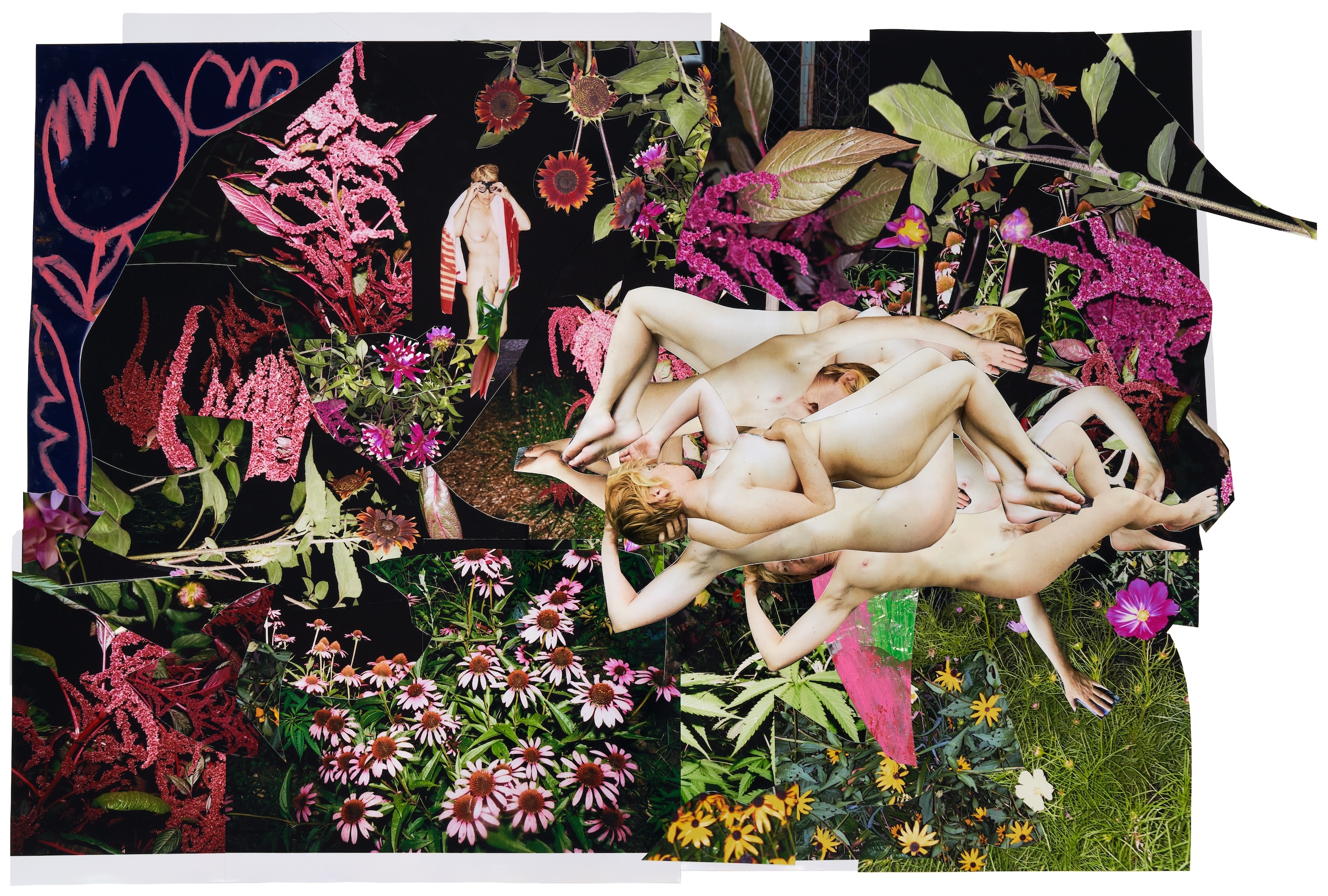

Peony, 2022 © Frida Orupabo

Cutting up the canon of photographic images gave Justine Kurland an interest in collage that has blossomed into The Rose, a celebrated exhibition on show and in print this summer

“I have been a photographer for about 30 years and in around 2019 I had this midlife crisis where I had to reckon with the fact that all my language, all the photographers who had taught me, all the books in my library, were these canonised white male photographers,” says Justine Kurland. “So I started this project called SCUMB Manifesto where I began tearing up my personal library, cutting up the images, and reauthoring them as my own collages. It was so huge, life-changing, cathartic, I can’t tell you how freeing it was, opening up a sense of possibility that we can build a new language and imagine new things.”

SCUMB Manifesto (an acronym for Society for Cutting Up Men’s Books) went on to become a success, exhibited at Higher Pictures, New York, in 2021 and published by Mack in 2022 (and nominated for the Paris Photo-Aperture Photobook Awards the same year). But, as Kurland suggests, it was much more than a work project. Collaging together the many images of women in the photographic canon suggested world-building to her, the fantasy that “everyone who was in the pictures were collaborating with me”. And her now-empty bookshelves summoned the possibility of gathering a new cohort of peers. “I suddenly had all this space for books by women, and people of colour and queer artists,” she says. “Now when I look at my bookshelves, that’s who’s here. Those are the voices I get to sing with.”

The process of creating collages felt so revolutionary that Kurland became interested in other artists using the technique, particularly other women. She started to research collage and “collage-adjacent” work from the 1960s onwards, first on her own and later with Sarah Miller Meigs and Libby Werbel from lumber room, a space for contemporary art in Portland, Oregon, which showed a group exhibition of this work in 2023. It was titled The Rose after an artwork made by Jay DeFeo from 1958–66, in which the artist layered paint and scraped it away repeatedly “until the whole thing weighed like a ton”. Including works by 40-plus artists, such as Lorna Simpson, Tarrah Krajnak, Frida Orupabo and many more – as well as The Rose itself – the exhibition was well received.

“I really want to emphasise that the curation and the editing, I didn’t do it alone. No one does anything alone”

And, like DeFeo and real roses, it also kept adding layers. Kurland, Miller Meigs and Werbel wanted to make a catalogue but, adding more artists – and realising that some of their featured artists were excellent writers – ended up creating a wider photobook, The Rose: A Circular Genealogy of Collage, which is now being published. Along with curator Marina Chao, Kurland has also put together a new version of the exhibition, now on show at CPW (AKA the Center for Photography at Woodstock, which relocated to Kingston, New York, in 2022). Chao, who was at the International Center of Photography before joining CPW, has added new artists and more ideas, says Kurland, not least the concept that, as they are constantly code-switching, women and other minoritised people live their lives as a kind of collage. “I really want to emphasise that the curation and the editing, I didn’t do it alone,” says Kurland. “No one does anything alone.”

The idea of group work runs through The Rose. Joiri Minaya’s #dominicanwomengooglesearch is included in every iteration, for example, made by the artist by quite literally searching ‘dominicanwomen’ on Google. The images that pop up show bikini-clad ladies and veer towards soft porn, a queasy sexualisation that also suggests the thin line between tourism and colonialism. Minaya blows up and cuts out body parts from these images, then invites curators to install them in 2D/3D mash-ups, in which visitors can reassemble figures if they stand in the right spot. “The instructions are just to hang the body parts so they correspond to the viewer’s body parts,” Kurland explains. “You can do whatever you want, but the head is at eye level, the torso is at torso. So not only does it deconstruct the image, it creates an analogue of virtual space, these body parts rushing at you on the interweb highway.”

Kurland was keen to engage with the sense of the body in The Rose, a perception “of how we move as we go in the world, from our internal sense of our embodied feelings to how we participate politically, culturally and societally in the world”. The exhibition also includes work by K8 Hardy that “is about sexuality and pleasure and the way we present ourselves in the world”; Kurland notes she was keen to include images in which women represent their own sexuality – rather than being commodified – because “there’s so much shame associated with it”.

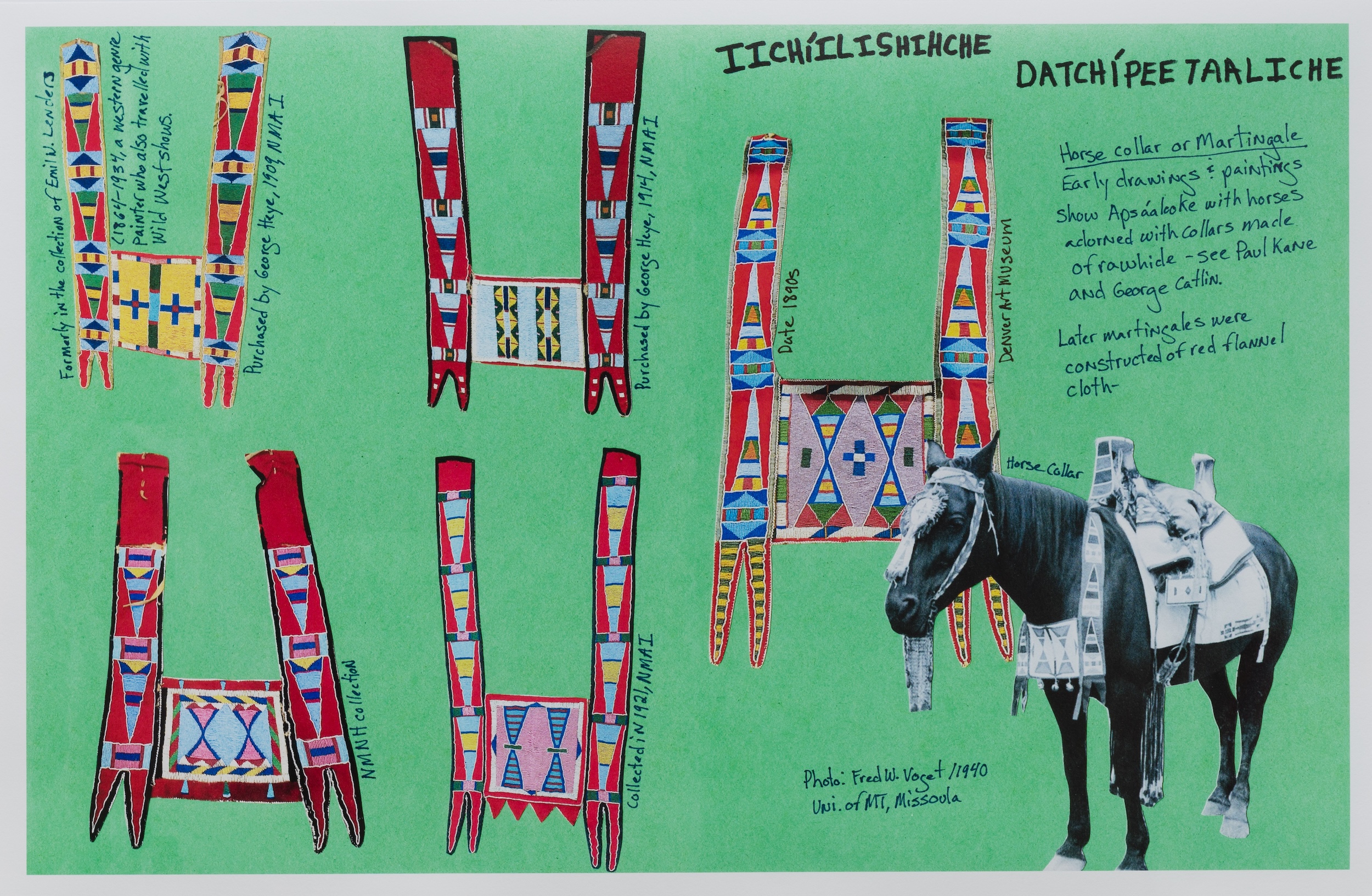

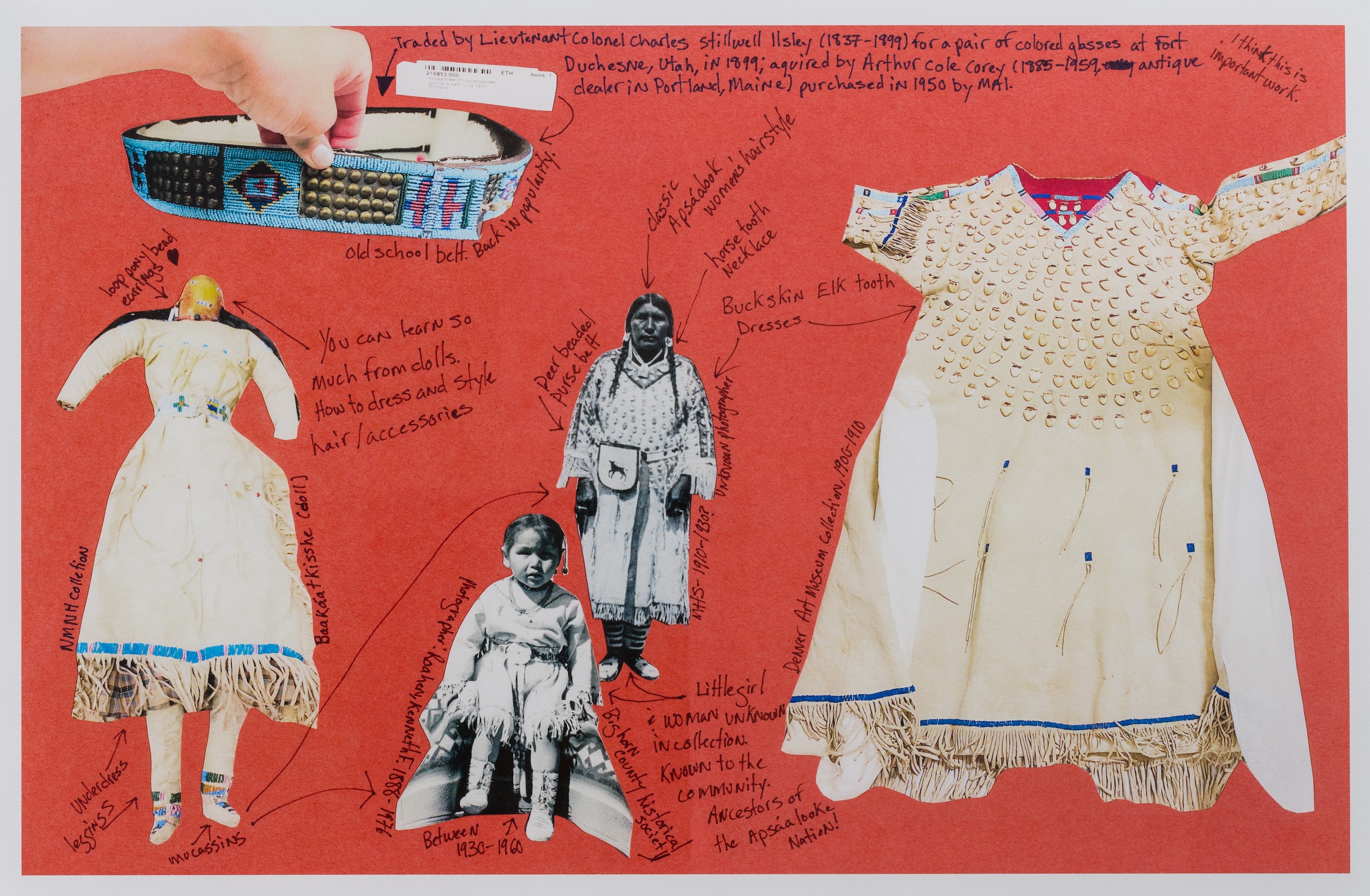

These embodied experiences also pick at the medium of photography, which represents the world via a disembodied single plane, and without engaging with other senses. This factor also flickers through the work of Wendy Red Star. An Apsáalooke multimedia artist, her collages show her community’s visual and material culture as it is formally displayed in ethnographic museums. “Since the time I left the Crow reservation I have encountered my tribe’s material culture in every city I have exhibited or occupied, and often in institutions which frequently display these historical artefacts improperly or impersonally, deprived of their context or function,” says Red Star, quoted in the book The Rose. Her collages include handwritten notes or her own hand holding objects, Kurland points out, reinserting the personal, the tactile, and the wider environment exorcised from the museum vitrines.

With this sense of the personal, and the very personal experience that kick-started The Rose, it is perhaps surprising that Kurland has not included the SCUMB Manifesto in any of its iterations. But that is a deliberate choice. “I’ve been showing my work for a long time and I have a really big platform,” she explains. “I feel very lucky about that, but it’s like in teaching – I am slowly learning to not talk so much, so that other people can feel encouraged to speak. In a collaboration or a shared space, it’s often the person who has most visibility who has to back off the most. I have already had a lot of opportunities; I don’t want to become the man I am criticising.”