All images © Arthur ‘Weegee’ Fellig, courtesy of The International Centre of Photography and The Henri Cartier Bresson Foundation

Years before social media, the photographer was already critical of our obsession with celebrity culture and mocked the idea of spectacle through his caricatures

“In post-industrial societies where mass production and media predominate,” begins Guy Debord’s seminal work Society of the Spectacle, “life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly experienced has been replaced with its representation in the form of images.” The book sets the tone for the International Centre of Photography’s new show, in collaboration with the Henri Cartier Bresson Foundation, Weegee: Society of the Spectacle, which opened in January.

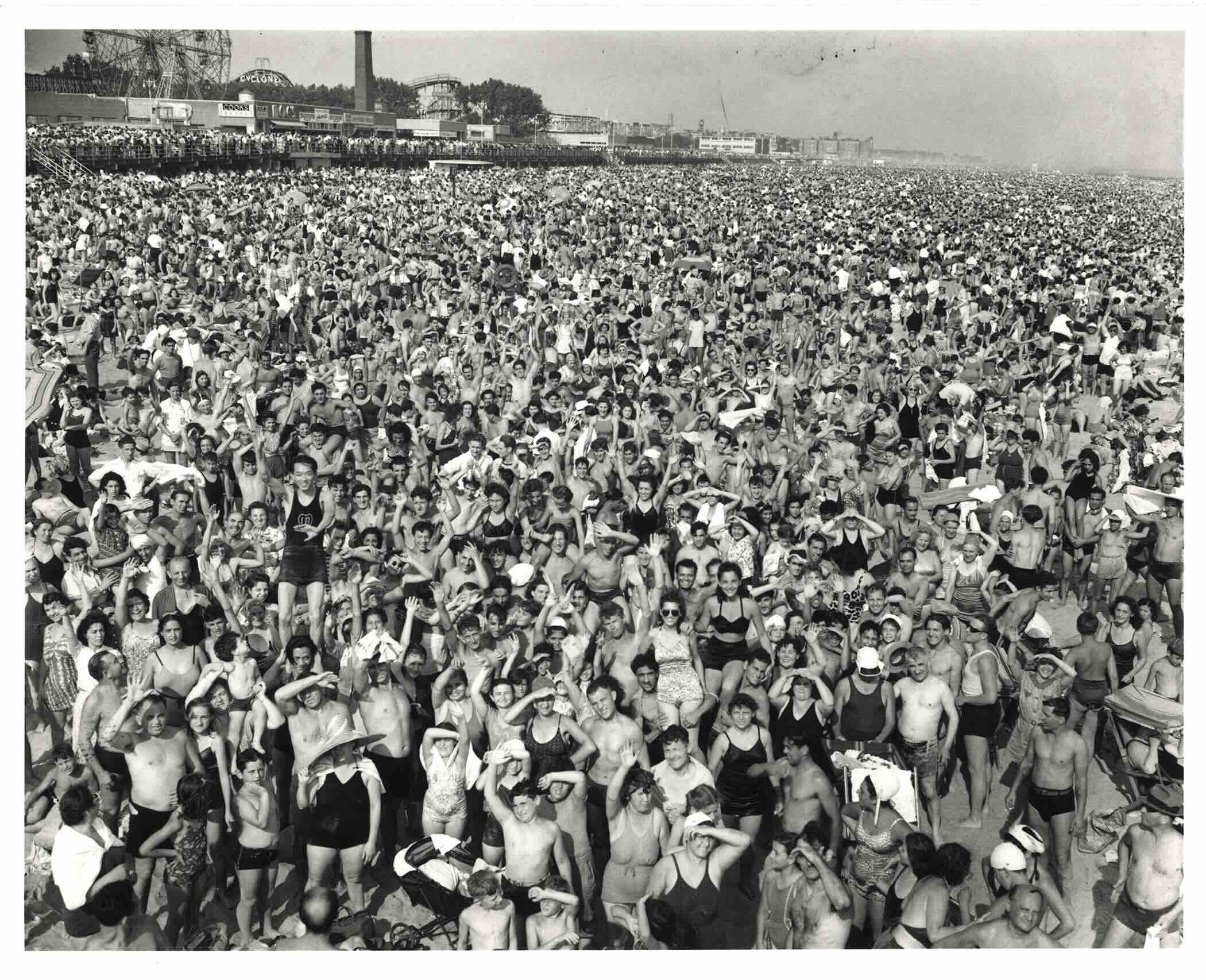

Though Weegee was shooting decades before the invention of mobile phones and social media, he managed to foresee the centrality of images – particularly the shocking kind – in today’s zeitgeist (especially interesting when one considers that Weegee got his nickname from the phonetic pronunciation of the Ouija board, since he managed to arrive at crime scenes before the police).

There couldn’t be a more urgent time to interrogate the idea of spectacle, which has become an overwhelming force in our daily life. Today’s shortened attention spans, addictive reels, and the quick and easy dissemination of violent images, coupled with the ease of AI to change any image into a grotesque caricature of reality, calls Weegee’s work into an altogether new light.

“Weegee wanted to point out the fact that, in America, everything is transformed into a spectacle. Even death”

Born in Ukraine, Arthur ‘Weegee’ Fellig began working in New York City photographing crime scenes, especially car crashes, but was also fascinated by Hollywood and all its illusory glamour. Drawn largely from ICP’s Weegee collection, comprising his entire studio archive and the most comprehensive holdings of the photographer’s work, there is something contradictory at first glance about his starkly real crime-scene images and the hyperidealised celebrity culture of tinsel town. And yet the images are similar in that they present the viewer with something extraordinary, demanding our attention and highlighting the power of an image on not only the individual but the collective. Director of the Henri Cartier Bresson Foundation and show curator Clément Chéroux tells me, “I built this retrospective because I wanted to understand why there was such a difference in the beginning of Weegee’s career and the second part of his career.”

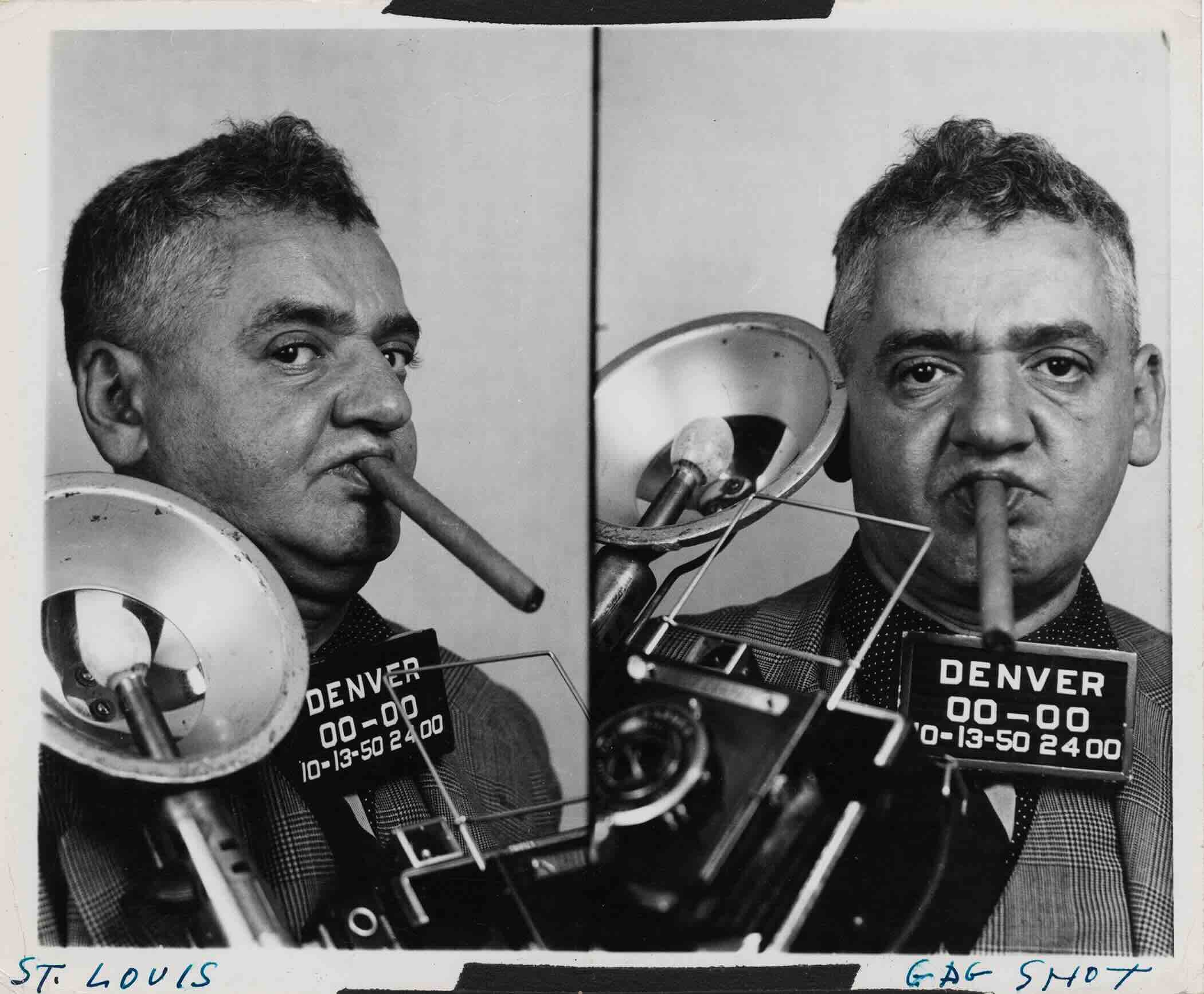

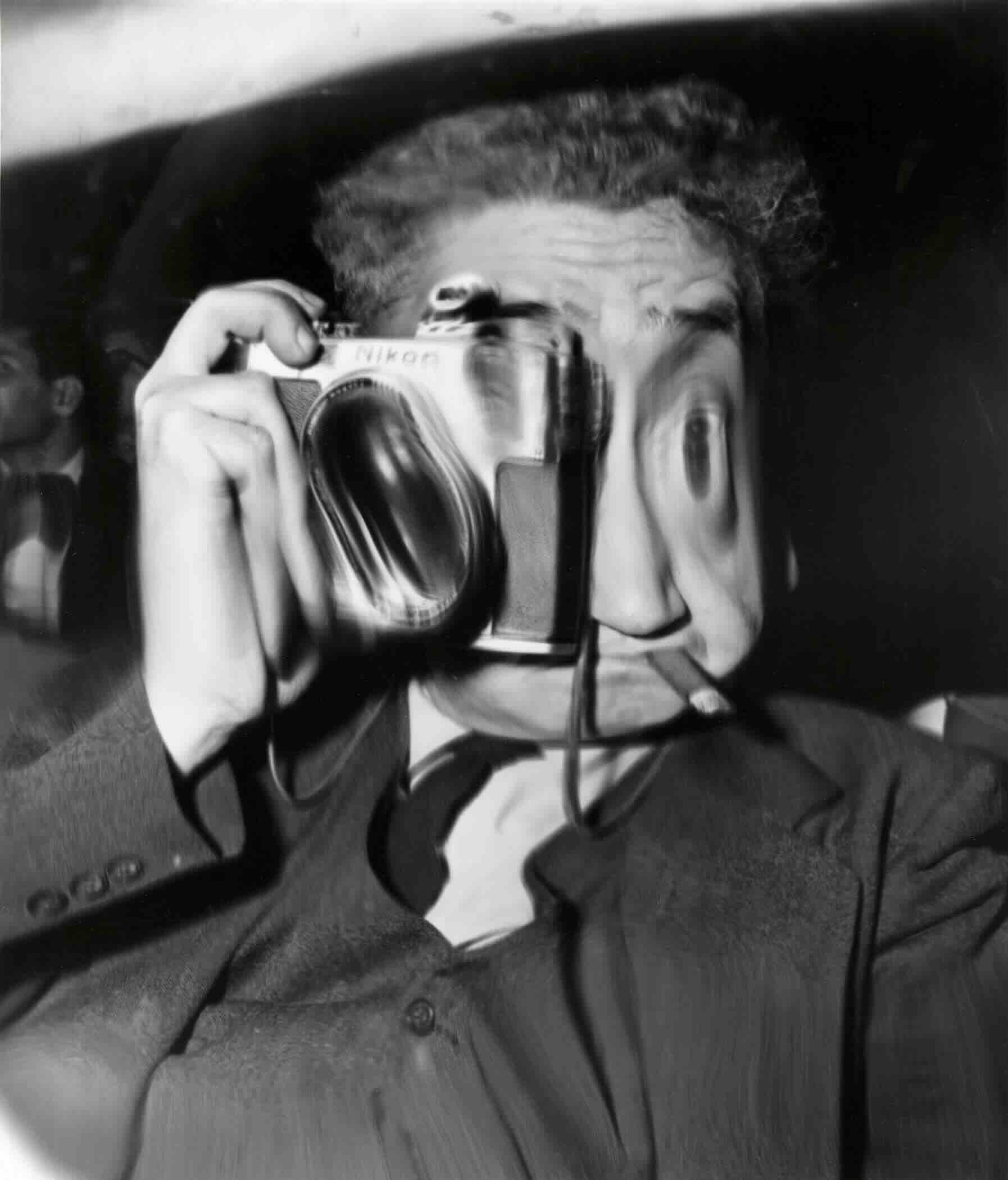

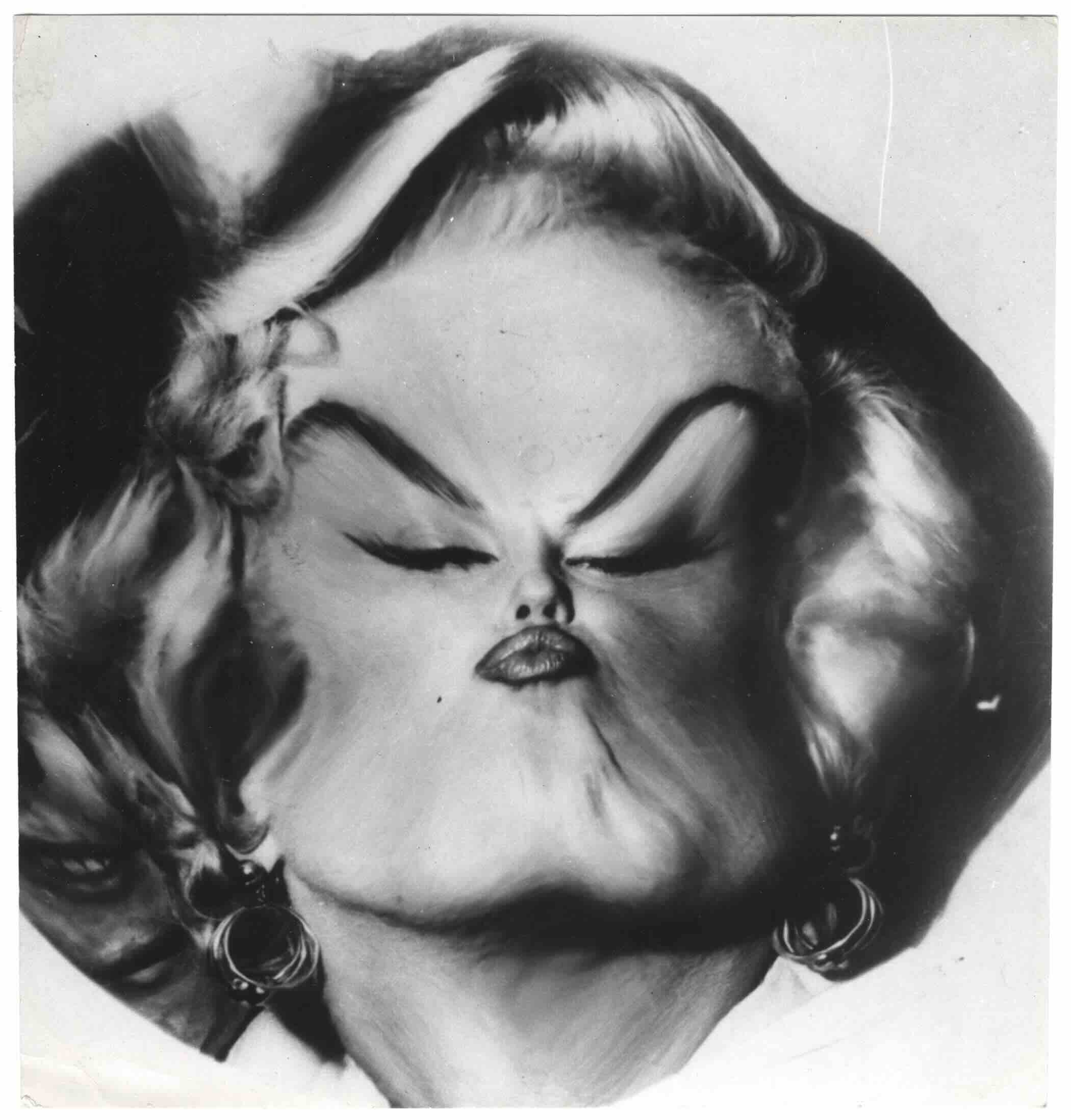

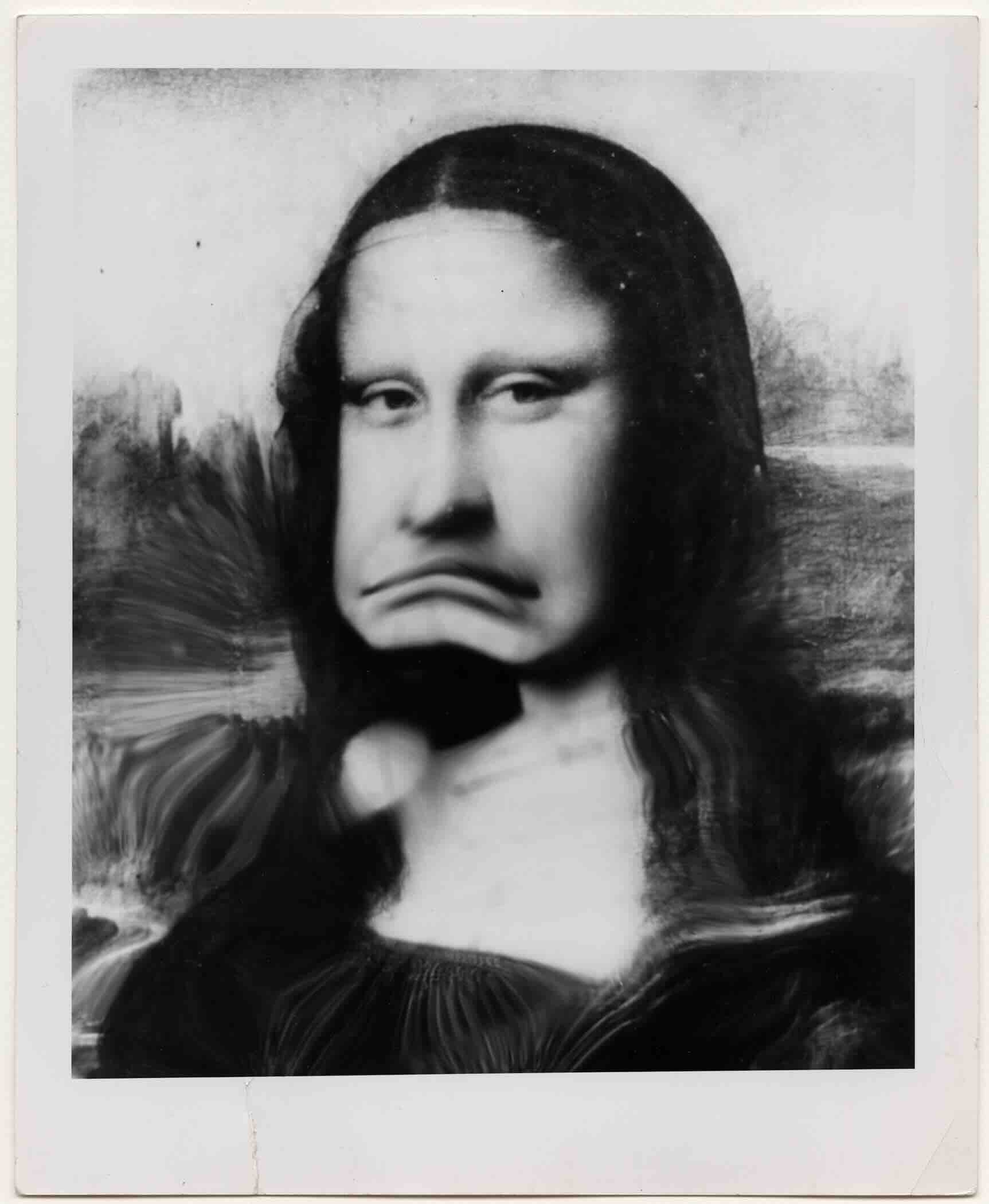

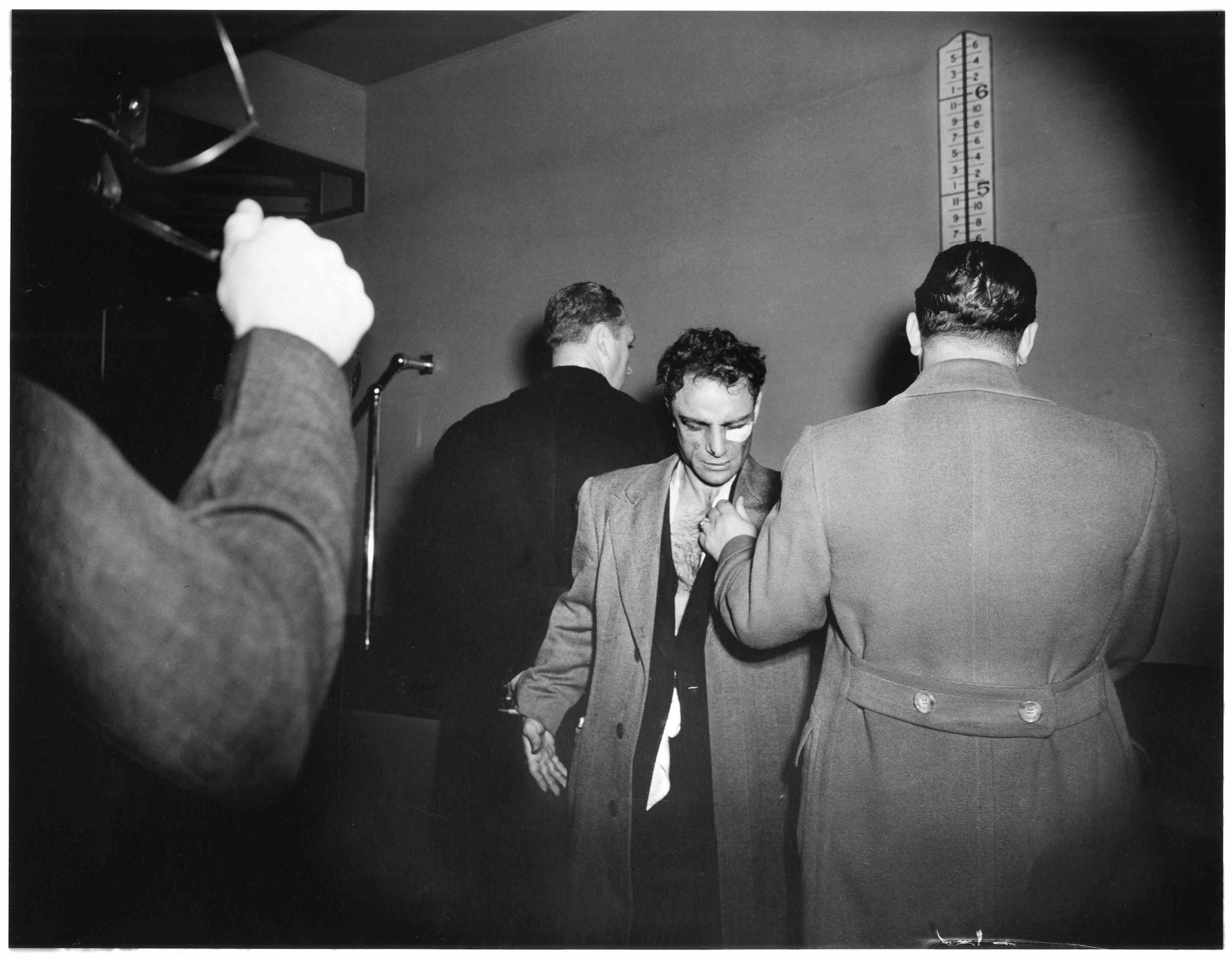

The show is separated into three sections spanning the growth of Weegee’s career: The Spectacle of the News presents crime scenes, car accidents and fires at night, where the onlookers are as much the subject as the events themselves. The Society of Spectators sees the people on the fringes of the main action – from high-society parties to street scenes. Hollywood Distortions focuses on the later Weegee years and his experimentation techniques that satirised Hollywood stars and celebrity fanaticism through exaggerated photo-caricatures which resemble Instagram’s funny filters of today’s technology.

“Of course, I am a big fan of the photographs that he took for newspapers,” Chéroux tells me. “But then a few years ago I discovered that there was another Weegee that went to Hollywood in 1948 and who started making what he was calling photo-caricature.” Taking a photograph of a celebrity such as Marilyn Monroe or politicians like Ronald Reagan, Weegee would distort it using a piece of glass or plastic in the darkroom and distort the image, then publishing them in the newspaper.

“So I was completely puzzled by the fact that the same photographer could have started as a straight photographer taking photographs in New York during the night with a flash in a documentary approach and a few years later become someone who is manipulating the photograph in the dark room. It’s quite unusual in the history of photography in the 20th century,” expands the show’s curator. The exhibition is also accompanied by a new publication created by the Foundation and Thames & Hudson that explores the impact of Weegee’s art and his critical view of urban spectacle.

Weegee was from a Jewish family who immigrated to the US and had a strong social consciousness – he was interested in documenting social issues, Chéroux thinks, and depicting the life of the working class. Weegee worked for Leftist newspaper PM Daily that didn’t have advertising in order to remain independent, “which is very rare in the US in the 30s,” explains Chéroux.

“He was not an activist himself, but he really had a strong political consciousness. And I think that he was interested in his photographs showing how the tabloid press was transforming crimes, fires, car crashes – which are really tragedies – into spectacles.” Chéroux is interested in showing that through this political consciousness, “Weegee wanted to say something about America, he wanted to point out the fact that, in America, everything is transformed into a spectacle. Even death.”

Interestingly, though Debord and Weegee never met and Weegee was working far before Debord, the philosopher used the title of Weegee’s book Naked City in one of his collages. Chéroux started with that link, asking, “is there a connection between the two? It’s a kind of intellectual construction. There is no [actual] link between the two. Weegee died a year after the book was published.” But as a curator, “as a photo historian” Chéroux says he uses “Debord to explain that Weegee already had this intuition 30 or 20 years before the book was published.”

Sometimes, Chéroux thinks the clippings are more interesting than the prints themselves because of the layout of the magazines, the titles, the design and the method of communication. “It’s a cultural object that says a lot about this culture of celebrity.”

If he was working today, Weegee might have either been alarmed at or revelled in the fact of how grossly exaggerated the spectacle has become on our screens. What were ‘violent’ images seem to be innocent by today’s standards. This latest retrospective begs the question; where lies the border of desensitisation?