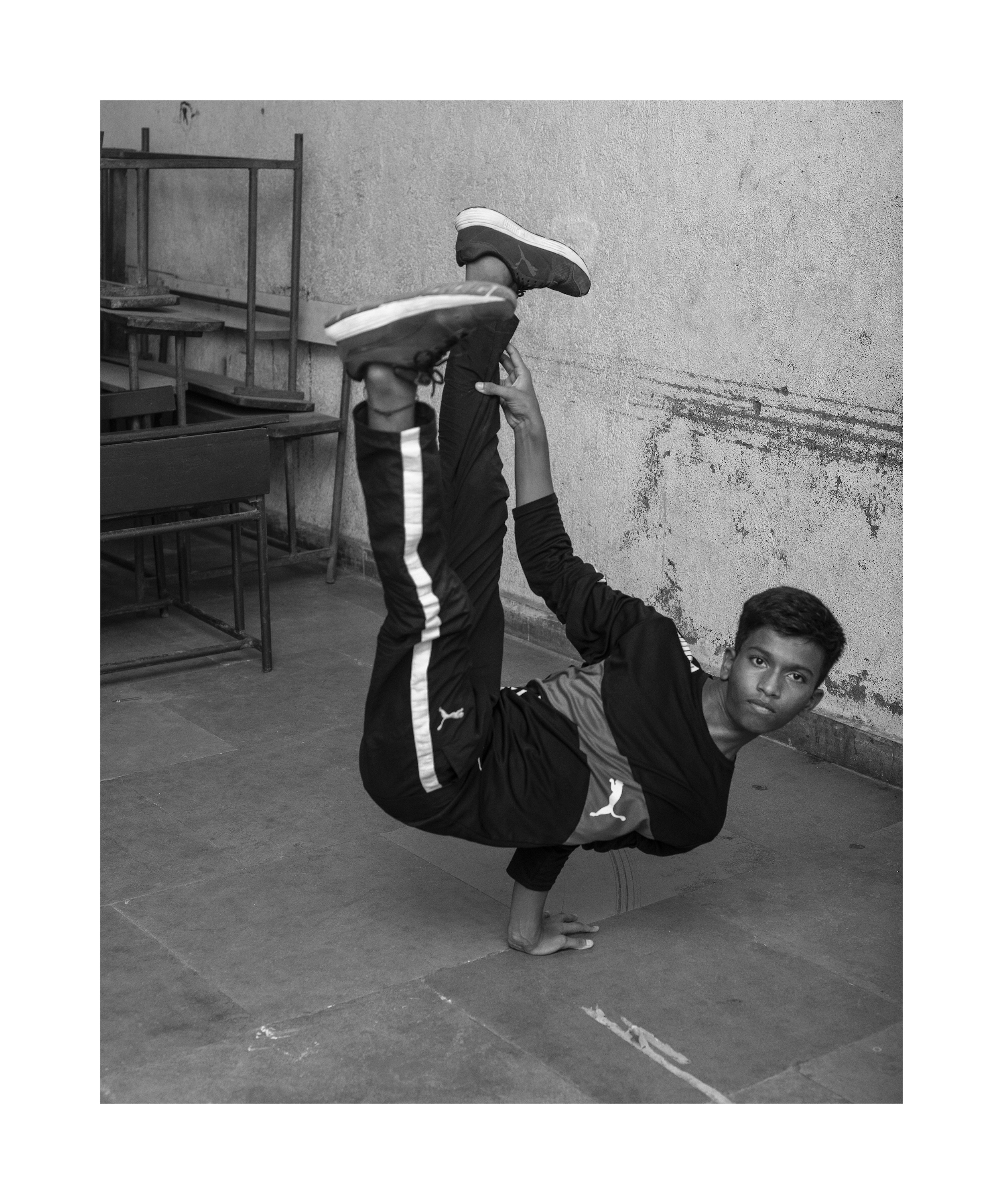

From the series Junagadh © Kalpesh Lathigra

Born and brought up in the UK but returning to his parents’ homeland to make and show new work, Kalpesh Lathigra sidesteps the ‘diaspora dialogue’, says curator Veeranganakumari Solanki

Kalpesh Lathigra was born and brought up in East London, and still lives in the area now; his family is originally from Gujarat, West India, and in his large solo show, The Lives We Dream In Passing, which is now on show in Mumbai, he explores his relationship with India via three separate bodies of work – Memoire Temporelle, The Indian Photo Studio, and Junagadh.

Shot in Mumbai over three years, Memoire Temporelle explores a life that could have been, had his family not migrated; The Indian Photo Studio is a set of identity shots Lathigra found in a street market in Mumbai, then later realised had been made by Gujaratis. In Junagadh he returned to his father’s hometown, exploring streets his dad knew growing up but embracing his position as a Non Resident Indian – a commonly-used phrase in India which describes those who have moved, or were born, elsewhere.

“It’s very easy to fall into the diaspora dialogue, but Kal has very consciously worked on not being in that space,” says Veeranganakumari Solanki, who curated the exhibition at NCPA Mumbai. “That doesn’t mean he has completely gone in the other direction of saying ‘No, I don’t understand what I’m doing’, or ‘I don’t want to be this insider/outsider’. Instead he has embraced where he is at, and developed his own language.”

“It’s very easy to fall into the diaspora dialogue, but Kal has very consciously worked on not being in that space”

Solanki and Lathigra first met in London in 2019, when Solanki was working as a Brooks International Research Fellow at Tate Modern; initially much of her research was around image dissemination, she says, “but something that crept in very quickly was this diaspora question, where almost from the outside I was being asked to keep looking back at home”. Her response was to find artists such Lathigra, whose work tries to push beyond that dialogue, “though I very soon realised that it’s something that’s constantly imposed on them too, as a kind of box”.

Lathigra told Solanki he feels more comfortable shooting landscapes in India, for example, because in England he faces discrimination in the countryside; “there was an underlying sense that, even if he called the UK home, he was never allowed to feel at home,” Solanki says. But she adds that connecting with India is also complicated, particularly in a city as international and as modern as Mumbai.

“It’s very easy for the diaspora to exoticise India, because there’s this desire to hold on to something they feel they are losing,” she smiles. “But in Mumbai you could be in Mumbai, or then you could be in New York. It’s Indian in a very subtle way.”

Lathigra was conscious of “not photographing another cow”, she adds, referencing the overworked cliché of India; his work might be both familiar and unusual to someone who grew up in Mumbai, she says, a perspective that is both ‘inside’ and ‘outside’. She points to Lathigra’s image of a Thums Up cola bottle to explain what she means – on the one hand it could be seen as nostalgic, and even exotic, as it’s an old brand particular to India; on the other hand, Indians have grown up with it, so they are fond of it too.

“It was one of the first fizzy cola drinks in India, Thums Up was a big deal for many of us!” she laughs. “Coca-Cola may have even bought the brand because they realised they couldn’t compete with it. Kal has a large image of the bottle at the start of the exhibition – I’m not sure anybody from here would have done that, but the audience reaction has been that the Mumbai he photographs is the Mumbai we see. Then it’s also a Mumbai Kal has experienced in his own way. He’s had his own vision and insight.”

The identity photographs are something she and Lathigra have discussed for years, she continues, thinking through what they say about individual lives and the bureaucracies that govern them. In the exhibition these images are shown high up in a single line, so that visitors look each person directly in the eye. This area is also painted black, suggesting the photographic studio, or a darkroom, or perhaps what it means to be brought into institutional light.

The final section, Junagadh, reflects Lathigra’s experience of his father’s hometown, a small, traditional place very different to Mumbai. “It’s a tiny, sleepy, seaside town, where there’s no way Kal will be allowed to feel like an insider,” says Solanki. “So he started to photograph the outside from the safety of his hotel rooms. He’s in a space where he can be on his own, without having to perform anything.”

Solanki adds that Lathigra’s desire to make this work says something about contemporary India – areas such as Gujarat have experienced high emigration, and when NRIs then return, they make even sleepy seaside towns more cosmopolitan. She’s also interested that Lathigra has positioned these three series as a trilogy – containing them as a particular part of his practice, beyond which he photographs his family (Nim and Other Stories), or Polaroid portraits of celebrities, or he reflects on the medium of photography, or lectures at the London College of Communication.

“Kal and I have talked for such a long time about bringing this work to India, then the NCPA started reviving their space and it opened things up,” she says. “He was keen to have a show in India because for him it is a homecoming. But perhaps it has also been like a shedding, a way of closing one door and opening another. He has talked about how being an NRI is a kind of freedom – he is an insider and an outsider, he can use that card or not. It’s fluid, and just being ok with that is important.”

The Lives We Dream in Passing by Kalpesh Lathigra is on show at NCPA Mumbai until 06 March. www.ncpamumbai.com