Olga and Zijad © Mitar Simikić, from The Love Tales project.

The academic is based in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London but, she explains, her work centres around peace photography, what it looks like, and how it can contribute to harmony

“We all know about war photography,” says Dr Tiffany Fairey. “But why aren’t we thinking about peace photography? And how is peace photography maybe different to war photography? Obviously a lot of war photography is anti-war photography, but it’s photography in a very particular mode. It’s often about showing destruction and the damage done by war. There aren’t often many spaces for positive peace.”

Fairey is a Senior Research Fellow at King’s College London, where she is based in the Department of War Studies. But, as her comment suggests, she is much more interested in peace than conflict. Her Imaging Peace project is the first multi-country empirical study of peace photography practice, ethics and impact, and she has built on it to reach photographers and the general public as well as academics.

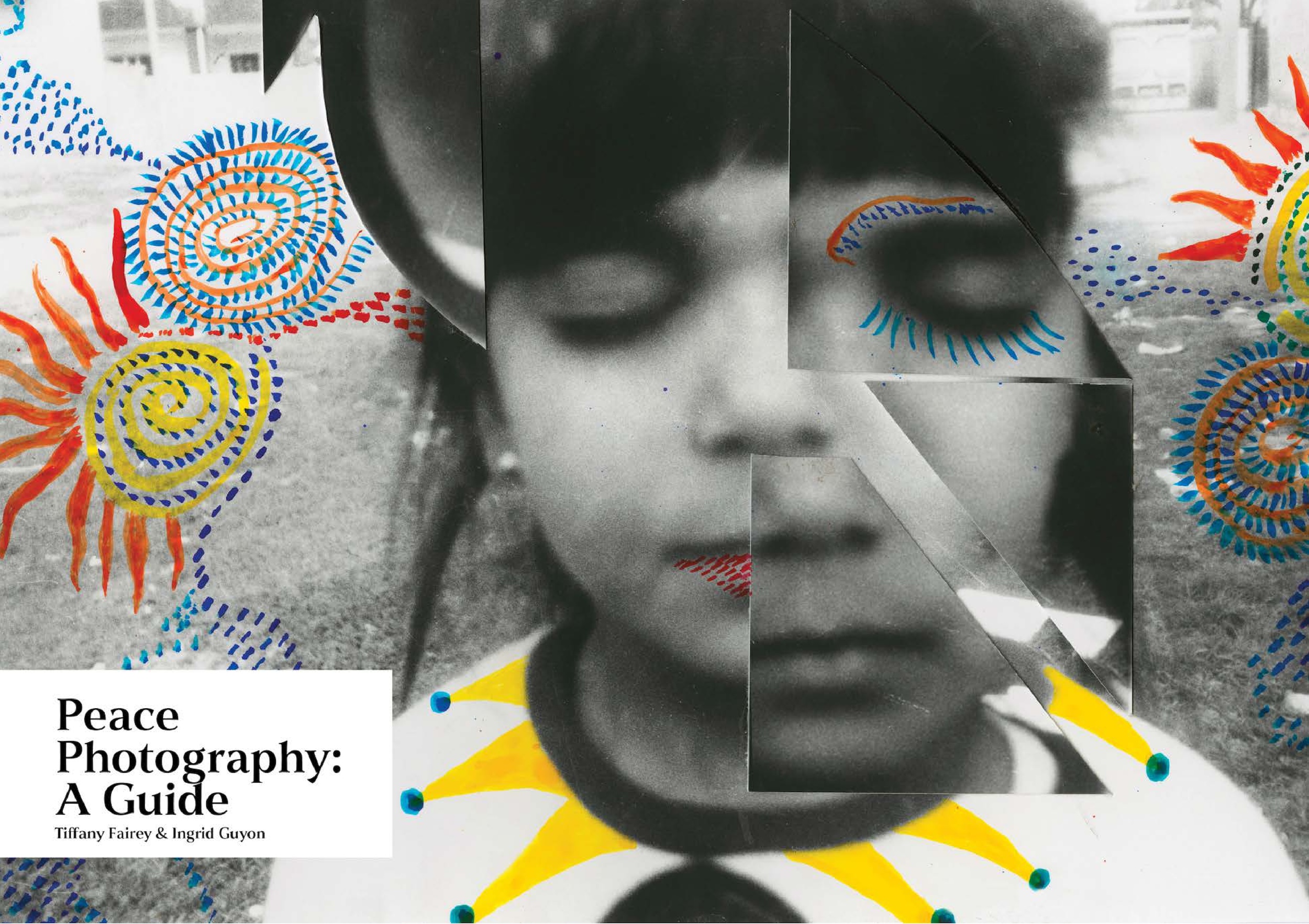

She published a free resource for image-makers earlier this year with Ingrid Guyon, for example; titled Peace Photography: A Guide and available in three languages, it offers practical tips for working with communities. She also co-curated an exhibition with King’s Culture titled Imaging Peace, on show in central London, displayed outside, and freely accessible to the public. Her more academic publication, Imaging Peace: Using Photography to Transform Conflict and Build Community, will be published in autumn with Edinburgh University Press, offering evidence-based research into using photography to help foster and maintain peace.

Brutal current conflicts have given this work a sense of urgency, but it is underpinned by meticulous research and is part of a long-term trajectory for Fairey. In 2000 she and Anna Blackman co-founded PhotoVoice, a charity promoting participatory image-making in the NGO sector, which still continues and has been active in projects all over the world. But by 2010 Fairey had realised there was a lack of research into this kind of photography, and started writing a PhD to examine different examples of participatory photography around the world.

“For indigenous groups there building peace was partly about decolonising the camera, refusing a long history where outsiders have used their image and instead creating their own”

“My whole motivation for doing the PhD was to try to build the evidence base around the impact of this kind of work, and to really think through the ethics and the politics of community-based photography,” she says.

Fairey then worked with Paul Lowe for four years, the photographer and Professor of Conflict Peace and the Image at London College of Communication; together they studied art and reconciliation, and worked with partners in Bosnia and Herzegovina such as Sarajevo’s Post-Conflict Research Centre (PCRC). Fairey’s current research draws on this background, including diverse examples which sometimes include her past projects. Peace Photography: A Guide references Side by Side, for example, a project PhotoVoice set up in 2007 to bring together Palestinian and Israeli teenagers. The guide also includes The Love Tales, an initiative in which inter-ethnic couples are depicted in images, set up by PCRC.

But Fairey’s work also includes many other case studies, carefully unpicking exactly how photography might contribute to peace; as she puts it, she is doing qualitative research at community level, to understand how communities have been working with photography. In some cases the imagery itself shows a positive example, as in the cross-community relationships of The Love Tales. But often it is the process of making the photographs which helps groups and individuals express themselves and engage in dialogue. Fairey references Sirkhane Darkroom, for example, an initiative in Turkey in which refugee children get to pick up a 6 camera, show their perspective, and have some fun.

Another case study focuses on the community projects spearheaded by Belfast Exposed, using photography as a tool to help reduce the trauma left by generations of sectarian violence. “They’re doing a lot of therapeutic photography and mental health work,” explains Fairey. “That might mean looking at the past and trying to come to terms with it. But for people with immediate issues, that also might mean doing a photowalk – being with others, learning to be in control of the things you can be in control of, and taking a beautiful photograph of a sunset. In that case photography is used as a kind of metaphor.”

In the Home Stay Exhibitions in Rwanda, a major strand of the project lies in how photographs are displayed. Mentored by Jacques Nkinzingabo and the Kigali Centre for Photography, young photographers make images, put them on show in their houses, and invite friends and neighbours to have a look. In post-conflict Rwanda, people rarely go into each others’ homes, Fairey explains, so this deceptively simple approach is ground-breaking. “Everyone is fascinated by the pictures so they come,” she smiles.

Everyday Peace Indicators in Colombia also involves exhibiting – taking images that show signs of peace in the local community, made by the local community, and putting them on show in the street. In neighbourhoods in which walls were used by armed groups to tag death threats and graffiti – and thereby exercise social control – reclaiming this space is key. “Seeing all the people looking at the photos has made such an impact on me,” comments Doña Carmen in San José de Uram, quoted in Peace Photography: A Guide.

“They look, they remember what’s happened to them, they remember the war, but they do it with tranquillity and confidence that the future is going to be better,” she continues. “In some ways, constructing historical memory is to transition towards peace. This [project] confirms the magic of this village; we needed that.”

In other cases, this initiative has had a practical impact. One community collaborated on a group photo project about its graveyard, to honour those who had been lost; this area had been neglected while the villagers focused on simply surviving. But seeing the resulting images prompted the community to clean it up, meaning the names of the deceased became legible for the first time in years. This then helped a government committee, a ‘transitional justice mechanism’, as it tried to locate Colombia’s Disappeared.

Fairey interviews and works with those involved with the projects and says doing so is key, helping gain insight into how initiatives worked, and how photography can help foster peace. Some communities have had a difficult relationship with photography because it has been – and is still – used to commodify and surveil them, she says, citing the Chiapas Photography Project in south Mexico. “For indigenous groups there building peace was partly about decolonising the camera, refusing a long history where outsiders have used their image and instead creating their own,” she says.

She also references Nkinzingabo, who points out that Rwandans have little access to images of their past, despite the many that exist. “Rwandans don’t own images of the genocide,” she says. “They were all taken by foreign photographers, so they are all owned by agencies. These are the images that are so often used to define them, so Jacques would love to access this archive, and build Rwanda’s visual history. That’s why he’s so focused on building a community of Rwandan photographers, so they can be in charge of their own visual destiny.”

Speaking with those who have experienced conflict is essential, she adds. A Google image search of ‘peace’ throws up CND signs, doves and even yoga, vague amorphous notions, as if ‘peace’ is a lifestyle choice. But for those who have experienced violence, peace is far from theoretical. They have, Fairey says, “a very keen sense of what peace is, and exactly what it looks like”.

“Many Western audiences take peace for granted,” she explains. “It’s not a tangible idea, and we’ve become so self-absorbed in terms of how peace is significant or relevant. But if you ask a community in Colombia, which is struggling day-to-day to sustain and maintain peace, it becomes very specific. Peace is, if I can go to visit my sister at 10pm without being kidnapped, peace is if our services function enough that we can get medicine, peace is knowing what happened to my disappeared brother 10 years ago. Suddenly peace becomes tangible; something about justice and being able to live a dignified life.”