Petra Collins in collaboration with Jenny Fax. I’m Sorry © Fish Zhang

GIRLS: On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between gathers decades of images, memories, from Jim Britt’s iconic Sisters to contemporary reflections on the rituals of growing up

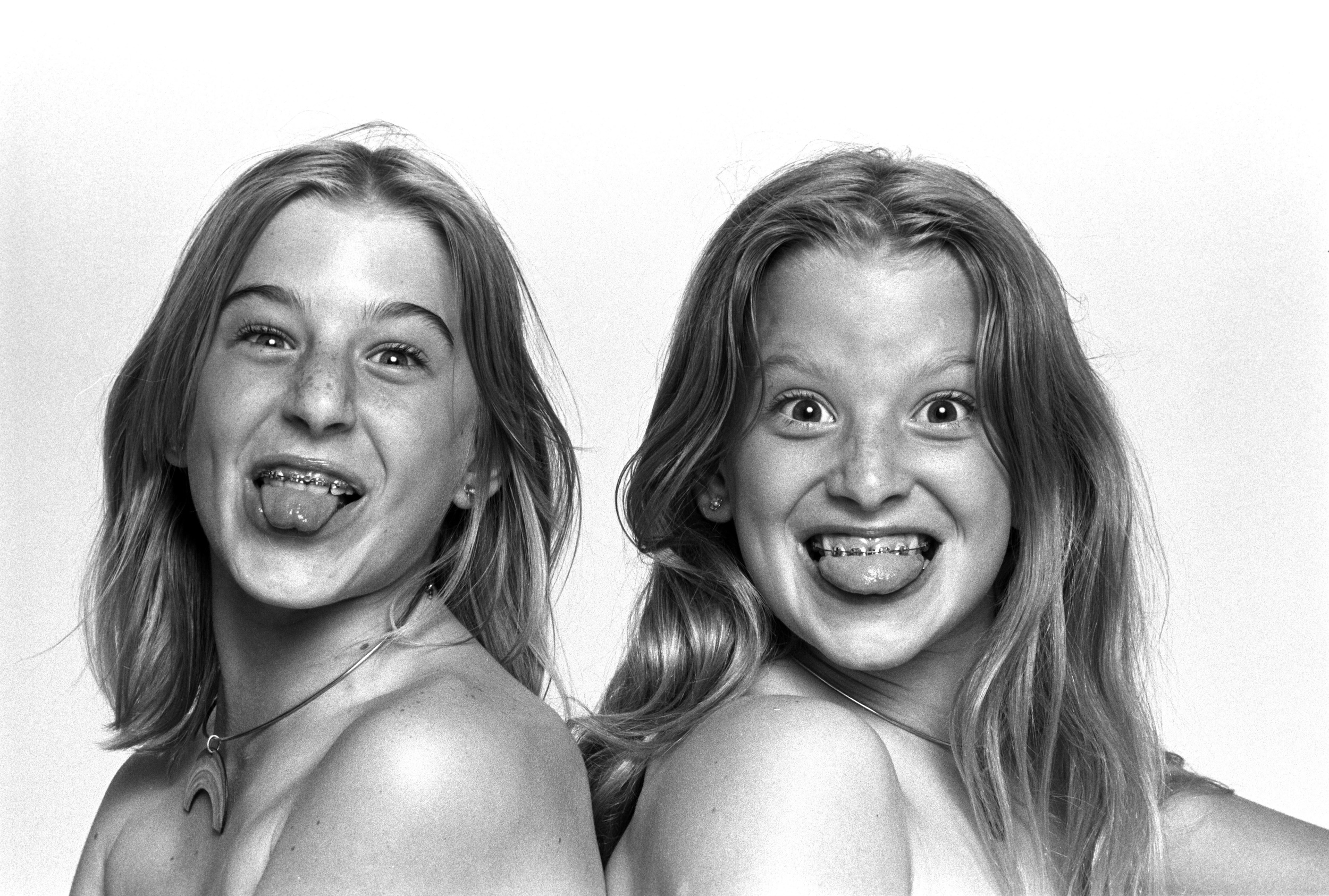

First published in People magazine in 1984 – later resurfacing in a Comme des Garçons campaign for AW88 – Jim Britt’s Sisters is a brilliant display of girlhood. Shot at the photographer’s home in Los Angeles in 1976, his daughters Melendy (Mimi) and Jody radiate with a specific type of joy that befits their near adolescence; they wear bright, laughing smiles that show off their braces, and correlating moon and rainbow jewellery around their necks. “It was for fun,” shares Britt, “I had no agenda other than that, but these photos seem to have since touched so many people.” In 2018 the extended series was published as a book (accompanied by a double-sided poster), while more recently Sisters has been adopted by MoMu in Antwerp, where a picture of the girls playfully sticking their tongues out at one another announces the exhibition, GIRLS: On Boredom, Rebellion, and Being In-Between.

Curated by Elisa De Wyngaert, GIRLS is a tenderly articulated survey of the ways girlhood has and continues to be interpreted – both as a way of seeing and as a vehicle for shaping visual culture – exploring in particular how the realms of fashion, art, film and photography have considered, applied, and sometimes interrogated, ideas typically consistent with the aesthetic language of girlhood. Works by Simone Rocha, Alice Neel, Molly Goddard and Frida Orupabo feature, circumnavigating three core bedroom installations (the first with costumes from Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides, the latter two collaborations with Jenny Fax and Chopova Lowena); Claire Marie Healy, additionally, has curated ‘Girls in Film’, a montage of clips that examine how clothing operates in cinema as a means of self-expression.

“For many women artists and designers, adolescence has always been central to their work and continues to shape how they see and understand the world. And photography, because of its immediacy, can capture a sense of intimacy and awkwardness – that mix of playfulness, spontaneity, and self-awareness – in a way that slower media can’t,” offers De Wyngaert in an email. “I wanted then, to include photographers from different generations who have shaped how girlhood is portrayed. Nuanced and unique visions of girlhood; work that never treats girls as objects but approaches them with respect, often co-created or shaped by the teenager’s personal boundaries and agency.”

“There’s a vulnerability and strength in how girls move through the world”

Distributed around the space via projector, in frames upon walls, and delicately displayed in vitrines (see, the 2018 Sisters poster), in practice this looks like Lauren Greenfield’s iconic Girl Culture series (2002) and Nigel Shafran’s Teenage Precinct Shoppers (1990); Nancy Honey’s 2001 series Girls Shopping, and Micaiah Carter’s Adeline in Barrettes from 2018. Juergen Teller’s SS07 campaign for Marc Jacobs, starring a pre-teen Dakota Fanning in specially-made catwalk looks, also appears, while Roni Horn’s This is Me, This is You (1997–2000), a collaboration with her niece Georgia, notably features towards the exhibition’s end. “I placed this series in the closing section because it speaks to two meaningful ideas,” advises the curator. “How quickly time passes during that stage of life, and that the most compelling works don’t portray girls as distant, voiceless muses, instead engaging them actively in the creation of the work.” Indeed, Horn followed her niece’s lead throughout the project, culminating in 96 close-up portraits of Georgia going about her life.

Elsewhere, Eimear Lynch’s Girls’ Night (2023), for which she travelled across her native Ireland photographing the ceremony of a night at the local disco – teenagers doing their make-up, gossiping with friends, and getting dressed up – is underpinned by the idea of creating a kind of dialogue between the images and the photographer’s own memories of growing up and enacting similar rituals. “The work comes from a place of recognition; my own experience of girlhood is definitely woven into it,” says Lynch. “I’m also inspired by the honesty and intensity of that stage of life, how everything feels heightened and meaningful. There’s a vulnerability and strength in how girls move through the world.”

In her essay Girl Code: Conceptualising the Girl of Fashion, which appears in the accompanying catalogue, Morna Laing, a professor at The New School, Parsons Paris, observes that “the concept of ‘the girl’ has elastic boundaries… one can remain a girl long after leaving girlhood; or at least that is what language would have us believe.” It’s a sentiment many of the works on show lean into, including Fumiko Imano’s ongoing twin series (which, coincidentally, appears on the catalogue’s cover enwrapped in a heart-shaped cutout). Beginning during her studies in London in the early 2000s, the Japanese photographer produces self-portraits, cutting and sticking photos together to create a twin in the same image. “I started when I tried to fit into adulthood but I couldn’t,” she explains of the concept’s genesis. “I wished I could stay as a child, because I don’t feel like I’m experiencing womanhood the same as a normal woman – I haven’t given birth [for example]. But I wasn’t necessarily considering myself as doing ‘girls’ things, I have just always been counted in a ‘girls’ category.”

Steering the wider exhibition is the common understanding that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to examining or participating in girlhood – it means, feels and looks like different things to different people, hence the scope of GIRLS. This is made clear in the exhibition’s finale piece, in a film wherein the director Leonardo Van Dijl gathers a collection of perspectives, interviewing ‘girls’ aged nine through to 80 about how they interpret and engage with girlhood. Lynch speaks further to this point, describing those she met while making Girls’ Night: “In different ways, they all [the teenagers] wanted to be seen,” she notes. “Some were naturally confident, others quiet or self-conscious, which reminded me how layered girlhood really is. Social media can make it feel like there’s one universal version of being a teenage girl, but there are so many nuances.”