© Imran Perretta, courtesy of Somerset House

The artist uses a BlackBerry phone to delve back in time to the 2011 London riots, unravelling an intersection of class, race, and violence in his new Somerset House show

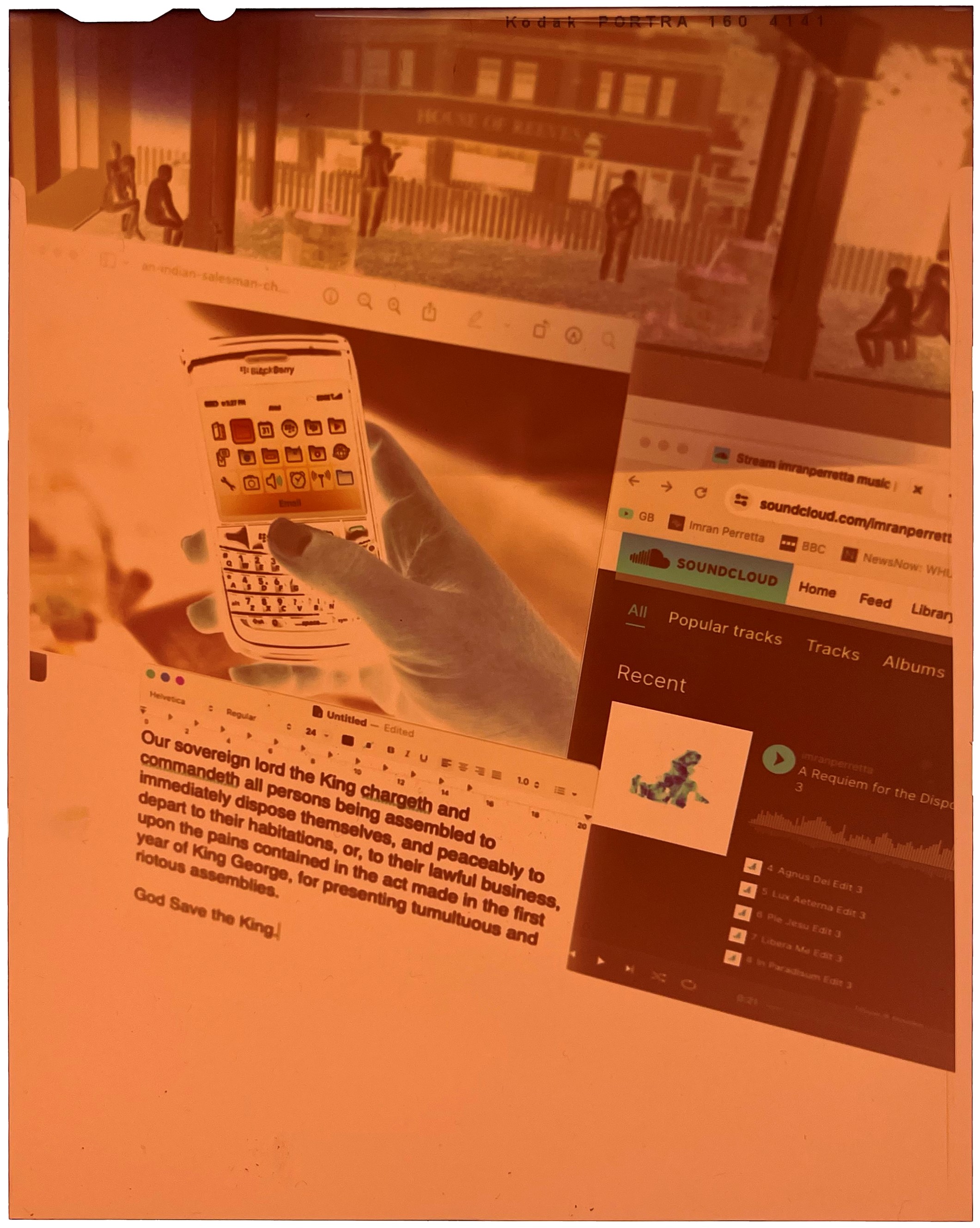

A BlackBerry Bold 9650 mobile phone, first released back in 2010, is entombed in a transparent glass vitrine atop a museum plinth. On its rectangular landscape screen, like a pocket-sized cinema, a 2011 video plays grainy footage shot from a similar handheld device. Burning red flames furiously engulf buildings, black smoke billowing into the night sky. The shaky film clip depicts the House of Reeves, a furniture store in Croydon, on fire during the 2011 England riots. The moving image loops, as though caught in time, haunting the present. The object is part of Imran Perretta’s exhibition A Riot in Three Acts at Somerset House.

Clearing out his father’s house a couple of years ago, Perretta came across his own BlackBerry from 2011, which contained a copy of the same digital file. “It was striking revisiting those images”, explains the artist, “realising that the material, socio-economic, political, and ideological conditions that led to that unrest happening in 2011, none of it had changed. If anything it’s significantly worse, it’s been over a decade of austerity now”. A Riot in Three Acts represents Perretta’s quest to think through the legacies of that summer, what he “felt was the righteous anger of the people who revolted”, and the considerably complex emotional dimension of what it means to raze a longstanding family-run shop to the ground. While believing in the principle of destroying private property for the common good, Perretta found the arson metabolised the uprising’s insurgency into something else entirely.

“The safety net has failed, social provisions have been disembowelled, everyone apart from the upper crust of the ruling class has struggled these last 13 years”

Exhibited in the neoclassical palace’s opulent Lancaster Rooms is sculptural installation Reeves Corner (2014) and musical composition A Requiem for the Dispossessed (2024). The former is designed like a film studio stage set: a huge oil painting erected on wooden scaffolding portrays a remaining House of Reeves building, suitcases and sale signs visible through the Victorian shop’s ground-floor windows. In front is a recreation of the site where the former store once stood: an attempted garden on derelict wasteland, bound by a white picket fence. Strewn amongst gravel is discarded rubbish – Lucozade or water bottles, cigarette packets, hairspray cans, plastic bags, cardboard boxes. Large concrete planting tubs cherish a collection of bare branches and dying weeds, some of which have escaped their enclosure.

Playing through the space is Perretta’s sound piece performed by Manchester Camerata, a cinematic score in the style of a classical requiem, intended to be a sonic representation of the uprising and its aftermath. In a vitrine is a copy of The Mirror newspaper from 09 August 2011, proclaiming ‘YOB RULE’ over an image of Croydon on fire. In the cabinet is also a collage of documentation for the project on negative photographic film, including a screenshot of King George I’s 1714 Riot Act written on an MacBook notes app.

The events of 2011 caused a crisis for liberal and conservative commentators, with politicians and journalists narrating the violence as apolitical and its participants inherently criminal, both supposedly existing outside of any social context. Other explanations were outright racist: historian David Starkey, for example, told BBC Newsnight that “the whites have become Black”. The unrest had actually been sparked by the murder of unarmed Black man Mark Duggan by the Metropolitan Police, which Perretta acknowledges alongside deeper structures of feeling at the time. With “what felt like the fall of capitalism in 2008 and then the consequent government austerity”, he explains, “it was a very febrile atmosphere”.

A month later, ‘Occupy’ protests would spread across the world, followed by more than a decade of surging left-wing and right-wing movements. Perretta distinguishes the 2011 and 2024 riots in their politics and targets, but explains “the safety net has failed, social provisions have been disembowelled, everyone apart from the upper crust of the ruling class has struggled these last 13 years. As much as the people involved in those extremist riots would quite literally want to kill someone like me”, he reflects on this summer, “I understand entirely that the material condition that they find themselves in is untenable, because it is the very same condition that many diverse communities in the UK are mired in.”

Riots or rebellions have been a frequent occurrence in Britain for centuries – mere metres from Somerset House is a site that formerly housed Savoy Palace, destroyed during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. Whether motivated by white supremacy as in 1919, or against police racism as in 1981, collective violence often erupts when resource distribution mediated through social hierarchies is contested. Of the 2024 summer’s episode, Perretta tells me that he would “rather they punch up at the ruling class than violently scape-goat communities of colour, but, after 13 years of austerity, the fact of their punching is inevitable.”

Given the exhibition’s analysis of power, its location only adds to the impact: a neoclassical complex in central London, rebuilt in 1776-1801 to house the Royal Navy and the Admiralty, as well as the Stamp Office and Tax Office. A nineteenth-century extension, the New Wing with its grandiose Lancaster Rooms was occupied by the Inland Revenue, later HMRC, until 2011 – coincidentally the year of the unrest. Somerset House was an institution from which the British Empire was ruled, and where the UK state managed the process of extracting wealth from its subjects. Perretta acknowledges it is a complex venue from which to critique the ruling class, but sees an important project in using art to reckon with Somerset House’s past and “remaking in real time of what this building means and who it’s for.” Re-creating a South London wasteland at such a site can feel somewhat surrealist.

Encasing the BlackBerry in a vitrine is kind of wryly absurd, while also reflecting on the ways in which museums impose frameworks on their artefacts, drawing on an intellectual apparatus historically shaped by imperial attempts to collect and categorise the world. The project prompted the artist to consider the politics of property: how it is distributed, governed, and accessed. Austerity was first invented at the end of World War I to protect capitalism from crisis, with the public calling for alternative systems, restricting the imaginative and material space for dissent by shifting wealth to an elite minority. After its reintroduction in 2010 by the Liberal-Conservative Coalition, Tory government ministers spent subsequent years curtailing the public’s right to peacefully protest, while hardening borders under the pretence of resource scarcity.

Perretta understands the irony of symbolically relocating a privately-owned and publicly-inaccessible area of unused scrubland to a privately-owned but publicly-accessible palace, both deeply contested grounds. For him, exhibiting the work at Somerset House offered an opportunity to stage a version of Reeves Corner where the public can congregate to memorialise the events of 2011, meditate on their legacy, and build forms of solidarity in ways impossible amongst the fenced-off ruins in Croydon. With Labour effectively promising more austerity and anti-migrant rhetoric in 2024, A Riot in Three Acts insists that the insurgent energy of 2011 will only erupt again.