All images © Alice Zoo

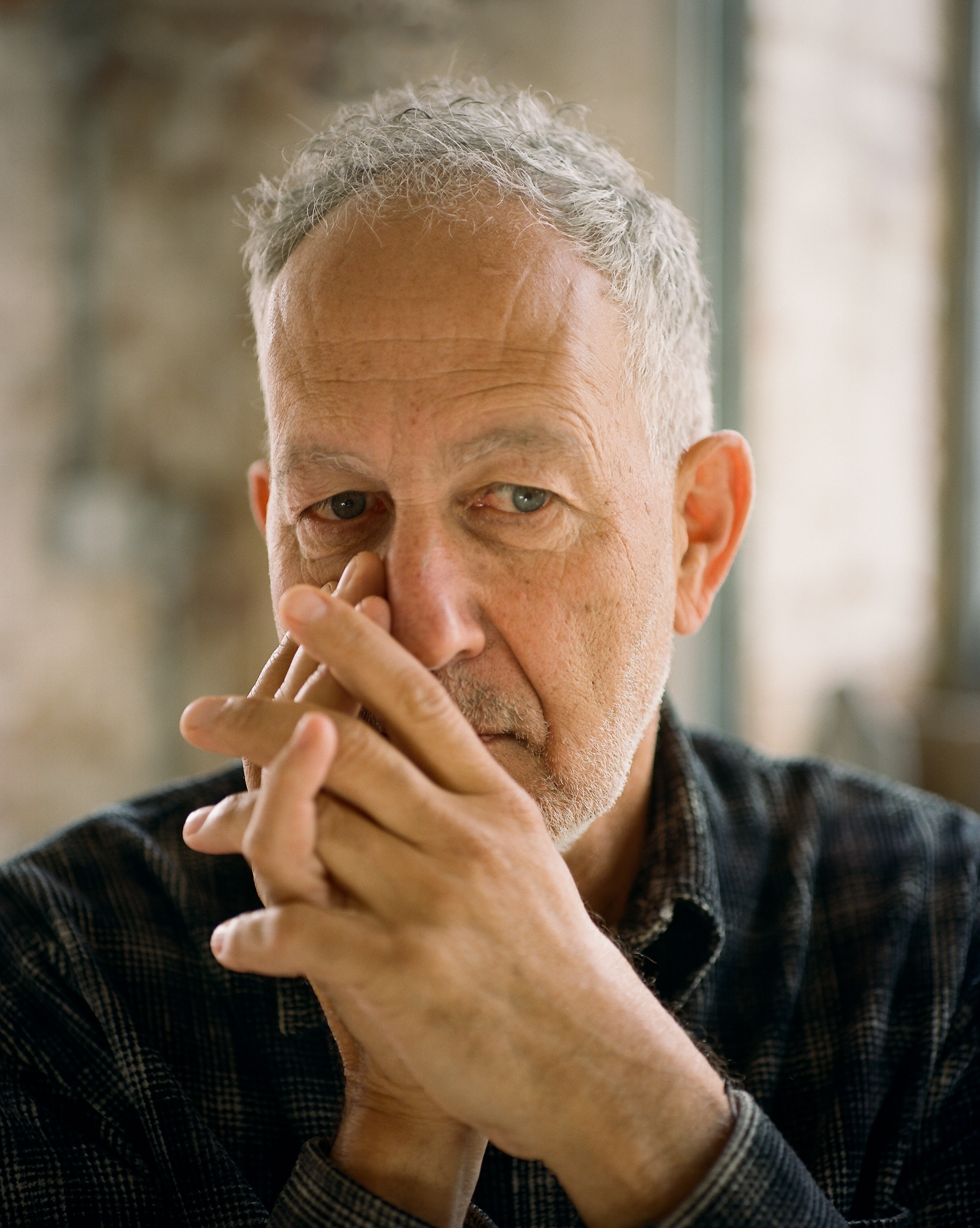

Known for his portrait and landscape work, Kander has a meditative approach in his London studio – and a profoundly subjective take on making images

Nadav Kander’s Kentish Town studio is bright, with windows on two sides of a large room, its walls made of pale, exposed brick. The feeling is airy and spacious, the surfaces clear. Around the edges, every bit of storage is used to its maximum, the inbuilt shelves dense with boxes of prints, the windowsills adorned with curiosities and ephemera – figurines, souvenirs, a tiny row of books, miniature prints on easels.

A tall, double-sided bookcase is filled with an extensive collection of books, on painting, music and architecture as well as photography. Kander’s dog, Juno, lies on a red cushion at his feet, and a taxidermy crow is perched on the desktop monitor. At the crow’s feet stands a model Nadav Kander, a homunculus 10 centimetres tall. A quote from Diderot is Blu-Tacked to the computer on Kander’s desk, reading “Everything comes to nothing, everything perishes…”

Kander arrived in this studio in 2003, and it was here he developed the work for which he is best known: Bodies. 6 Women, 1 Man; Dust; the Prix Pictet-winning Yangtze – The Long River; and more recently Dark Line – The Thames Estuary. At first his work here was divided between two floors, Kander editing downstairs and photographing upstairs; four years ago, he moved the whole operation upstairs. He speaks of an almost ceremonial connection to the place and his rituals there, especially his work downstairs, “facing south, in a certain part of that studio, with a certain feel of the desk”.

The ritualistic process, the creation of the specific, finely calibrated conditions that would provoke the right mindset for the work, was especially defined while he was working on the Thames. “When I made the work on the estuary, I would always arrive in the darkness, onto the river, and I would always leave in darkness,” he recalls. “Somehow I never wanted to see real England as I arrived, I wanted it to remain quite mystical.

“When I made the work on the estuary, I would always arrive in the darkness, onto the river, and I would always leave in darkness”

“And when I did the printing on my computer, and all the relooking at the work, I always came in at three, four, or five in the morning, and would finish by nine. It was always done pre-light, with certain styles of music playing that were quite evocative, and quite dark.” (Nivhek’s After its own death, for example) “I kind of fell in love with that space, and the music, and the early mornings, and very exciting pictures. Because I love the estuary work: I think it’s almost the best work I’ve ever done. It’s the most my work.”

Kander was struck by the bleakness of the estuary when he first went to see it. “I came back a bit dejected, and started making a scrapbook of how other people had seen the estuary, like Whistler, or Constable,” he says. Having primed himself with these other interpretations of the river, he was able to see it differently. “It was like I was looking at water that had almost been exhausted,” he recalls. “It’s slowing down, it’s widening, and it’s ready to meet its greater whole, the ocean. It’s like the end of life, in a way.”

For him the river became a moving testament to the “unbelievable human history” it has witnessed on its endless journey through London. “I decided to keep that idea of Constable writing there, unbelievable voyages, people’s loves lost, ships never returning, wars fought,” Kander says. “And all of this humanness I decided to keep with me in my scrapbook, in my mind, while I photographed.”

Working on the images in-studio required another kind of layering, with the river’s manifold pasts and histories invoked by involved work on the prints, finessing colour and tone. “The estuary was quite particular in its made-ness,” Kander says. “What you’re looking at is so bleak, and I wanted them to have a feeling that you’re standing in front of a Rothko.” To make these very particular prints, reflecting such breadth of feeling and experience, his approach in the studio had to reflect his journeys to the river itself.

“I needed to almost begin again, feeling the same feeling, which is why I would come at night,” he says. “I would try to make these works feel like I feel. And that needed layering of colour, or flattening of parts, taking away information where it’s not needed, and really getting into printmaking.” For Kander, the process was a kind of meditation, “my favourite meditation”.

When the work was exhibited at Flowers Gallery in London, Kander included a moving-image work, scored by Max Richter, which showed him sinking and rising beneath and above the diaphanous surface of the Thames, all slowed to half-speed. The film helped guide the viewer’s experience of the photographs. “I was talking about the river in old age, softening, darkening, and beginning to die, beginning to be absorbed, and if you would like to think Jung, or Buddhism, you might think evaporate and start again,” Kander says. “I wanted the exhibition to become clearer, what it was that I was authoring.”

The exhibition asked for more from the viewer than simply contemplating exquisite prints for their aesthetic appeal. “You were here to invite yourself to feel rhythm, to feel tide, to feel this natural phenomenon that is around us, which for me was – is – what this work is about. Being born and dying, another rhythm. And the beauty in that, and the softness of that.” In the film, Kander’s hands are gently placed above his heart, his eyes closed, face relaxed into a mild and beatific smile. Pulled below the surface, he turns his head, opens his eyes, and looks towards us through the water. Some people left the installation in tears.

This clarity of intent is an absolute priority for Kander. “I’m only really interested in work that shows clear authorship,” he says, work that “really shows the person behind the camera”. “I remember clocking that when I was a kid, looking at Edward Weston’s work,” he recalls. “He could show a nude that looked like his portrait, that looked like his shells, that looked like his toilet bowl, his pepper. I remember thinking, ‘Five different subject matters, and they all are his’. That was authorship.” Kander pauses. “I’m not from the camera club who wants to print exactly what the film has – that’s not what it’s about for me. I’m much more about how you feel about the shape and colour.”

“Making a story is a bit like Ian McEwan writing a story. He’s telling a story but really it’s the reader who becomes energised by that, and makes up their own love affair with that book”

He is frustrated by the narrative around photography, that the medium is truthful, accurate, and somehow objective. “I’m sick of that old school hanging on to reportage, or documentary, and ‘storytelling’,” he says. Kander believes photographs are as subjective as the paintings and poems he frequently references – in the course of our conversation he mentions Francis Bacon, Marcel Duchamp, Michaël Borremans, Léon Spilliaert, John Constable and Dorothea Tanning.

“I don’t photograph to tell stories, I photograph to make stories,” he says, quoting from the introduction to his most recent monograph, 2019’s The Meeting. “Making a story is a bit like Ian McEwan writing a story. He’s telling a story but really it’s the reader who becomes energised by that, and makes up their own love affair with that book, or how they envisage it. And it’s true of poetry too, everybody has a different take on a poem. It’s well-known that if you read one, and I read the same one, you might have a very different feeling than me. But photography somehow isn’t seen like that, and that frustrates me.”

This insistence on clear authorship is intuitive enough for still lifes or landscapes, in Weston’s pepper or a river’s widening mouth. But Kander applies the same framework when making portraits. Ahead of a portrait session he considers ‘How would I show this face if it was a dummy? A Madame Tussauds rendition of the person?’; he also Googles his subject, meticulously plans the lighting, and rehearses so that he and the person can work together to transmit a concentrated, potent and specific feeling. Counter to the way many approach portraiture, for Kander, the subject’s own subjectivity is not quite the point. Instead they become an actor, a conduit for something elemental.

The right atmosphere

“I’ve been jealous of Francis Bacon for a long time, in that he could be in his studio early in the morning, on his own, with his music, cigarette, drugs, whatever, and he would paint from a photograph. He never painted from a person sitting in front of him,” says Kander. “It would be so amazing to not have the person there, who has their own agenda. I’ve got my own baggage, too, I might feel intimidated. I wish I could go and push a mole and they’d just keep quiet for a while!

“People commonly think of a portrait photographer, like myself, making my sitter feel very at ease,” he continues. “Talking about how their day has been, so that they become relaxed in what to many people is quite a terrifying experience. A lot of people feel very looked at, very seen – it’s a sustained stare. I find that curious. The great portraits that everybody knows and looks at, right back to Rembrandt’s self-portraits, where are the great ones where people are super relaxed? Look at Irving Penn’s portraits, they have energy and tightness. If you’re going to believe in the meeting being truthful, being a true, unmanipulated encounter, then why would I try and interfere with how a person really is?”

It is true that the prevailing narrative around portraiture seems to seek to deny the camera’s presence – to coax naturalness, ease and a lack of self-consciousness from a situation that is anything but natural. “Putting people at ease is very overrated,” says Kander. His approach is predicated on the artifice of the scenario, the camera, the photographer, the lights. It is akin to the way the artificial setting of a theatre allows actors to present a concentrated version of human stories and emotions and, thus contained, the audience is able to look past the artifice and lose themselves.

Considered response

Kander has a marked determination to hold a space for tension. In conversation he is conscious and exacting, sorting through words until he lands on exactly the right one. At times he stops before a sentence has had a chance to gather pace and pauses to think, completely motionless, as though time is suspended for a moment. His photographs work similarly. They are poised, often melancholic, and profoundly stilled, as though it were life that had stopped the person’s motion, not the action of the shutter.

“There’s some otherness in me that craves a certain uncomfortable look at things,” Kander reflects. “Slightly uncomfortable but beautiful. A bit like putting mustard on chocolate cake.” A Jungian might call this otherness the shadow, the yearning towards the unconscious darkness in all of us, the undiscovered, the unresolved. “We all crave it in a way,” he continues. “That’s why none of us go to movies that show people relaxed, having a nice time, smiling and holding hands.”

I ask him about this inclination. Does it arise from the heart, or from the intellect? “When one is attracted to a great photograph, or great painting, or a great poem, it comes from feeling,” he says. “When I’m making a portrait, it’s the absolute highest percentage of feeling compared to brain. It’s almost entirely feel.” I begin to wonder about the studio as a kind of therapeutic space, in which feeling is brought up from the depths of the unconscious to be condensed and, ultimately, fixed in a photograph; the lights and gels bringing up the shadow, whether it be Kander’s, his subject’s, or that of the viewer. “Most of the pictures I’ve taken,” Kander says, “have been without much consciousness of my process at all.”

Jung dreamed of consciousness as a house, the conscious mind as the higher floors and the unconscious down lower, on the ground floor, and then deeper still into the basement. Perhaps Kander’s studio is like a therapy room, but perhaps too it is like walking into his mind – a first impression of space, the profusion of tiny personal effects like the personality dotted across its edges. The decades-long archive filed into drawers like memories, the heavy machinery hidden behind a curtain, and downstairs newly inaccessible, consigned to the past.

“Probably the main way that [the studio] has informed me is that the mood of how and where I work changed in 2019,” Kander says. “When I came upstairs it was just pre-Covid, then right as it all happened, I was moving up. So I hadn’t been here that long, and I’m still getting used to the space.” His new desk faces the same direction as before, although it is a floor higher – he has ascended, and is newly distant from the depths of his first workspace. “I’ve never delved as deep as I did when I first did the estuary,” he says. “I’ve still got that goosebumpy time of four in the morning downstairs in my head. I haven’t experienced that upstairs yet.”