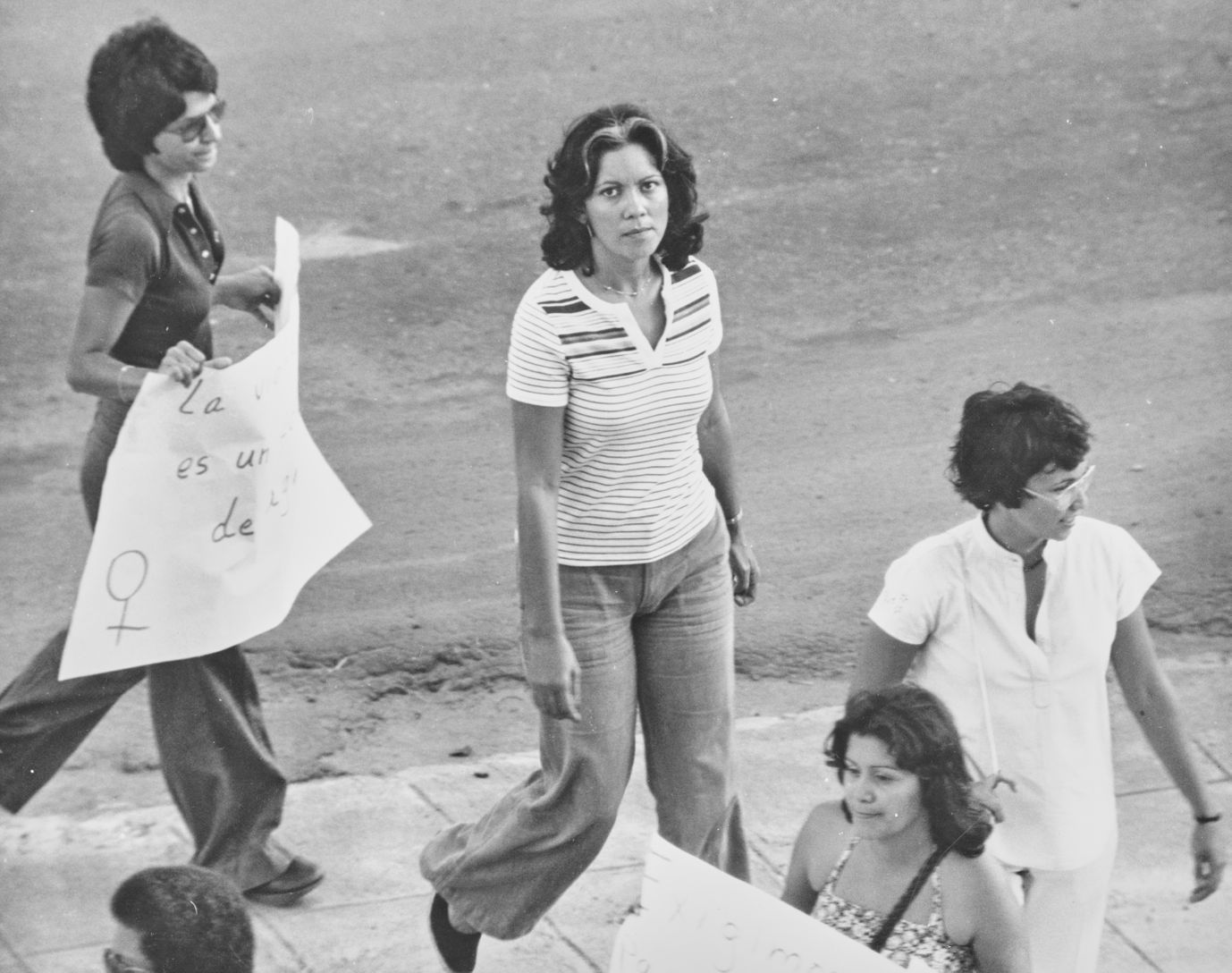

Women Marching, from El Gobierno Te Odia [The Government Hates You] © Christopher Gregory-Rivera

Questions around surveillance and control circle around the photography at FORMAT Festival, now on show in Derby

FORMAT International Photography Festival returns with the theme “Conflicted” and a programme which “focuses on the many struggles, tensions, and conflicts that define our time”, according to Jodi Kwok, curator of FORMAT and QUAD arts centre, and Jenna Eady, FORMAT co-ordinator. “We invite everyone to reflect on the challenges we face, from global crises like climate change and migration to personal struggles related to identity, freedom, and social issues,” they continue in their catalogue essay.

Kwok and Eady add that photography plays a crucial role in highlighting these problems, but snaking through the exhibitions is also a healthy suspicion of images, their power, and their use to survey and control. Originally from Hong Kong, Kwok has included several interesting political projects in the festival, including BJP’s FORMAT25 Award winner We Didn’t Choose to be Born Here by Thero Makepe; Makepe’s work considers personal experiences of the struggle against apartheid, contrasting his immediate family’s life in Botswana with his extended family’s more radical, difficult time in South Africa. Individuals resist his lens and disappear from view and, in the installation at the Museum of Making, wallpapers and framed prints overlap and collide. Creating an elusive combination of planes, Makepe pushes against the surveillance which led to his grandfather’s uncle, the activist leader Zephaniah Mothopeng, being repeatedly harassed and jailed.

“We invite everyone to reflect on the challenges we face, from global crises like climate change and migration to personal struggles related to identity, freedom, and social issues”

Jodi Kwok, curator of FORMAT and QUAD arts centre, and Jenna Eady, FORMAT co-ordinator

Over in Chapel Street, Christopher Gregory-Rivera presents a jaw-dropping work titled El Gobierno Te Odia [The Government Hates You], using images made by the US government of its own citizens. From the 1940s to 1987 the Puerto Rican Police, in collaboration with the FBI and CIA, watched, intimidated, and attacked political activists in the archipelago, which remains a US territory. The secret operation tracked over 150,000 people and compiled dossiers on over 15,000; it only came to light in 1987, after a long investigation into the execution of two university students by the Puerto Rico Police Intelligence Division. The dossiers were returned to those tracked and, as with the Stasi in East Germany, showed that friends, relatives, and neighbours had all been involved in the surveillance, creating lasting divisions for a population in which victims and spies still live side-by-side.

Gregory-Rivera’s work demonstrates that individuals were sometimes aware they were being watched, creating a panopticon effect in which everyone had to constantly modify their behaviour; the secret police has since been disbanded but this means of control continues, Gregory-Rivera including a video from 2017 in his installation. Made by the police, it documents lawful protestors, some of whom went on to be wrongfully arrested; in the ensuing court case, it transpired that there were many other videos, and that Facebook had shared personal data and conversations from individuals who had interacted with online footage of protests. These examples have ramifications for citizens everywhere, and Gregory-Rivera has also made a book of this work which deserves to be widely seen.

The showstopper of FORMAT is Felicity Hammond’s installation at QUAD, V2: Rigged, the second iteration of her ongoing project, Variations. Supported by Photoworks and Ampersand Foundation, Variations is an ambitious project around data mining and AI; the first variation, V1: Content Aware, popped up in a public square in Brighton in October 2024 at the Photoworks Weekender. Ostensibly a shipping container, V1: Content Aware included a camera recording those passing by, and V2: Rigged includes images generated from that footage. Many of those who had interacted with V1 had taken photographs of it, notes Hammond, and when she fed images of them into an AI generator, it churned out depictions of men wielding hybrid camera-weapons.

Hammond’s response is a large installation with a similarly sinister edge; part-camera, part-drill, part-processing plant, it is extracting further data from visitors, while a huge mirrored wall alludes to both their surveillance and an endless duplication of images. A large pixellated backdrop includes some of the AI images of men generated after V1: Content Aware, “documentary expressions of society’s views of itself” as Hito Steyerl has put it (quoted in the festival catalogue). The next iteration of Variations, V3: Model Collapse, goes on show at The Photographers’ Gallery in London in summer and will lean further into escalations of our collective imagination; the final variation at Stills Gallery, Edinburgh will investigate how data is corralled and catalogued.

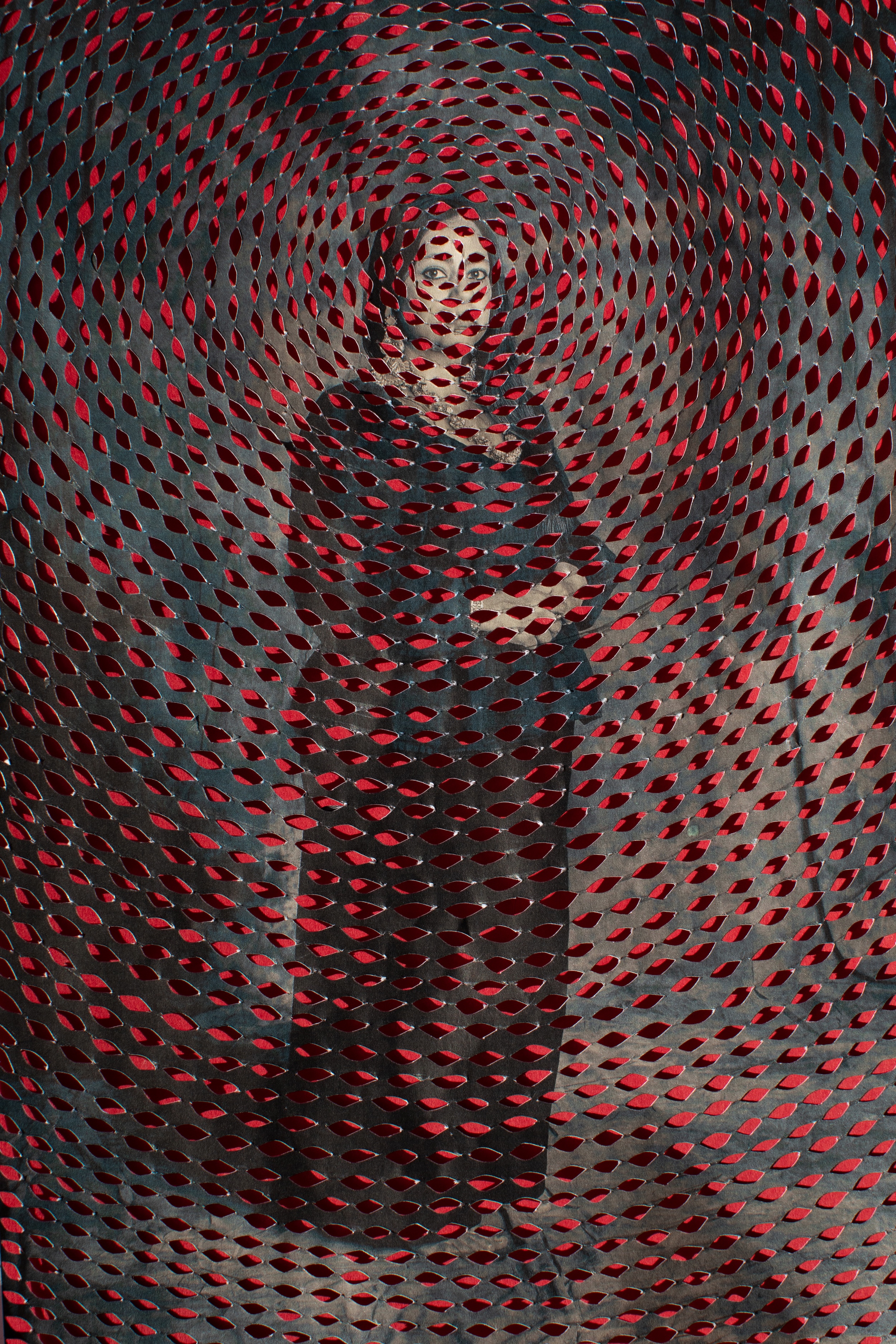

Next to Hammond’s work, Sujata Setia’s A Thousand Cuts also suggests (male) surveillance and control. Working in the UK with domestic violence survivors from the South Asian diaspora, Setia made portraits then sliced intricate patterns into the prints. Inspired by the tradition of Sanjhi art, these cuts afford the women depicted anonymity, suggesting a means of escape but also the lasting impact of their experiences. Setia collaborated with the women to make their portraits and the carved motifs, allowing them to govern their own depiction, just as they have retaken control of their lives; she also recorded interviews which are included in the installation, testifying to how they fell into abuse, and how they managed to escape. The colour red dominates, signifying the optimism of marriage – red is the traditional colour for South Asian wedding dresses – and the violence all too often perpetrated at home.

An unholy mix of the everyday and the ultraviolent runs through the exhibition OUR RIUKZAK at University of Derby too, a group show of work by Ukrainian photographers curated by Lesia Maruschak. Combining images of the Ukrainian Holodomor famine-genocide of 1933-34 with photographs of the contemporary conflict, it is designed as a portable exhibition-in-a-box which can pop up in various venues. The title references the rucksacks into which families stuff scant essentials before fleeing home, and the present-day images focus on children; there are powerful shots of terrified parents running into hospital with bleeding infants, and buggies being pushed through chaos. Another nearby group show of work from Ukraine strikes on a more complicated note, however; On the Thorns of Evil Ages includes portraits of armed forces volunteers made by Anton Shevelov, an Officer of the Armed Forces of Ukraine and the Special Correspondent of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine.

Elsewhere are other series around physical conflict. Jenna Garrett’s Teeth of the Wolf is an eerie exploration of armed vigilantes in the US, for example, inspired when she saw online images of Proud Boys leader Enrique Tarrio, standing in front of the State Capitol shortly before his fellow protestors stormed the building. Garrett was reminded of images of the Bald Knobbers, a group that sprung up in the Ozark Mountains after the American Civil War, which was responsible for lynchings, beatings, and arson. America’s volatile political situation also surfaces in Alicia Bruce’s The Greatest 36 Holes? Coming Soon, which shows a golf course Donald Trump built in Scotland. Constructed on an area designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, this course attracted considerable local opposition and though Trump announced it in 2006, long before becoming US president, is a cautionary tale foreshadowing his pronouncements on Gaza and Greenland.

Intriguing images made during World War One by the still-running WW Winter portrait studio show German officers in internment camps; the officers look curiously pampered, suggesting either propaganda at work, or special treatment for the upper class. Elsewhere are interesting installations around the environment, including Lo Lai Lai Natalie’s The Days Before the Silent Spring, and Xueyi Huang’s AI project, No.27 Tong Poo Road. Other exhibitions feel perhaps more tangential, including an exhibition of Michael Omerod’s American roadtrips at the University, and John Blakemore’s Earthly Delights at the Museum of Making. Maybe they testify to the needs of external venues included in the festival (Museum of Making just acceded some of Blakemore’s prints), or the wide appeal required of a public event.

Dancing Through Time also speaks to wide appeal but in a more lively way; an archive of images, ephemera, and oral history, on show in a former clothes shop, it traces the progress of music and clubs in Derby, of shared experiences that build cohesion rather than conflict. It also celebrates the DIY ethos of punk, particularly necessary in a small city, and offering potential solutions amid contemporary funding cuts for musicians and artists. Upstairs, Francis Augusto’s Ghost Notes does something similar, showing one-time stalwarts of Derby’s punk scene today; these elders have much to teach younger generations about self-organisation and making things happen.

The reclaimed store feels appropriate but actually we are far from the freedom of 1960s and 70s squats; in 2012 UK laws around property tightened up, and using this venue took months of careful negotiation. FORMAT continues to be a critical plank in the UK’s photography ecology, but how it will evolve in the current political and economic climate remains to be seen. The same can be said of photography, and it is a strength of Kwok’s curation that perhaps the biggest conflict on show here is around images, how they are used and by whom.

The FORMAT International Photography Festival exhibitions are open until various dates; for details check www.formatfestival.com. BJP is a FORMAT Festival sponsor