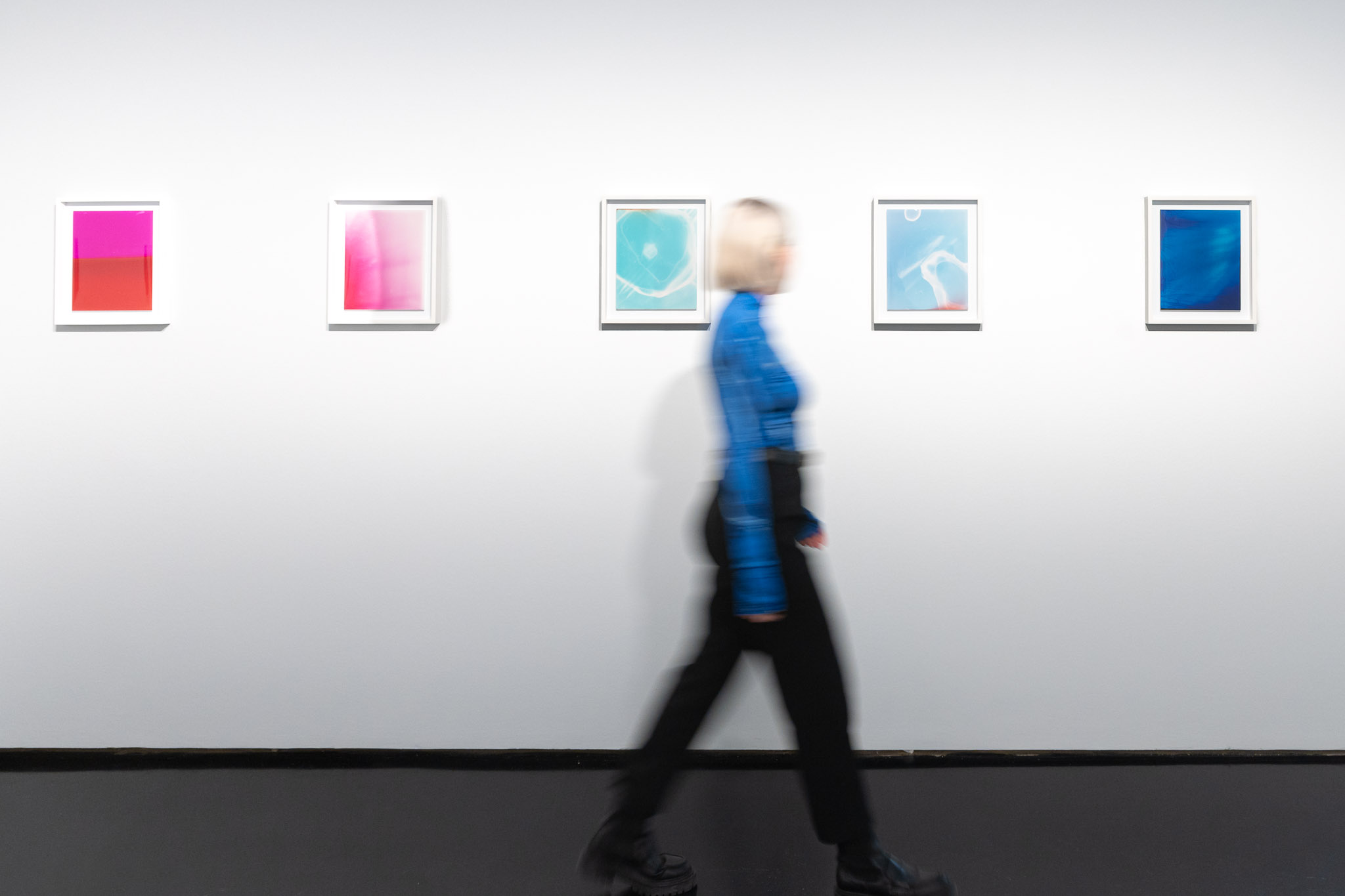

© Abril Wotjas

After 18 years at C/O Berlin, and three years setting up the fledgling FOTO ARSENAL WIEN, Felix Hoffmann is spearheading its move into a large new home in a historic postwar building

“We are still under construction, but we’re aiming to open on 21 March,” says Felix Hoffmann. “The first day of spring.” It is a gloomy December as we speak but we are discussing bright new beginnings – the permanent home for FOTO ARSENAL WIEN, the state-funded contemporary photography gallery of which Hoffmann is artistic director. It is moving into a refurbished 1950s building in a historic former military arsenal, which offers 1000 square metres of space for a cafe, education rooms, offices, and a gallery with moveable walls allowing for large group shows and smaller projects. FOTO ARSENAL WIEN will open the new venue with an exhibition devoted to Magnum photographers Susan Meiselas, Bieke Depoorter, and Rafał Milach, digging into their image archives and considering how we approach such collections. But it will also include a smaller series by emerging Vienna-based artist Simon Lehner, in which he explores his own family photographs and questions issues around power and politics.

Hoffmann joined FOTO ARSENAL WIEN in 2022, shortly after the project won backing from the Austrian government; he arrived from C/O Berlin, where he had previously worked for 18 years, and which he had similarly built up from the ground. He plans to programme eight to 10 shows per year at the FOTO ARSENAL WIEN, changing the exhibitions every few months and including international touring shows as well as original projects. Also lined up for 2025 is Science/Fiction, a group show travelling from Paris’ Maison Européenne de la Photographie, and the blockbuster Daidō Moriyama exhibition.

“When I started, there was some discussion around making a space related to Vienna,” he explains. “But I thought, I can bring a little more international fluidity with other partners in Europe. There are projects which I already started in Berlin, for example. Take the Daidō Moriyama exhibition – I helped the curator, Thyago Nogueira, build its European tour, and it started in Berlin and will end in Vienna.”

“Sometimes you see a picture which is famous and iconic, and it’s not a good picture, and so there is always the question, ‘Why did it become so iconic?’”

Initially FOTO ARSENAL WIEN had a temporary home in the MuseumsQuartier Wien, where it hosted work by cutting-edge image-makers such as Laia Abril and Karolina Wojtas. But the plan was always to move into the Arsenal, which is based in south-east Vienna and also hosts a military museum, the archive of the Austrian Film Museum, opera rehearsal studios, and apartments. Hoffmann points out it is only a 10-minute walk from the main train station, but concedes it is less central than the MuseumsQuartier and will need to become a destination.

“The Arsenal is like a village in the city, and we’re thinking how to develop it,” he says. “The site is quite big, and some of the other buildings are empty; it also includes green space and is next to a park, and that brings another element. I am hoping to activate those areas with public installations, particularly during FOTO WIEN.”

FOTO WIEN takes place every other year and is part of the European Month of Photography; one of Hoffmann’s early tasks was to organise the 2023 edition, and FOTO ARSENAL WIEN will look after it in 2025 and beyond. Taking place across the city, FOTO WIEN includes events in private galleries, studios, and institutions, with well over 100 programme partners involved last time. The 2025 edition will be similarly expansive but Hoffmann plans to make the FOTO ARSENAL WIEN a focal point, organising a book fair, a symposium and other exhibitions and events there. The 2023 FOTO WIEN discussion programme focused on Ukraine and Poland and he plans to expand on that this year too, particularly as EMOP includes many Eastern European capitals, “and as Eastern Europe is an interesting place, politically”.

In the ‘off’ years when the EMOP is not happening, FOTO ARSENAL WIEN will organise another festival, Vienna Digital Cultures. It is part of an ongoing partnership with Kunsthalle Wien, the city’s state-run contemporary art museum and FOTO ARSENAL WIEN’s ‘sister’ institution; put simply, Kunsthalle Wien and FOTO ARSENAL WIEN will take it in turns to organise the annual Vienna Digital Cultures. It is a new venture but based on an existing model – originally conceived of in 2020 as the Festival of Media Arts, the festival explores the intersection between contemporary art, lens-based media, digital culture, and technology.

On top of this, FOTO ARSENAL WIEN is joining Futures, the network of European institutions which champions emerging image-makers. Co-funded by the European Union, it also includes organisations such as CAMERA (Italy), FOMU (Belgium), and Void (Greece). “Futures is very interesting and so vivid,” says Hoffmann, adding, “I have a small team, five or six people, so we will not get bored [at FOTO ARSENAL WIEN]. It’s really a challenge to build up this structure.”

This challenge is partly what attracted him to the job, having done something similar with C/O Berlin; the German institution gained the name ‘C/O’ because it moved venues so often in its early years, before settling in Amerika Haus in 2014 (another converted 1950s venue, Hoffmann jokes he loves construction sites). Unlike C/O Berlin, FOTO ARSENAL WIEN does not have a permanent collection, instead following the ‘kunsthalle’ exhibition model popular in northern Europe (and also followed by The Photographers’ Gallery in London). Hoffmann will spend about 50 per cent of his budget on staff and another 25 to 30 per cent or so on the venue, leaving 25 per cent or less for the programme; he will need to raise additional funds via ticket sales and donors, he says, adding that one of the reasons he wanted to co-organise Vienna Digital Cultures was that it gave him budget to employ a digital curator, in a co-hire with the Kunsthalle.

More philosophically, working on the festival involves exploring images as they are now most often encountered – online – expanding on the FOTO ARSENAL WIEN’s remit to cover the everyday and the near-future more broadly. “For the 2026 Vienna Digital Cultures we will be focusing on immersive, digital questions,” he explains. “Of course we will also do that at the FOTO ARSENAL WIEN, but where that is related to photography and lens-based media, on the other hand we have the question of what is surrounding us.”

This question still underpins much of Hoffmann’s thinking at the FOTO ARSENAL WIEN, because he believes the ready online availability of photography has shifted the role of institutions. Where once galleries offered places to encounter images, now at least part of their responsibility is to stop the visual flow “for half an hour, maybe 20 minutes – we have to work fast”. Similarly, now that we encounter so much information via images rather than text, we need to learn media literacy as much as basic literacy. He is planning a strong educational programme at FOTO ARSENAL WIEN, encouraging visitors to think how to handle this “inflation of visual culture”, including how to organise their digital archives “or even how to just delete some images”.

The FOTO ARSENAL WIEN educational programme will also drill down into the history of photography, and the building will include an analogue darkroom, accessible via its own entrance, in which users can literally get to grips with the medium. The next generation is fascinated by analogue and alternative processes, Hoffmann points out, valuing their sheer physicality over the ‘virtual’ on-screen world. “When I started in C/O Berlin in 2005, the first thing we moved out and put on the street was the darkroom, because these were digital times – we didn’t need a darkroom!” he says. “Then the first thing we reinstalled was a darkroom. This chemical process on a piece of paper is a kind of magic – something happening there, not just ink laying onto a piece of paper.”

But thinking through visual culture also goes deeper than the contemporary moment or the physicality of images, and through the programming and curation at FOTO ARSENAL WIEN, Hoffmann hopes to prompt broader questions about photography and power. During Paris Photo he co-organised a conference at MEP with Magnum Photos, for example, in which Magnum photographers, and curators such as Florian Ebner (Centre Pompidou) and Simon Baker (MEP) discussed archives and their use; part of the build-up to the forthcoming exhibition at FOTO ARSENAL WIEN, it also highlighted the circulation and distribution of images – key issues that often get lost or overlooked.

“Sometimes you see a picture which is famous and iconic, and it’s not a good picture, and so there is always the question, ‘Why did it become so iconic?’,” Hoffmann muses. “The answer is, it became iconic because we know it, because it circulated so much. Say there’s a photograph of Nixon and Khrushchev during the Cold War, it’s not a good photograph but it’s transmitting something, and then it’s enormously circulated, it’s published in Life magazine. You know, in the period before TV, Life had a distribution of 6 million magazines per week, and there were something like eight people reading each magazine. Certain images were just burned into our consciousness – this is important to recognise.”