Haywood Magee. Caribbean immigrants arrive at Victoria Station, London, after their journey from Southampton Docks, 1956. © Haywood Magee / Getty Images

Fenix is a new art museum dedicated to the theme of migration – their inaugural exhibition is a contemporary spin on a legacy show

Fenix, the recently-opened museum along Rotterdam’s city harbour, focuses on both stories and visuals of migration. It is no coincidence that the enormous building in which it is housed formerly served as the departure and entry point for millions of emigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Amongst the museum’s three debut exhibitions, The Family of Migrants is directly inspired by The Family of Man, the infamous 1955 photography show overseen by photographer and curator Edward Steichen at the MoMA. Its aim was “celebrating the universal aspects of the human experience”; it toured the world for eight years, drawing millions of visitors. Instead of being structured from birth to death – as the original did – the Dutch exhibition chronicles departure, travel and arrival. The original images were pasted on wooden panels – no frames, no glass, no picture mount – and The Family of Migrants does a “more modern take on it,” per Hanneke Mantel, head of exhibitions and collections at Fenix and curator of The Family of Migrants. The museum has custom-designed aluminum frames, fitting around the photograph to the millimeter: the striking hanging of ceiling-suspended photographs and large-scale images printed onto fabric near 200 in total.

Cumulatively, they explore human movement – voluntary and involuntary – and the anguish, doubt, and hope that underpins uncertain journeys. “The aim was to remove all barriers… that could make you feel like [you’re] looking at an object or an artwork,” Mantel explains. “The most important thing in the selection has been to tell this human story and to make sure visitors have a connection with the people in the photos.”

“The most important thing in the selection has been to tell this human story and to make sure visitors have a connection with the people in the photos”

Of the photographers represented, notable names include Ruth Orkin, Ernest Cole, Alfred Steiglitz, Lisette Model, and Fouad Elkoury. The timeline is bracketed from 1905 to 2025, drawing upon documentary images, portraits and photojournalism from archives, museum collections, and newspapers. The images are not chronologically or regionally themed, pointing to the collective nature of crisis and promise.

Mantel notes: “You want to highlight the human desire to be safe or to be happy or to seek fortune – how things like that are really, at the core, the same.” Having said that, she clarifies that universalism only goes so far: “You don’t want to pretend like one person stepping onto a boat is the same thing as another person stepping onto a boat, because there are individual circumstances.”

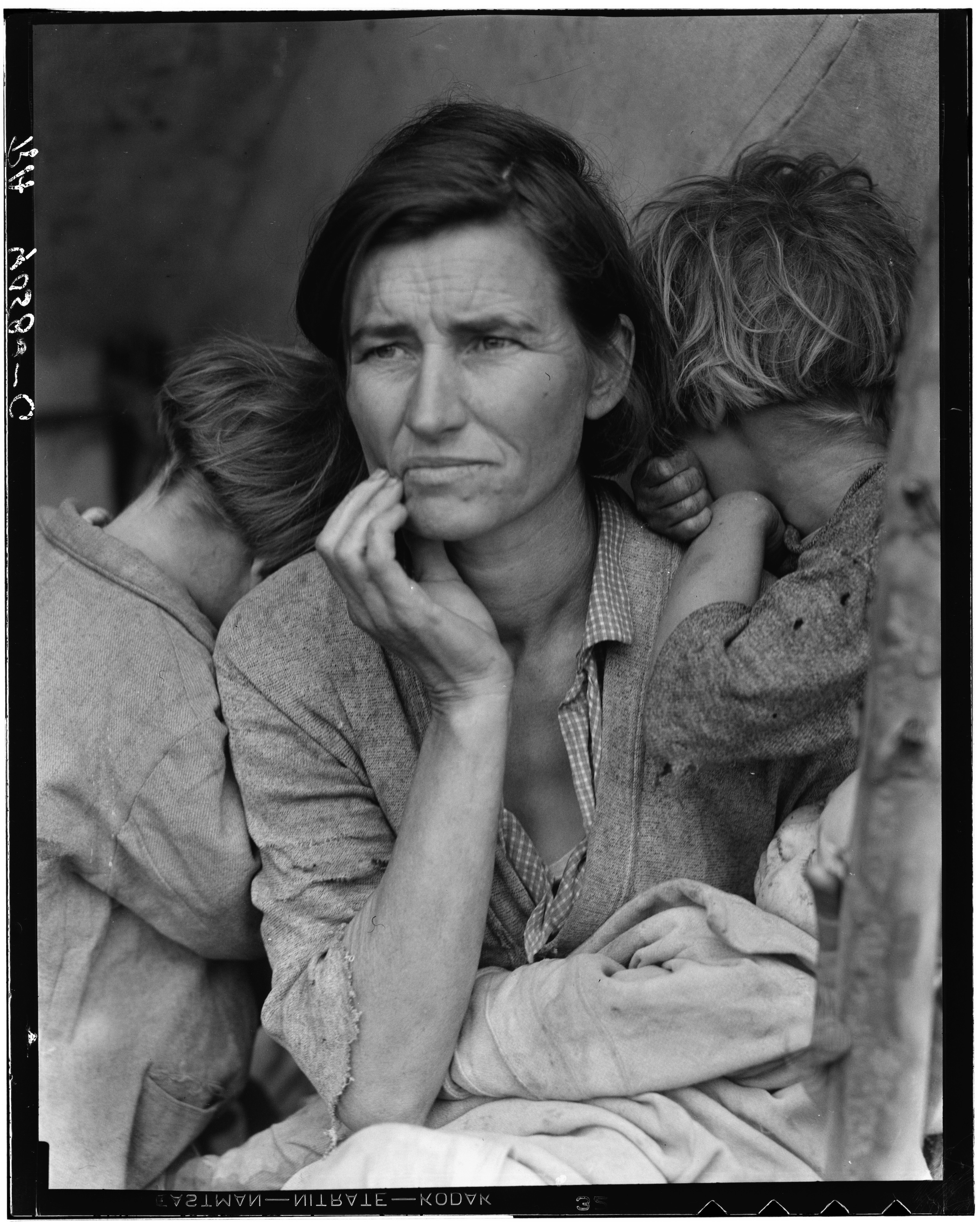

A few of the images are recognisable ones – like Dorothea Lange’s 1936 pea-picking mother and Steve McCurry’s 1984 twelve-year-old Afghan girl with the intense gaze – which are so culturally omnipresent that they have lost some of their power. The images that are most effectively unsettling reveal stories the viewer might not have encountered before, highlighting – by contradistinction – how many risky crossings go untold, unseen. “There are a lot of visual stereotypes, and you see them again and again and again and again. If you are not very, very careful, your entire exhibition is filled with those types, because they are the photos that are very readily available,” Mantel says. “We have included some of those visual stereotypes, because they have shaped the way we look at migration. They’re so often seen in the news that they are very important to humankind. However, we’ve combined those photographs with other perspectives.”

There are images of irrepressible connection, despite circumstances conspiring for rupture. There’s a photograph by Guy Le Querrec of a couple in East Germany kissing atop the wall in 1989 after it has fallen, their legs dangling over graffiti that reads ‘FUCK OFF’. Across the world, Wang Fuchun photographs a man and woman in China in 2007 whose hands meet on either side of a train window – they’re each on mobile phones speaking through the barrier – connected as closely as one can be before the journey separates them.

In a beautiful image from 1956 by Haywood Magee, a Black man facing the camera, having sailed from the Caribbean, is seen amidst a crowd at Victoria Station in London, his gaze full of hope and anticipation. His face radiates the optimism inherent in why people hazard relocation. Of course, for many, relocation is not a choice. The exhibition features images of refugees fleeing the Spanish Civil War by ship in 1936, and German Jews rejected by North American countries and forced to return to Europe in 1939. There are images depicting forcibly displaced Bulgarian Muslims in the 1980s or refugees who fled the civil war in Libya in 2013. There’s a photo of the first Syrians returning after the fall of Assad in 2025. Illvy Njiokiktjien’s 2022 photograph in Ukraine feels especially crushing: A 21-year-old woman, her face crumpled in sadness, clasps the hand of her 20-year-old boyfriend, a soldier crouched in the doorway of a train in Kramatorsk leaving to fight Russia.

It is one of many images evoking great distress. Alex Webb’s 1979 photograph of two Mexican men being frisked – their hands up in surrender as US border guards grab their chest or waist – jarringly occurs within a field of pretty yellow flowers. Though the border-crossing arrest dates from almost half a century ago, it is chillingly resonant with America’s contemporary draconian policies. Moreover, the impassivity of nature in the photo contrasts with the policing of human mobility and arbitrary imposed perimeters.

This sense of risk is highlighted elsewhere in the exhibition. Photographed by Sergey Ponomarev in Croatia in 2015, a man is seen pressed to the side of a train headed to Zagreb. His own hand is urgently gripping the vehicle while hands from inside the train help hold him in place, his jeans slipping down from the strain of his position. His desperation is tangible through his wayward body language and the evident danger of clinging to the exterior of a moving vehicle.

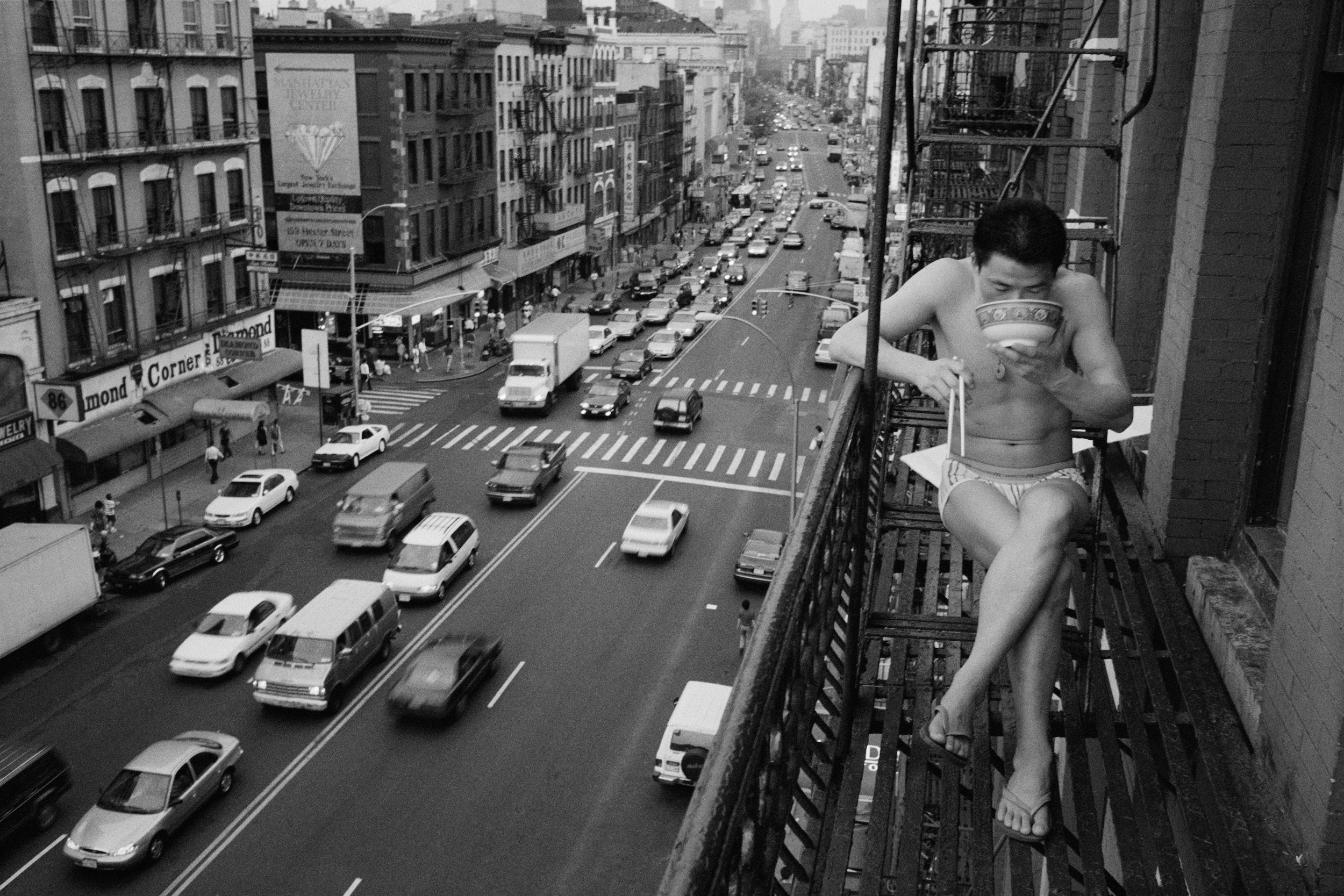

In a more quotidian but no less affecting scene, photographed by Chien-Chi Chang in the US in 1989, a ten-year-old Japanese child with a blunt bob and bangs looks acutely panicked as her white classmates pledge allegiance, hands on hearts, all around her in a classroom setting. It speaks to the code-switching expected of immigrants, of the anticipated assimilation for those whose norms were not shaped by where they live. Chien-Chi Chang further illustrates the ambivalence of adapting in another photograph, snapped nine years later: a man in his underwear sips a bowl of noodle soup on a fire escape, high above traffic. He’s honouring his heritage through his cuisine, creating a private ritual in a tumultuous city. It’s a small but meaningful act of non-compliance.