All images © Rosa Franjic, unless stated otherwise

Italian-Bosnian Rosa Franjic and her partner travelled to the Yemeni island to meet friends working on preserving its staggering biodiversity

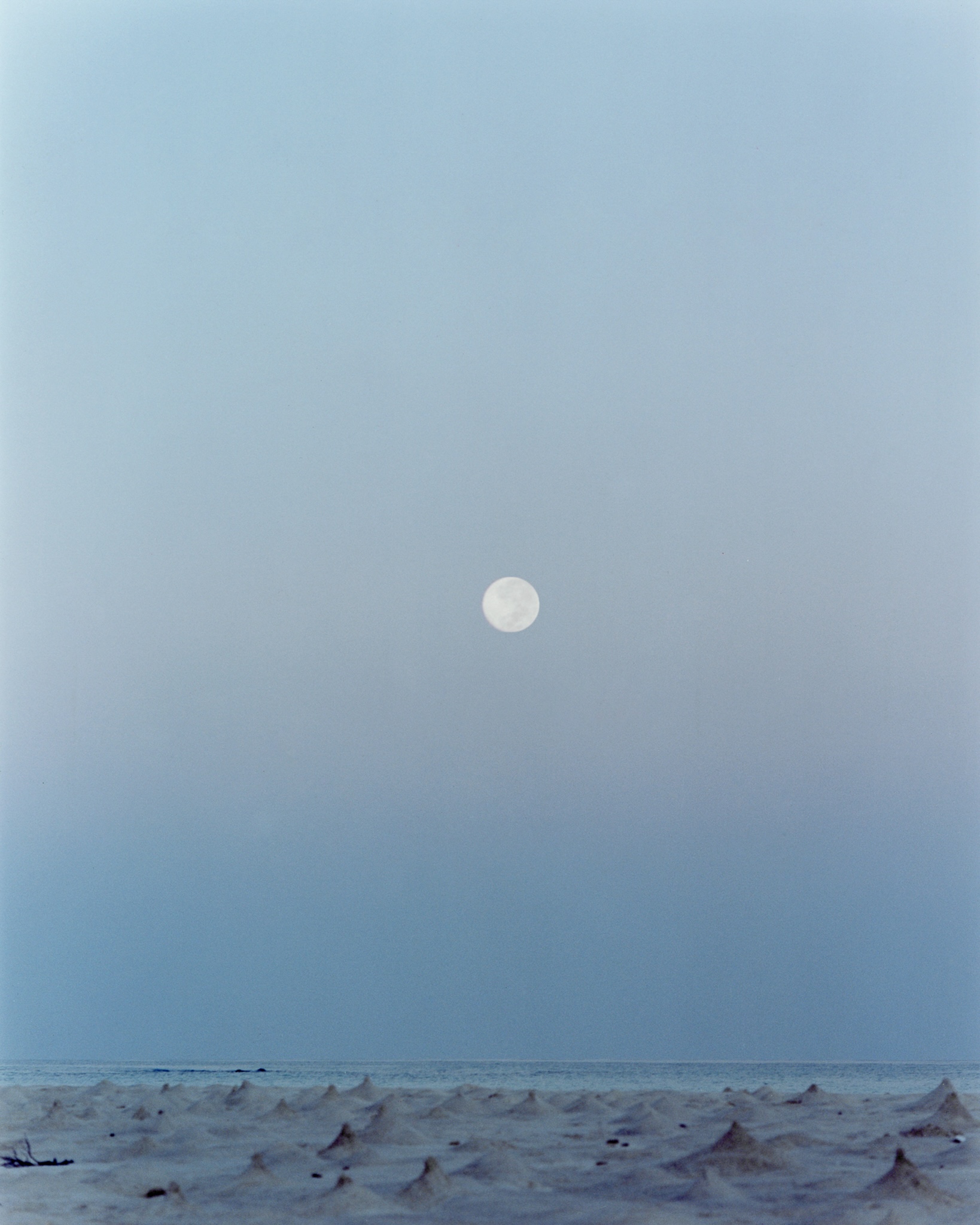

Photographer Rosa Franjic first set foot on Socotra by way of her partner, Tarim Contin-Kennedy, who has deep ties to Yemen. Its famous island, Socotra, has become a tourist hot-spot in recent years, but Franjic set out to focus on its centuries-old traditions through quiet and meditative images, and found resilience woven into daily life. On the island, modernity looms as both a promise and a threat.

Speaking with BJP, Franjic reflects on the motivations behind her work, the friendships that shaped her perspective, and the delicate balance between storytelling and intrusion. She introduces us to the individuals who became central to her project – the guardians of Socotra’s fragile ecosystem, the stewards of its vanishing agricultural practices, and the defiance of those who resist the tide of problematic change.

But photographing Socotra came with its challenges. Franjic speaks candidly about the limitations she faced, particularly when it came to documenting the lives of women, and how putting down her camera often led to deeper, more meaningful interactions. Now, as she looks to new projects – particularly a return to her Bosnian roots – she continues to explore photography as a means of preserving the overlooked and reimagining narratives that exist beyond the mainstream gaze.

“When I put my camera down, it permitted me to engage with my Socotri woman friends in a much more authentic manner that served the dual purpose of significantly reducing mine, and most other foreigners on Socotra’s, inescapable Western gaze”

Dalia Al-Dujaili: What was your motivation for the project and what is your relationship to Socotra generally?

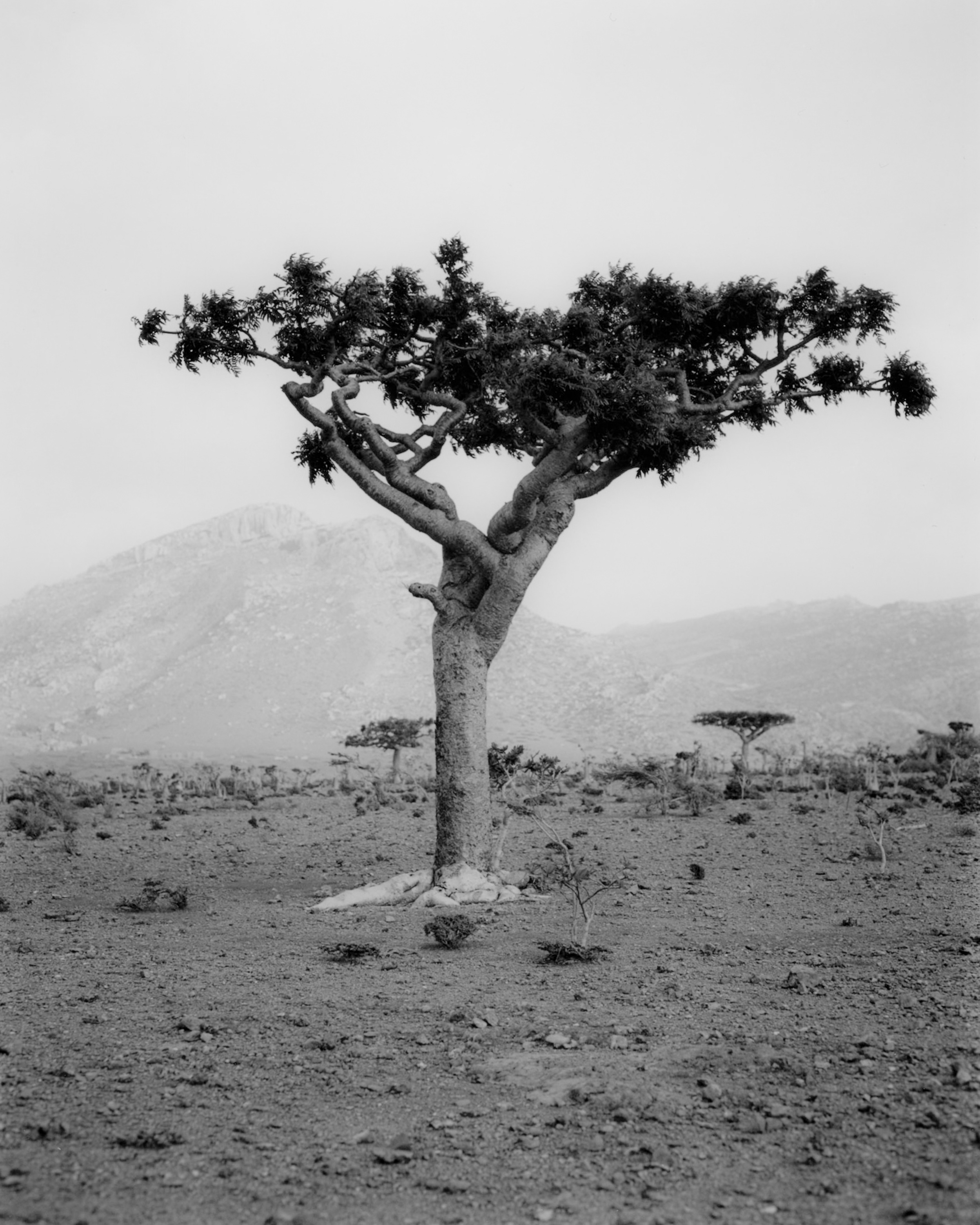

Rosa Franjic: I came across Socotra through my partner Tarim who spent the majority of his life in Yemen and, due to his background in zoology and conservation of biodiversity, formed a special bond with Socotra and its rich endemic biodiversity. Prior to going, I had only heard about Yemen through its dismal media representation and the much more sanguine stories my partner recounted. It was only after having spent some time there that I became aware of the island’s age-old history, rich cultural and natural heritage, and the compelling, unique stories of the island’s inhabitants, who for thousands of years have been the stewards of this rich heritage.

DA: Tell me about some of the people in the images and how you met them.

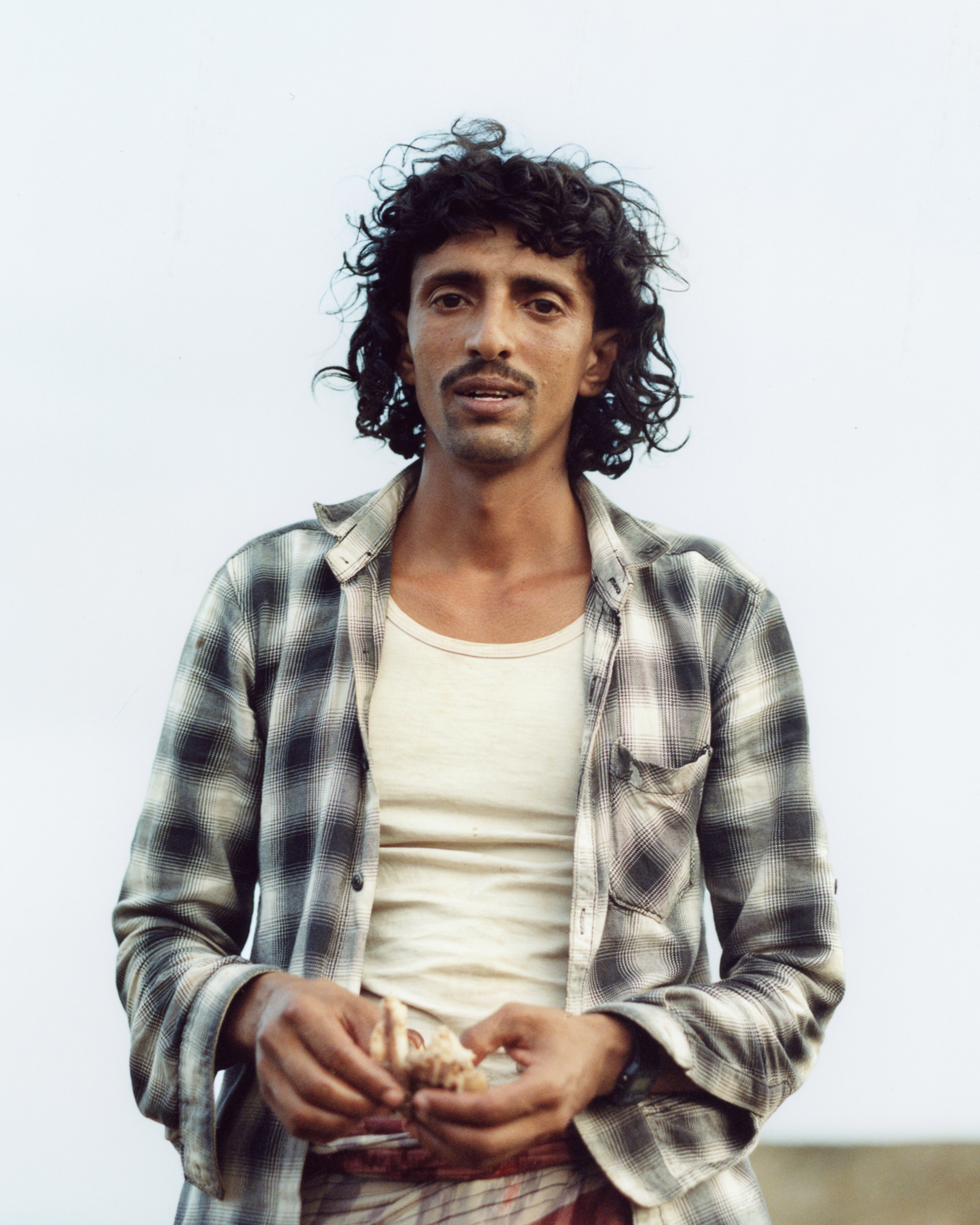

RF: This project was born from the desire to capture a contemporary snapshot from within a reality marked by rapid development and chaotic, often destructive, change. I hoped that my photos could give a face to the people that represent the antithesis of this change, those who, by way of their daily lives, uphold millennial traditional conservation measures and who we are incidentally lucky enough to call friends. Examples of these friends include the De Myuri brothers of the Firmhin plateau, the largest (and only) forest of endemic Dragon blood trees, and the custodians of one of only two Dragonblood tree nurseries on earth.

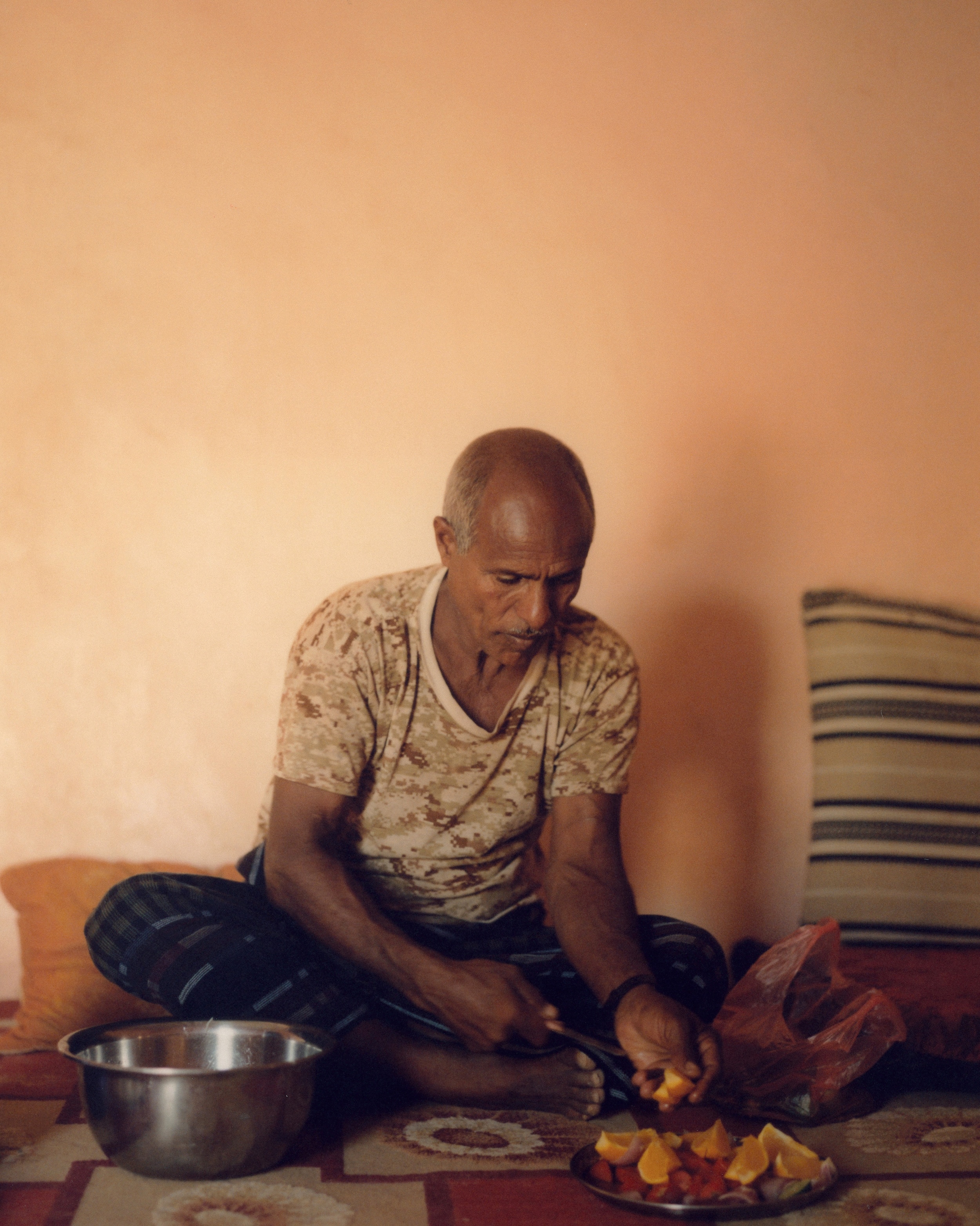

Another of these friends is Mona in her organic garden where she is one of few to uphold rapidly disappearing traditional agricultural practices. Lastly there is ammi (Uncle) Mohammed and his family, my partner’s longtime best friends on Socotra, who by way of their humble yet meaningful day-to-day lives in the quaint seaside village of Hayf represent a poignant, deliberate countermeasure to the detriments of modern globalised life.

DA: What stood out to you about Socotra and Yemen more widely? And how did this reflect in the images you took?

RF: Aside from its breathtaking nature, what stood out to me most about Socotra was its inhabitants’ insurmountable dedication to preserving their natural and cultural heritage, often by means of age-old traditions still very much alive today. Furthermore I was struck by their immense hospitality and willingness to allow me into their daily lives and intimate spaces. In my photos I strive to portray the dichotomy between the subtle beauty of rural life versus the lively chaos of its capital, Hadiboh.

DA: What were the challenges, and what were the lessons you learned whilst shooting in Socotra?

RF: Whilst on Socotra I very much hoped to be able to capture the many compelling stories of Socotri women I came across while there. Unfortunately, my hopes were met with a widespread opposition to women being photographed as per local custom, and so I was only able to capture the story of Mona and her traditional organic agricultural practices. Contrary to my expectations, I ended up finding that when I put my camera down, it permitted me to engage with my Socotri woman friends in a much more authentic manner that served the dual purpose of significantly reducing mine, and most other foreigners on Socotra’s, inescapable Western gaze.

DA: How do you wish to evolve as a photographer and are you working on anything new at the moment?

RF: I hope to use photography as a means to explore our world’s infinite diversity of ways of living. My career in the fashion sector so far has allowed me to meet many talented artists that continue to inspire me. But within their art, it is not the fashion that speaks to me most. More-so, I find great inspiration in photographic themes that convey the nexus between connection, knowledge, memory and modernity. I love how, through the still photograph, people, phenomena and landscapes open up to me and allow me in as a temporary member of their ephemeral existence.

Building on previous projects, I hope to use the near-future to focus on my Bosnian roots. More specifically, and in a similar manner to what I sought to accomplish in Yemen, I hope to connect with a land I left more than 25 years ago, and tell the stories of generational resilience, proximity to nature and hope often excluded from conventional media representation of Bosnia.