All images © Jurga Ramonaite

In Beneath the Surface Skin, chemigrams made with Arctic seawater and glacial portraits become letters across loss

Jurga Ramonaite grew up hearing her father’s stories of travel under Soviet occupation, when journeys beyond Soviet territories were rare and precious. Years later, encouraged by him to visit the Arctic, she made the journey for both of them. Beneath the Surface Skin – her debut solo exhibition at Raleigh Chapel – transforms those Arctic photographs into an ongoing conversation through the physical act of darkroom printing.

During the Soviet occupation of Lithuania, travel beyond Soviet territories was largely restricted. Ramonaite’s father managed to travel through sport, and after independence in the early 1990s, mobility took on new meaning for her family – associated with learning, exchange, and opportunity. Years later, when he became ill and spoke about wanting to visit the Arctic, he encouraged her to apply for The Arctic Circle residency. She went in 2025, overcoming her fear of open water to spend two weeks sailing through the archipelago of Svalbard. He passed away two months after her return.

In the months that followed, Ramonaite returned to the North London photographic studio and colour darkroom she co-founded – part of a broader movement of photographers returning to analogue processes. For her, the choice is both practical and conceptual. “The slowness, physical engagement and presence required working with film, and analogue processes feel like a resistance to the current fast pace of contemporary image culture,” she explains. The darkroom community she’s helped build fosters collaboration – people working alongside one another, sharing techniques, discussing works in progress – in contrast to what she describes as the surprising isolation of commercial photography.

“Working in the darkroom – slowly and methodically – feels like a form of conversation”

But in this body of work, the darkroom functions as something more than technical infrastructure. “Working in the darkroom – slowly and methodically – feels like a form of conversation,” Ramonaite says. “Each step of the process becomes a sentence and each finished print is a story.” She printed all the works herself, at scale, through repeated test exposures, filtration adjustments, dodging and burning, and hand retouching. “Each print becomes almost like a letter, carrying effort, care and attention.” The hours spent in chemistry and darkness become inseparable from the work’s emotional function – a physical act of memory-keeping.

The exhibition spans three interconnected series. Breath of Air consists of two chemigrams made aboard the ship during the residency, using Arctic seawater, kelp, and light. Ramonaite set up a makeshift darkroom in her cabin’s bathroom and left the organic material on photographic paper for the full two weeks, allowing it to decompose and chemically interact with the emulsion. Some areas became completely bleached; others developed sediment-like traces in greens, yellows, and oranges. “I’m interested in slow processes and in treating time as a collaborator,” she says. “These works engage with the idea of slow violence – forms of harm that unfold gradually and without spectacle, often going unnoticed until their effects become irreversible.”

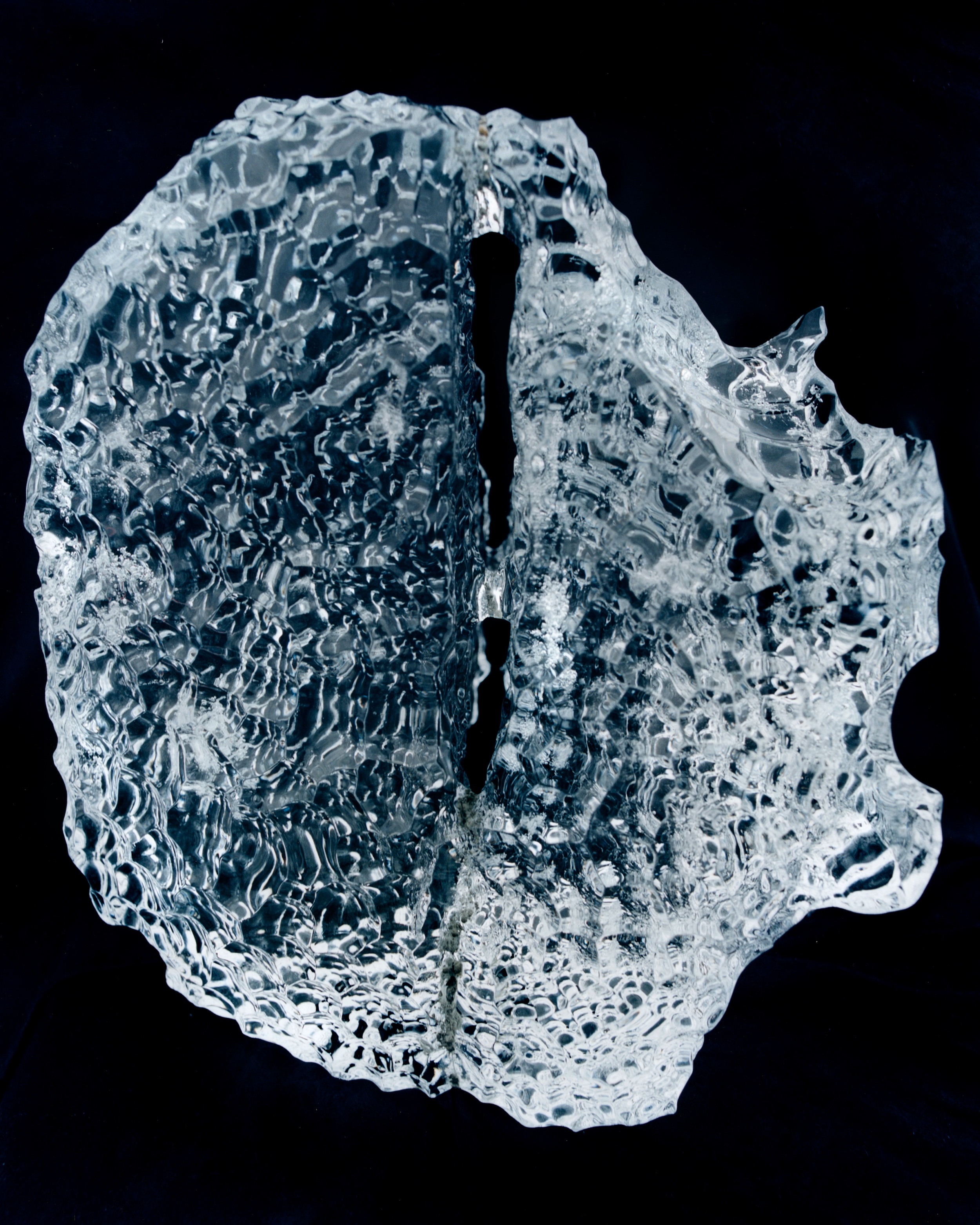

The Glacial Portraits series isolates fragments of ice against black fabric, photographed from a small zodiac boat before the clarity of the ice began to cloud. As glaciers form, air and sediment are trapped; over centuries of compression, air bubbles are forced out, creating remarkable glass-like clarity. “These fragments function as time capsules,” Ramonaite explains, “holding and preserving memories of an environment long past.” Photographing them against black allowed her to capture the moment of clarity before melting made the surface opaque.

The show also includes five works from the Landscapes series, where photographic emulsion has been altered by light and water, and concludes with The Line – a looped film tracing the Arctic horizon, accompanied by a four-speaker sound installation by Mathias Arrignon combining field recordings and synthetic textures.

Across all the works, the act of preservation remains inseparable from loss. “I still feel there are countless stories I didn’t have the opportunity to share,” Ramonaite says of her father. “Continuing this project has become a way of honouring him.” The Arctic, she adds, “became a liminal space where personal and ecological grief was intertwined.”