©Belfast Photo Festival

Now in its fifteenth year, the UK and Ireland’s largest photographic festival is back. Belfast Photo Festival’s theme ‘Biosphere’ asks what we owe the land and what we owe each other.

This year’s festival highlights the tradition of understanding society through our relationship with the natural landscape. This is true not only for the works being exhibited, but for the environment in which the work is positioned. The city’s history with identity acts as a powerful backdrop for conversations about our relationship with place and land, and how it impacts our idea of ourselves. Within the festival itself, a large proportion of the work this year is exhibited in the Botanic Gardens. Nestled between the trees, dozens of 7-foot-tall monoliths display the work of seventeen local and international artists. People weave in and out, mud shifting beneath their feet as photographs appear from behind the trees. In striking opposition to the white cube gallery, you occupy the space together with the work rather than escaping into it.

The majority of the work in the park is from the festival’s 2025 submissions, exploring themes of people and their relationship with their surroundings. It’s unsurprising then to see a significant representation of work from the US, including the likes of Charles Ford, Constance Jaeggi O’Connor, and Jim Mangan. The Children’s Melody by Eli Durst, this year’s Spotlight Award winner, explores the idea of American individualism through the lens of children’s development. Working with young people from kindergarten to university, Durst reveals the tension between the desire to belong and the desire to find ‘who you are’, revealing how the idea of self is shaped and shifted by the groups, communities and social forces that surround us.

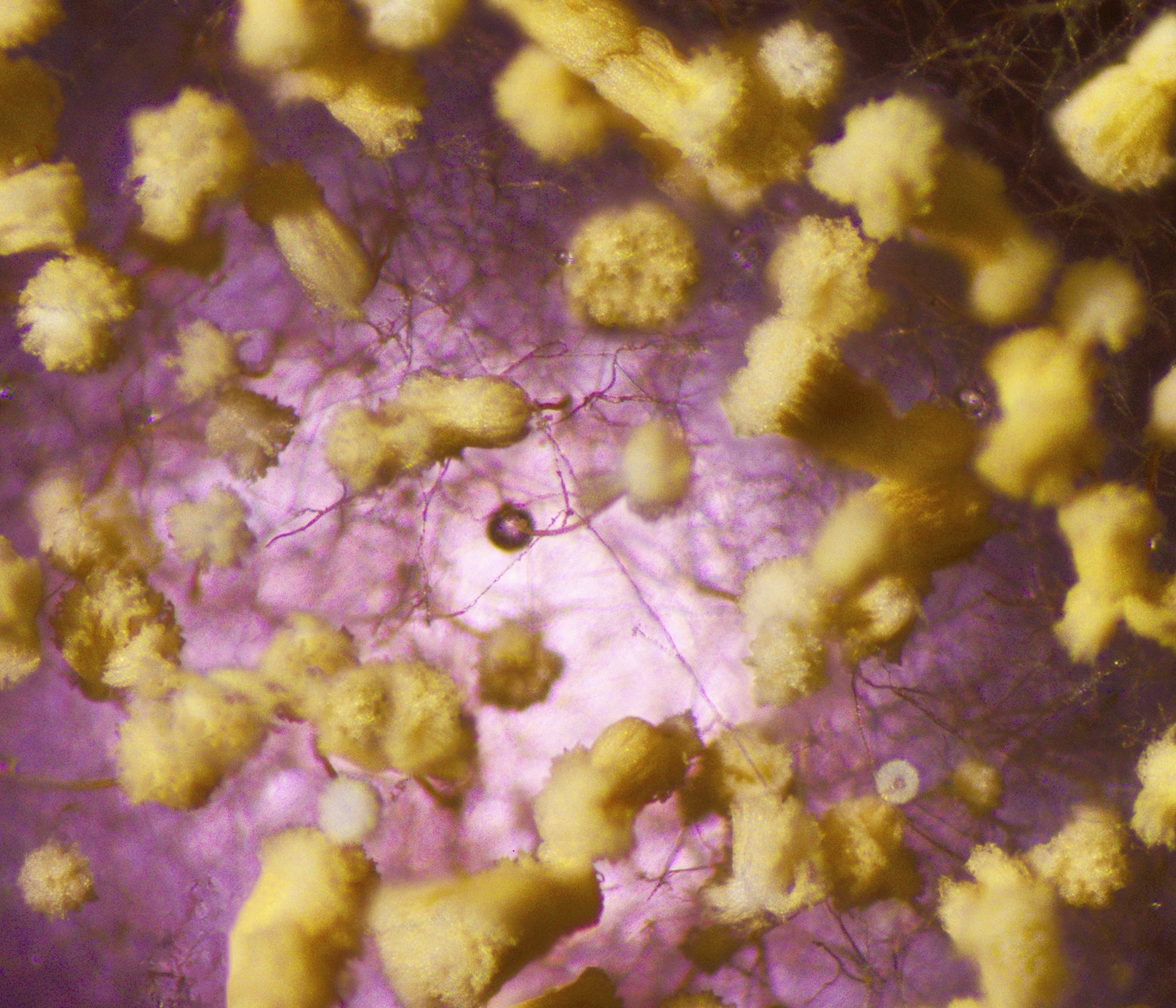

Alongside the US, Polish society, identity and ecology is a significant theme across the festival. As part of UK/Poland Season 2025 and supported by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, a collection of exhibitions titled “Metamorphosis” features the work of five polish artists considering human’s impact on their ecosystems. Anna Zagrodzka uses experimental imaging and printing methods to ask the question: how does mass murder impact the land on which it is committed? Presented on a black skeletal frame, Alternaria Alternata looks closely at the environmental microbiology that grows in the sites of the death camps of the Holocaust, investigating how the land bears witness to and reacts to signs of human disparity. Meanwhile, in a coffee shop just off the main shopping street, 0169-8629 5223-01750 investigates the environmental impact of the ongoing US military presence in an area nearby Powidzkie Lake. Using stark black and white imagery of the popular holiday spot where the photographer visited often as a child, Karol Szymkowiak expresses the uncanny juxtaposition between nostalgia and militarisation.

National identity is further explored in Belfast Exposed’s exhibition Nationhood: Memory and Hope – a group show exploring diversity across England, Northern Ireland, Wales, and Scotland. The exhibition features emerging talent across the UK, drawing inspiration from their communities to produce work about history, identity, race, gender, and religion. The heart of the exhibition is Aïda Muluneh’s latest body of work which uses their now-iconic brightly-coloured, surrealist imagery to explore the hidden stories of Bradford, Belfast, Cardiff, and Glasgow. Paying homage to community leaders, 15 black and white portraits are positioned on the back wall, like a shrine to people supporting the community at the heart of the four cities.

For the first time, the festival has collaborated with The National Lottery Heritage Fund to commission five new bodies of work visualising the natural heritage of the north of Ireland which Festival Director, Toby Smith hopes “[addresses] a crucial gap in both awareness and understanding” of these areas. The resulting work is exhibited not only across the city, but in the locations about which the work has been made. Lough Neagh, one of the largest freshwater lakes in Europe, is the focus of Joe Laverty’s work. ‘Shallow Waters’ investigates the convergence of folklore and industry in its waters. With the majority of the shoreline being on private land, Laverty brings the lake to the public with the project being displayed on digital billboards across the city and water coolers filled with algae bloom positions at exhibition venues, a stark confrontation with the pollution of the country’s primary water source.

Another project created as part of this commission series is ‘The Ocean Within’. Overlooking the Lagan river, Yvette Monahan presents a pseudo-scientific examination of marine life’s ability to map time and place. Positioned next to John Kindness’ sculpture ‘The Salmon of Knowledge’ (known locally as ‘The Big Fish’), one can’t help but to view this as an interpretation of the legend of Finn McCool – as the legend goes, McCool is granted the knowledge of the world by eating the ‘Salmon of Knowledge’. Through abstract imagery highlighting the fish’s physiology, Monahan examines the fish’s ability to map time and place within their being. It’s a celebration of fishes’ ability to ‘capture truths beyond human perception’.

Continuing with a focus on local issues and conversations, work at the Ulster Museum considers a local and often fraught relationship with land and identity with two exhibitions on the period of conflict known as The Troubles. Downstairs in a tall, echoing room, a collection of Bill Kirk’s sprawling archive of images from across Belfast and Newtonards tell the story of the era through the eyes of someone who lived it. The exhibition is part of a series curated by Frankie Quinn and The Belfast Archive Project, an organisation aiming to ‘preserve, interpret, and present [Belfast’s] vanishing photographic heritage’.

Elsewhere in the museum, Japanese photographer Akihiko Okamura’s ‘The Memory of Others’ shows moments of passing through, of before and after, rather than right in the thick of it. Instead of high contrast black and white imagery we have come to associate with this period in Irish history, soft light and colour re-establish the place and people he photographs in reality. Although we see figures synonymous with the period such as Ian Paisley, there is a focus on women, on children, and on landscape. Having seen the work in Dublin and London, this time felt different. Small groups of elderly people wandered around, pointing at images, debating about what shops are now in the place of the ones in the pictures. An exhibition about the period that felt like it was made for the people who had experienced it.

The festival’s programme and careful curation created an ecosystem in which to consider our relationship with the environment and the spaces we occupy. A careful reflection on people and place, past and present, and the forces that combine them.