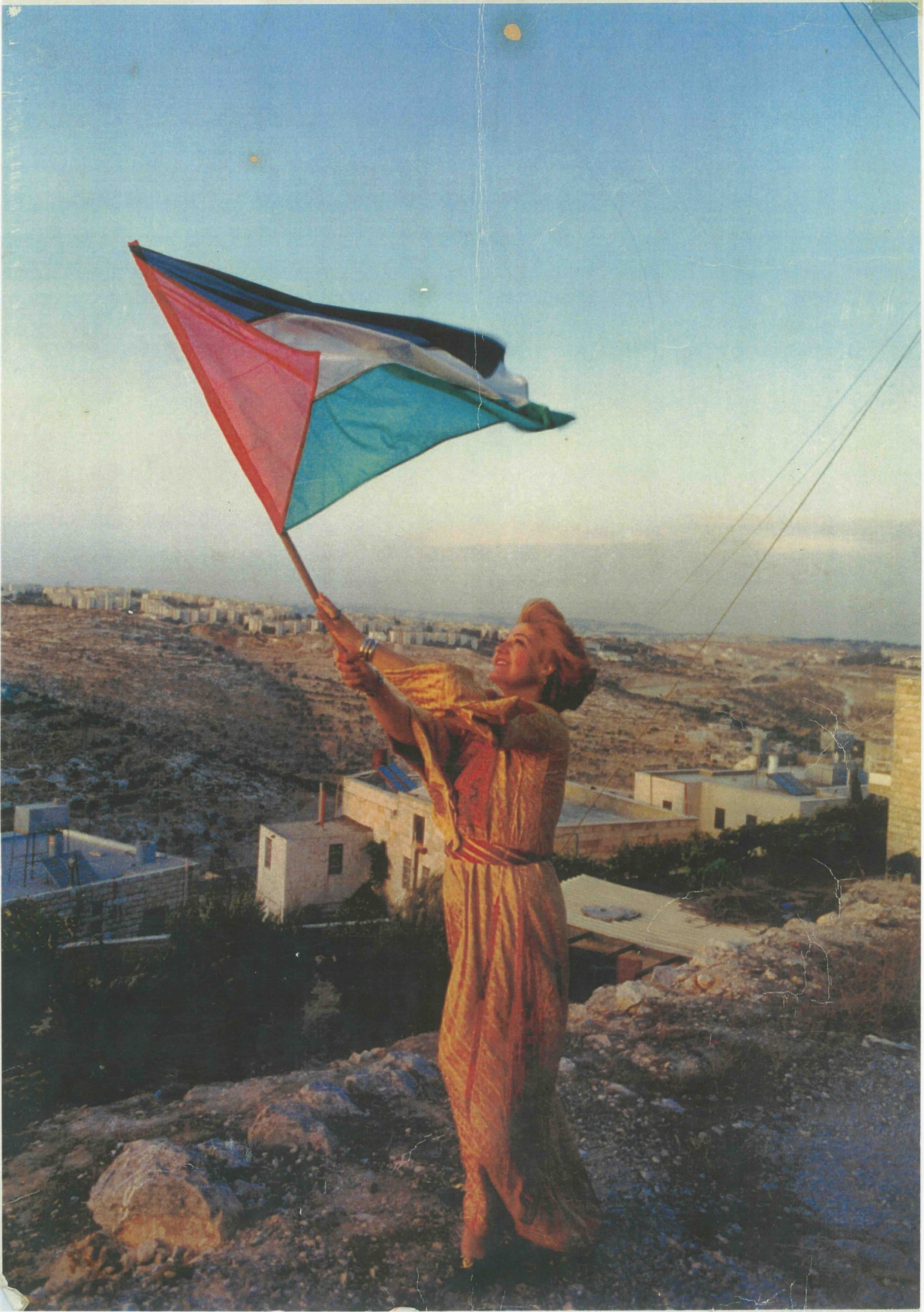

Saleem Dawood Azar, Gaza, 1985. Courtesy of the Palestinian Museum

Making use of the Palestine Museum’s large digitised collection, Rachel Dedman curates photographic context to visual heritage not “limited to colonial collections”

When Rachel Dedman first began researching tatreez, the rich tradition of Palestinian embroidery, it wasn’t with the intention of unearthing a photographic archive. But over a decade on, with the exhibition Thread Memory at Hayy Jameel in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, photography plays an unexpectedly central role. Curating images from the Palestinian Museum’s archive was “such a joy” for Dedman, she tells me. “So often in exhibitions of this kind we tend to be limited to colonial collections like the Library of Congress or the Palestine Exploration Fund, images of Palestine that are taken through colonial eyes and which reflect a colonial gaze. And what’s so remarkable about the Palestinian Museum is they’ve reached out to the global Palestinian diaspora, who are the custodians of Palestine. They’ve invited them to digitise family photographs.”

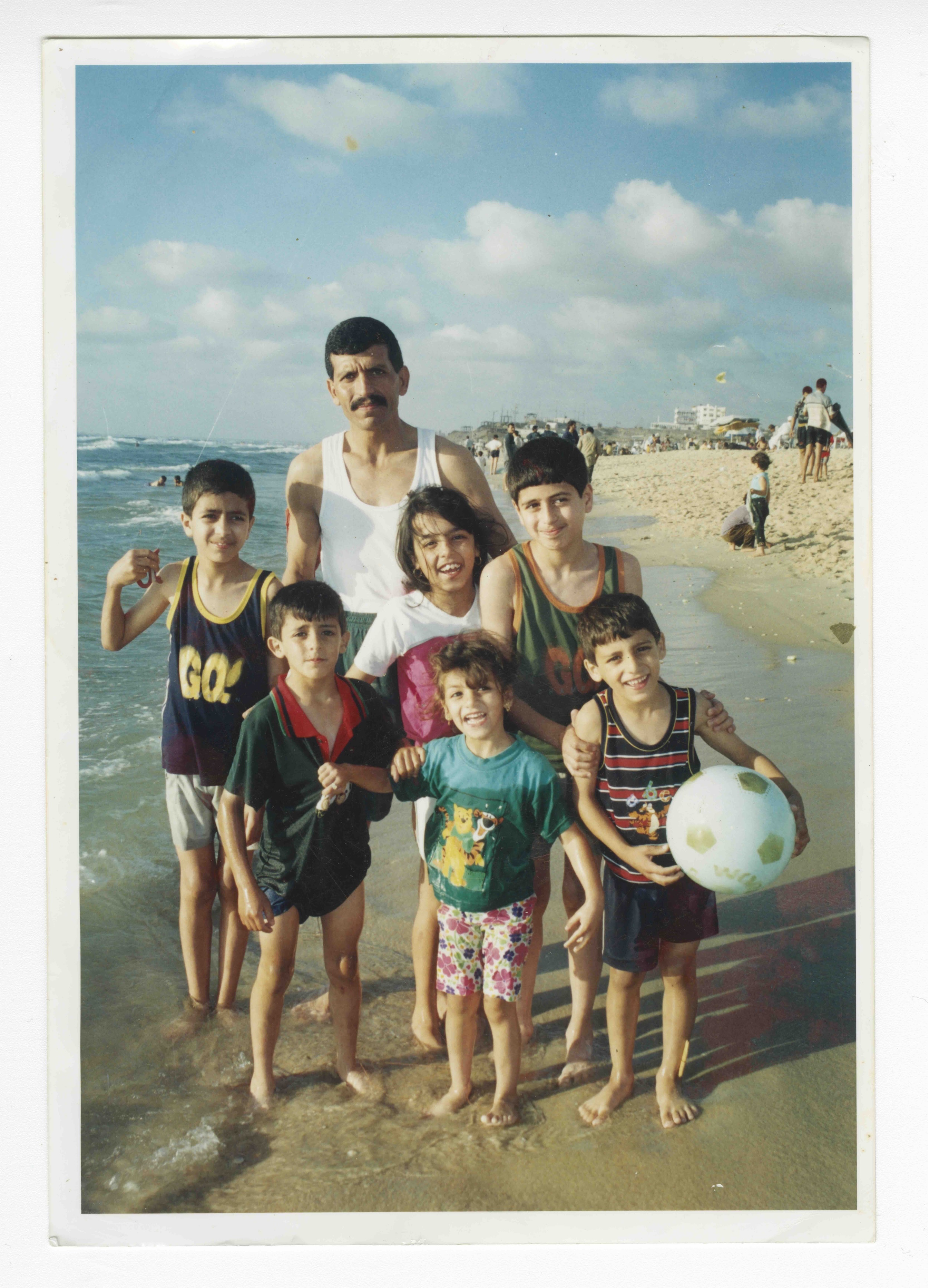

These photographs – ordinary and intimate, often blurred or sun-washed – are the connective tissue of Thread Memory. They appear alongside dresses from Saudi-Palestinian family archives and material from the Museum’s permanent collection, offering context not as a caption but as narrative. They reframe the garments – deeply embroidered maps of place, status, memory – as lived objects, worn by real women in real time. “They tie the exhibition together in giving a bigger-picture context,” Dedman says. “They give the dresses life… to de-anonymise these women. To name the people in these images, because they’re from family albums.” It’s a kind of quiet, precise refusal – of abstraction, of generalisation, of the flattening that can so often accompany heritage displays. Instead, what emerges is a portrait of Palestinian embroidery as a dynamic language, a political and a personal one.

One image, for example, titled ‘The wedding of Naifah Ashrawi’s daughter, 2001’ shows women in their tatreez gowns, plucking and tidying a bundle of roses into a bowl in a family home. We are welcomed into daily life, in this instance. The image is surrounded by six other family photographs on the wall, taken almost literally from family albums, revealing the very real and tangible role that photography and the lens play in not only preserving the memories of exiles and migrants, but in connecting diasporic peoples to their homelands.

“Tatreez is a touchstone to Palestinian national identity in political posters and imagery in the 70s and 80s”

Thread Memory is the latest version of a project that’s been unfolding since 2013, when the Palestinian Museum first invited Dedman to curate a show about tatreez. That exhibition, At the Seams, was staged in Beirut, and eventually published as a book. It was the result of months spent moving through the region – across refugee camps and villages – tracing the ways in which tatreez had operated as both craft and financial means. “I wanted to unpack the economic question around the empowerment offered by organisations,” she explains, “as well as what it means on a personal and political level.”

That collaboration focused in large part on the Museum’s digital archive – a vast resource of over 500,000 documents, many of them photographic. While tatreez is the visible thread through the show, the photographs provide a sense of social and political texture. “The show is not only immersing visitors in the heyday of tatreez in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” Dedman says, “but also extends that story beyond the Nakba of 1948 to engage the politicisation of tatreez and evolution of the craft associated with solidarity and kinship.”

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, tatreez began to appear in protest posters, political pamphlets, and exile literature as “a touchstone to national identity in political posters and imagery in the 70s and 80s,” Dedman explains. One image by Joss Dray, 1997, depicts a woman in tatreez confronting an Israeli soldier, a perfect pictorial example of the political role of embroidery, and the central role of women.

The legacy of visual symbolism carries through Thread Memory, where archival material isn’t neutral; it’s radically local. Images are drawn not from state institutions or foreign-held collections “like the Library of Congress”, notes the curator, but from families. “Palestine through Palestinian eyes,” Dedman calls it. “These are family snapshots rather than staged images which support a colonial or foreign European narrative or projected ideal of Palestine,” which humanise the women who made and wore these clothes, and locate their daughters and granddaughters today. The show ultimately says, then, that: Palestine was here and Palestine persists.

In a context where Palestinian visibility is often distorted or erased altogether, the simple act of showing someone as they were – in their own clothes, on their own land, captured by someone who knew them – becomes radical. The show also includes three mobile phones which capture the IDF’s deliberate targeting of the Rafah Museum, which was housing Palestinian heritage artefacts. The phones play out a real WhatsApp conversation and voice notes from staff on the ground in Rafah, Gaza. Though Dedman has been exploring the sartorial and cultural heritage of Gaza in many of her previous shows before 7 October 2023, the current ethnic and cultural cleansing makes Thread Memory vital, urgent and necessary.