I have to use a little imagination when stepping into the space that is home to Martin Parr’s eponymous foundation one early September morning. But that is to be expected, since it is still largely a construction site – albeit a very nice one. Builders wander nonchalantly past, boxes of books and prints are stacked here and there and nothing is quite where it should be.

Despite their relatively calm demeanours, it is obvious that the photographer and his team are itching for the work here to be completed so that they can put the finishing touches to the Martin Parr Foundation ahead of its grand opening this autumn.

You enter into a good-sized space tucked away in a quiet corner of Paintworks, a fashionable live-work factory conversion in south-east Bristol that’s home to more than 50 businesses. Other residents include media and technology companies, artists’ studios, marketing and creative agencies, a bookshop and a dentist.

This space will be the gallery, Parr tells me, where three or four exhibitions will be held each year, as well as staging talks and screenings. As we move on, the layout becomes cosier, divided up into smaller areas that contain many tall cupboards and shelves where Parr’s print archive and his collection of British and Irish photography will be kept.

“Every print I’ve ever been interested in doing is in those grey boxes. There must be half to three-quarters of a million prints in that lot,” he says, directing my attention to a wall of storage crammed with boxes of 10×8 prints. “We print out everything digitally. We’re very efficient in terms of archiving.”

He shows me a stack of colour inkjets, which he is currently working on. “This is from the past two weeks, shot at Notting Hill Carnival. I edit from the prints. These will then go into the archive. I’ll probably run out of space soon. Don’t tell anyone that, though,” he adds with a laugh.

The prolific photographer cum-curator is now known for his collecting almost as much as his own work, encompassing everything from Soviet space-dog memorabilia and Saddam Hussein watches to exhibition prints and book dummies made by key figures of postwar documentary photography – from Britain and beyond. And the 335sqm space he bought earlier this year is designed to bring this collection to public view.

Building work began in March and Parr and his team – including the foundation’s director Jenni Smith, who has worked for him for more than 10 years, Louis Little, who does the printing in house among other things, and assistants Charlotte King and Nathan Vidler – have been in the space since the summer. “I’d been looking for 18 months for a suitable building and this came up,” says Parr, who has lived in Bristol for 30 years.

He proudly points out key features as he shows me around the new-build property, which he bought for £600,000. “There will be a shop by the main door and everything from here on will be temperature controlled. Here are our plan chests; this will be the negative cupboard; this is the server; and the floor we put in.”

“It’s a good location, near the centre and is a developing site,” he says in his characteristically direct and efficient way. When I ask what the cost has been to set up and kit out the units, he is a little more vague. There is a fancy wine fridge and under-floor heating facilitated by two kilometres of pipes, he tells me enthusiastically. So while it’s not quite a case of no expense spared, it is clear that Parr has been keen to do things properly, having spent a great deal of time preparing for this moment.

“I’ve saved, over the past five years, a substantial sum of money in order to facilitate this,” he says. “Obviously there is a limit to what you can buy so you have to go slowly and work out what you think is important, how to get hold of it,” he says. “There are many avenues I’m pursuing, which I’m reluctant to name because they’re still being pursued [in terms of] funding, and then the purchasing of work.”

Although Parr won’t talk numbers throughout our conversation, the foundation has been at least partly funded by the recent ‘sale’ of his 12,000-strong collection of photobooks. It was, in fact, partly acquired and partly gifted to Tate with support from Maja Hoffmann’s Luma Foundation and The Art Fund, among others. The foundation is looking for additional funding to supplement what Parr is putting in but, he acknowledges, “The main source of income will be me.”

He hasn’t kept any books back after the Tate gift-acquisition but he is replicating the British and Irish books from the collection. Does he intend to keep collecting books? “Not with the same relish that I have before but, for example, I recently bought a collection of Indonesian books and I hadn’t realised how alive Indonesia is photographically. I’m curious to see what is going on.” He and Tate have a “loose agreement” that he will continue to supply and suggest books, says Parr, but nothing formal has been agreed.

Officially founded in 2014, the Martin Parr Foundation will not only house Parr’s own archive but also his vast collection of prints and dummies made by other photographers. They’re mainly British or Irish but there are works by several photographers from abroad who have photographed in the UK. “Did you see the Strange and Familiar show I curated at the Barbican? I’ve purchased some of that. I’ve just bought the Gilles Peress selection, and Bruce Gilden. Most of the Sergio Larrains I owned anyway.”

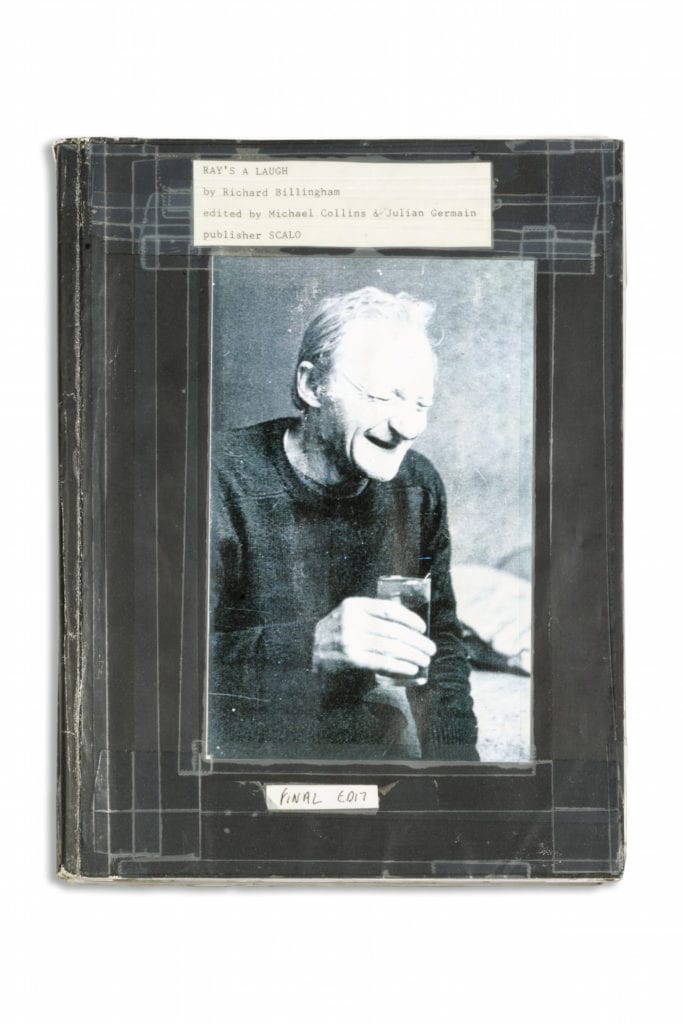

“I have a lot of Chris Killip works and a lot of vintage Tony Ray-Jones. I like dummies. I buy them from the photographer. Here’s the Ray’s a Laugh dummy [made by Richard Billingham, and eventually published by Scalo in 2000].” I remark that I feel I’m holding a piece of history, to which Parr replies, “Well, you are!”

I’m interested to know whether he tends to purchase prints that he likes or tries to be strategic in what he buys. It’s both, he says, adding that he collects work he feels is important. “First, I suppose, I’m giving priority to things I think have perhaps been overlooked by other national collections. Obviously I’m not trying to be in competition with the V&A. But when I collect, I collect in depth. I buy a lot. So I’ve got prints from Tom Wood’s All Zones Off Peak.”

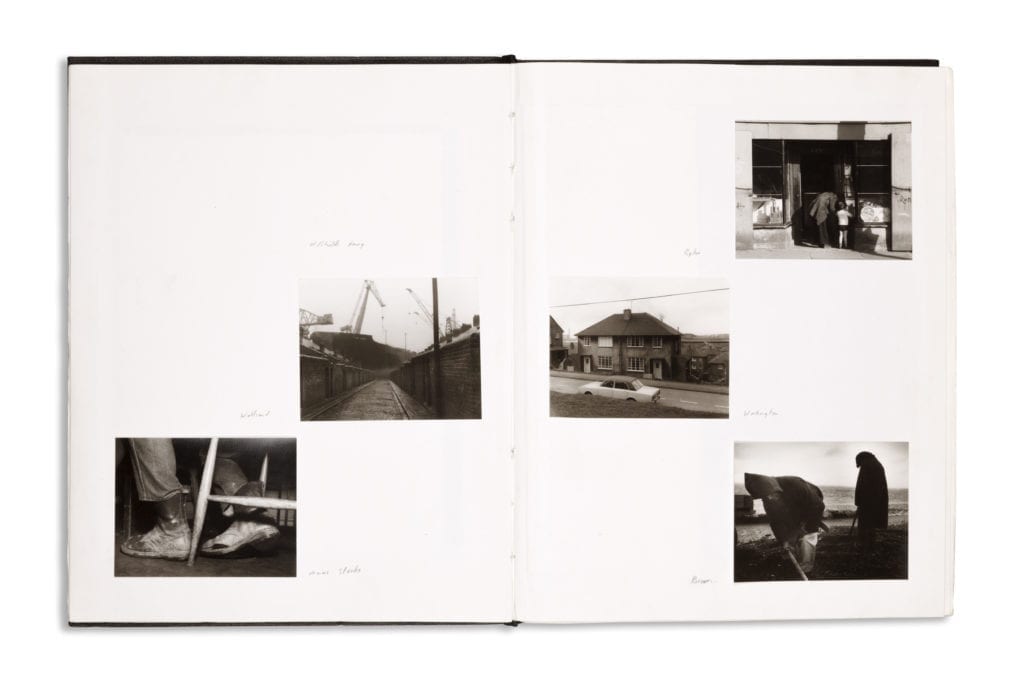

He also has the dummy of this project, which he passes across. “This is the only one,” he notes, before continuing. “I support people by buying the work and putting it in the collection. I’ve recently bought some pictures from John Myers, who I think is another underestimated photographer.

At 65, then, Parr is ahead of the curve in thinking how he might preserve his own legacy in ways that many other photographers have not. He is clearly as shrewd a businessman as ever but he plays down what he is doing in his typical matter-of-fact way. “It’s just something I thought about,” he says, when I ask why he wanted to set up the foundation.

“Having this big collection and wanting to get a space to house it and also exhibit it, a foundation seemed the logical thing to do. Obviously I won’t last forever. The idea is that when I drop dead, hopefully I’ll have set it up in such a way that it’ll be sustainable. That is a big ask but that’s the plan.”

The space will be open Wednesdays to Saturdays and visitors will have access to a bespoke digital catalogue detailing everything in the collection. “For example, with Killip we will have over 1000 pictures digitised, which people will be able to see here,” says Parr.

“So if anyone is researching Killip, this will be the place to come. They will have access to the dummies of In Flagrante, and I’ve got the collection of Chris Killips he made for Rencontres d’Arles in 2004. There are no other ones in any other public collection anywhere in the world.”

The collection is unique in many ways, I comment, as Parr continues to name items of which he is clearly especially proud. “I’ve just bought the dummy of Gilles Peress’s Northern Irish work, which is, along with In Flagrante, probably the two greatest books about Britain in the past 50 years.”

Why is it so important to him to collect British photography? “Because I think British photography is still under-appreciated,” he says, prompting me to ask by who? “The art establishment. Even within Tate. Photography is loved by Tate Modern but less so by Tate Britain.

“Until Don McCullin has his one-person show at Tate Britain in 2019, they will never have done a proper show of a British photographer even though they’ve been actively saying they’ve embraced photography since 2002.”

Parr’s views on the treatment of British photography within British institutions are clearly deeply held and, while the foundation can’t compete with the big institutions – “I’m not pretending to” – perhaps he and his team can be more nimble and reactive, and produce shows that are more intimate. “Visitors will see good work,” says Parr. “It may not all be British but it’s more likely to be. And hopefully it’ll be things they won’t have seen before.”

Is he keen to look back at the canon of British documentary photography or to show contemporary works? “Well, both. I want to do all kinds of things. I have this massive collection so I can at any point show highlights from that. We want to be flexible. I don’t want to book up years ahead because if I see something I really like I can just put it on.”

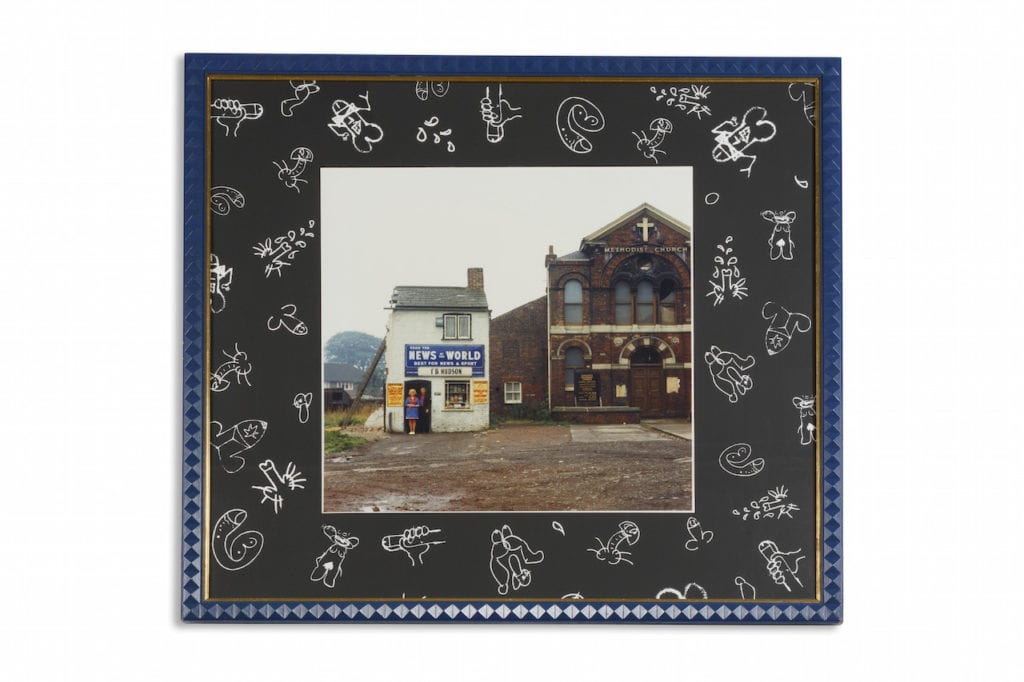

The first few exhibitions at the foundation have, however, already been decided. First up will be Parr’s Black Country Stories, a commission from West Midlands-based arts organisation Multistory. Then there will be work by Scottish photographer Niall McDiarmid, followed by David Hurn’s Swaps in early 2018, which Parr previously curated for this year’s Photo London. The exhibition will present prints from Hurn’s collection, built up over many decades by swapping prints with other photographers.

“I recognise I have some taste-making ability and a platform to share the things I think are underestimated and overlooked,” says Parr when I ask if and why he enjoys curating other people’s work. “In the next five to 10 years there is a lot more activity planned around books but I have to be careful about not giving too much away when it hasn’t happened.”

It sounds like you will never stop looking and researching, I suggest. “No, no,” he replies. “I mean, you look and you find and it’s exciting. People send me stuff and I get a lot of bad work sent to me but then, occasionally, you get work that is really [good]. I’m constantly looking for new, interesting photographers.”

How have his tastes changed over the years in terms of what he wants to collect? “Good work is good work, which I’m always interested in – work that I think will survive and that works. That nails it. It’s very difficult to define that, really.

“I’ve been very lucky. I have secured a very good living from doing this, and so the foundation is a great way to feed some of that back into the system.”

martinparrfoundation.com The foundation is set to open on 25 October 2017. This is a shortened version of an interview with Martin Parr which will be published in BJP’s November edition www.thebjpshop.com