All images © Ezekiel

Somewhere between a doll and a dog chronicles, over several years, the stages of transition and transformation, following the artist moving between the UK and their homeland of the Philippines

“So if you don’t know, don’t give up,” sings Lana Del Rey on the song “Margaret”, from 2023’s Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd, “’cause you never know what the new day might bring… maybe tomorrow, you’ll know.” It’s an album that fizzes with ambivalence – on time, family, fertility, identity and even Del Rey’s own oeuvre, which gets picked over, re-sampled and reworked, troubling the contours of her creative and personal growth. Lana is an artist who doesn’t simply poach across boundaries of taste and style, she all-out violates them, parlaying a range of gender, race and class stereotypes to construct a picture of a modern, complicated, libidinal woman – as Jia Tolentino writes, “at once artificial, but authentic to the world we live in”.

“I think she’s one of the greatest songwriters of our generation,” says Ezekiel, the Filipino-born, Margate-based artist and filmmaker. We’re discussing the process of making Somewhere between a doll and a dog, Ezekiel’s searing new photobook, published by the POC-led, trans and queer creative direction studio SMUT, with the support of Studio Moross. The book features a dizzying sequence of film and iPhone photographs, along with scanned letters and diary extracts, that compose a “visual archive of transness” accumulated across the UK, the Philippines, Europe and the USA between 2021 and 2024. It was a period during which Ezekiel listened to Lana Del Rey on repeat, along with early Madonna, another artist known for skewering the cliches of authenticity within modern pop music, as well as the contradictory notion of female empowerment under capitalism. Lana appears in the book around a third of the way through, or at least her avatar: seemingly caught in a moment of serenity, eyes closed as if in prayer, on a 50ft high stadium screen. Her image reappears, more ghostly and refracted, in a sea of mobile phone screens bobbing beneath. The “real” Lana, in as much as it’s possible to say that one exists, is outside of the frame somewhere, significantly smaller no doubt, and vulnerably corporeal.

As with many projects exploring trans experience, Somewhere between a doll and a dog depicts bodies undergoing processes of transformation and refraction, from chest binding and nose jobs to late-term pregnancy. Water reoccurs as a motif, with all its associations with cleansing, renewal and spiritual rebirth. “I feel like in the West we are conditioned from the very beginning to be ashamed of our bodies, and scared of other people’s bodies,” Ezekiel tells me.

“But the more I came into my transness, the more I actually learned to love my body. I was like, I’m gonna do this really radical thing and actually just love myself.” However, they are keen to emphasise the ways that trans experience transcends visual presentation, whilst challenging the idea that trans bodies are problems to be solved with make-up, clothing, hormones or surgery. A particularly reprehensible feature of contemporary right-wing discourse around trans people is the obsession with surgery, and the need to fit individuals into neat categories based on physical characteristics.

“I was around a lot of butch women who would go by male pronouns, men who would cross-dress, and trans cousins. That was just the norm”

Instead, Ezekiel makes liminality and ambiguity the full story, locating beauty in a form of metamorphosis that never fully arrives at a fixed form. “Are you a doll?” the artist was asked once at a party; their response gives the book its title and its grounding proposition, which is less about dolls and dogs (although both appear, in their figurative forms, in the book) and more about “somewhere”. So many of Ezekiel’s subjects seem to be suspended in a state between one thing and the next, evading actualisation. Somewhere between effeminacy and machismo, somewhere between ancestral knowledge and contemporary truth, somewhere between East and West.

“I’d always known that I never wanted to grow up as a man,” Ezekiel reflects. “And I didn’t really know whether I wanted to be a woman either. I didn’t learn the words for that indeterminacy until later on in life. Because I grew up in a home of broken English, I always have this weird voice in the back of my mind that tells me I’m not good at English and that I’m bad at expressing myself through words. This is actually why I think I am a photographer – it’s like a universal language that I speak and that other people can understand.” Tagalog, the language Ezekiel’s grew up speaking in their native Philippines, does not feature gendered pronouns.

The Philippines is one of Southeast Asia’s most tolerant countries toward queer and transgender communities; despite colonial Spain’s imposition of Roman Catholicism in the sixteenth century, gender-nonconforming and trans spiritual figures were revered as healers in indigenous Filipino mythology, bridging the gap between spiritual and earthly realms. Lakapati, the goddess of fertility and agriculture, is one of the most idolised figures in the pre-colonial pantheon, and is depicted as an intersex or trans deity, collapsing binary concepts of gender.

“I was exploring my experiences of gender in the Philippines before we immigrated here when I was six,” Ezekiel explains. “I was around a lot of butch women who would go by male pronouns, men who would cross-dress, and trans cousins. That was just the norm. I rarely had to interrogate my gender expression. And then coming to the West and moving to a Catholic primary school in Brighton, I was basically told: OK, you’re a boy, this is how you’re going to live your life. This is how you’re going to dress.” The artist’s return to the Philippines in late 2024 became a pivotal point in the development of the work, opening up a space for them to imagine transness outside the Western binary: complex, spiritual and in tune with the natural world.

The photobook’s sequence, which takes influence from the publishing work of Wolfgang Tillmans, also takes a loose approach to categorisation, bringing images together according to slippery or abstract themes, but continually looping back, repeating and reordering, like memory itself.

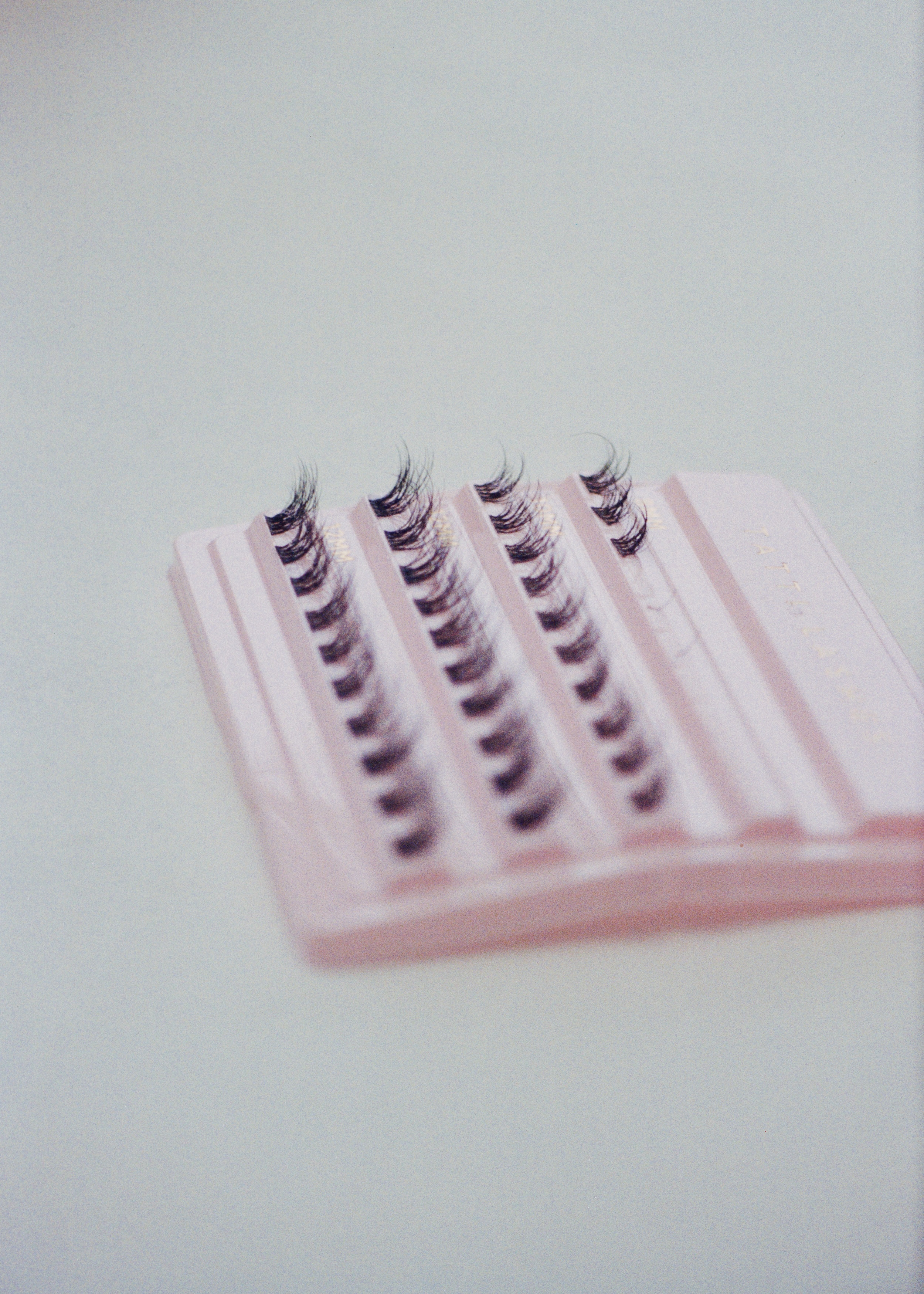

Part of Ezekiel’s process for the project was to insert themselves into hyper-masculine environments, such as men’s football clubs, male strip show green rooms, and gyms. In all of these scenarios, instead of intimidation, they are met with warmth and openness. In a particularly poignant sequence, having just got their eyelashes done in Manilla, Ezekiel takes a taxi to an open-air men’s prison on the Filipino island of Palawan. They buy a comb in the prison gift shop, handmade by an inmate, and have it engraved with their name, now their only name, and perhaps one of the only aspects of Ezekiel and their work that symbolises fixity, alongside silver halide and dye on gelatin.

So if you don’t know, don’t give up. “Ocean Blvd came out in March 2023 around the same time that I started shooting this project and was experiencing some really intense gender dysphoria. I would say this is one of the many albums that soundtracked my travels across the continents, as well as my days in the darkroom, where I spent many hours hand printing over three hundred images. It’s one of Lana’s most vulnerable pieces of work, reflecting on family, existentialism, spirituality and self – ideas that my book also touches on.” Somewhere between a doll and a dog emerges as a profoundly cathartic and emotionally-charged body of work, including imagery almost too painful to share, for fear of judgement.

“I’m finding that vulnerability can be something so powerful and necessary,” says Ezekiel, “not only for myself, but for anyone who engages with this body of work.”