“The working class get it in the neck basically, they’re the bottom of the pile,” says Chris Killip. “I wanted to record people’s lives because I valued them. I wanted them to be remembered. If you take a photograph of someone they are immortalised, they’re there forever. For me that was important, that you’re acknowledging people’s lives, and also contextualising people’s lives.”

We’re discussing his work in England’s North East from 1973-1985, images from which made up his seminal photobook In Flagrante. Released in 1988 and showing communities reeling from the effects of de-industrialisation, it was immediately hailed as a classic – and read as a statement against Margaret Thatcher, the Prime Minister most identified with the process of de-industrialisation. In fact Killip has long been at pains to reject that reading, pointing out in In Flagrante Two, published in 2016, that he actually shot his images under four Prime Ministers, “Edward Heath, Conservative (1970-1974), Harold Wilson, Labour (1974-1976), James Callaghan, Labour (1976-1979), Margaret Thatcher, Conservative (1979-1990)”.

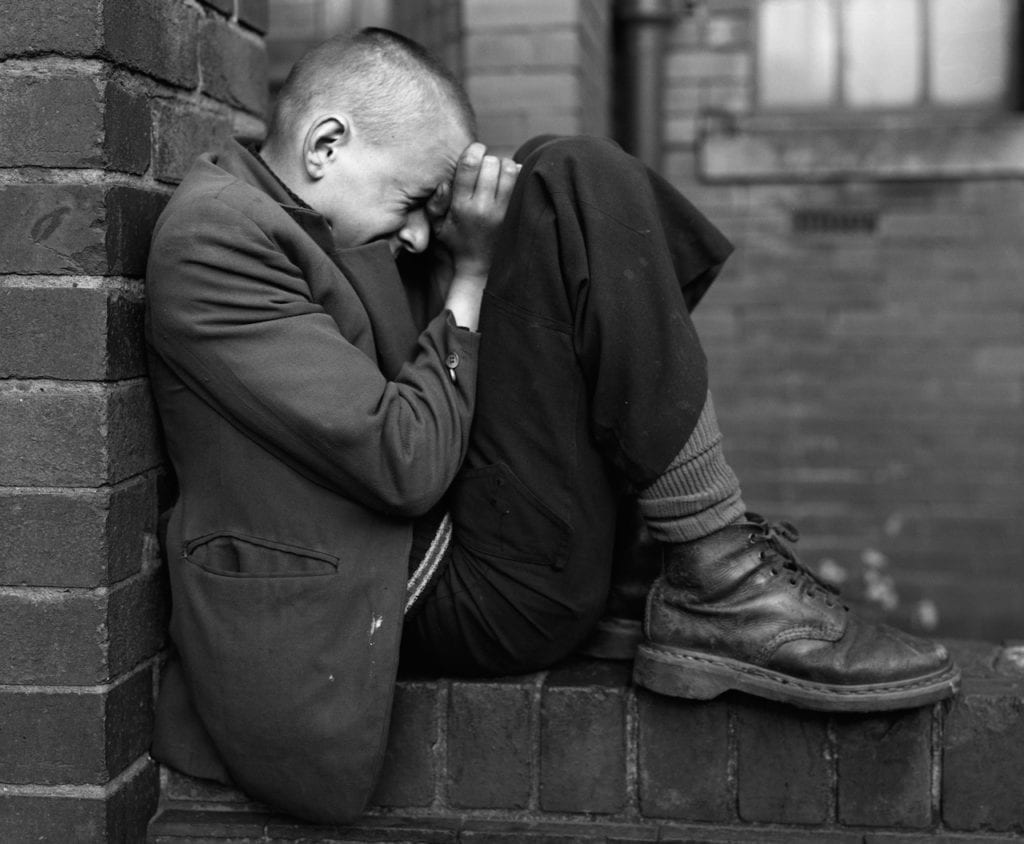

“Sarah Kent in a review said of the Youth on Wall, Jarrow, Tyneside, 1976, ‘This image personifies Thatcher’s Britain’,” he tells me. “I wasn’t worried about that, Harold Wilson was Prime Minister when I took that picture. Thatcher had nothing to do with it! Everyone then stared to refer to Thatcher, though there were four prime ministers while I was photographing. Rather than trying to pin all the blame on Mrs Thatcher, I was trying to pin the blame on all politicians, if that was what I was trying to do. And I wasn’t. I was just trying to say that these people are part of history, these [events] are historical facts.”

For Killip it’s the latest step in an ongoing process that kicked off in 2012, when he was given a major retrospective at Essen’s Museum Folkwang. Going back to his archive to prepare, he found prints he hadn’t looked at in 30 years, he explains – even images he’d never printed. “With me, nobody ever asks for any images except for those in In Flagrante,” he laughs. “Nobody ever came to see me and said ‘What else have you got?’ But doing a retrospective, I actually went back and looked at everything again.”

Doing so, he was thrilled to see how accurately he had recorded the time and place – how specific his images were, and therefore how historically valuable. His shots of ship building look like they’re from another century but they also show the sheer skill of the people involved, he says, in an industry that’s now completely vanished from the region. “Children that have grown up there will have heard about it, but not seen it,” he says. “[But the images show] this is what it was like, these ships were made here, this is how they made them – this place has a history, a big history.”

“It’s very disconcerting because it’s like ‘Did this happen?’” he adds. “If you went there you would have no clue that this is where all this happened. But then I have the evidence. It’s kind of fascinating.”

It seems a dry take on images that were once interpreted as deeply political, but Killip doesn’t see it that way. First, he never believed his images could make a difference, he says, as he’s never believed that photographs alone can be a tool for change. And second, he’s always believed that simply recording peoples’ lives has value – so that they’re acknowledged in the here and now, and so that future generations can understand what they did and who they were.

Killip sees his photography as a kind of “people’s history”, and tells a great story to illustrate it, which starts with visiting an American friend. “He grew up in a square in the centre of Boston, it’s been demolished, it’s now where the civic centre stands and all the municipal buildings, but he was standing there pointing out imaginary streets and who had lived there, who had gone on to make a lot of money, who ended up in jail, who ended up in the mob, who ended up in politics,” he says.

Now Then: Chris Killip and the Making of In Flagrante