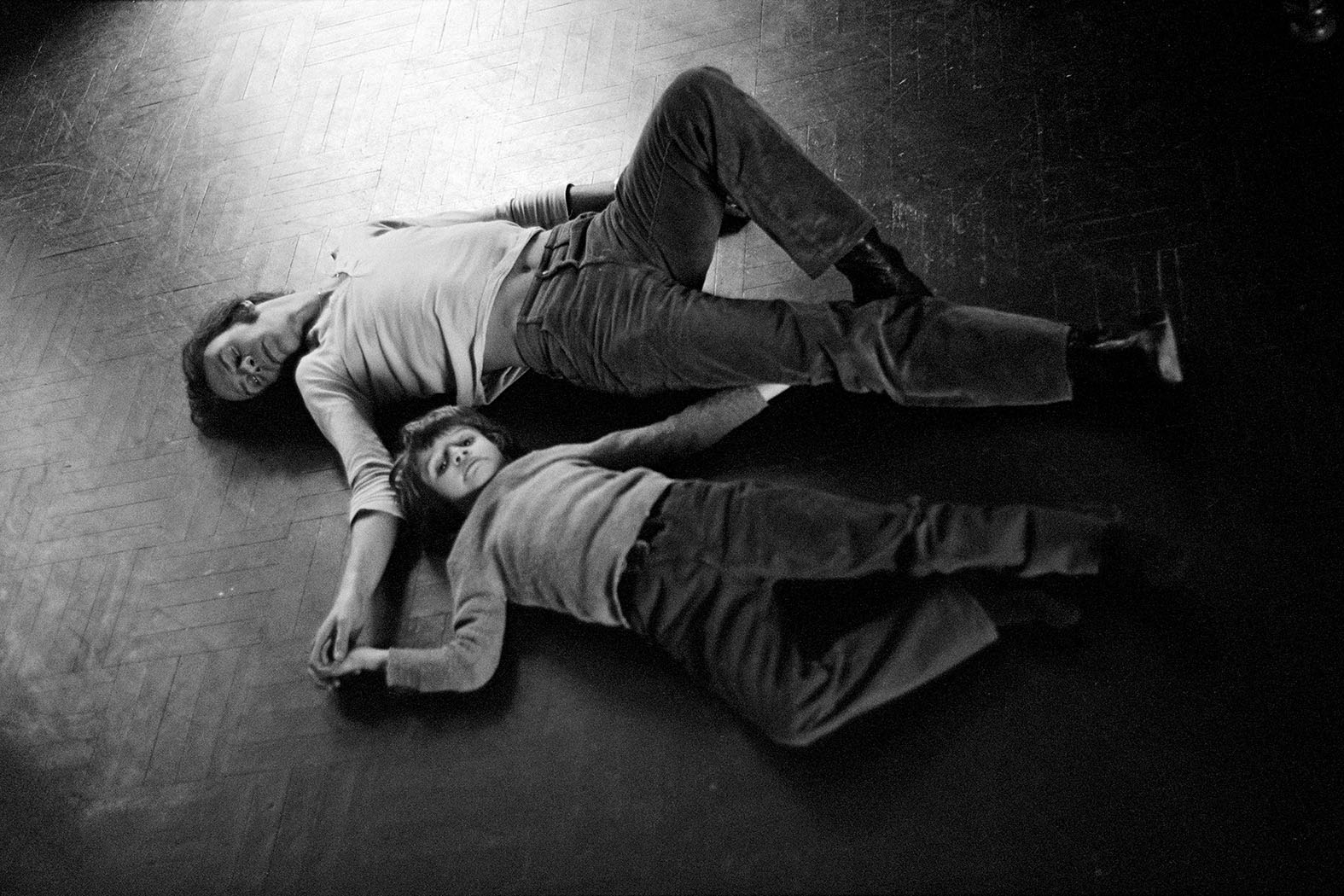

From the series Soviet Union 1991-2009. All images © Bertien van Manen. Courtesy the artist and Mack

This article originally appeared in the Who Am I? issue of British Journal of Photography (November 2014). It is being republished on the occasion of Van Manen’s death on 26 May

In this profile from 2014, the late Dutch photographer discusses her Cold War travels, influences, and Roman Catholic upbringing

In the small, unassuming town of Landskrona, in southern Sweden, Dutch photographer Bertien van Manen takes to the stage. Nervously clearing her throat she quietly talks through her work, outlining projects she’s worked on for years, often showing her close family and friends.

She cuts a distinctive figure, though – a lean woman, elegant woman with a flame of red hair – and the audience hangs on her every word. She’s also been invited to speak by revered Swedish photographer JH Engstrom, who, together with the artistic director Thomas H Johnsson, has curated this small, intimate photography festival. Now in its second year, the festival features Nan Goldin, Rinko Kawauchi and Margot Wallard, among others: Engstrom was already an admirer of Van Manen’s work, but was pleasantly surprised to meet – and teach – her at a workshop in London a few years ago.

At a press conference for the festival, Engstrom was asked why he included van Manen, and replied, “because her photographs are warm”. Asked why they are warm, he replied “because they are”, summing up the difficulty of translating images into words. Photography is its own language, and trying to describe it can be like listing the ingredients of a good meal – semiotics cannot describe the feelings that photographs can evoke, just as taste cannot be savoured until the food hits the mouth. To over-intellectualise is to dull the emotive flavour.

![Bertien van Manen, I will be Wolf (2017). Courtesy of the artist and MACK. [2]](https://www.1854.photography/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Bertien-van-Manen-I-will-be-Wolf-2017.-Courtesy-of-the-artist-and-MACK.-2.jpg)

In van Manen’s work, that emotion is unmistakable, in vital images that are at once considered and free, shot with empathy for her subjects. Conveying this warmth is a feat in a medium that essentially objectifies reality; it’s a creative ability that takes root at an early age in the lucky few, nurtured by the stark realisation that willpower is all that stands between shaping their lives and falling victim to circumstances.

In van Manen’s case, she was motivated by the desire to escape her stifling and conservative “upper-bourgeois family”. Her bid for freedom was compounded by rebellion against her strict Roman Catholic education, which she later described as trying to break her will. Years later, while shooting a project on pilgrimages, she felt compelled to photograph a priest laying his hand on a young girl kneeling before him because “it reminded me of these priests when I was at boarding school, and how macho they were and how they tried to put you down as a person with their power and hypocrisy”.

Independent ground

The writer William Burroughs once stated that “the first and most important thing an individual can do is to become an individual again, decontrol himself, train himself as to what is going on, and win back as much independent ground for himself as possible”. As a young mother in the 1970s, juggling home life with a thirst to realise her true potential, van Manen needed wilful determination and tenacious courage to succeed. She photographed her immediate family to make the images that became, many years later, the book Easter and Oak Trees (2013), an intimate black-and-white series that conveys a mother’s perspective as she watches her children, naked and running wild, evolving into self-conscious teenagers posturing in flared trousers and floppy hats.

Unlike the beautifully considered work of Sally Mann or the brooding Nordic feel of Margaret de Lange’s images, van Manen’s aesthetic is sketchy and spontaneous, but her sensitive eye makes this collection much more than a family album. With it she clearly laid down the template for her approach, seeing the extraordinary in the ordinary, without the temptation to exaggerate. The book was published shortly after her husband passed away, and serves as a loving appreciation of the family she built with him and an acknowledgement that she started out photographing those closest to her. Our identities are built from memories after all; van Manen believes “you do not need to show yourself because your photographs already possess the capability to do this”.

By the early 1980s, van Manen was working as a fashion photographer but had an epiphany when she came across Robert Frank’s seminal photobook, The Americans. His scratchy and imperfect compositions, outsider perspective, and apparent freedom of style inspired her to move in another direction and she started working as a photojournalist for Dutch publications such as the now-defunct Avenue. But she soon realised she wanted to make a different kind of image, taking her time and getting under the surface of things rather than jetting in and out.

![Bertien van Manen, Beyond Maps and Atlases (2016). Courtesy of the artist and MACK [2]](https://www.1854.photography/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Bertien-van-Manen-Beyond-Maps-and-Atlases-2016.-Courtesy-of-the-artist-and-MACK-2.jpg)

“I am guided more by a feeling and a search, a real longing, for some kind of meaning”

She started travelling to make her own projects, working slowly over years, decades. Her series – A hundred summers, a hundred winters (1994), East Wind West Wind (2001), Let’s sit down before we go (2011) and Moonshine (2013), among others – can perhaps be described as ‘private documentary’, searching projects that enter into closed cultures and societies to photograph people seemingly far from her own experience with an intimate, curious eye. The people she shoots and befriends are also much wilder than those she grew up with, something she says is “totally to do with the opposition to how I was brought up in my youth, being suppressed and always being the good girl”.

East Wind, West Wind is a non-political venture into Communist China, for example, made well before the country opened up. It took a few visits before she understood what she was looking for, although she finds this is often the way; delving into the hidden recesses with highly saturated colour, she revealed as much about the Western audiences’ limited perceptions as what she saw.

For Let’s sit down before we go she ventured into the post-Soviet countries of Moldova, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, Georgia and Russia, taking her title from a Russian maxim advising travellers to stop and think before starting their journeys. Van Manen first visited the USSR in 1988 but says it was impossible to start the project then; in order to have the freedom and acceptance she wanted, she learned Russian and revisited the region again and again over 18 years. The resulting book was edited and sequenced by British photographer and independent publisher Stephen Gill, who, she says, “seriously spent time organising my work”.

Restless eye

Milan Kundera’s book Slowness extols the virtues of being slow in our age of speed: the novel starts with the narrator and his wife driving sedately through the night through France and being dazzled in the rear-view mirror by an impatient motorist attempting to overtake. The moral of the story is that the faster we go, the less of life we see and experience. There is nothing unique in this insight, and yet it’s so obvious it’s often overlooked. Depth and meaning can take time to emerge, as van Manen’s latest book illustrates. Moonshine was published in April this year, but van Manen started working on it back in 1985, originally conceiving of it as a project about female miners.

She was drawn to the so-called Hillbillies in the Appalachia of Kentucky, Tennessee and West Virginia – a group famed, and stereotyped, for their illegal whiskey distilleries. In particular, she was drawn to a woman called Mavis, who lived with her husband Junior and their children in a trailer on a mountain in Kentucky. In Moonshine, van Manen shows the course of Mavis’ life as she loses Junior to cancer, loses her job as a miner, remarries and sees her children grow up – all against the backdrop of the crumbling, coal-mining community. The photographs ride with the chaos, recording the extended family, the children, guns, cars and affection that make up the everyday fabric of this way of life. Moonshine bears testimony to human connection, as exemplified by Mavis and van Manen’s enduring friendship, despite their very different backgrounds. It also reveals the intimate life of a family against a changing culture and society.

“I am very restless, if I do not do this I feel I will die,” van Manen tells me over the loud drunken sounds of a Swedish bar. Her comment prompts me to ask how the death of her husband has affected her, whether it has changed the way she works. “When he died it was not an immediate blow, but it has worked slowly on me,” she says. “I have started a new project on the western coast of Ireland; I have been there four times already. It is to do with death, but I am not quite sure what I am looking for – I am guided more by a feeling and a search, a real longing, for some kind of meaning.” [Van Manen eventually published this work with Mack in 2016, titling it Beyond Maps and Atlases].

The light and the atmosphere in this region is very special, and for van Manen there is also mystery at the edge of a land beyond which is only a vast expanse. It is, perhaps, an apt metaphor for her work; photography can be a tool to encounter life, to engage with it and to try to come to terms with it, in the process of doing, in moving towards the beckoning light.