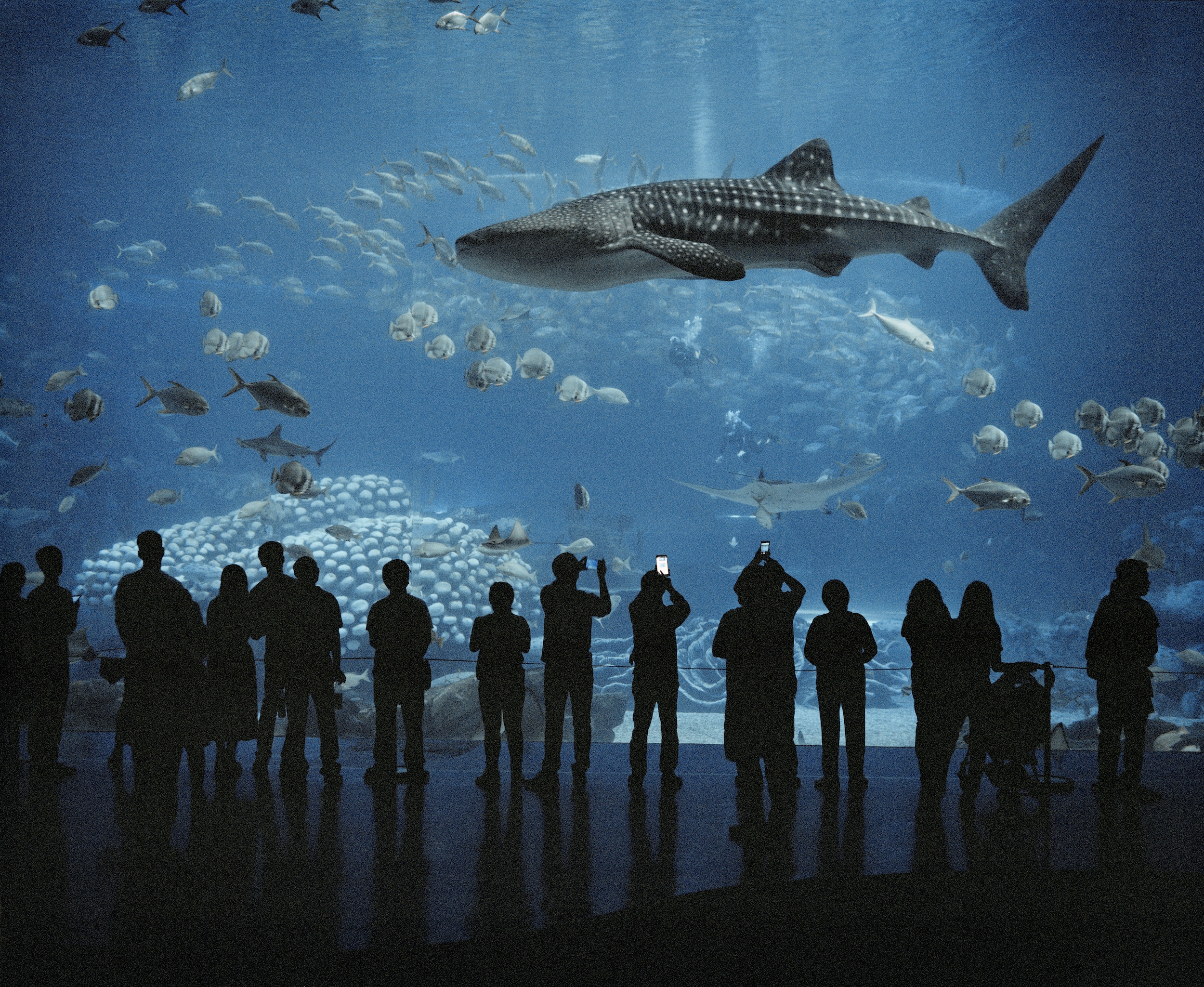

Shanghai Wild Animal Park, Shanghai, China. All images © Zed Nelson

Shot over six years across four continents, ‘The Anthropocene Illusion’ is a disturbing insight into a world in which the natural world is replaced by spectacle

Sat together in front of a computer screen in his home and studio in a leafy north-east London street, Zed Nelson and I are going through the dummy layout of a recently completed project he plans to turn into a book. Shot across four continents, and taking six years to complete, the work addresses our complex relationship with the natural world.

It begins with a stark reminder of an unfolding catastrophe, now in frightening acceleration. “In just a few decades, we humans have altered our world beyond anything it has experienced in tens of millions of years,” he writes in the intro. “Future geologists will find huge concentrations of plastics, the fallout from the burning of fossil fuels and vast deposits of cement used to build our cities. The number of wild animals on Earth has halved in the past 40 years. We are causing creatures and plants to become extinct by removing their habitats.”

“Just as we divorce ourselves from the natural world and destroy it, we do something extraordinary – we create staged-managed versions of the very thing that we’re losing. It offers us reassurance, a collective self-delusion, a mask to what we’re really doing”

The sequence of 70 or so images in the dummy provides some evidence of this, such as a sadly poignant picture of one of only two surviving northern white rhinos – both female – together with one of the rangers responsible for protecting it at Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya. But this is not just another photography project about our destruction of the planet, the language of which, Nelson recognises, has “become somewhat clichéd or overly familiar”. He alludes to the kind of photographs we have all seen countless times before – polar bears surviving on a shrinking piece of ice; burning smokestacks in China – and says while it is still important to document such things, “I wanted to approach the issue from a different visual and psychological angle.

“I have always appreciated the capacity of photography to become a historical artefact. But that’s not why I’m doing this,” he continues. “I am less interested in preserving some image of what is lost than considering the world that we are creating through our behaviour, through our politics, through our environmental priorities. To me, it’s not all done and dusted. It’s not just a matter of photographing the last parakeet in Borneo… I want the work to not just be a historical record, but to be a motivating, thought-provoking piece in the puzzle that we’re all engaged in.”

The Anthropocene Illusion is Nelson’s latest long-term project exploring the human impulses that underlie some of our most pressing sociopolitical problems. It follows his breakthrough series, Gun Nation, made in the late 1990s and exploring America’s deadly love affair with guns in the wake of the increasing prevalence of mass shootings. The multi-award-winning photo essay, book and touring exhibition marked a step away from strictly documentary work towards a more analytical approach. For his next book and exhibition project, Love Me, which debuted in 2009, he turned his attention to the global obsession with western beauty ideals, setting the blueprint for his latest series by shooting in many different countries to tell a nuanced, multidimensional narrative about a complex contemporary issue.

His project Hackney – A Tale of Two Cities (2014), was shot close to home, interrogating “hyper-gentrification” and the “bizarre juxtapositions of wealth and poverty, aspiration and hopelessness” in the borough in which he grew up and he still lives close to. He went on to make a feature-length film, The Street (2019), examining similar issues but focusing on just one east London street over a four-year period.

Nelson explains the common thread to his work as “driven by a critical interest in the intersection of modern capitalism and human psychology”. His newly completed project is no different in that it is less concerned with evidencing environmental catastrophe than exploring how and why we let it happen. But the idea for The Anthropocene Illusion was sparked a little more than a decade ago by a trip to Tromsø in northern Norway, which he was visiting to attend the opening of Love Me at Perspektivet Museum. While there he went to Polaria, an Arctic aquarium on the edge of town.

“They had a seal living in this very artificial environment under sodium lighting in a pool surrounded by fibreglass rocks,” he says. “And I found it very, very depressing. Not only because of the plight of the animal and the conditions it was living in, but the fact that here we were in the Arctic, on the northern edge of Europe, in a place actually built onto the rocks of the coastline, and there were the same creatures living in freedom just close by. I didn’t understand why that would be.”

Later, having decided to explore the question in depth and after visiting and photographing similarly artificial spaces around the world, he came to a grim revelation: “Just as we divorce ourselves from the natural world and destroy it, we do something extraordinary – we create staged-managed versions of the very thing that we’re losing. It offers us reassurance, a collective self-delusion, a mask to what we’re really doing.”

When we think of virtual reality, the images that come to mind tend towards an imaginary world mediated by technology, not the often dilapidated scenes of synthesised reality Nelson has photographed. Yet, as he shows, this illusion is more compelling to us than any science-fiction or computer-generated simulation – compelling to the point of banality. Over the course of 70 or so images, embellished with the anecdotes, quotes, facts and short texts that run throughout the dummy book, we discover a world designed to provide comfortable familiarity in its recreation of nature.

Nelson takes us on a journey that begins at Chimelong Ocean Kingdom in south China, home to the world’s largest aquarium, showing us a crowd of visitors silhouetted in front of a vast screen that provides an underwater portal to a marine paradise. We visit the Tropical Islands holiday resort outside Berlin, eerily reminiscent of The Truman Show, home to Europe’s largest indoor rainforest and artificial beach. Then it is on to Disney’s Animal Kingdom theme park in Florida with its easily digestible cartoon version of Africa, complete with “real animals roaming free” and Donald Duck in a colonial-era safari suit.

We see a picture-perfect lunch laid before us in an ‘Out of Africa champagne picnic experience’ on a luxury safari in the Masai Mara in Kenya. “You fly to Kenya, pay thousands of pounds for a curated safari, and are shadowed by a Masai warrior employed to be picturesque and give the experience authenticity, while creating a scene from a movie with an already idealised and colonial view of Africa,” Nelson explains.

We sit among the patrons at a hotel restaurant in Guangdong Province where the backdrop is a live penguin display. We get a car-seat view of Longleat, one of the first so-called safari parks to open outside Africa, and a monkey is peering through the window at us. “There’s an element of ’Who’s in the zoo?’ There’s a point where we also become trapped in something of our own creation,” Nelson ponders.

We get to be close to the most majestic of ‘the Big Five’ at The Elephant Bay Hotel in Sri Lanka. “Instagram influencers flock here to photograph themselves in the infinity pool with the elephants behind them,“ says Nelson. “The elephants are in nature, in a river, but are not free. They are part of an illusion. They are the largest captive herd of elephants in the world, and they are chained to the rocks beneath the water. Meanwhile, wild elephants are being poisoned by villagers because there’s not enough land to share.”

Nelson also takes us beyond man-made tourist destinations. We go to Singapore, known as the greenest city in Asia, with its hanging gardens and hotels covered in dense foliage. “In some ways, it’s rather beautiful,” says Nelson. “But the reality is that pesticides are sprayed three times a week throughout the city because they don’t want any insects. It’s a version of nature without reality.”

And we go to Yosemite National Park, one of the world’s first national parks, whose rugged beauty was famously captured by Ansel Adams, his photographs becoming icons for a burgeoning movement to preserve America’s wild and scenic spaces. “At the beginning, I was more focused on the artificial,” says Nelson. “But then I became more aware that even so-called natural environments are in some way so staged, managed and controlled that they become like a glass-cased museum display.”

“The reality is that pesticides are sprayed three times a week throughout Singapore because they don’t want any insects. It’s a version of nature without reality”

The pictures in The Anthropocene Illusion describe a fantasy. But it is a fantasy that only needs to hold our attention momentarily. It soon fades under scrutiny. And it becomes unsettling when we see these spaces put together in the sequence of a book; the natural utopia they are meant to evoke revealed as merely a shoddy version of reality, a poor facsimile of our natural habitat.

This is not a novel concept, as Nelson acknowledges. The book dummy is peppered with prescient citations from key thinkers from two generations past. “Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation,” he quotes from Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, published in 1967. “Everywhere animals disappear,” he quotes from John Berger’s seminal essay from 1980, Why Look at Animals?. “In zoos they constitute the living monument to their own disappearance.” Nelson’s photographs are the embodiment of Jean Baudrillard’s theory of Simulacra and Simulation (1981), which stated that, in contemporary society, “artifice is at the very heart of reality”.

Nelson also references historical antecedents to the current situation, such as his photograph of the last surviving Passenger pigeon, which died at the Cincinnati Zoo 110 years ago. It is accompanied by a short but illuminating anecdote, which ends: “Martha became a celebrity due to her status as an ’endling’, and offers of a $1000 reward for finding a mate for her brought even more visitors to see her during her last four years in solitude.”

The difference is that, while Nelson’s photographs point to an artifice long in the making, it has now become the norm, supplanting much of that which it copies. In one of the many short texts in the dummy, Nelson drops in the fact that there are now more tigers living in captivity than in the wild. “It’s great that places like Yosemite exist,” he reflects. “It’s beautiful. But millions of visitors flock there every year in their cars, and I found myself in a queue of SUVs, engines running, windows up, air conditioning on. Here humans are on a kind of pilgrimage to experience nature. The nature is real, but it’s choreographed and highly controlled. The problem is that it allows us to deceive ourselves. We get our fix of nature and go back home feeling that all is well. But, actually, nature is only out there to be experienced in these increasingly prescribed, diminishing outposts. And that is what my project is about.”