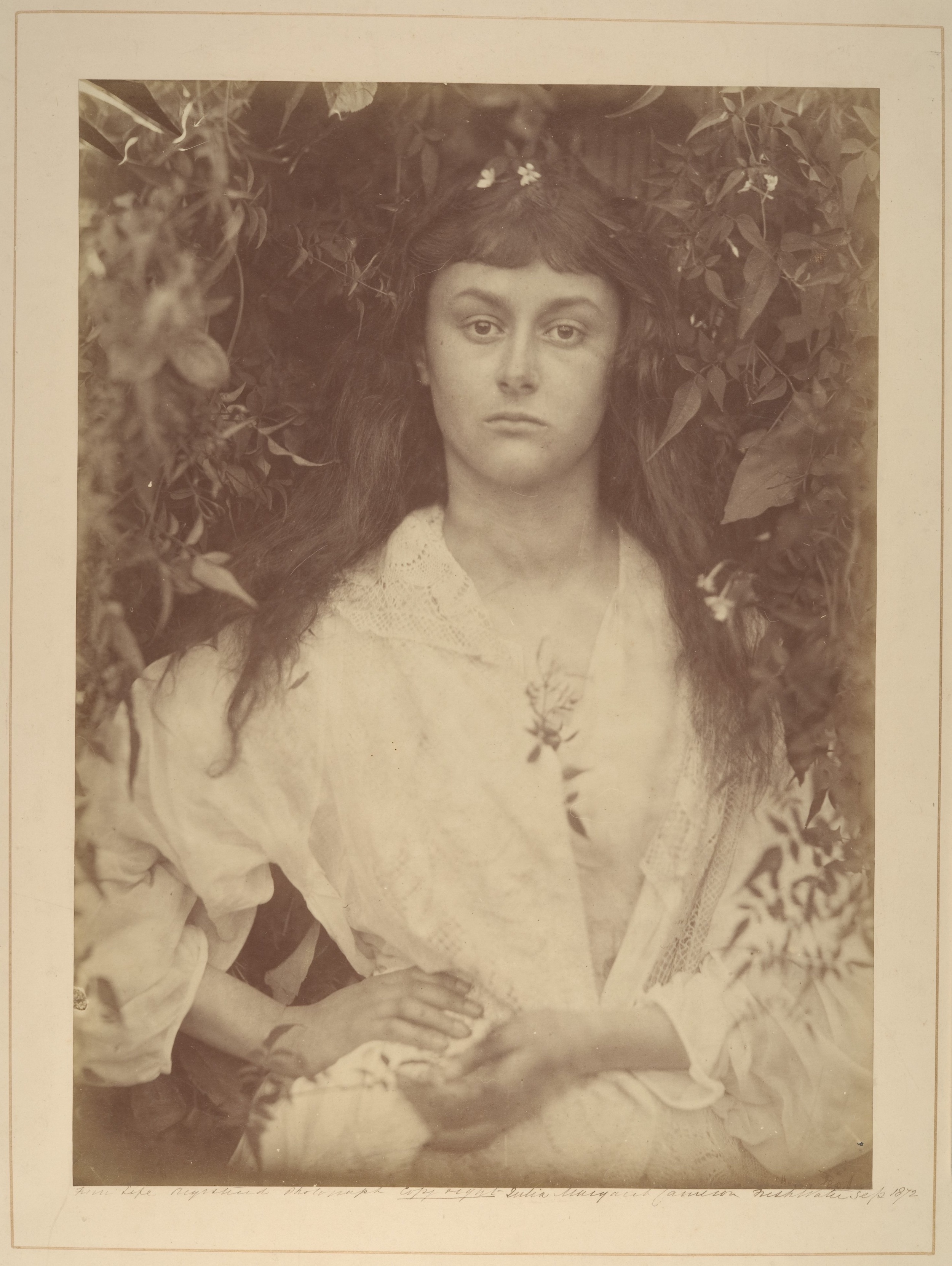

Pamona (Alice Liddell) by Julia Margaret Cameron, 1872. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, David Hunter McAlpin Fund, 1963.

In a new exhibition the National Portrait Gallery, the of works by Julia Margaret Cameron and Francesca Woodman are brought together across time and space

Between 1866 and 1868, Julia Margaret Cameron made a portrait of Mary Pinnock as Daphne, the nymph who was transformed into a tree to escape the clutches of Apollo. In 1980, Francesca Woodman made a series of images of herself amongst trees, or partially wrapped in tree bark. They are untitled, but hung beside Cameron’s Daphne in the National Portrait Gallery exhibition Portraits to Dream In, they prompt the viewer to read the ancient narrative into them too. Curator Magdalene Keaney calls this a “proposition”, and it’s one of four she has created by hanging Cameron’s mythical portraits alongside a group of Woodman’s works. The subjectivity of these comparisons exemplifies the ethos of the exhibition, which brings these two photographers together across time and space.

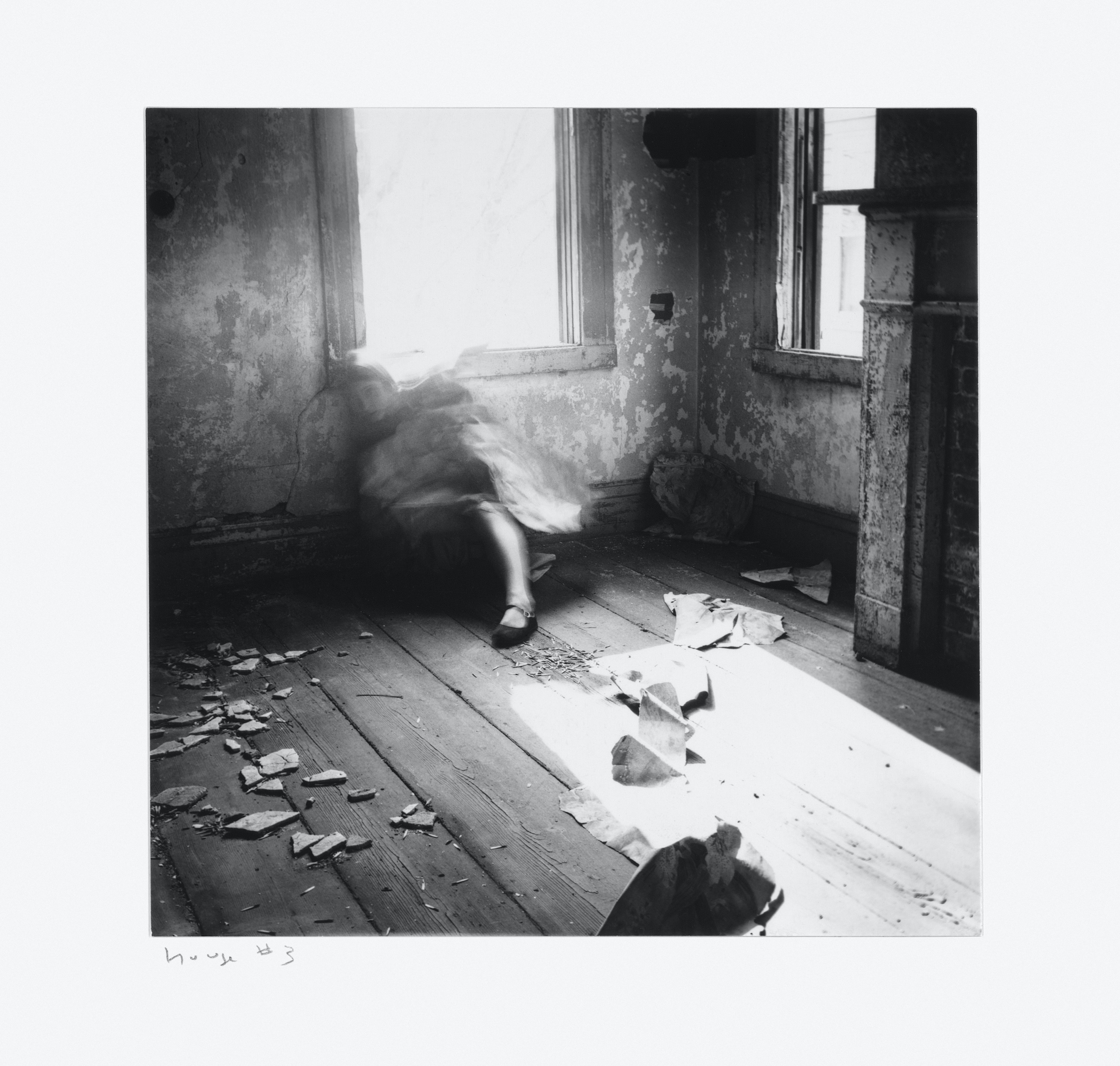

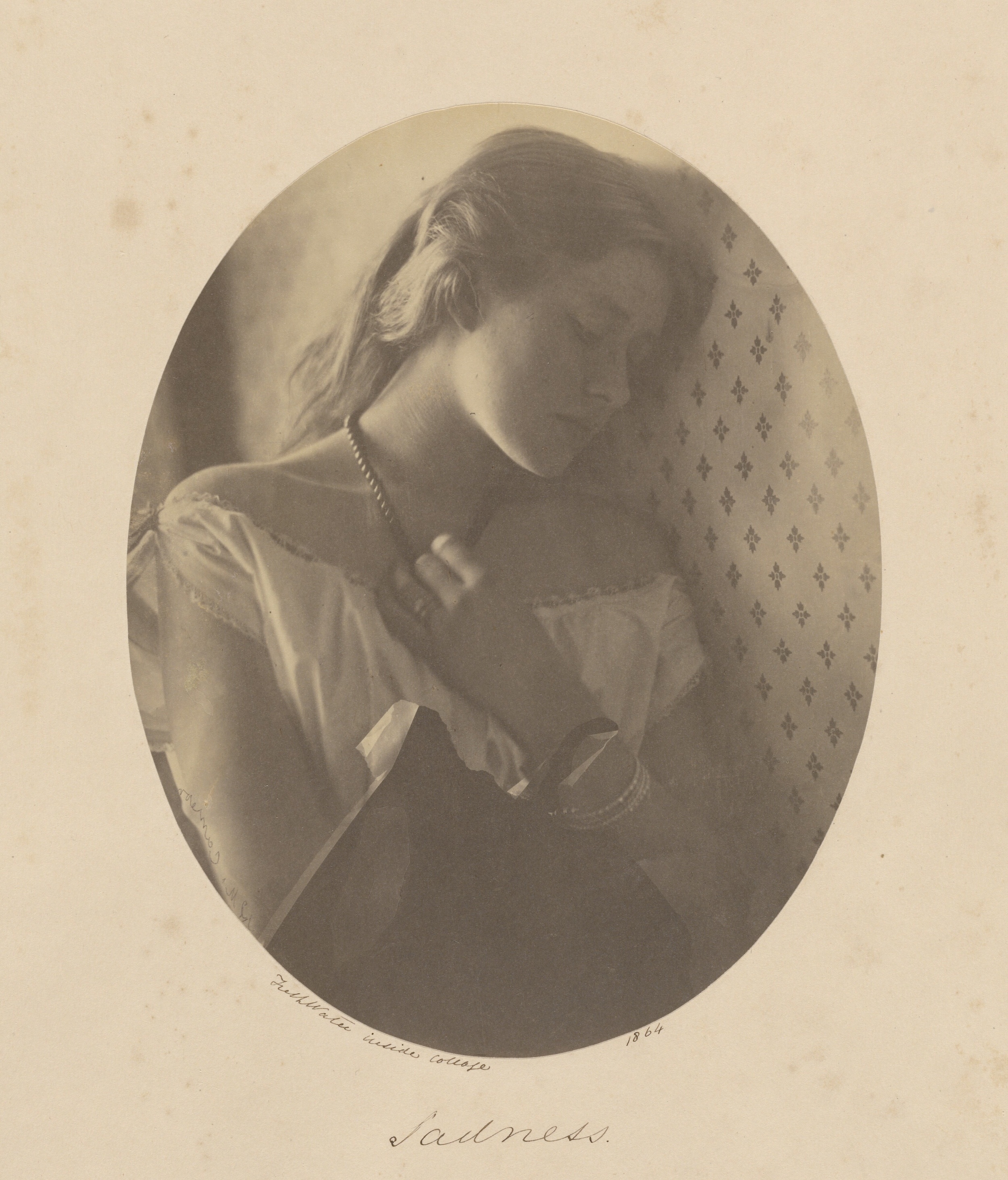

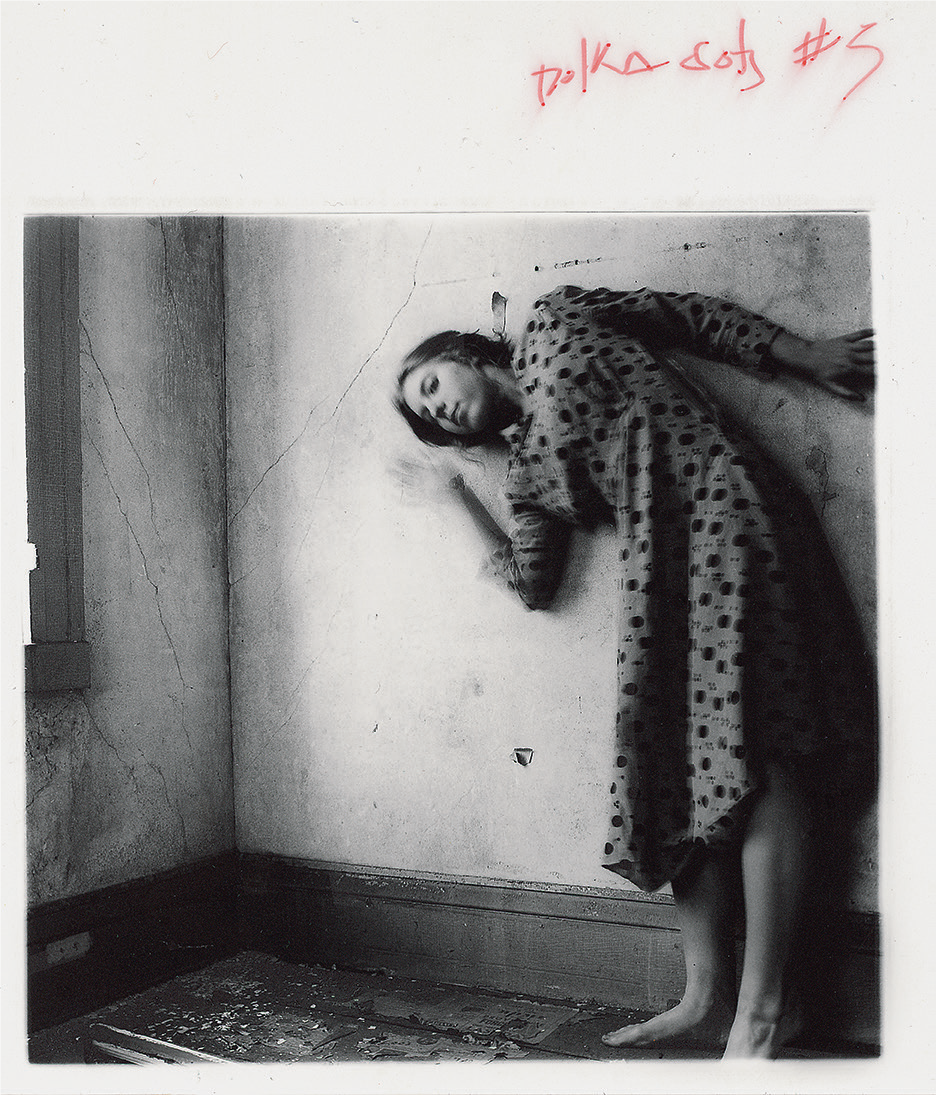

Portraits to Dream In is remarkable in that it explicitly rejects biographical readings of these artists and their work, readings which often swallow the appraisal of art by women. The formalism that guides the installation pairs works that look similar, sometimes explicitly, as in a salon-style wall filled with images of angels and angel-inspired figures, and other times less tangibly, as in a pairing of Cameron’s Sadness (depicting Ellen Terry leaning against a wall with a dotted wallpaper) and Woodman’s Polka Dots #5, which features a figure in a dotted dress. Looking at the dotty images together, I noticed elements of each I hadn’t before, and felt confidently steered by an unusually evident curatorial eye.

All the works featured are vintage prints, including the epic large-scale Caryatid series by Woodman and several of her scrapbook-like artist books, facsimiles of which were recently published in Francesca Woodman: The Artist’s Books. Many of Cameron’s prints retain the irregularities and interventions characteristic of Victorian photography, and the traces of the artists’ hands throughout lend a strong haptic quality to the exhibition.

The serious engagement with these works is commendable, and the fact that this is even notable points to the way the work of both artists has sometimes been dismissed as unserious or too ‘pretty’. But for me, the erasure of the individual artists’ lives goes too far. Both artists are remembered after careers that were limited by time and circumstance, making it important to acknowledge why their work has endured. Both Woodman and Cameron were wealthy, well-connected white women who made images compatible with mainstream expectations of femininity. Woodman in particular is having a moment; it’s not undeserved, but it’s also true that she died aged twenty two, frozen in time as an artist onto whom gallerists, collectors, curators, and viewers can project their desires.

The facts of both women’s lives also run through the fabric of their work. Woodman’s Caryatid series, for example, is juxtaposed with Cameron’s Studies After the Elgin Marbles; both evidence a deep familiarity with the art and architecture of antiquity and with Western museums, and the upbringing and education that provided it. The subjects of their photographs – Cameron’s family members and illustrious, cultured friends, and Woodman’s peers at the Rhode Island School of Design – show the circles in which they moved.

Woodman began taking photographs as a child, encouraged by her artist parents, and continued until her suicide in 1981; Cameron was introduced to photography in 1849, when she moved to England aged thirty four. She continued until 1875, when she and her husband permanently moved to Sri Lanka, then British Ceylon. Cameron’s work is distinctly Victorian British; it is the product of Empire, specifically of an artist whose family was embedded in the economy and bureaucracy of British colonial India.

Identity-oriented curating can and often does go too far; many exhibitions about women artists centre on the fact they are women. By contrast this exhibition is bold, setting out a new paradigm of looking at art transhistorically, formally, and without preconceptions. But for me, removing the baggage of actually being alive forces us to read only ethereality, whimsy, and imagined narratives in these works. The messy complexity of living is obscured, despite also being so present in these two bodies of work.

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron Portraits to Dream In is at the National Portrait Gallery, London, until 16 June