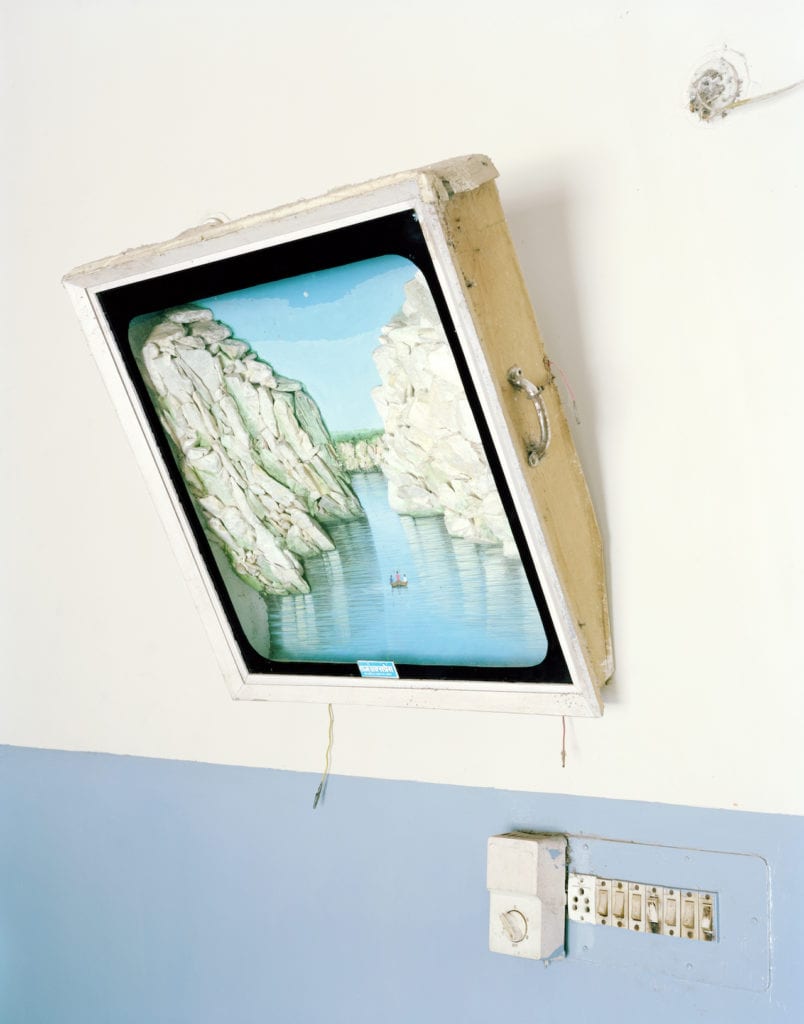

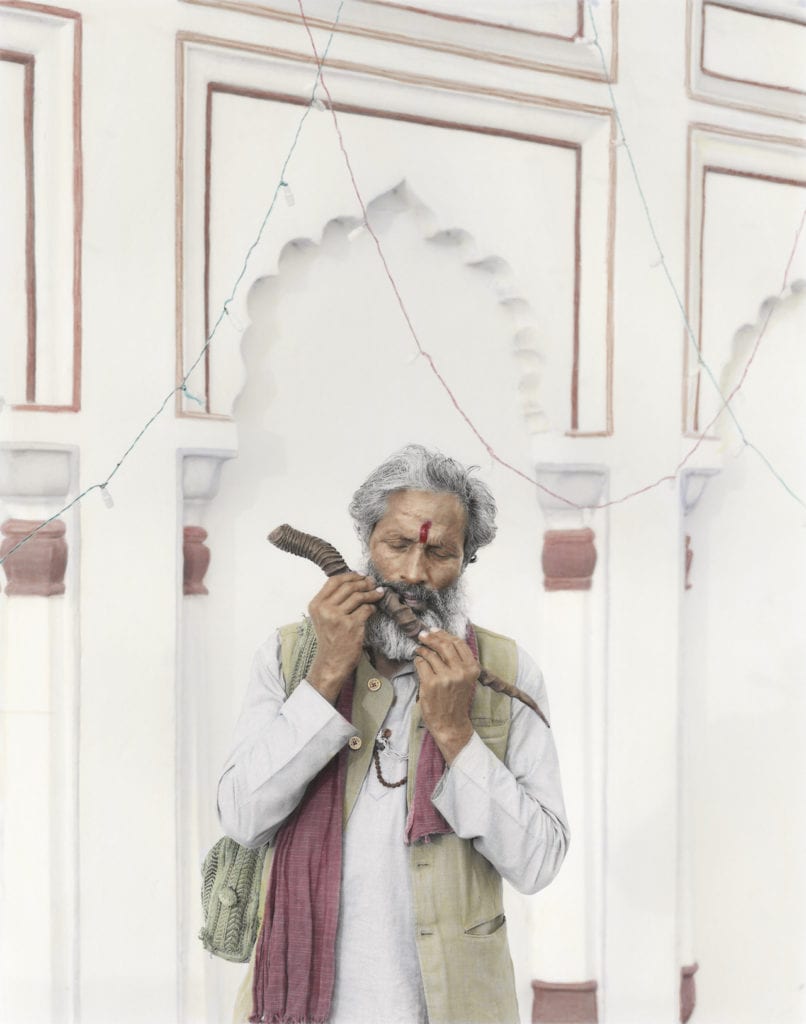

In Early Times and The Promise Yogananthan made great use of hand-tinting, capturing a black-and-white images and having them painted by a local artist trained in meticulous colourising. The result was an opalescent palette, and an often bright, luminous atmosphere. By contrast, Exile features far fewer hand-painted photographs, the handful that are present painted by Jaykumar Shanker. Every shot is captured on analogue using a large-format camera with a generous use of over-exposure; in using the landscape and images shot primarily in winter, Yogananthan has created an obscure and hazy atmosphere.

“At the beginning of the book you have this very quiet and foggy landscape and then all of a sudden you switch into the night and you get pictures that are more bizarre,” he says.

On his travels Yogananthan has retraced the steps that Rama takes throughout Ramayana – a trajectory that has seen him moving off the beaten track of India’s largest cities and toward ancient sites like Janakpur in Nepal and Ayodhya, as well as towards more rural communities such as Avani in the state of Karnataka, and Buxar in Bihar. A considerable chunk of Exile was shot in the city of Allahabad, and in surrounding communities in the state of Uttar Pradesh.

“It is from there that the heroes cross the Ganga,” Yogananthan explains. “It’s the crossing from civilisation into the jungle, into the wilderness. The crossing of the river metaphorically shows that they are not safe anymore. I spent a lot of weeks in Allahabad shooting very early in the morning. It was winter, which is why there was so much fog. The fogginess was used to evoke that crossing, that passage into the unknown. Exile is where the drama starts and from where all the events will unfold in the next chapters. In that sense it symbolises the first steps into the darkness.”

Unlike the previous two chapters, the portraits in Exile are taken from a considerable distance, showing their characters as isolated figures, lost in unfamiliar land. One of the only exceptions is the close up portrait of a woman in a blue sari, gazing longingly off-camera. “It depicts the mother of Rama learning that her husband has passed away,” Yogananthan explains. “It is the only one that appears in the book because it signifies the first death in the family. After that image the text reads: ‘Dear father, your body returns to the five elements of which it is made – earth, fire, water, air and ether’.”

Using the people he met on his travels as models, Yogananthan creates a sense of narrative throughout the book, which contains brief texts by Arshia Sattar. The second to last image in the book is of an old man playing a bansuri (an Indian flute made from bamboo), for example; he is said to represent the story’s antagonist Ravana, though there is no overt indication of that in the book. In doing this, Yogananthan hopes to create a sense of suspense and anticipation in his work.

“In chapter four, which is the chapter where Sita will be abducted, the abduction happens during a hunt. So the end of the chapter three you see a picture of the deer that Rama is going to enter the forest to hunt. It’s a way of linking the end of chapter three to the start of the next one. The last bit of text in Exile reads: ‘I swear to you they will suffer for love. Your nation will be avenged’. It’s a climax to make the readers want to know what happens next.”

Arshia Sattar’s text in Exile is sparse and poetic, and at times placed directly in front of the corresponding images. The objective, according to Yogananthan, is to create a metaphorical and symbolic interplay between the text and images, allowing for the narrative to reveal itself at the discretion of the individual reader’s imagination. Describing working with Sattar as much more of a dialogue than a commission, Yogananthan explains how crucial her input was.

“She interpreted the pictures and read things in them that I wasn’t even thinking about,” he says. “There was a lot of back and forth. In the previous books people thought I shot the pictures after having read her text but it’s actually the opposite. The pictures and the text just end up happening to be related in a more metaphorical way.”

He also believes that it was a form of “political statement” to use female writers for each chapter, Sattar writing for The Promise and Exile and Anjali Raghbeer providing the words for Early Times. For Yogananthan it was crucial that the female characters of Ramayana be well respected and represented as key parts of the narrative. “A man would have obviously written it differently,” he says. “He couldn’t think as Sita would think.”

The portrayal of the Ramayana’s characters is one of the most important parts of A Myth of Two Souls as far as Yogananthan is concerned, especially given the text’s lingering influence on the Indian cultural and social psyche. He uses the climax of chapter three as an example of this, detailing the scene in which Rama and Lakshmana cut off the nose of Ravana’s sister Shurpanakha after she propositions them and attacks Sita.

“It’s an act of pure violence,” Yogananthan says. “It’s the first time that you see that these people aren’t just ‘good guys’, that they have a dark side. And I think that’s one of the most interesting points of the Ramayana. The characters are not black and white, they are all grey. This act seals the fate of Sita and pretty much leads to every other event in the upcoming chapters.”

He continues by describing the link between this part of the story and the ways in which the people he met explained its relevance in contemporary India. “A lot of people still believe that every act you undertake seals your fate in some way or changes your destiny,” he says. “Everything that you do will have consequences in the future.”

Yogananthan remains deeply committed to this project, which he has also published through the company he runs alongside his partner Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi, Chose Commune. With each trip his understanding and appreciation of the Ramayana grows, he says, and with each chapter, new technical and thematic challenges are met and embraced. With plans already underway for chapter four, I leave Yogananthan in high spirits as he embarks to the east of India for the autumn.

“I’ve travelled the world and seen so many countries but it has only been in India that I have seen that blurry line between mythology and real life,” he says, with a hint of awe in his voice. “It changes me every time I go there.”

Vasantha Yogananthan is signing copies of Exile at 2pm on 11 November at Polycopies https://www.polycopies.net/index.php/project/book-signings/ Exile by Vasantha Yogananthan is published by Chose Commune (priced €45). www.chosecommune.com www.vasantha.fr BJP published an interview with Yogananthan on chapter one of his project, Early Times, earlier this year www.1854.photography Vasantha Yogananthan’s work is currently on show at the Science Museum in the group show Illuminating India www.sciencemuseum.org.uk