All work images © Joy Gregory. Courtesy Art on the Underground

In a time of deep toxicity around immigration, the south London artist uses cameraless photography to foster care and conversations

Of all the works Joy Gregory has made in her 40-year career, the one that most excited the children in her extended family was A Little Slice of Paradise, a collage which fronted London Underground’s 39th pocket map and advertising boards. Seeing her name all over the city was special to them, she says, gesturing to a poster of the image hanging in her Camberwell studio. The collage is a cyanotype of chickweed grown in Tube station gardens, to which Gregory digitally added images of flowers such as daisies, camellias, nasturtiums and dahlias, in homage to the staff-maintained gardens and her long-standing interest in botany.

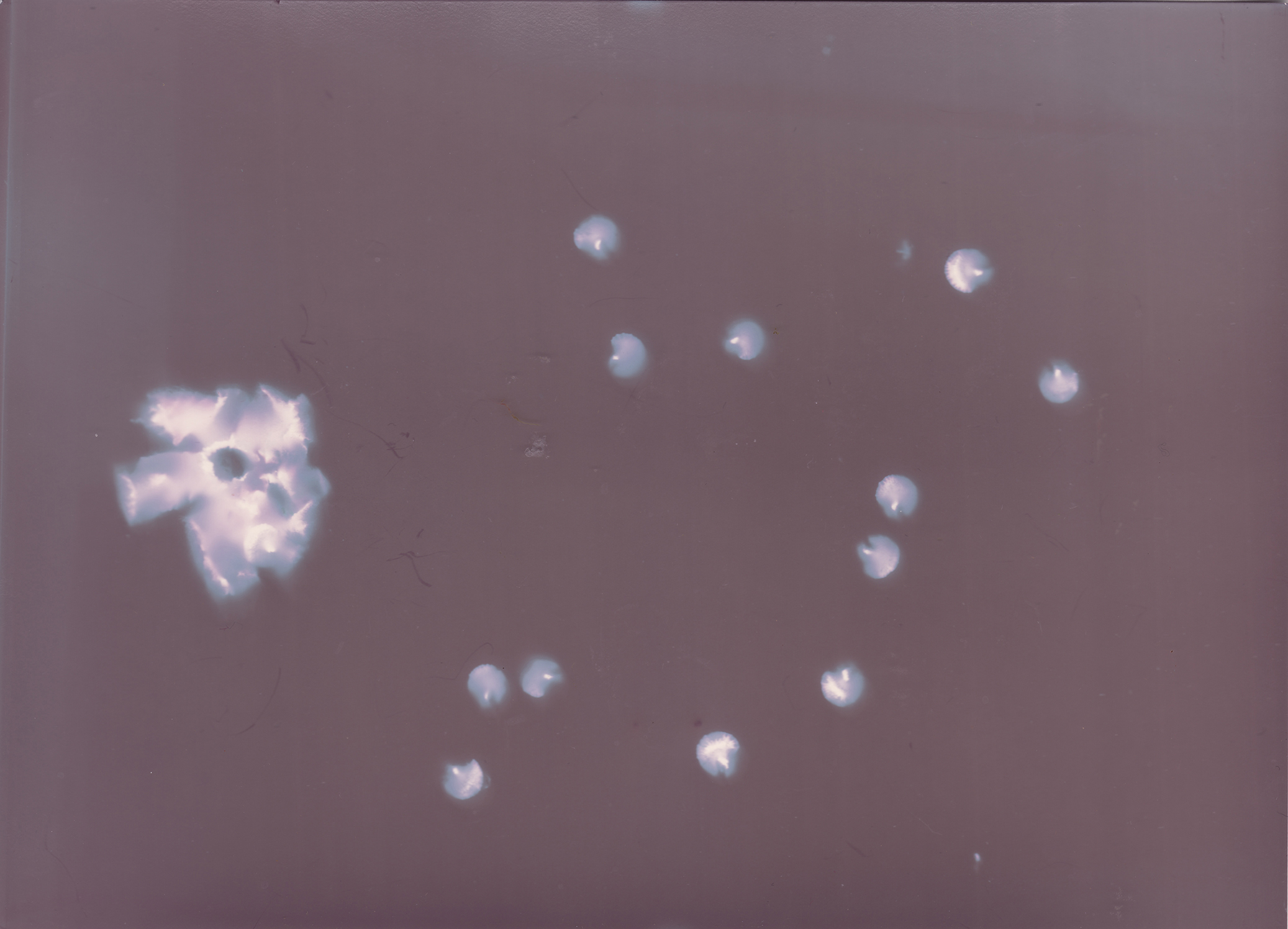

A Little Slice of Paradise was commissioned by Transport for London’s Art on the Underground initiative, which has been responding to and furnishing London’s transport network since 2000. (Artists have always been involved in the Tube’s permanent infrastructure however, from Eric Aumonier’s 1940 sculpture atop East Finchley station to Eduardo Paolozzi’s mosaics at Tottenham Court Road). Now Gregory has been commissioned again by Art on the Underground, this time to create work for Heathrow’s Terminal 4 station. The 64-year- old will present cyanotype, monoprint, lumen and nivea print-based works made in collaboration with asylum seekers housed in Hillingdon, in a project titled A Taste of Home. Gregory will also add text to the images, incorporating poems including Seeds in Flight by Khaled Abdallah and Warsan Shire’s Home, as well as culinary references, continuing her focus on migratory and cultural signifiers.

“The language and methods that are used to talk about people who have come from elsewhere is to attack and dehumanise them. But when you hear the stories first-hand, it’s heartbreaking, how people end up in these places”

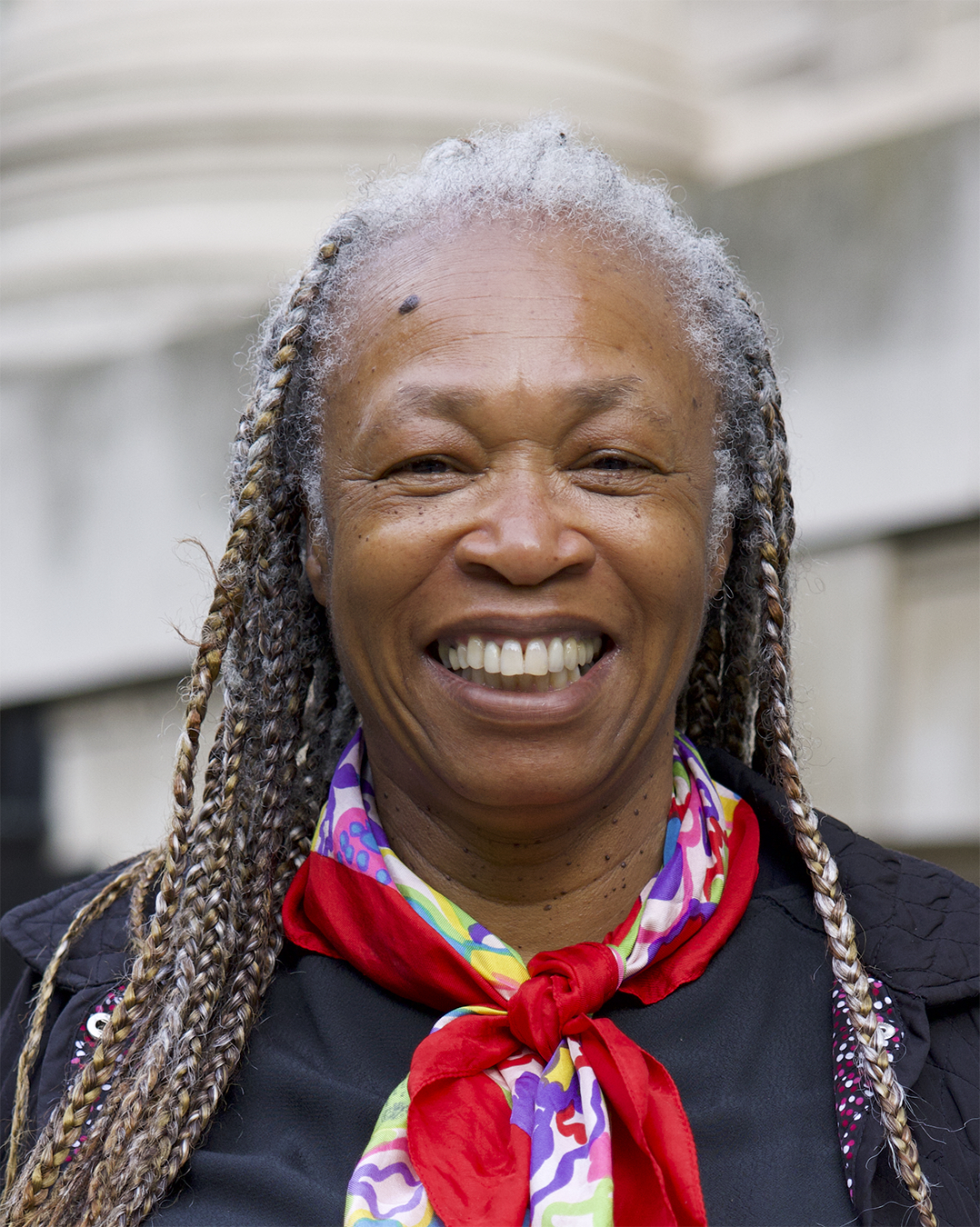

Gregory has long understood the importance of presenting art publicly. She points to her undergraduate studies in the department of communication art and design at Manchester Polytechnic, where she learned the fundamentals of advertising. “I could have left and become an advertising or editorial photographer; it’s a language I understand and enjoy,” she says. Instead she headed to the Royal College of Art, after which she was at the centre of an unsung group of Black British women photographers in the 1980s and 90s. (Gregory recently edited Shining Lights, a loose anthology of the period, including many artists who were ignored for decades). She is also the recipient of the 2023 Freelands Award, and will mount a major solo exhibition and new commission at Whitechapel Gallery in autumn 2025.

“Making something for the public suits my style,” Gregory says, “the idea that people don’t have to go into a particular space to enjoy art.” Love of a Long Vocation, her albumen print portraits of hospital workers, are currently installed at London’s St Mary’s Hospital. Each nurse, doctor and technician received a print; giving people something physical is important, Gregory says. In a political climate in which migrants are routinely demonised, she hopes the Heathrow commission can also have a social impact. “We have to find a way to shift people’s perception but in a very gentle, non-threatening way,” she says. “The language and methods that are used to talk about people who have come from elsewhere is to attack and dehumanise them. But when you hear the stories first-hand, it’s heartbreaking, how people end up in these places.”

Gregory decided to use cameraless images because of the duality of travel: some people cross borders for pleasure, others because they have no choice. Maintaining a connection with the site – Heathrow is the world’s second busiest terminal for international passengers – was essential, as was investigating how forced transit alters ideas of home. “For asylum seekers, the idea of home is not about where you live,” Gregory says, “it’s about where you feel most comfortable.” She connects the work’s social responsibility with her time teaching photography at HMP Holloway in the mid-1990s, a women’s prison with a dedicated education team.

With the help of Art on the Underground curator Sasha Morse and REAP – Refugees in Effective and Active Partnership, Gregory organised lumen printing workshops in an asylum hotel. The process is similar to making cyanotypes but with older photographic paper, creating darker rather than blue backgrounds. “People were really suspicious the first time,” Gregory recalls. “Someone said, ‘So you think this is what refugees need?’ But he was an artist who wanted to know how to get his work shown.” Gregory spoke with the man and suggested a competition to enter, but his residency status meant he was ineligible. The children of claimants – who attend the local school, while their parents are barred from working – gathered around a table scattered with drawing materials. “It’s about creating an environment where everybody feels safe,” Gregory says. “When you don’t know what your future is going to be, doing something new or with your hands can open up conversations.”

Gregory wanted to understand the journeys participants had undertaken, and asked them about favourite foods and plants, often via translators. Words including ‘paprika’ and ‘saffron’ will appear in the Heathrow artworks, while five recipes will feature in an accompanying TfL leaflet. “One of the things that struck me most was the rows of microwave meals in the hotel,” Gregory says. “And what eating them would do to your health waiting five years for your claim. But cooking is so important – breaking bread and friendship.” She mentions her own upbringing in Aylesbury and her fascination when her parents would return from Jamaica or London with mangoes. Having lived in London since 1984, Gregory associates place with cuisine, from Peckham’s Nigerian roots to Brick Lane’s curry houses.

Gregory is following in the footsteps of Rhea Storr, whose 2022 commission Uncommon Observations: The Ground that Moves Us turned Terminal 4’s advertising panels into a narrative of captioned film strips probing how images of Black people are circulated. In terms of materials, Linder’s 2018 photomontage – which referenced the design of Southwark station, said to be inspired by English landscape gardens – is Gregory’s main Art on the Underground forerunner. If her work here has a guiding principle, it is that of the fragment. “When you think about these people’s lives and situations, we only ever encounter fragments,” she says. “The time was short, and I’m only asking specific questions around food, home, flowers.”

Joy Gregory’s Art on the Underground commission, A Taste of Home, is at Heathrow Terminal 4’s London Underground station until 2026