All images © Hicham Benohoud

The photographer challenged the status quo of Moroccan education through surrealism in The Classroom, now published by Loose Joints

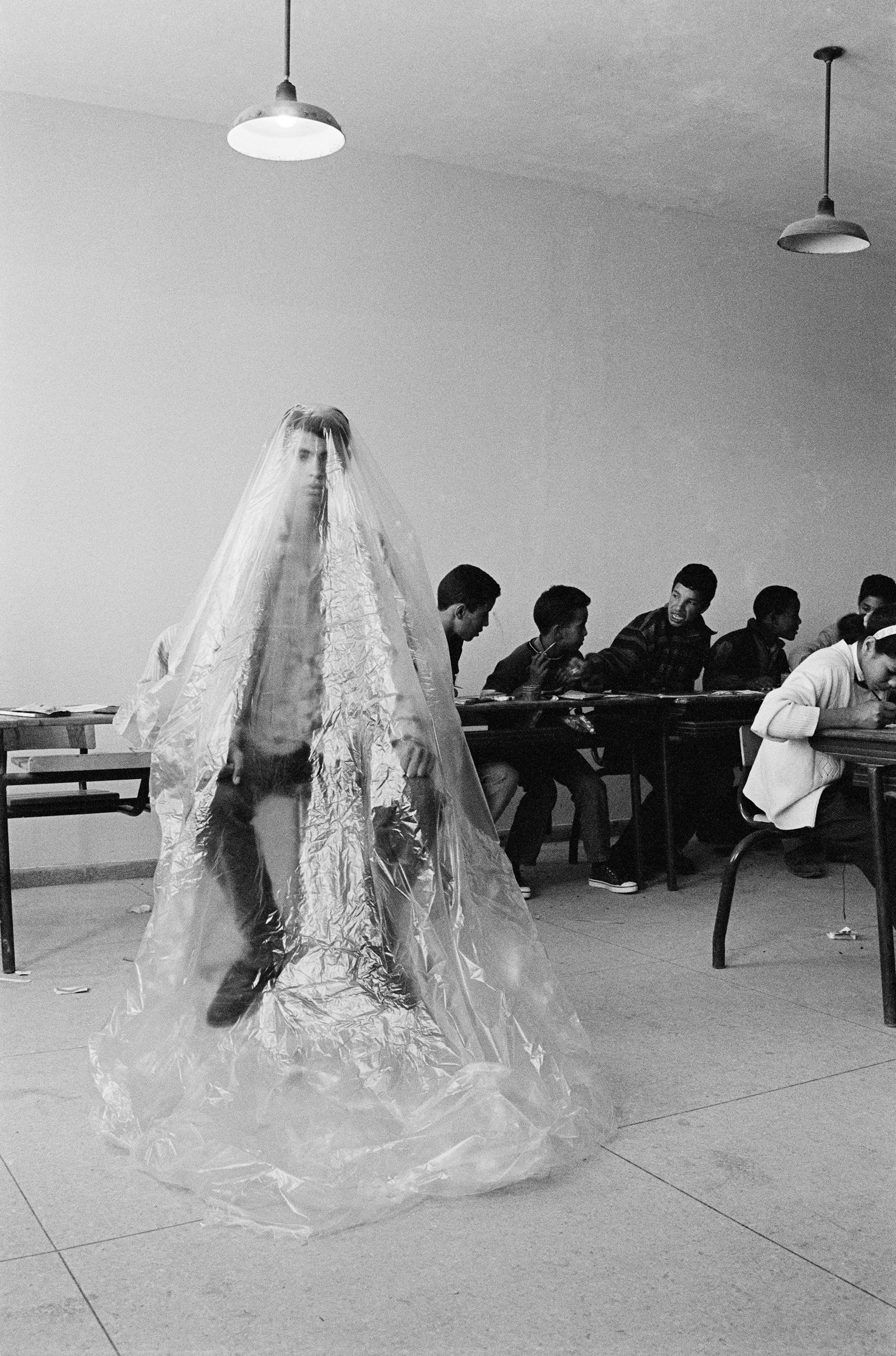

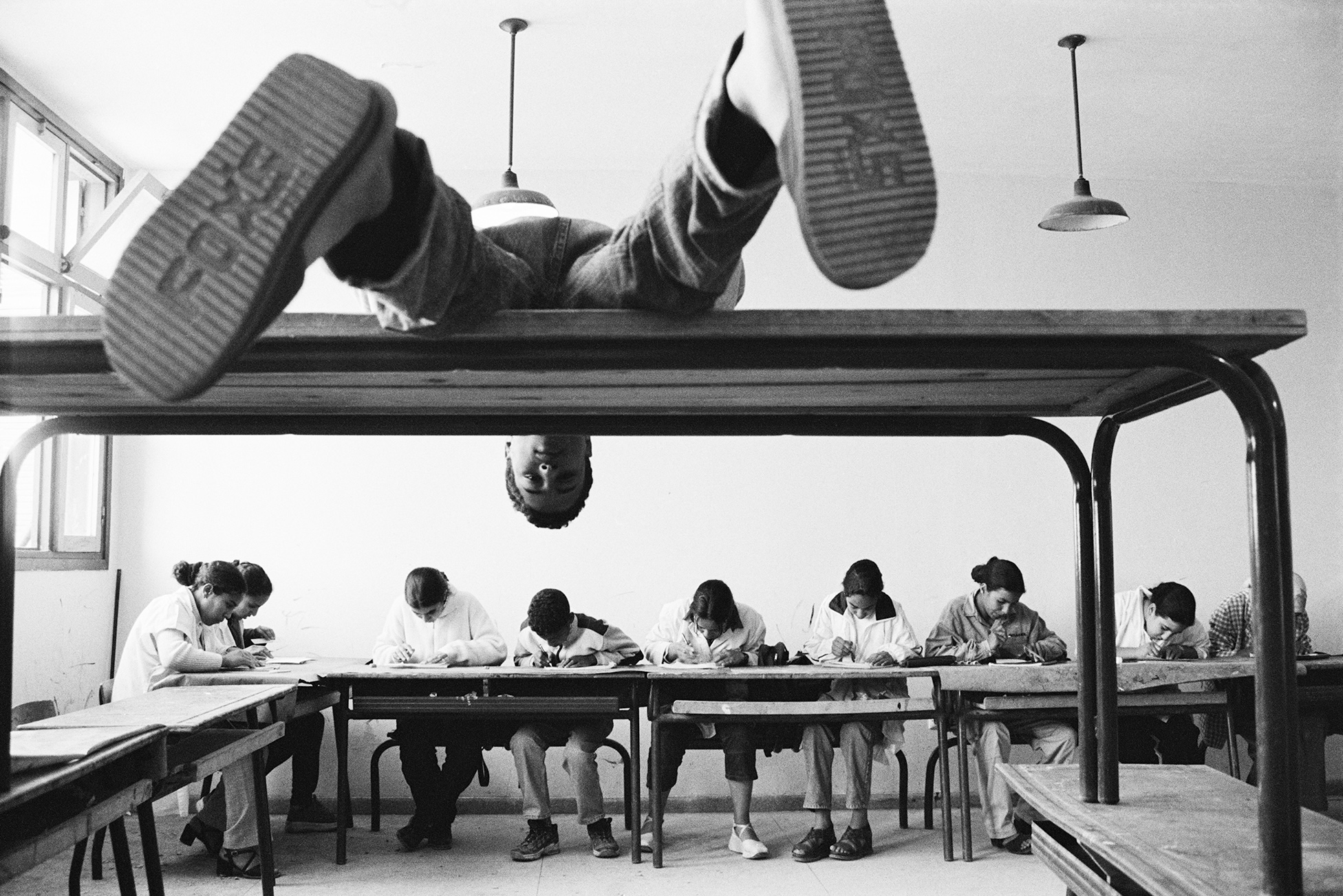

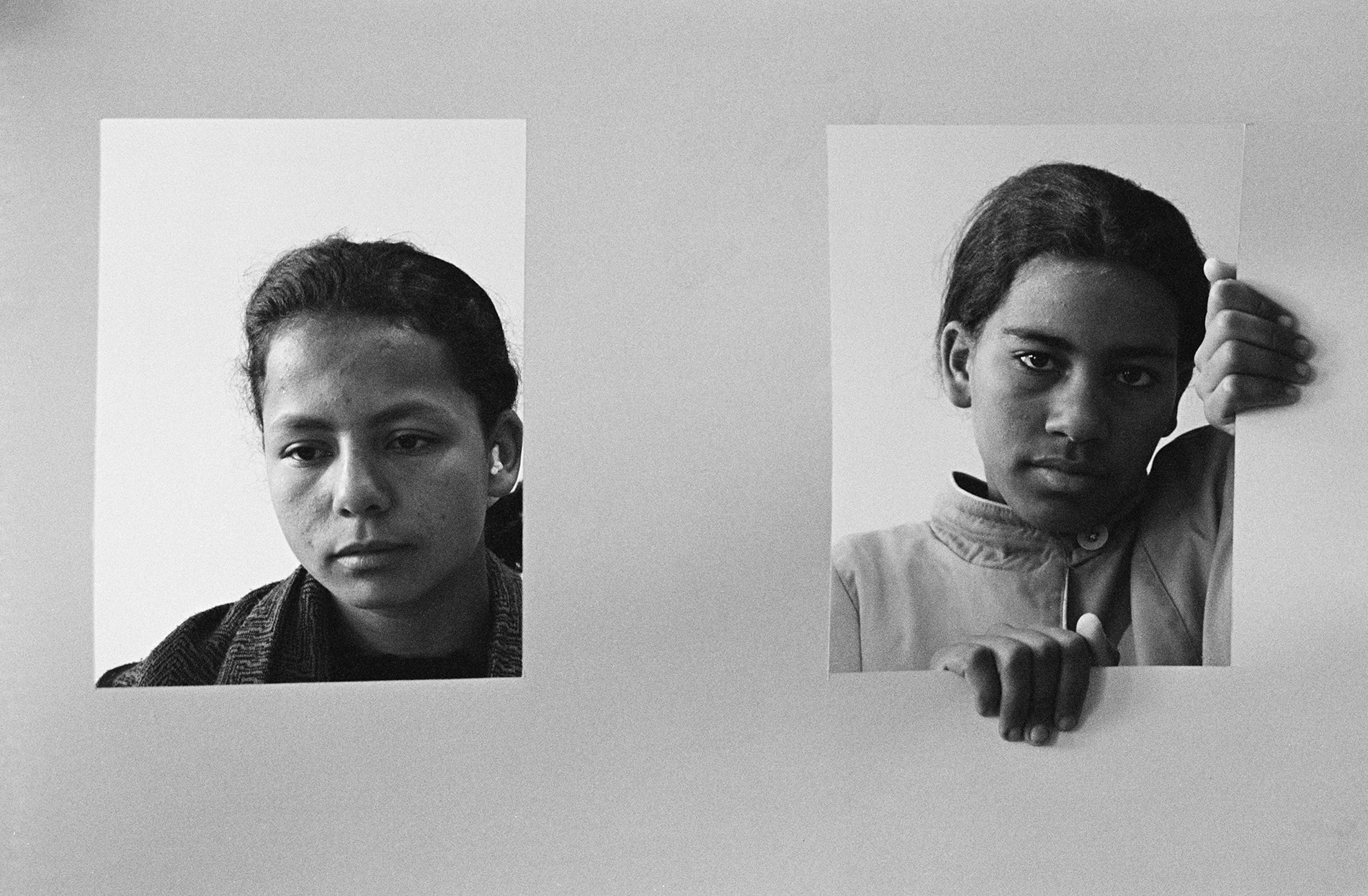

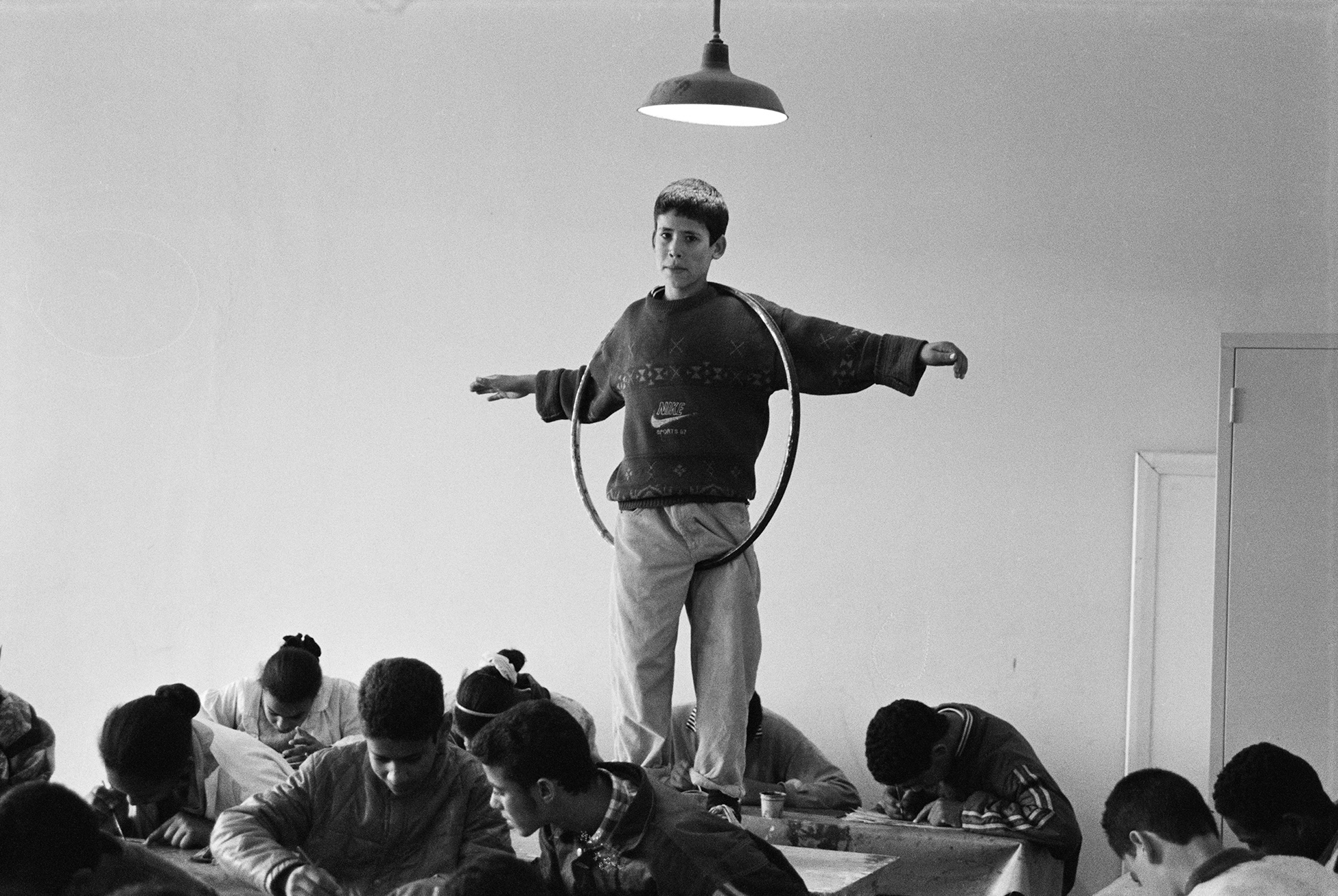

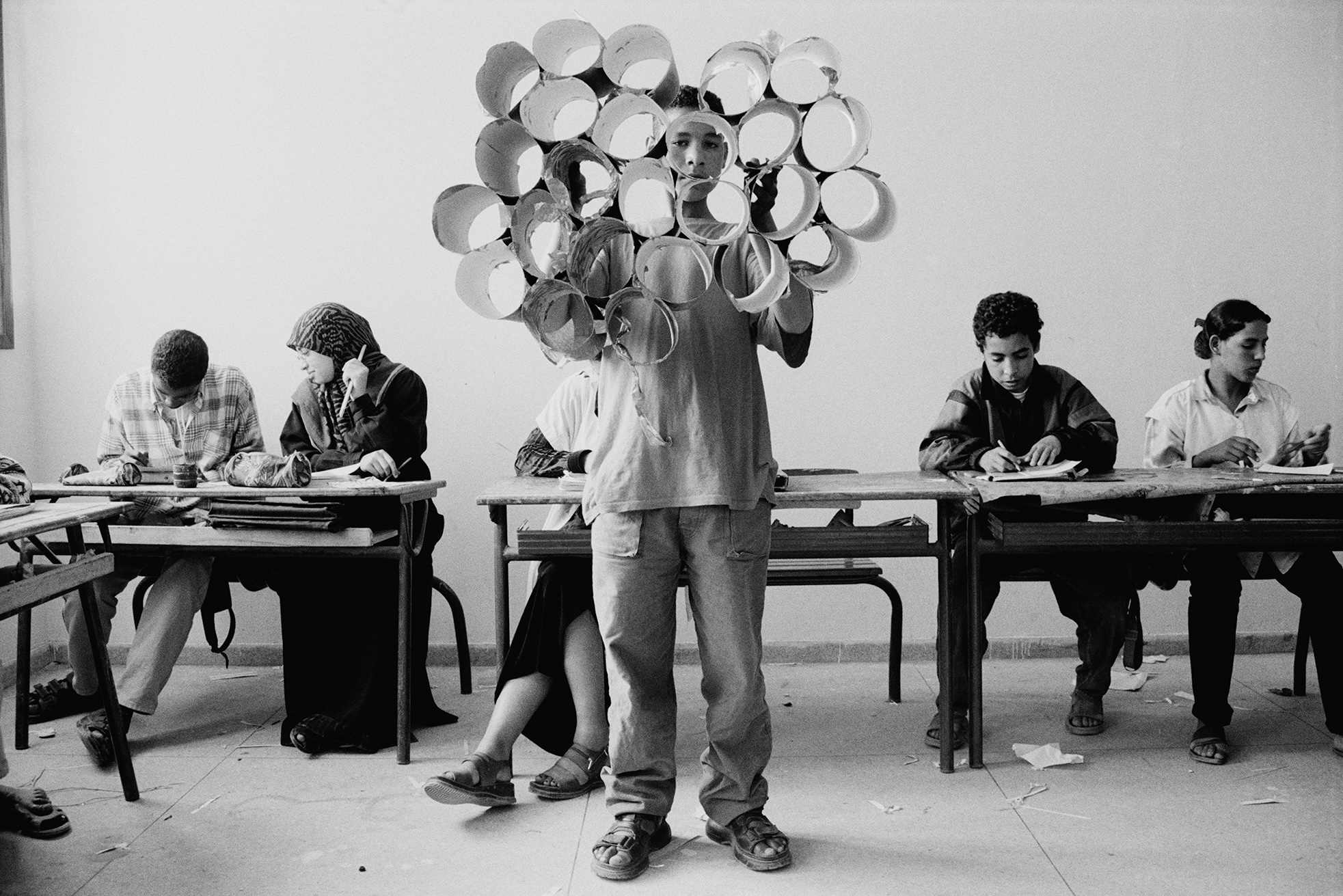

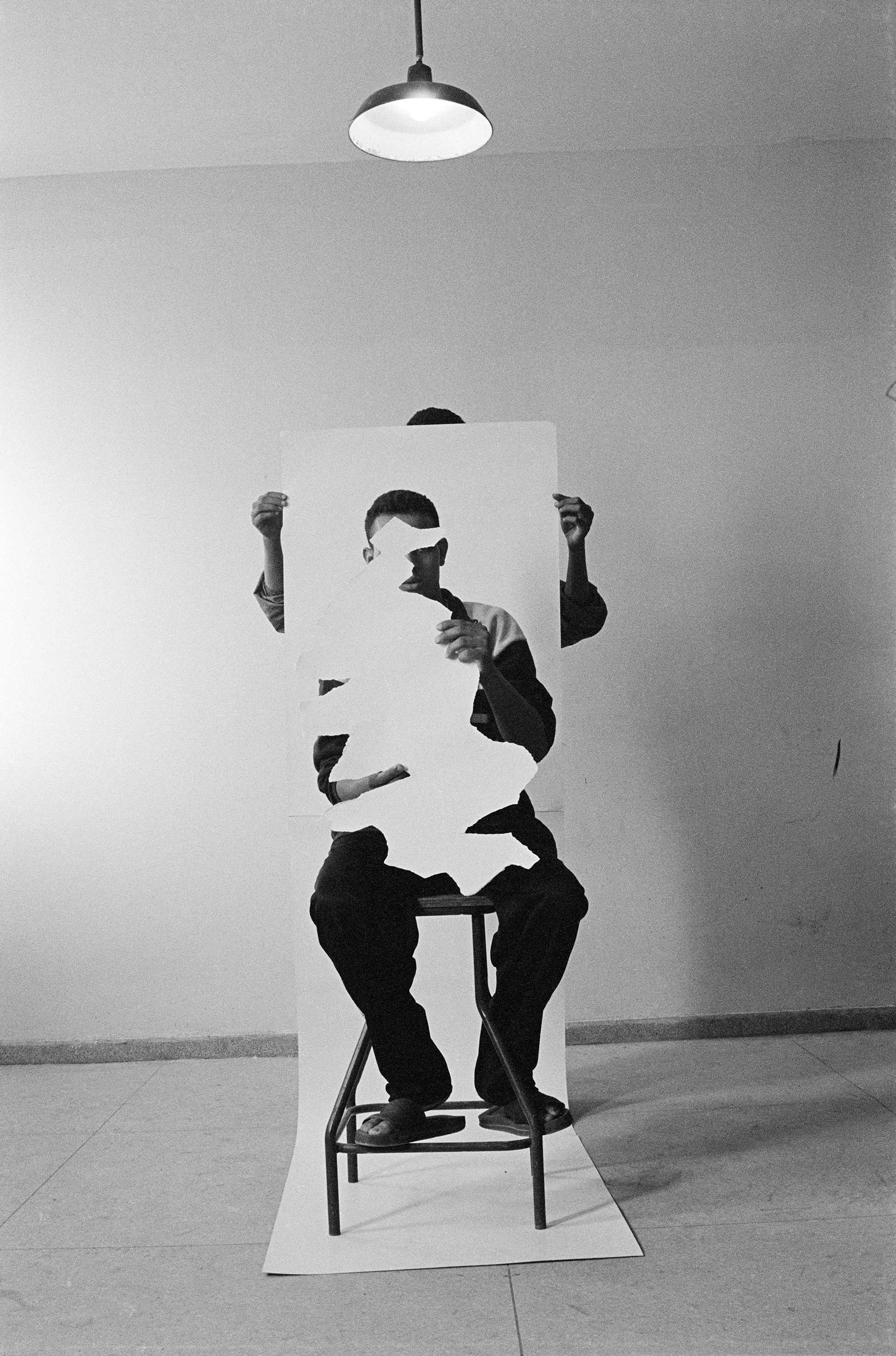

Born in Marrakech in 1968, Benohoud studied visual arts at Ecole Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in France, before returning to Morocco to teach high school art to 11-15 year-olds in 1987. He quickly became bored with the rigidity of the four hour-long art classes he taught, “so I set up a makeshift studio in my classroom to photograph my students whenever I felt the need.” Between 1994 and 2002, he took hundreds of staged black and white photographs for his series, La Salle de Classe (The Classroom), which has now been published in a new book by Loose Joints. In the images, pupils sit working at desks stacked on top of one another; children play in outfits they’ve crafted: legs and arms obscured by cardboard tubes; while the classrooms themselves are decorated in art class materials. The images are a celebration of youth but also serve to criticise the controlled education system at the time, and what he saw as its failures.

Teaching showed Benohoud how trapped his pupils were both socially and economically: “my students come from a disadvantaged social background (a situation that is also found even in the most developed countries in Europe or the United States). But since I am Moroccan, I am of course speaking about my country,” he says. “When parents live in this precariousness, children have no chance of continuing their studies. In most of these families, and for financial reasons, girls are married off very young while they are still in school. And for boys, even if they manage to get their baccalaureate, they do not continue their studies due to lack of means. They most often end up practicing the profession of their father, who is often a farmer or worker.” His classroom became an imagined world in which they could find true freedom.

“We have a very rich history, heritage, and culture. The problem is the traditions that we can’t seem to change. The weight of the past is suffocating us despite this facade of modernity”

The work was socio-political in the same way his series Ânes Situ (Donkey in situ) was a statement about the paradoxes in Casablanca that have resulted from quick development, where contemporary architecture and luxurious cars like Bentleys share the same roads as donkeys. And his work, The Hole, used the image of a pothole as a metaphor for people who are stuck, trying to get themselves out of the way they are living but trapped by their circumstances. In fantastical imagery that is completely real but highly unlikely, he reflects on Moroccan society and the ways in which he thinks that it doesn’t function.

After seven years of living in France, Benohoud returned to Morocco to find a country that had embraced the internet and was globally-minded, but where, for the average person in society, not much had changed. “Despite the modernity that has caught up with us, Moroccans struggle to free themselves,” he says. “We have a very rich history, heritage, and culture. The problem I’m pointing out is the traditions we’ve inherited and that we can’t seem to change. The weight of the past is suffocating us despite this facade of modernity. It’s their right and sometimes even their duty for people to cling to their past. We’re obliged to obediently follow this heritage without questioning it because if we don’t respect it, it can become a crime.”

Since coming to power in 1999, King Mohammed VI has pursued an ambitious modernisation agenda in Morocco with a series of reforms that have improved the economy, schooling and infrastructure of the country. Every rural Moroccan now has access to electricity and drinking water (up from less than half in 2000); while average life expectancy has increased and the absolute poverty rate has declined. But, he told the Guardian: “You see people driving in the wrong direction on the motorway, or not stopping at red lights; others throwing stuff out of windows; donkeys weaving through traffic. There are laws, but everyone just does as they please. It is the world upside-down.”

In The Hole, Benohoud takes photographs of homeowners in Marrakech’s old medina in rooms that look like so many others in Morocco, with low sofas and patterned cushions, kilim rugs, and tiled floors. But his compositions are uncanny. Blending humour and absurdity with the real, he captures two men dangling upside-down as they break through holes in the ceiling’s plaster-work; a woman sitting, unperturbed, in a hole carved in her chequered floor. Body parts, like hands, torsos and feet, punch through walls. “The idea is to show a society swallowed up in a hole and unable to get out,” says Benohoud.

“In everyday life, much like in Western countries, we are suffering from inflation and the gap is widening more and more between the rich and other social classes,” he says. In 2015, he began photographing “people working hard to make ends meet” in his native Marrakech, asking strangers if he could dig holes in their living room floors, walls and ceilings. Then he photographed the homeowners poking out of them. Although the images look photoshopped, in reality: “I arrive with a small team made up of masons, painters, tilers and choose a place in the house, often in the living room, because there is more space and step back to take pictures.”

The work lasts a day or two even if the shots don’t last more than a few seconds, he says. In one picture, ten holes were carved in a small room with orange furniture, a pot of tea stewing on a silver platter on the floor, while more than half a dozen people poke their bodies through. The expressions on their faces are comical, like they might laugh at any point. In another, three walls in a series of narrow rooms are carved, a person sitting in each, that gives the feel of an optical illusion; meanwhile a woman sits in her hole beside a pile of rubble, a bunch of colourful flowers nearby.

Before digging Benohoud will make sure that he can find the same tiles, with the same colours and patterns, in specialist stores so that he can replace what he has destroyed, and instructs the workers to put everything back as if nothing had happened at all.

Sometimes several families live in the same house and each family occupies only one bedroom, while other spaces are often communal. The families he photographs “organise their interiors within their means.” In one picture, three men emerge from the red and black, woven-carpet of a small living room, all of them looking towards the austere yellow walls blankly. In another, six hands clasp each other in sets of three handshakes.

“The individual does not exist in our society because it is all about the community, the tribe, and the family. What can the individual facing the power of these entities do? Either respect the rules, values, and traditions or he is condemned to exclusion or marginalisation.” Feeling trapped is not always about wealth and social status but also by the intensity of community more generally.

Benohoud’s work is a conversation about freedom and control, as well as “this question of power,” he says. By distorting reality and comparing unlikely things, he offers a light-hearted critique of post-colonial identity, showing both the hope and despair he sees in society. “For society to move forward, it is necessary for it to allow its citizens this freedom of expression without any value judgment. It must accept criticism and different, even contradictory, points of view. For the rest, on the economic level for example, we are fighting just like Westerners to improve daily life, whether in terms of the economy, health, or education.”