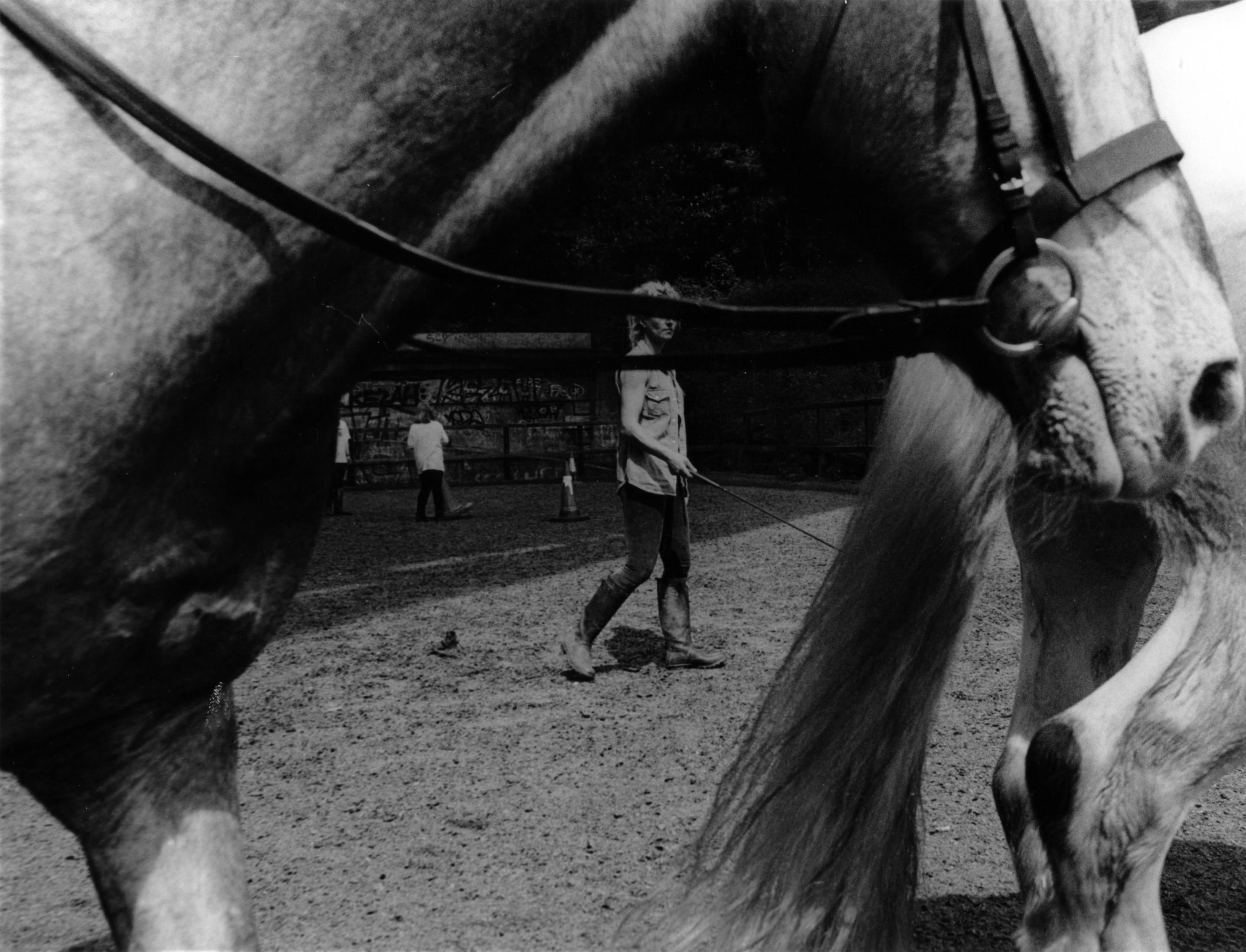

Unknown. Courtesy of Stepney Archives.

The filmmaker returned home to shoot Stepney Western by taking cue from the archives of Tish Murtha, Mik Critchlow and Chris Killip

Harry Lawson’s initial impetus for creating Stepney Western was cinematographic. Straddling the porous boundary between fact and fiction – familiar terrain for the filmmaker – this experimental “urban Western” was made in collaboration with a group of young inner-city horse riders from Stepney Bank Stables in Newcastle. The documentary is kaleidoscopic in nature, weaving together original footage of the stables with archival materials from the North East Film Archive (NEFA) to form “a web of Western aesthetics that’s not been seen before”.

“At first, it was more of a creative challenge,” Lawson explains. “Can you make a Western when you’re denied all the things that make a classic Western so recognisable? The expansive landscapes, the desert, and so on.” But after approaching Stepney Bank for their involvement, it soon became clear just how far the genre would resonate.

Founded in 1992 in Newcastle’s Byker-Ouseburn neighbourhood, a half-hour drive from Lawson’s family home in Sunderland, Stepney Bank is both a riding school and a young people’s charity, running youth projects such as their Alternative Provision programme to support children on the fringes of mainstream education. “The organisers understood immediately why you’d want to make a Western there,” Lawson says. “Paula, the deputy manager, told me: ‘Life really is like the Wild West for these kids.’ I understood over time what she meant by that.”

“Instead of cowboys pillaging land, the way I see the frontier narrative today is this slow but sure gentrification”

Shot over a two-year period, during which Lawson became deeply embedded within the stables, what emerges from the film and the accompanying exhibition of archival photographs currently on show at Newcastle Contemporary Art is a compassionate portrait of the city’s urban horse riding community, and the North East at large.

Sitting down to watch around 50 Westerns in preparation for filming, the most striking theme for Lawson was “the frontier narrative” – stories of westward expansion and colonisation. “I started thinking about the ways the Byker neighbourhood has been developed over the years through many cycles of regeneration projects,” Lawson explains. He trawled through hours of archival footage from NEFA, looking for “sprinklings” of Western aesthetics – motifs like “campfires, fiery red sunsets, a sense of the ‘epic’” – but also instances of dramatically changing landscapes. Most evocative are grainy clips of wrecking balls and terraced houses being demolished to make way for the Byker Wall estate – Ralph Erskine’s ambitious architectural project from the late 1960s to the early 80s, which came to represent a kind of failed utopia for the neighbourhood.

While your typical Hollywood Western might feature the advent of the railroad – “generic shots of laying down tracks” – Lawson inserts footage of the Tyne and Wear Metro system under construction in the 1970s. And where gold rush tales might unfold, we glimpse Newcastle’s defining 20th century resource: coal. In Lawson’s collagic, non-linear style – “my approach to archive is to try and collapse disparate things into one contemporary moment” – the film gestures towards the rise and fall of the mining industry. Vintage clips of coal-gathering ponies are intercut with traces of Thatcherism and the deprivation that followed in the wake of deindustrialisation.

Fast-forward to the present, and the contemporary “land grab” playing out in Newcastle is quieter but more insidious, Lawson suggests. “Instead of cowboys pillaging land, the way I see the frontier narrative today is this slow but sure gentrification – the pricing out of young people through swanky restaurants and coffee shops,” he explains. “A tension starts to build. If the kids can visit the stables but can’t hang out in the surrounding neighbourhood, how is that community being held? Where does it go from here?” Stepney Bank itself has felt the threat of rising costs, narrowly avoiding closure thanks to a crowdfunding campaign last spring.

Through Lawson’s empathetic lens, you get a feel for just how precious the place is. Among Stepney Western’s motley cast of kids, the hero – or anti-hero – is undoubtedly Ella, whose Alternative Provision programme happened to run in parallel with Lawson’s filmmaking. The documentary follows her from the age of 14 to 16, tracing her poignant evolution from local troublemaker, exiled from mainstream education, to earning qualifications in equine care. A true “outlaw,” Ella is headstrong, quick, and utterly endearing – someone who, as Lawson notes, “can’t help but be herself” in front of the camera. Pressed on the importance of gaining her English GCSE, for example, Ella quips that she’ll just “use Duolingo”. As her mother summarises: “Before Stepney… the police were at the door every night. But now there’s no police at the door whatsoever, and it’s down to them horses.”

At points, the film’s pace slows, with rapid cuts and flickering imagery giving way to scenes of stillness and care between the individuals and the horses. In these longer takes, away from the chatter and exuberance of the stables in full swing, a relationship of true reciprocity becomes apparent. “Of course it’s great for the kids to learn equine skills, but by learning to love and respect the animals, you see a massive change in their ability to love and care for other people, and eventually, to love and care for themselves,” Lawson remarks. “That’s probably the most ideal kind of nurturing a young person in that situation could receive.”

Working so collaboratively with the kids introduced rogue elements into Lawson’s creative process on a visual level. Realising early on the impossibility of banning iPhones from the shoots, he encouraged his protagonists to capture their own footage, remixing it into the film alongside fragments from the 2004 CBBC series The Stables, made with teenagers at Stepney twenty years ago. We see pixelated shots of hacks and jumps from the riders’ POV, replete with TikTok filters of cascading love hearts and sparkles.

“What I love about their footage is that it’s intensely antithetical to my aesthetic,” Lawson smiles. “There’s a generative point of tension between what I would like to do with the Western – my sweeping directorial vision of recasting the North East in this way – and their different points of importance. Ella does not care for what I like in cinematography, she cares for having a pink fluffy cowboy hat in the film because that’s the hat she wants. That was really exciting to me, to ask, ‘how can young people bend a project to their will?’”

In this way, Lawson’s documentary is shot through with playfulness. The same can be said for the accompanying exhibition at the NCA. Viewers sit on hay bales to watch the film, and the archival photographs – varied shots of locals and horses from the past century – are hung at a deliberately lower height to make the space more accessible to children. Taken from the archives of AmberSide and the Ouseburn Trust, the black-and-white images are displayed “democratically”, with lesser-known local photographers such as Davey Pearson appearing alongside celebrated documentarians of the North East like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Chris Killip, and Tish Murtha.

The condition of “youthfulness” was key to Lawson’s image selection, even when it came to more “bittersweet” impressions of the region’s industrial past. He points to one photograph by Derek Smith from the 1970s; a field of daisies flowing down to a steelworks. “To me, this is an incredibly youthful image,” Lawson reflects. “There’s a distinct way in which depictions of the North East usually take shape – this ‘it’s grim up north’ aesthetic. And that’s just not the experience I had while making this film. The kids are full of energy and vitality, and I’m able to feel so hopeful about the North East through them.”

Having spent ten years living and working in London, the documentary marked Lawson’s return to his hometown in more ways than one. “During filming, I realised in quite a heartfelt way that I only want to make work here for the next however many years,” he says. “When it comes to ethical art-making, the headline for me is sustained engagement – with a place or community. Without wanting to sound too grand, I feel that the contribution I can make to the arts should be here in Newcastle. I feel very interested in people’s lives here, more so than anywhere else.”

Through its intergenerational patchwork of visuals and voices, Lawson’s documentary remixes the Western genre in ways that feel significant on both a cinematographic and a community level. It reimagines the dominant cultural narratives surrounding the North East’s social and industrial history, and – perhaps most importantly – envisions new perspectives on class, community and care-giving for the future.