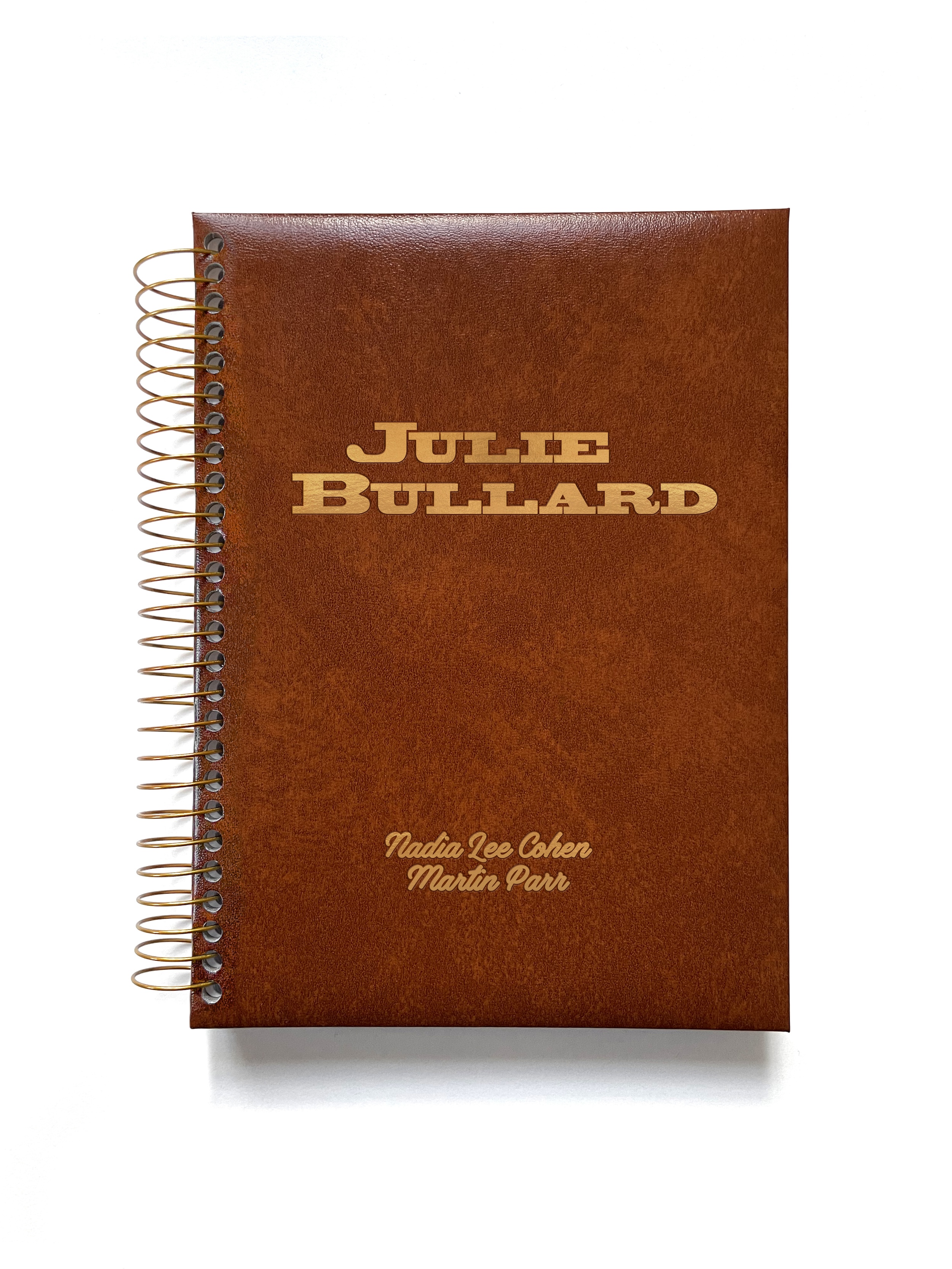

All images © Nadia Lee Cohen and Martin Parr, courtesy of IDEA Books.

Julie Bullard, inspired by Essex glam, pays homage to Cohen’s childhood babysitter, shot by her own photographic hero

Martin Parr is perhaps a little discreet when he harps on the fact that it was Nadia Lee Cohen’s script that he was following while shooting Julie Bullard. “This was inspired by Cohen’s personal experience, she made the script,” he tells me, “I would chip in when I felt it was required.” Encased between brown faux leather, is their photo book, modelled on a late seventies photo album acquired on eBay – complete with the familiar gold spiral binding. It’s a fictional account woven around Nadia’s childhood babysitter – Julie – played here by the visual artist.

“Parr does have a very clear aesthetic and that made it quite easy to anticipate the way he would photograph a situation he was confronted with,” Cohen explains. Having always wanted to be in his photographs, she invited her favourite image-maker on to this performative documentary on the life and times of a working-class woman – and he accepted.

“The 1990s and early 2000s are just indicative of my own nostalgia as those are the eras I grew up in,” Cohen reminisces. It was a time when Jodie Marsh was on Essex Wives and the Footballers’ Wives was airing on television. “That was glamour to me as a teenager.” It would be something similar on Julie, which would catch her eye as a child – her naturally blonde curly hair, which Cohen hadn’t encountered around her before – which she often sports now. Therefore, Nadia’s Julie is also blonde and smokes with an air of disillusionment as she goes about her chores – although her precocious eyes have a detached and faraway look in between moments of respite, which says she is stuck here in between her noisy twin sisters in a house of kitschy baubles.

“Humour is there because the world is pretty funny anyway”

– Martin Parr

“I told her I wasn’t getting out anyway,” Bullard writes angrily and resignedly for a photograph where she’s fighting with her mother from a car – it’s meaning perhaps more implicit than just staying in a car. Cohen treats the album as a journal, perhaps taking from Parr’s ‘Sign of the Times’ with everyone photographed speaking to us through the captions in direct speech.

It feels familiar to enter Parr’s world of brightly saturated urban kitsch in working class homes – particularly through what Parr has always highlighted raising discomfort – an obsession with consumerism. I remember when Tupperware entered the container scene when I was growing up around the noughties, how suddenly it became the tiffin box for the middle class. It’s a similar feeling looking at colourful boxes stacked on top of each other, probably bought by a door-to-door sales representative presenting to the admiring women around her – other than Julie, couldn’t care less about separate boxes for “sandwiches, soups, gravies and powders” and looks away. She also detests her grandmother’s prized and possibly cheap Murano glass replica fish – once again a fixture in most middle-class households in the 90s.

Cohen wasn’t thinking about class, and neither was Parr – she was visually portraying a song by Squeeze called Up the Junction, she says, where the guy marries a pretty girl after she gets pregnant and she leaves him acquires a drinking problem. “I was not considering this to be a class issue,” Parr urges again, “They all make good photos. We have kitsch all around us, so it’s natural to include it.” The artist Grayson Perry termed it as “finding beauty in the trashy” in the documentary ‘I Am Martin Parr’ (2024), but perhaps Bullard wouldn’t exactly agree with the beauty bit.

Julie Bullard’s aspirations are most clearly seen in a photograph of a glittery eyeshadow palette from a Chinese company Miss Rose, with pink curlers and a hair dryer which she titles Vogue. Cohen found herself changing what she thought about glamour upon spotting a copy of French Vogue during a holiday. It’s perhaps self-referential in a way, however, having a night on the town is not what Julie wants to do either – although the makeup palettes clearly imply a concern about her appearance. She purchases breast pads from Woolworth’s to make her breasts appear larger for ‘confidence’ after wearing a swimsuit. While she does feel like she is carrying Martin’s aura of being disconnected with working class surroundings, there’s also another dimension to her narrative of being yet another woman wanting a life beyond the usual life of marriage, childbearing or the Bisto gravy her mother serves in their perfect TV dinner-like meal – but ending up getting that anyway.

After an unplanned pregnancy, she is married off. Cohen cleverly never shows her husband – it may be Ashley the postman, her ideal man at five years old, but we don’t quite care about that.

An English breakfast lies before us from the café Julie has taken up work in. Parr has always been drawn towards food, like in British Food where the saccharine red and blue icing on cupcakes topped off with the British flag leaves a cloying aftertaste. It is stark and visceral, the way he photographs food, through the greasy protein of a sausage or the sickly pale green of mushy peas. “I like shooting both food and tattoos,” he says simply and then adds on a whim, “junk food makes better photos than posh food.”

Colourful food permeates the entire book in egg sandwiches, yellow cereal in yellow bowls or mini cherry Bakewell tarts – all of which is very reflective of the kitschy colours around them, and moreover, are all quite British food. It’s also a certain nationalistic kitsch that Cohen is perhaps critiquing, through a decorative plate of Charles and Diana created upon their marriage, and still hanging five years after they had divorced – a sham of an image of the perfect English couple. Cohen seems to be critiquing a certain kind of nationalism and when asked, she explains, “I’m interested in the physical manifestations of nationalism.” Therefore, Julie perhaps seems quite distant from moments of nationalistic fervour, like celebrating the England vs Germany Euro qualifiers in 2000 with someone who had his buzz cut hair painted with the British flag.

What also comes through is Martin’s sharp humour when photographing Britain, which he has termed previously as a “love-hate relationship with his homeland”. “Humour is there because the world is pretty funny anyway,” he says, “when it’s brought to your attention in the right way.”

The realisation of Julie’s death comes when she stops speaking to us through the captions. It’s almost cinematic in the way the photographs have been lined up where her face isn’t revealed to us in the very beginning. “I think it’s just a sense of a swan song, curtain drawing, ending type of thing,” Cohen says. Silence in place of Julie’s quick, sardonic humour is perhaps when we first realise, we had begun to really care for her over the past hundred pages. Cohen’s independent lens-based practice is inherently performative in her becoming characters and acting them out like in My Name Is.

“Cohen’s script was inspired by her personal experiences,” says Parr. It’s a little similar to what Parr did in Autoportrait where he took on different personalities to show the change from analogue to digital photography – although it wasn’t what he had in mind while shooting with Cohen, he says. “I was just concentrating on what was happening around me so I could make my shot,” he explains as often has. This is the first time she’s worked with a complete narrative culminating in a demise, and while the real Julie is well and alive, Julie’s death perhaps implies something deeper or at least a change in Cohen’s performative practice.