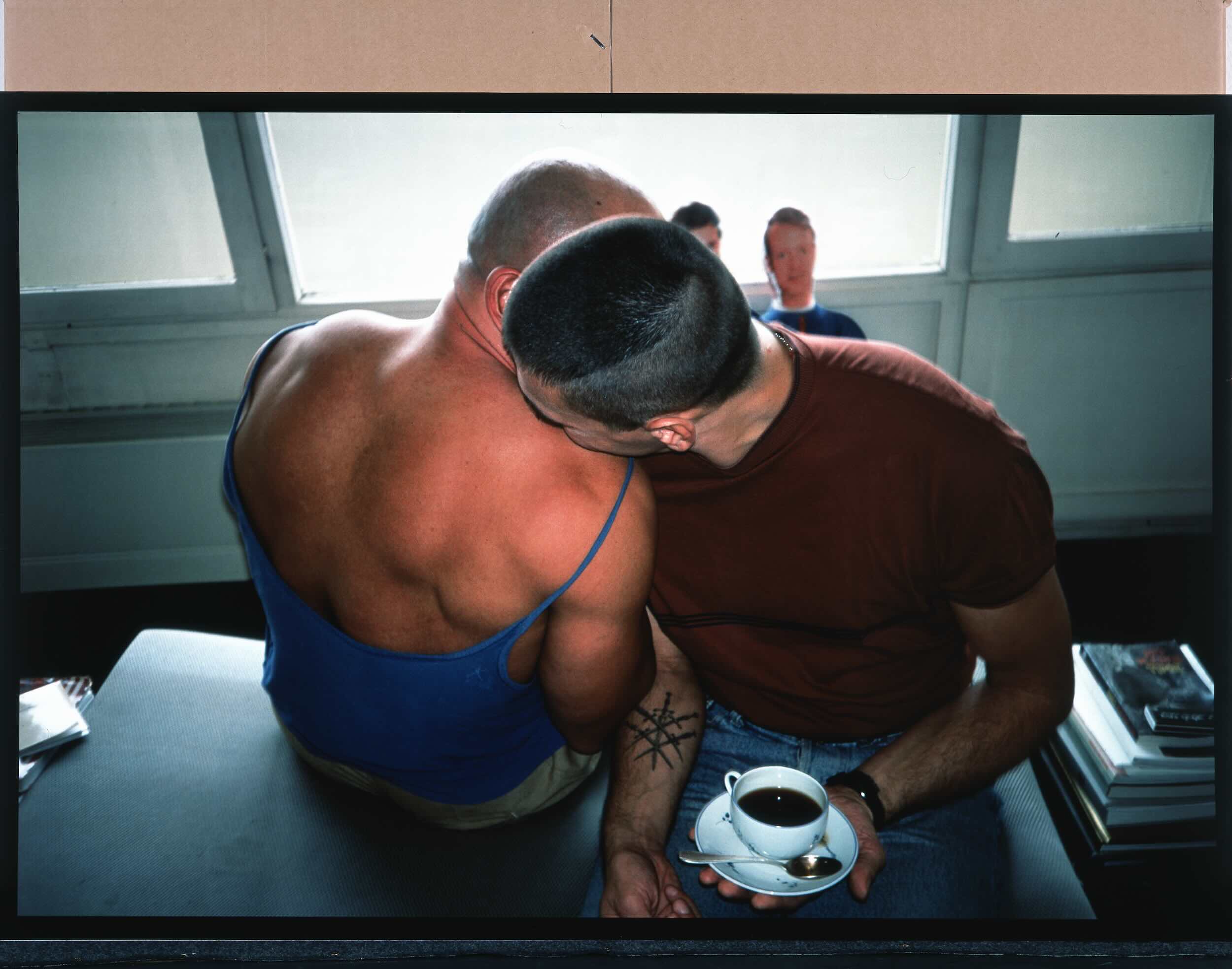

Nan Goldin, Gilles and Gotscho Embracing, Paris, 1992, cibachrome print. Courtesy of Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Torino

VIVONO brings together a range of artists to examine the campaigns and communities of an overlooked era, from the 80s and 90s

From the moment he starts speaking, curator Michele Bertolino makes it clear that VIVONO (‘They Live’) is not just about the HIV-Aids crisis around the period 1982–96. Instead it adopts the era as a lens for examining broader issues, such as time, fragility, intimacy, healthcare, community, visibility and the politics of love. On show at Centro Pecci in Prato, in the Tuscany region, VIVONO – Art and Affect: HIV-AIDS in Italy, 1982–1996 is the first institutional exhibition in Italy dedicated to the history of artists caught up in the crisis, both Italians and those visiting the country.

The exhibition begins with a new film commission by Roberto Ortu, which features poems by Italian writers living with HIV (including Dario Bellezza, Massimiliano Chiamenti, Nino Gennaro, Ottavio Mai, La Nina, Marco Sanna and Pier Vittorio Tondelli) read out by actresses, activists and artists. This sets the tone – poetry as confession, desire and survival, asking, ‘How do we love together?’.

“Now is the right time for this show because it has never been done before,” Bertolino says. “When it comes to this topic in the UK and France or the US, we know tonnes of artists who work around the topic of HIV-Aids, and they are all superstars. We don’t know about any Italian artists. As Italians, we decided to forget that part of history.”

“How do you build an alliance that goes beyond your identity?”

Curated by Bertolino in collaboration with archivists and activists, the exhibition avoids dividing works by medium. Documents and artworks are presented on equal footing, blurring the line between testimony and art. This archive, co-developed with Valeria Calvino, Daniele Calzavara and I Conigli Bianchi, is central. Displays include posters, newspaper clippings, video fragments and sound recordings, interlaced with contemporary interventions by Emmanuel Yoro and Tomboys Don’t Cry. The design, by Giuseppe Ricupero, uses daylight, white tones and mobile structures to balance institutional gravity with intimacy, evoking domestic and communal spaces.

In Italy HIV-Aids was not confined to the gay community, Bertolino explains; 80 per cent of diagnoses were recorded in the injecting drug-user community with sex workers also hugely affected. People in prisons, because of the laws against drug users in Italy at the time, were also disproportionately affected, with about 40 per cent of the prison population HIV-positive. “So HIV in Italy is intersectional – it touches many different communities,” the curator explains. “The show asks, ‘How do you build an alliance that goes beyond your identity?’.”

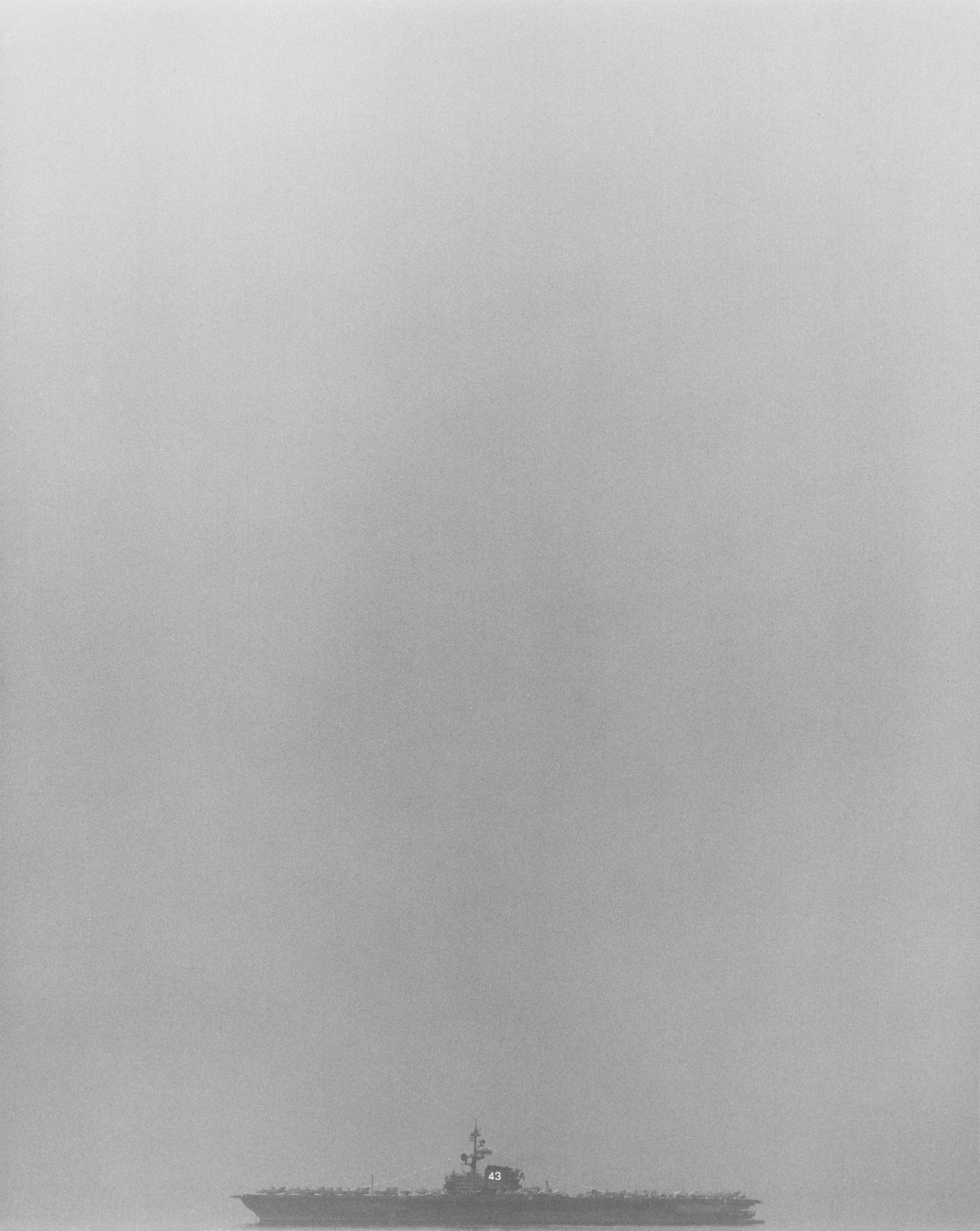

International names are present, but their inclusion is always grounded in Italian histories. There is a shot by Robert Mapplethorpe titled Coral Sea, for example, taken from the artist’s Naples hotel room in 1983; it shows a vast sky plus a slim profile of an American army ship (the US then had operational control of the Gulf of Naples). “It’s a very non-Mapplethorpe photo,” says Bertolino. “That for me became immediately the best photo possible to speak about desire, but also to speak about distance.”

Nan Goldin’s images are also embedded in this Italian framework via three images made in Naples in 1986 when she visited with friend Cookie Mueller. She was “basically running around in Positano”, says Bertolino, “one photo of a vase of flowers in front of the seaside, and another photo with Cookie overlooking the sea.” Later, in the 1990s, Goldin photographed the so-called ‘Junkie Madonna’ shrine in Naples’ Forcella district, a site deeply marked by drug use.

And then there are the Italians. Roberto Caspani is better known as a painter, but VIVONO includes a photo series he made in 1983, displaying simple shots of sea foam. “They create patterns that change very quickly,” observes Bertolino. “And it’s a way to block time, to reflect about this idea of how do I approach time when I don’t have time anymore? How do I extend it or how do I freeze it?”

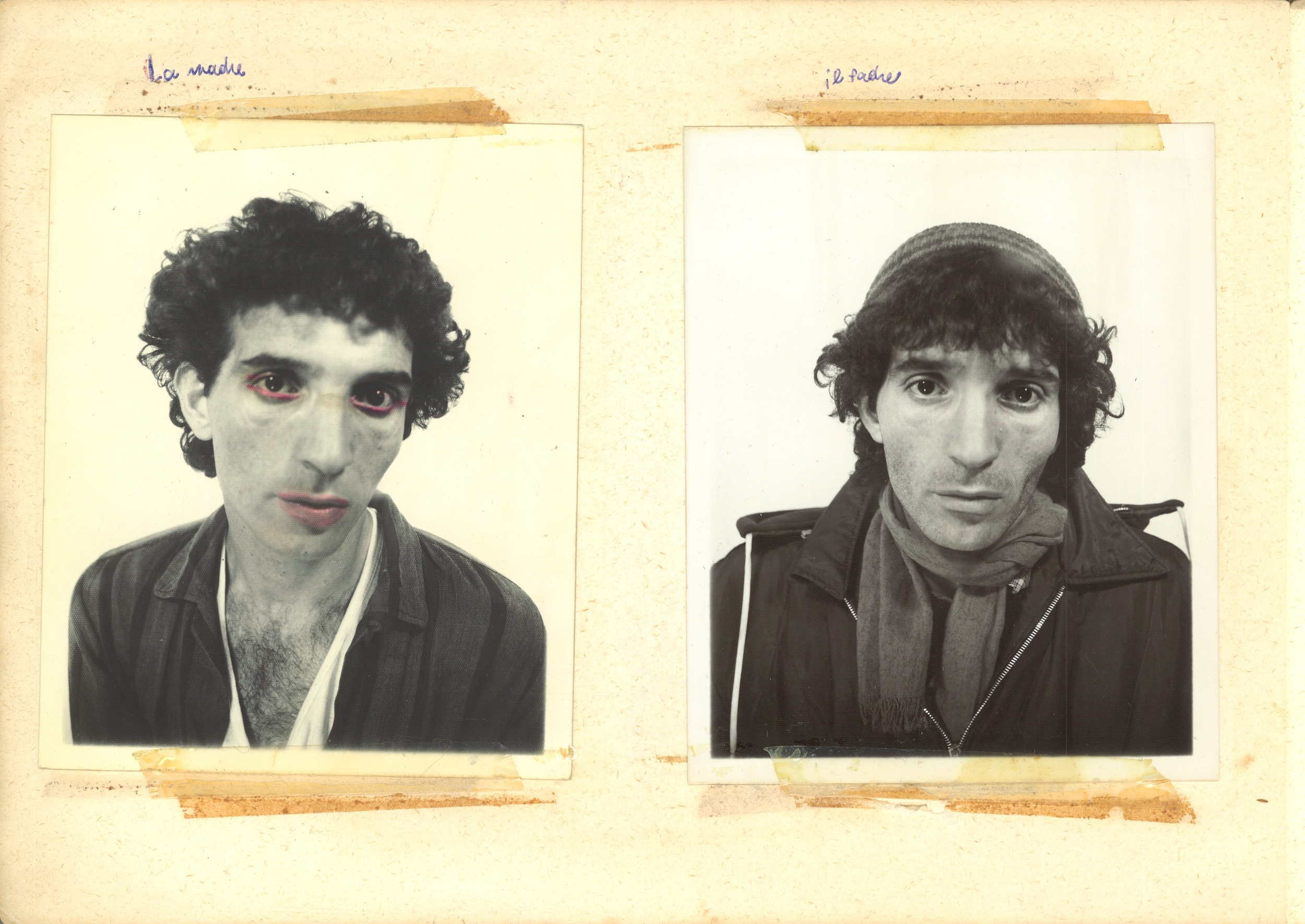

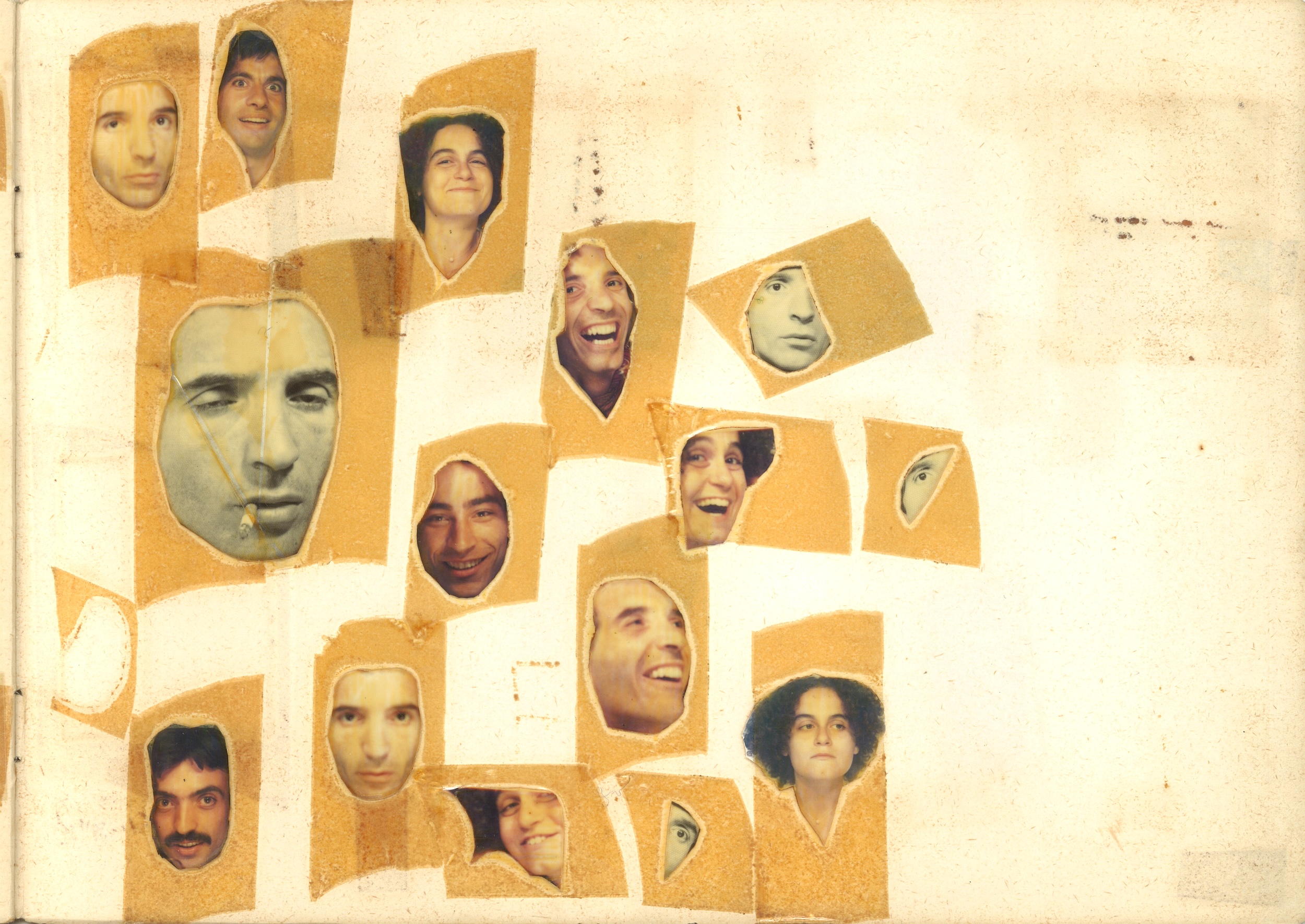

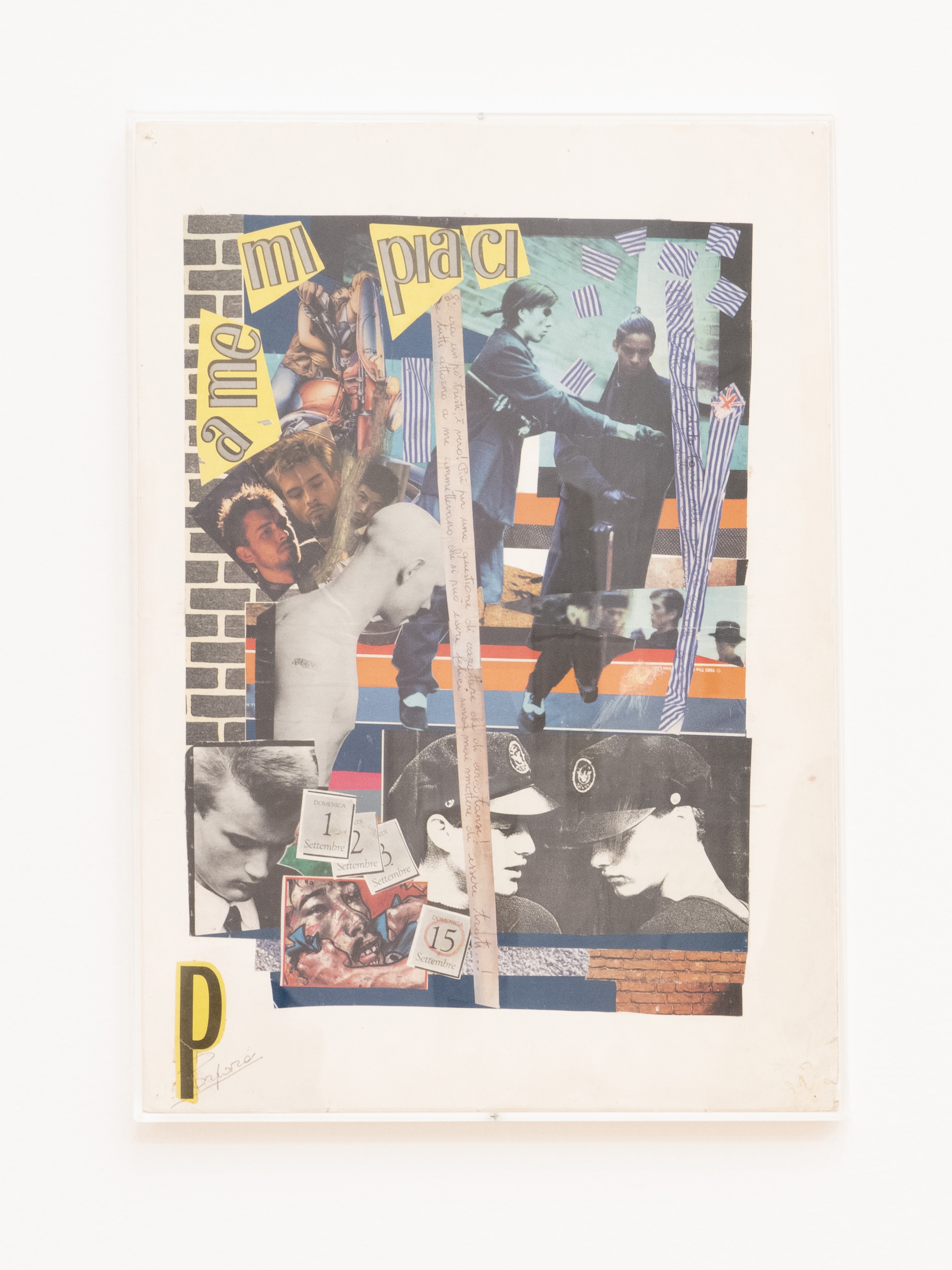

Elsewhere, Bertolino describes Nino Gennaro with great affection. “When it comes to photography, his approach was not shooting directly,” he says. “It was using photographs by other people and mainly photographs that friends were doing. He was also working a lot with the photo booth and acting on these photos with adding colour or glasses or drawing. His work is very much about the question of representing himself. And his answer was, ‘I am never myself, I am always with others. It’s this bond with others that allows myself to be here, to exist’.”

Equally affecting are the portraits of Lovett/Codagnone, three black-and- white shots of the artists – the former American and the latter Italian – naked, in collective embrace with a third friend. They took these three photographs after a night out. “They partied together, they had their drugs and things, they had a lot of fun I imagine. And then they went home and they undressed and they started to shoot this portrait, which is literally a portrait of a chosen family,” Bertolino narrates.

Unlike past Aids exhibitions foregrounding mourning, VIVONO insists on joy, intimacy and collectivity. “It’s limiting to always talk about HIV as a moment of death,” Bertolino says. “Which of course it was, but it was such a generative time that we cannot even imagine how generative it was in terms of alliances, fights. You have to remember that we were people in our twenties and thirties. There were moments where we were just thinking about having fun. And if you want to do a show on HIV-Aids and at that time, you cannot forget that we wanted to have fun.”