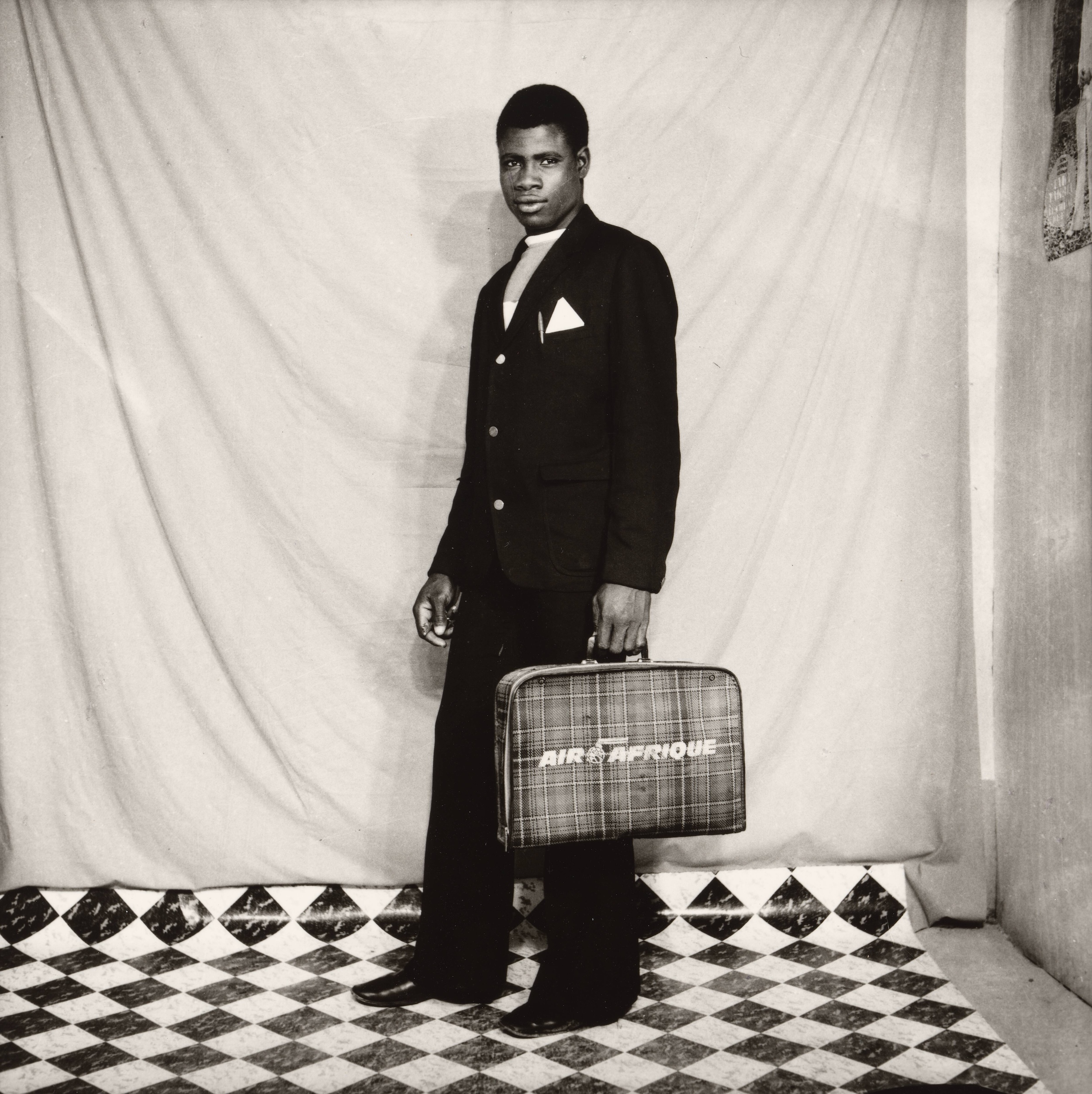

© Oumar Ka Estate, courtesy Axis Gallery, NY

How did portraiture shape a vision of pan-African possibility? A new show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art explores the ways images of everyday citizens informed political ideology

Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination, at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, explores how portrait photography has helped circulate ideas of pan-African solidarity and subjectivity. Mixing classic images from the 1960s, works from the African diaspora and more recent approaches, it includes iconic work by Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé and Sanlé Sory, plus artists such as Samuel Fosso, Silvia Rosi and Njideka Akunyili Crosby.

Unusually the exhibition is not arranged chronologically, and it also freely mixes artists from various places. “The exhibition’s curatorial approach and spatial organisation encourages an interpretive reading of the histories of photography on the African continent and in the African diaspora, rather than a chronological, monographic, or geographic frame,” explains Oluremi C Onabanjo, The Peter Schub Curator at MoMA, who curated the show. “In substance and form, Ideas of Africa encourages viewers to be sensitive to the circulation of ideas and images across space and time.”

The exhibition name and concept draw on The Idea of Africa, a key text published by VY Mudimbe in 1994. Mudimbe “rigorously unpacks the systems of knowledge about the African continent that were developed in and circulated through European and North American traditions of philosophy and critical theory”, writes Onabanjo in her catalogue essay.

“Ideas of Africa encourages viewers to be sensitive to the circulation of ideas and images across space and time”

Noting that “the stakes of narrating histories of photography in Africa are unquestionably political”, Onabanjo explores how the political imagination has been reflected and shaped through photographic portraiture. Expanding the portrait beyond an index of individual identity, she locates images – and sitters and photographers – within “the ephemeral, aesthetically rangy, culturally plural sense of ‘continental unity’”. She points to the wave of independence which swept Africa in the 1950s and 60s, alongside the Civil Rights Movement in the US, and argues that the potential these shifts engendered allowed image-makers to create “dazzling modes of pan-African possibility”.

By way of an example, she cites Jean Depara, an image-maker who set up his studio in Kinshasa (then Léopoldville) in 1954, when the city was home to nightclubs and a thriving music scene; in documenting it, she argues, Depara showed an imaginary created by those freed from the everyday. Sanlé Sory did similar in Bobo-Dioulasso in recently independent Burkina Faso, in nightclubs, the streets, and his studio, Volta Photo. Seydou Keïta opened his studio in Bamako in 1948, meanwhile, creating what Onabanjo describes as “sublime compositions that rendered Bamakois citizenry in the process of becoming”.

To this rich mix, Ideas of Africa also adds contributions such as Oumar Ka’s less-known images from Senegal, which push beyond glamorous urban centres and into the countryside, and JD ‘Okhai Ojeikere’s documentation of Nigerian culture – plus images such as Untitled (Photo Shoot at a School for One of the Many Modelling Groups Who Had Begun to Embrace Natural Hairstyles in the 1960s) by Kwame Brathwaite, who lived and worked in the US. Contemporary artists such as Fosso and Rosi both continue and deconstruct these approaches, with Fosso creating intricate self-portraits reinhabiting icons of Black history in his 2008 series African Spirits.

“Does photography materialise a particular way of seeing? Yes, but a contingent one – open to myriad theoretical modalities, subjective positions and critical interpretations,” says Onabanjo. “When considering histories of photography, it is apt to consider deploying a bifocal mode of looking – where two images can be held in tandem.”

Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination is at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, from 14 December 2025 to 25 July 2026