© Vuyo Mabheka

From Vuyo Mabheka’s imagined childhood ‘popihuise’ to Forensic Architecture’s reconstructed Palestine, Bologna’s industrial photo biennial reimagines ‘home’

It would be wrong to describe a ‘popihuise’ as a doll’s house. You can’t buy one from a toy store, gleaming new and fully formed. The Afrikaans word refers to an impromptu game kids play in South African townships using whatever materials they can find around to fashion a makeshift home. Popihuis is the title of a project by Vuyo Mabheka, currently on show at Foto/Industria, a biennial dedicated to photography of industry and work, now open until 14 December, with 11 exhibitions across Bologna. The theme of the seventh edition is home, a theme that extends through an interlaced yet expansive curation where ‘home’ spans architecture, planning, class, gender, conflict, loss, belonging, identity, memory and fantasy.

Mabheka’s immersive installation surrounds visitors, drawing us into his inner world. Moving around as he grew up, he never felt tied to one childhood home and has scant few family photographs. While on the Of Soul and Joy training programme, he discovered documentary photography and began experimenting with a technique that blends hand-drawn scenes. Into these he places photo cut outs of himself and close relatives, directing figures (a sketch of an idealised father he never met, a cut out of his mother holding the baby she cared for far away as a domestic worker) like puppets to materialise memories that never existed for him as images.

By contrast, Looking for Palestine by Forensic Architecture rebuilds a visual history of Palestine that has been destroyed and denied. Their ‘memory maps’ printed on fabric represent Palestinian villages wiped from cartographic records but recovered through interviews with descendants of those villagers and resurrected using computer generated imaging software. Along the walls, archival aerial photographs reveal in stages the decimation of homes that continues, as stark video footage screened across the entire back of the space – a portal to contemporary Gaza – reminds us.

Here and elsewhere, home is physical – land and place – but also communal – shared and divided. We see this in Prut, Matei Bejenaru’s ongoing study of communities along the banks of the Prut river between Romania and Moldova that’s become a de facto border of the European Union. It’s there too in Moira Ricci’s folklore-inflected portrait of the Maremma region, where the artist’s roots run deep. And in self-taught antifascist photographer and factory worker Sisto Sisti’s 1935-50 documentation of daily life in a village housing employees of a chemical plant.

Several exhibitions consider the construction of housing as an architectural endeavour – where this goes right and where this goes wrong. Alejandro Cartagena’s exhibition in Palazzo Vizzani is an iteration of his Deutsche Börse-nominated book, A Small Guide to Home Ownership, on the effects of urban sprawl in northern Mexico. Images are hung from the ceiling so that visitors almost collide with them as they move through the rooms to represent the ever shifting nature of life in Latin America, Cartenaga says. Rows of identikit candy coloured buildings alongside pictures of residents carpooling – the only way to get around since transport infrastructure has not been fully considered. The work is adapted smartly, TVs showing American real estate ads standing in for the witty book design, which echoes a handbook, both hinting at US influence.

In images, a documentary and a display of snapshots from personal photo albums, Julia Gaisbacher introduces us to the opposite of this, a remarkable participatory social housing project from 1970s Austria led by architect Eilfreid Huth who worked with young families to co-design homes exactly meeting their unique needs. Many, now in old age, still live there, but funding for this approach ceased since it was so much more expensive than the usual one-size-all fits way so her work is a window onto utopia. Ursula Schultz-Dornburg’s show at the smart National Art Gallery of Bologna drives home the sheer variety of home constructions from Iraq to Russia, Georgia to Indonesia, each shaped by specific cultures and environments.

There are many neat echoes like this, subtle links between projects that make the whole feel coherent and revelatory, encouraging you to see relationships over time and space. The doll house-like cut outs in Monica Ricci’s work and the popihuis, say. Mikael Olsen and Kelly O’Brien’s shows seem on the surface to converge. Olsen had the chance to photograph two now empty homes of architect Bruno Mathsson. He made himself at home in these now desolate, unkempt buildings and while the former inhabitants’ presence persists, the resulting images of abandon are a far cry from the glossy ‘at home with’ spreads you see in the design press but say something about what’s left, the just-visible residues that linger.

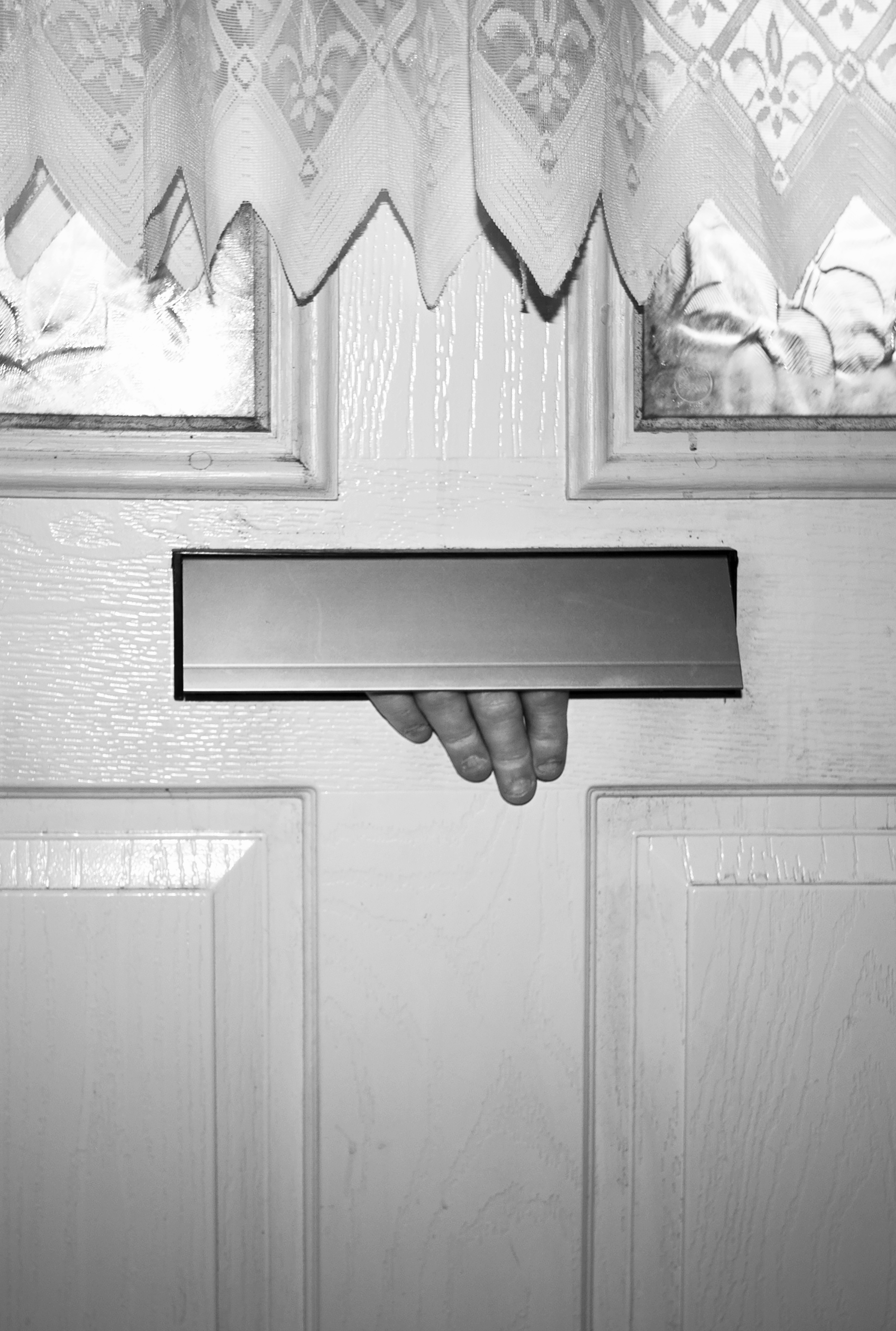

O’Brien’s No Rest For the Wicked pays tribute to the artist’s mother and grandmother, both of whom worked as cleaners in domestic settings. Their work, unlike those of an architect, is not visible, not lauded. Within a relatively small space, clever curation by Raquel Villar-Perez differentiates distinct strands to the work – earlier imagery that is more conventionally documentary alongside recent, more conceptual, collaboratively staged developments that extend out from the frame through objects and props. A portrait of the artist’s mother, with a mop obscuring her face sits on a table laid candles, a tribute to Bologna’s patron saint of cleaners.

Perhaps the least obviously related to home is LIVING, WORKING, SURVIVING by Jeff Wall, the main exhibition at Fondazione MAST, which continues until 8 March 2026. These are what Wall calls “near documentary.” He says: “I don’t have any ideas. I don’t start from ideas.” Instead, he notes a phenomenon – rural workers arriving at a city, suburban hunters, a volunteer mopping the floor – and then conjures this as he sees it. Wall invites viewers to dwell in his large-scale images. What he presents are not narratives. There is no beginning, no end, only a perpetual middle so that viewers must fill in the missing information as they see fit.

In outlining his vision, Artistic Director Francesco Zanot refers to two touchstone influences. The first a 1986 exhibition that took place in homes across a city and the second, I Like America and America Likes Me, a durational piece where German artist Joseph Beeuys lived for three days in a gallery with a coyote. Art can be somewhere we, however fleetingly, find a home. And home in turn can be a gallery, a stage, a popihuise, a place of play and possibility, risky, transformative, more layered than the everyday term would have us think. If Home is ever solid, it’s plastic, bending, in a continuous process of reconstruction, in the world and in the mind.