All images © Zak Waters

Zak Waters traces the quiet decline of a passionate subculture — from its past to its present — capturing a vanishing way of life

Once a staple of working-class life across post-industrial Britain, pigeon racing is now a fading tradition, kept alive by a dwindling but devoted few. In Birdmen, photographer Zak Waters documents the men and communities bound by this quiet obsession — a sport built on loyalty, ritual, and deep-rooted pride. Set against the backdrop of deindustrialisation and cultural loss, Birdmen is both an homage and a eulogy: to the birds, the men, and the working-class identities that shaped them both.

Dalia Al-Dujaili: Tell me about the motivation for Birdmen.

Zak Waters: I became inspired to document the Birdmen as I remembered as a child watching batches of pigeons flying in the skies around my village. I grew up in a small working-class village in the North East of England where there was once a predominant mining workforce. A number of the men in the village unbeknownst to me were part of a Homing Society who bred, cared for and raced their pigeons. It was a 365-days-a-year pursuit. Birdmen numbers were moving towards an all-time peak. The sport was passed on from father to son like generations before them. Work was good and the Birdmen from the UK were renowned throughout the world.

So, there I was some years later in the mid 90s walking along minding my own business one spring afternoon in a rather notoriously rough area of Newcastle. In the skies above me was that familiar scene from my childhood of swarms of birds flying together in groups of twenty or more looping around the sky. I decided to investigate and followed the road to where the birds were flying from. I came across a locked gate and a heavily fortified wall. After climbing the gate, I followed a long path and came across a number of fenced gardens with several wooden huts in each plot. A few of them had men sitting outside talking, joking and calling the names of their birds as they drank tea and looked up into the skies. I knocked on one random gate and was told to come through by a broad and booming northern voice. “De ya wanna cup of tea son?” I had just entered the world of the Birdmen. This is where it began for me. Where the intrinsic camaraderie and humour of the sport became obvious. Where I could see its appeal.

“Pigeon racing is all about love. For the men, it is the love of the sport and for the pigeons, the love of each other and of home”

DA: How did deindustrialisation affect this sport?

The 1990s was a different world for the Birdmen to what I had witnessed in my youth. Within a matter of years, from an all-time high of approximately over 130,000 members and approximately 2,000 separate clubs, the number of registered racers fell to under 60,000. The 1980s had been a pivotal era for the Birdmen as heavy industry was on the decline, the coal miners had fought in vain the government for their jobs, and the ship yard industry had long since peaked.

Heavy industry was a significant factor in the decline of the Birdmen’s numbers. The winding down and eventual collapse of major industries, including coal mining, shipbuilding and repair, and steel making.

Whole communities, all over the United Kingdom, were affected by enormous economic and social difficulties. Skilled men, whose families for generations had been in employment, were faced with redundancy, job lay-offs and the prospect of lower paid non-skilled work. This led to high unemployment, debt and relocations, not just within the UK, but also around the world.

Communities were in turmoil and so were the Birdmen. I was a witness to the economic carnage of Thatcher’s Britain. I watched, throughout my childhood and early teens, people stripped of their identities and dignity as their world was torn apart by the economic downturn that took away everything.

Pigeon racing is all about love. For the men, it is the love of the sport and for the pigeons, the love of each other and of home. Two pigeons once paired will stay with each other for life, which is why, when a bird is released at a point 600 miles from its home, it will strive to be back beside its partner, often achieving this in under twelve hours. The Birdmen’s success in pairing compatible birds together, as well as keeping them fit and healthy, is the key to producing a successful racing pigeon.

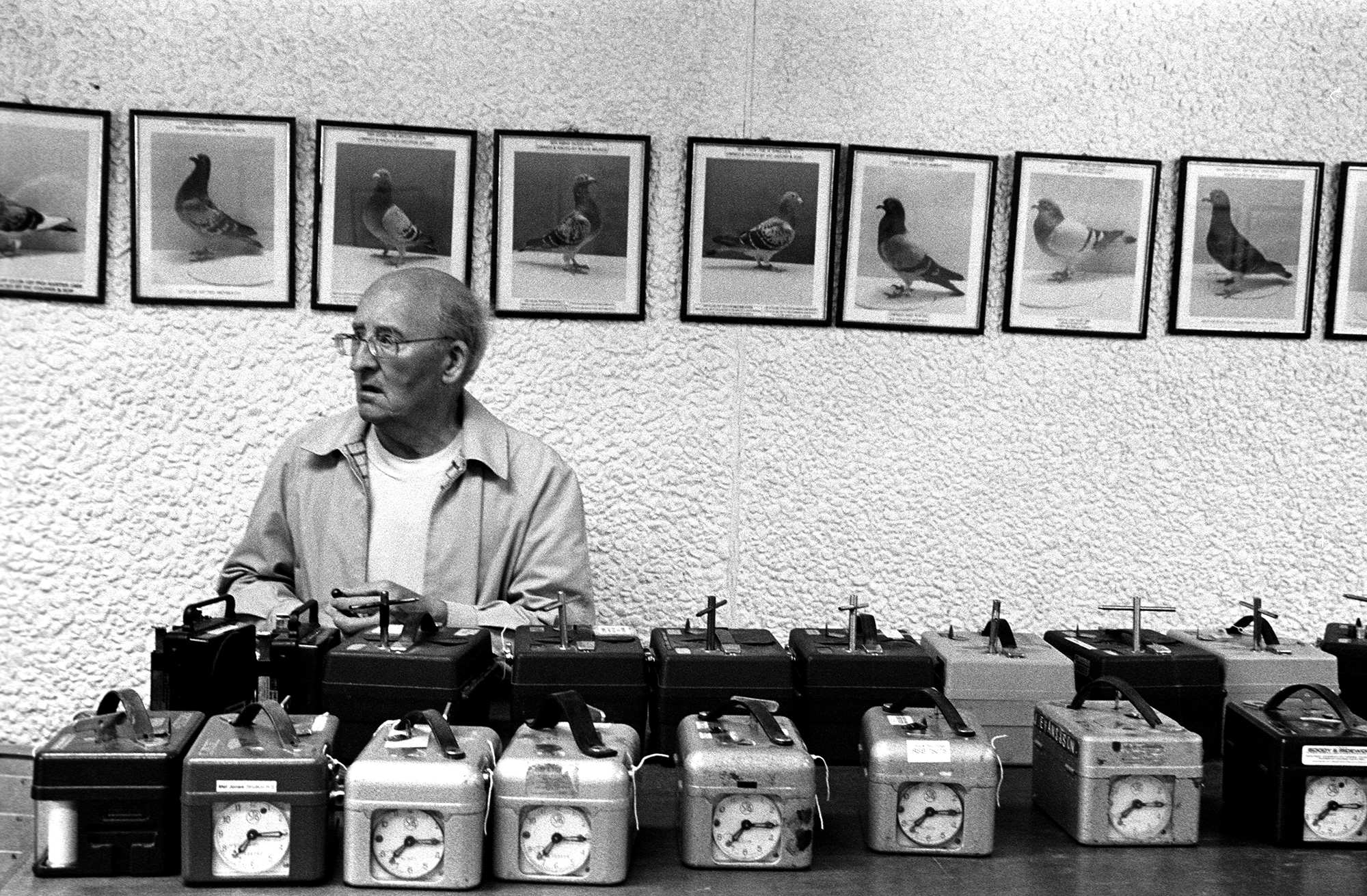

The racing season starts in April, racing their old birds and ends in September with them racing their young birds. Normally the birds are picked up on a Friday evening after the Birdmen have selected and then registered their birds at their own clubhouse. The traditional method of timing racing pigeons involves rubber rings with unique identification numbers and a specially designed pigeon timing-clock. The ring is attached around the bird’s leg before being sent to race. The serial number is recorded, the timing clock is set and sealed, and the bird carries the ring home.

Their birds are then taken by basket to a transporter and transported overnight to the chosen race venue, to be liberated the following morning, depending on the weather. The race distance can vary from 150 miles within the mainland to a cross-channel race in France, Belgium or as far as Spain.

Once the birds are liberated, the race has begun and the birds begin their journey home where their anxious owners who are hoping that their birds not only survive the journey, but also get back to their loft before their rivals.

When the first bird returns, the Birdmen remove the ring and place it in a slot in their timing clock that records the return time of the bird. From this time-stamp an average speed is measured and a winner of the race can be found.

The Birdmen run a number of betting systems within their individual clubs, but the credibility of winning far outweighs any prize winnings. The Birdmen are the last of a working class breed, through whom you can chart not only the decline of traditional industries in the UK, but changes in the life of a community that is fast becoming lost forever.

DA: What did you learn about pigeon racing during your time shooting the project?

ZW: I learned that pigeon racing is far more complex and emotional than I’d ever imagined. It’s not just about sending birds off and waiting for them to return — it’s about breeding, training, lineage, weather, instinct, and a deep connection between the fancier and the bird. There’s a quiet poetry to it. I also learned how precarious its future is: clubs are shutting, membership is ageing, and the infrastructure that once supported the sport is disappearing as well, feeding and looking after the welfare of the birds is becoming increasingly more expensive. And yet, the dedication of the remaining Birdmen is unwavering.

DA: How does the activity intersect with class and the working-class community in England?

ZW: The decline of pigeon racing closely mirrors the deindustrialisation of England as coal mines and ship building were wound down around the 90s. Entire communities lost not only jobs but the social fabric that supported the sport. My major focus with the project was on the northeast of England from Sunderland to Yorkshire as well as Sheffield and around the Wirral area to Birkenhead. I felt these areas and communities really mirrored that decline. As well as these I documented several Birdmen communities in the London and southeast area where the average age in some of these clubs was around 65 years plus at the time. I knew then that some of these clubs and men I was spending time with would not exists in a few years. Documenting it felt like photographing something on the brink — a culture that says a lot about identity, pride, and the slow unravelling of certain traditional ways of life.

DA: Tell me about how Birdmen fits into your wider work more generally.

ZW: I was brought up in a small working-class community in the Sunderland area even then I was intrigued by the people around me which led me to pick up a camera. I was always intrigued by things that might seem mundane on the surface but carry deep personal and communal significance. I think this is how Birdmen evolved. I was interested in how people shape their environments and how traditions, even quiet or niche ones, act as anchors.

Growing up around a mining community I certainly felt and witnessed this loss as a youngster. In general, I am drawn to other photographers’ projects that have social and historical weight but aren’t always seen as ‘important’ in the conventional sense. By investigating how others are creating these narratives I have been exploring concepts that follow a similar historical concept, but for me I have been researching how to present new project ideas using a more transmedia approach.

Back in the day, in the 90s I began documenting fanatical football supporters who were obsessed with their football club, but also a group of fanatics who were obsessed with just going to as many different football grounds as they could to just basically tick them off, although the more they visited different grounds they became obsessed with certain rituals whilst they were attending. I was fascinated by this extremist behaviour, their commitment and passion.

DA: What are you working on at the moment?

ZW: Audio visual has been an important step for me. As well as trying to expand ways of creating documentary visuals, I have been exploring the integration of sound as a documentary tool, adding a further layer of immersion to the photographic image. My view at the minute is to keep practicing this, make lots of mistakes which I certainly have, and keep trying to find the right unique subject matter and story line.

I plan to revisit Birdmen and collect stories and anecdotes from the last of the remaining Birdmen communities. So, when I finally launch the Birdmen exhibition in the UK, my plan is that the final exhibition will be an audio-visual experience. I think it is important that you can listen to the sounds of the men and women’s voices as they talk about their community life around the sport.