All images © Phoebe Somerfield

From Sheffield to Peckham via Japan, the artist is tireless in his search for life in all its complexity. His next journey is to the heart of ‘future nostalgia’. We catch up with him at his London studio

When Johny Pitts left school, he worked at Debenhams in Sheffield’s Meadowhall shopping centre, stacking and occasionally selling crockery. It was not long before he was sacked for breaking too many plates. Embarrassed to tell his mother, he pretended he still had the job, leaving the house on shift days and wandering aimlessly through the city. He would venture south from Firth Park towards the industrial districts, tracing new routes to his favourite record stores. The days were long and grey, his journeys anonymous.

“A midweek afternoon is a very specific atmosphere, when everybody else is doing something and you’re not,” Pitts says. There is a similar mood the day I visit his south London studio, a tepid early afternoon in July. Rain falls onto the skylights as Pitts flicks through plastic wallets filled with old CDs. He quickly finds the one he is looking for – a 1997 soul album called Spirit Tales by Swedish singer Stephen Simmonds. Pitts bought it from the bargain bin of Record Collector, his favourite of Sheffield’s music shops, on one of his post-Debenhams meanders. The cover shows Simmonds wearing a slim-fit, ribbed sweater in front of a blurred background, possibly a storefront or moving train. In another picture inside the liner booklet, Simmonds walks away from the camera down an illuminated tunnel, the edges of his dark coat forming a skirt-like silhouette.

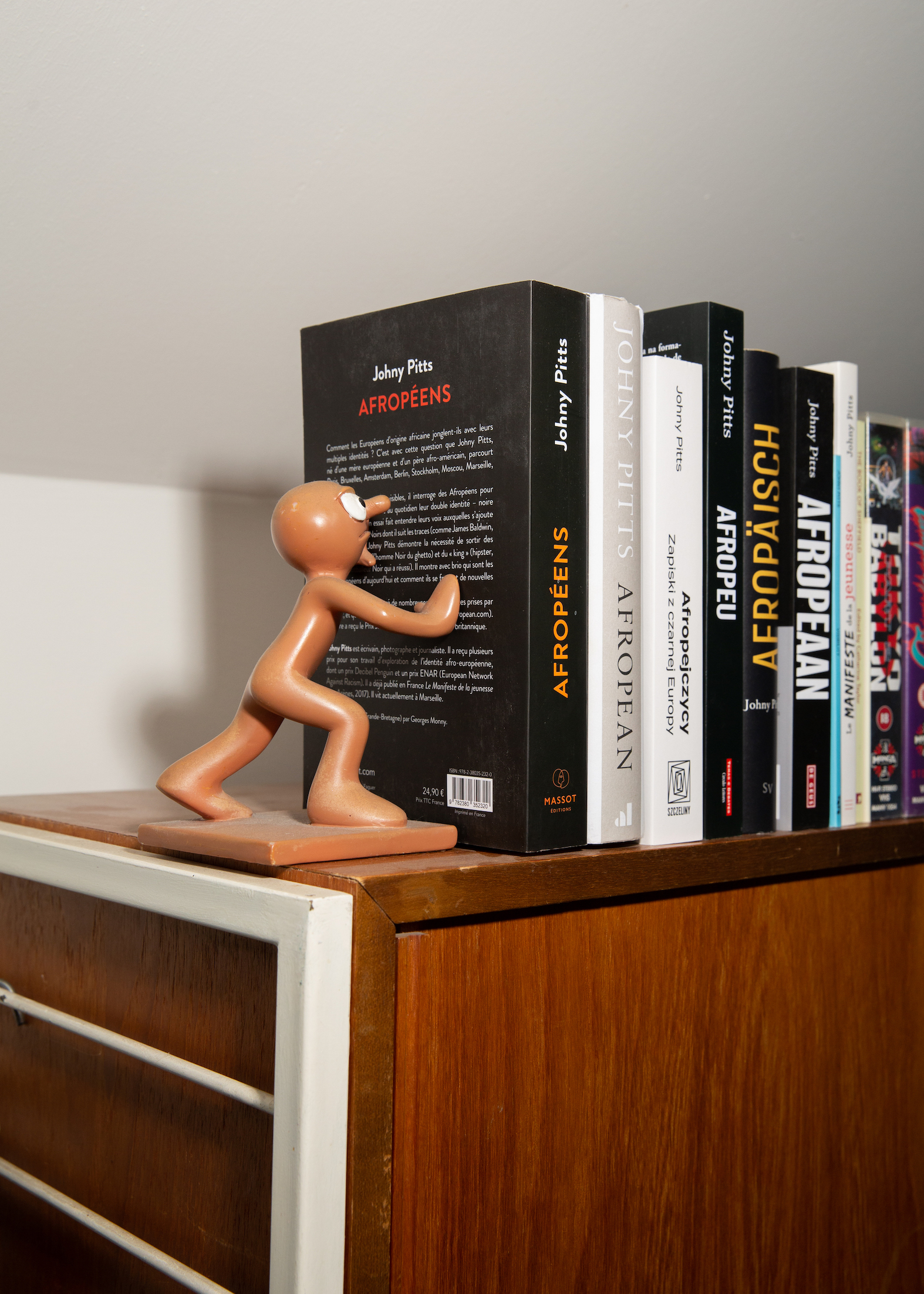

“Before this, I had never seen a Black man in these Scandinavian settings,” Pitts tells me. He became obsessed with the imagery – the juxtaposition of person and place, and the shoot’s distinct luminosity. The cover is now enlarged and framed on Pitts’ studio wall, next to a handwritten note by Amy Winehouse and a James Barnor photograph of Mike Eghan at Piccadilly Circus. The room is small, but suits the array of kit, pictures and books that cover every surface. Spirit Tales is an important artefact for Pitts, not because it sparked an interest in culture clashes, music, or even photography, but because it synthesised the unusual circumstances of his upbringing (in which these themes were already bubbling) and pushed him beyond them. When Pitts moved to London, he reached out to Anna Bergfors, who shot the Spirit Tales record cover. She quickly became a friend and mentor. In the acknowledgements to his first book, Afropean: Notes from Black Europe, he writes that Bergfors “has inspired my photography more than anyone else”.

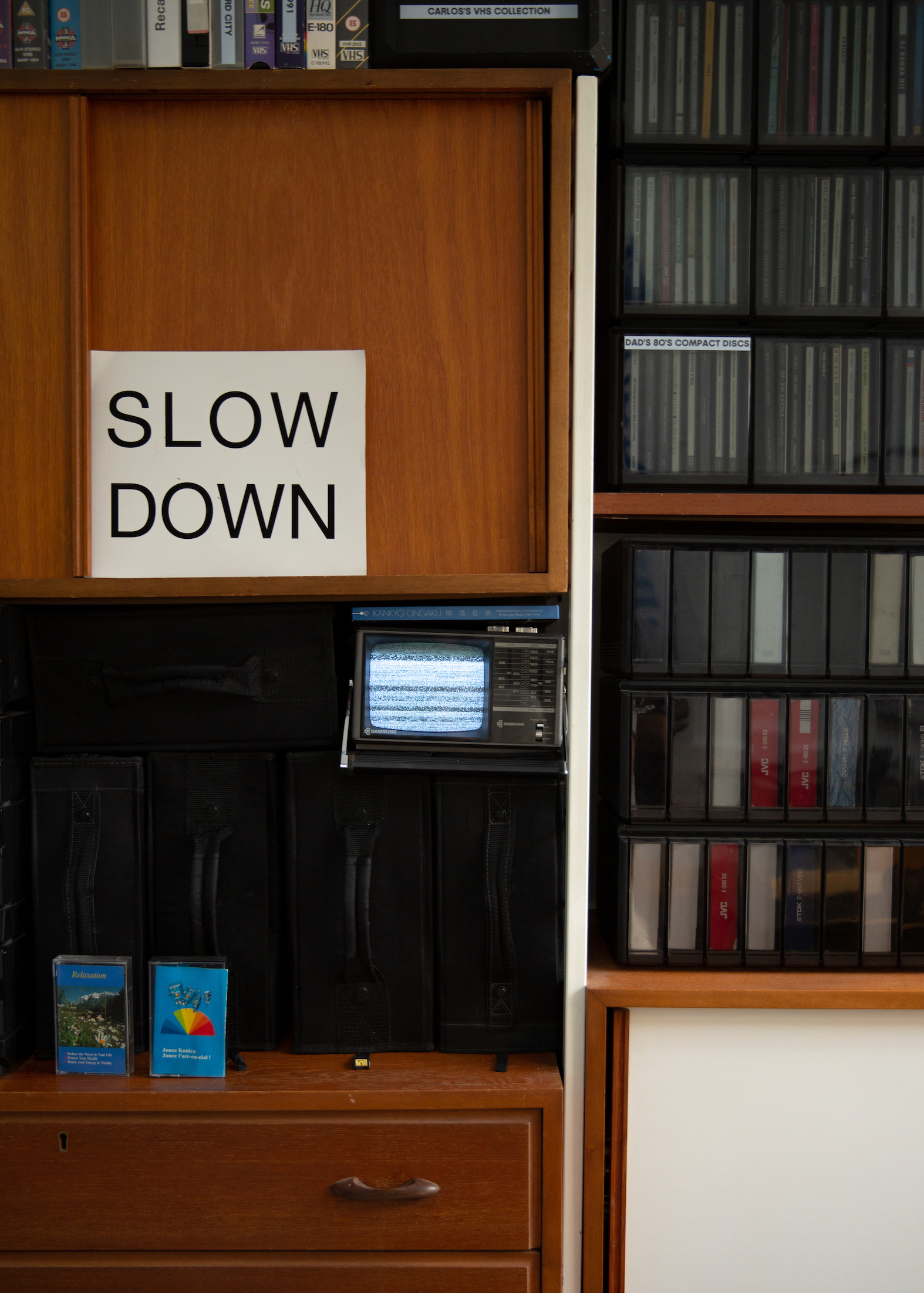

Born in working-class Sheffield to an African American father and English mother, Pitts had already spent two years living in Japan by the age of 10, transported from the world of Northern Soul to Tokyo’s late-1980s bubble economy. His childhood home contained Buddha statues and the latest Japanese tech alongside Spike Lee movies – a unique cultural mix for the time. Pitts gestures to the stacked shelves behind him, filled with VHS tapes and drawers of negatives. Ambient music plays from his dad’s old analogue hi-fi. “This space is literally my family’s archive,” he says. “There’s nothing whimsical in here.” He returns the Simmonds CD to its sleeve.

Pitts is a photographer, writer and broadcaster. There is room for one more descriptor, but it is more difficult to settle on. He wrote in Afropean’s introduction that the book was an attempt to “use on- the-ground travel reportage as a way to wriggle free from the pressures of theory”, so ‘theorist’ is not quite right. ‘Researcher’ sounds a little dry; ‘thinker’ a touch lofty. Nor does he want to be known as a mouthpiece for the Black community, a concept he is at pains to expand. The window sill in front of Pitts’ desk acts as a bookshelf: I can spot photographic theory alongside Mark Fisher, a cluster of titles about the future, and books on J Dilla and Kraftwerk. He reaches for a quote by writer DBC Pierre: “Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.” Perhaps ‘artist’ will do.

“The idea was to find a home for the diaspora – a space of consolation for the Black community, rather than for the art or literary establishments”

An Afropean flâneur

With his Afropean blog and book, Pitts sought to “honestly reveal the secret pleasures and prejudices of others as well as myself… learning to be comfortable with being Black and imperfect”. Inspired by the flâneur figure, he self-funded a hostel trip around Europe in search of disparate and unstoried Black communities. The chapter names reveal the journey’s scope: Germaica; Strangers in Moscow; Frantz Fanon’s Toulon. Chance encounters are his main fact-finding exercise. “I love having a chat in a cafe and thinking, ‘Why are we both here?’” he says. “To get this balance between everydayness and speaking to deep histories.”

In Berlin’s French Cathedral, Pitts spots and befriends a family from an Afro-gospel choir; in Moscow he gets chatting to a Nigerian man dressed as a tsar, who tries to sell him a Barack Obama matryoshka doll. Taking nearly seven years to complete, the book is not so much about the author reconciling his own Black identity; it’s more about a young person going into the world, looking for evidence for an enchanting idea – that exposure to composite cultures is a vehicle for self-knowledge, a worthwhile tool in the puzzle to understand contemporary life.

“There’s this whole subaltern visual world that the notion of Blackness can hold,” Pitts says. “It so often gets reduced to black-and-white images of people in trilbies in the 1970s. There’s an opportunity to make it weirder and surreal.” Events like the Windrush scandal may draw attention to the mistreatment of Black Britons by the state, but if they are the only lens through which Black culture is commemorated, little room is left for subcultural texture. Afropean relishes the characters behind the buzzwords. Years after the interviews were conducted, they remain refreshingly blunt. Saleh, a Tunisian bouncer Pitts meets in Stockholm, offers a scathing assessment of his adopted country. “Swedish people will always live good… but they have slaves, they need people like me to make sure only the right people get into their clubs,” he says. “People in Europe think they give immigrants a favour. But they don’t realise that we are only here because they destroy our countries.”

Pitts does not shy away from the anxieties that surfaced during his travels. Meeting an African American couple on a Black history tour in Paris, he writes that “I felt culturally flimsy, as though my identity was vague and half formed compared to my American friends’, my English accent lacking substance when talking about Black identity”. He attends to his prejudices too, recounting that when he had his phone stolen in Paris, he assumed that the pair of thieves were Roma – as the police had assured him. “I could only assume,” he concedes, an honest commentary on how stereotypes are absorbed.

In an age of diversity and inclusion, identity politics and decolonisation, Pitts’ approach is slightly out of fashion. He is interested in the strangeness produced by communities mixing, the messy edges rather than neatly packaged groups ready to be ‘championed’ by outside interests. “I want to take Blackness slightly outside of its comfort zone,” he explains. As a northerner, he opposes what he terms the “Brixtonisation of Black Britain” – “the reduction of the Black British experience into a single, neat, London-oriented narrative”. He was involved in The Guardian’s Cotton Capital series on Manchester’s historic slave links, but his own work is less anthropological and data-driven, leaning more on anecdote and affect. “[Cotton Capital] is important work, but sometimes it can be used to virtue signal,” Pitts reflects. “And I do wonder who it serves ultimately.”

Pitts’ studio is just a five-minute walk from South London Gallery, where the 2023 exhibition Lagos, Peckham, Repeat: Pilgrimage to the Lakes traced the connections between Nigeria and south-east London. From Autograph to shows like Museum of London’s Grime Stories, the cultural platforming of Black Britain is often centred on the capital. “When you grow up outside of London and Birmingham, your experience is different,” Pitts says. “I still don’t feel that connected to London.” Maybe his studio is a research base rather than a preferred environment; a space to reconnect with his archive before going into the field, where the real work takes place.

After the murder of George Floyd in 2020, Pitts felt “uncomfortable about this economy opening up around the death of this Black man”, whereby Black artists were suddenly asked to respond to the incident. But when poet Roger Robinson came to him with an idea for a project exploring Black Britain in the wake of the toppling of Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol, Pitts agreed to collaborate. The pair decided to focus on the coasts, weaving centuries of imperial history, deportations and immigration into Home is Not a Place, a project of photographs and poems. Pitts mentions Paul Graham’s A1: The Great North Road as an inspiration, “a singular route that speaks of something bigger”.

“It’s difficult to make work that is meaningful in an art world where in order to survive, everything has to get commodified”

Commissioned by the Ampersand/ Photoworks Fellowship, the work was first shown as an exhibition at Graves Gallery, Sheffield, before travelling to Edinburgh’s Stills Gallery, and then to The Photographers’ Gallery in London last year. It was also published as a book in 2022. Pitts’ photographs are presented without captions, a nameless tapestry. A child poses in front of a windy Stonehenge; a Tesco cashier stares into the distance. “It wasn’t ethnographic details of populations,” Pitts says. “It’s more a poetic rendition of these places, creating a metaphysical map inspired by conversations and local knowledge.”

Assorted portraits show police officers, festival-goers, mourners, and kissing couples – the breadth of human experience in disarming mundanity. Robinson narrates Black life from within while conveying the novelty of seaside encounters. “A Saint Lucian and a Nigerian are talking / about the quality of light, in art and writing,” one begins. “This sacred conversation between / sky and sea is a stillness and solitude,” goes a couplet written from Holkham Beach, north Norfolk.

Pitts fills in more of the book’s gaps. “There’s a mixed Ghanaian and Irish IRA member living in Belfast; Jamaicans from Brixton; men from Saint Kitts in Southend- on-Sea,” he says. Scottish model Eunice Olumide features, as does novelist Caryl Phillips, another important mentor. A living room installation in the exhibition echoes the rich cultural mix which defined Pitts’ youth; books by Gordon Parks, Roy DeCarava and Liz Johnson Artur stacked next to Tron and RoboCop VHS tapes.

“The idea was to find a home for the diaspora – a space of consolation for the Black community, rather than for the art or literary establishments,” Pitts says. He laughs when recalling a white man who stormed out of Graves Gallery, furious at the pirate radio hip-hop blaring into the space. “The people that you have to speak to if you want to make your way through the photo world generally don’t give a shit about the type of places and people that I represent,” Pitts says. “On the one hand I’m trying to transgress photo-world norms, but on the other, to conform to the types of places I grew up in.” He pauses, rising from his chair to make a herbal tea.

Tokyo drift

When Pitts’ father’s Motown-inspired band The Fantastic Temptations broke up, he retrained as an actor. A few years later, he was hired on the Japan leg of the Starlight Express tour. Aged five, “we got lifted from these terraces that were being decimated by Thatcher into five-star hotels in bubble-era Japan,” Pitts says. The experience changed his life, giving him a wider perspective denied to his Sheffield peers. Several friends from his childhood ended up in prison or dead. “Going to Japan gave me the confidence to pursue a career in creativity,” Pitts says. “I knew there was another world out there beyond my confines.”

Japan remains at the centre of Pitts’ enquiries into what he calls “glitching nostalgia and failed futures”. He thought that late-1980s Tokyo was the blueprint for developed societies; surely Sheffield would look like the Japanese capital in 20 years’ time. “I remember thinking, ‘The future’s going to be great!’” But on returning to Sheffield, he noticed a dichotomy which soured Japan’s apparent glamour. “The very thing that was destroying Sheffield – neoliberal capitalism – was helping Tokyo thrive,” he says. When Japan’s asset bubble burst in 1992, the illusion was shattered. Pitts’ home and adopted dreamland were now both stagnating.

Pitts became obsessed with “this future nostalgia that didn’t work out”; the UK never became like the boom-years Tokyo, instead entering periods of centralised financialisation and deep regional inequality. His childhood memories now exist in a strange state of both past and imagined future. “There were a lot of problems with Japan: it was all about greed and consumption, but it was fucking beautiful as well,” he says, visibly excited. “When something’s beautiful – even when it’s problematic – you’re always going to have to deal with that and be really honest about how humans deal with beauty.”

Politics is the realm of the head, beauty of the heart. Pitts’ work is about being honest with the forces that act upon us, aesthetics alongside material realities. There is no hypocrisy in pointing out how devastated the north of England feels while also being a staunch defender of Sheffield’s culture. There is a moment towards the end of Afropean when Pitts arrives in Gibraltar. “No matter how hard I tried to shake it: all this British bollocks still felt something like home,” he writes.

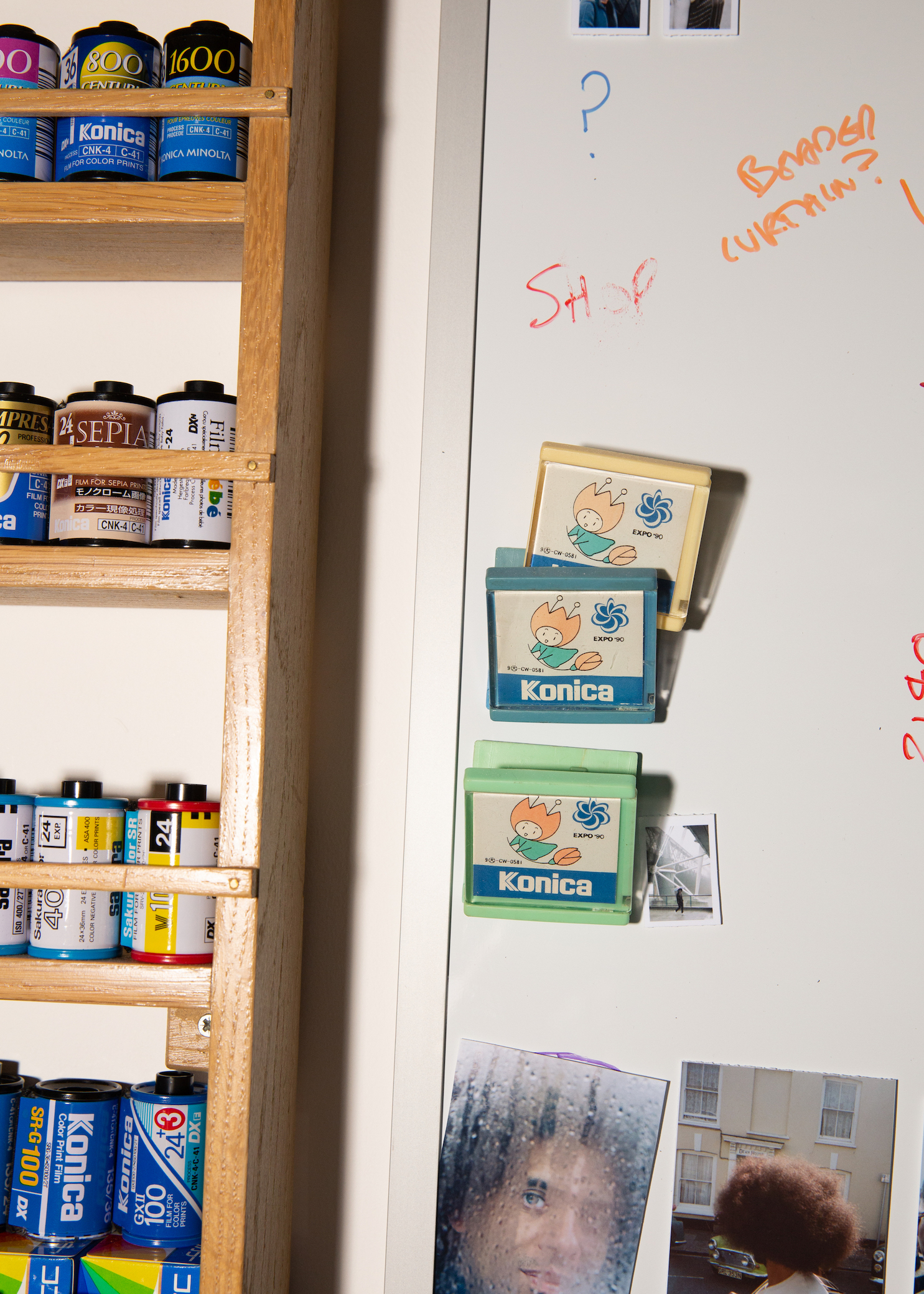

Pitts recently returned to Japan after 23 years, shooting Tokyo using his parents’ old cameras. He used the Konica film that now litters his studio, while his family’s cameras sit atop a Konica lightbox above the sink. During lockdown, Pitts stayed at his childhood home with his partner and two daughters, spending weeks sorting through old negatives. The Sequel to a Dream: Ghosts of 1980s Japan combines his new images with the family archive. The cameras have reverted to their original timestamps, Pitts says, “their era encoded in the present”. The creative process is bound up with mourning his father.

“There were a lot of problems with Japan: it was all about greed and consumption, but it was fucking beautiful as well”

He passes me a book maquette of the Japan project. The pictures are smoky, the neon street signage breaking gently through the haze. Pitts is taking his time, waiting for the right publisher to bring the project to life. More than any of his work about Black Britain, it relies on intuition and half-memories. He fills in the gaps with his own pictures, but the story’s lingering uncertainty is deliberate.

An electric diffuser continues to puff steam into the studio; the plastic flute of water Pitts gave me is now empty. Our conversation turns once more to the future. Pitts likes having his studio opposite Camberwell College of Arts, where he can see what the students are making (and wearing). Each generation risks misremembering the past, he says, heightening the need for diligent archiving. The economic and social upheavals of the past 50 years make the period particularly vulnerable to pernicious retellings – glorifying the booms without learning from the busts. “I feel that it’s my generation’s responsibility to re-examine and remember the 20th century,” he says. “To think about some of the good things, but also to challenge some of the nostalgia.”

Perhaps time, rather than place, is Pitts’ main subject. He recently released a BBC Radio 4 series called The Failure of the Future. He does not want to be pigeonholed as an artist solely of Black life, an expectation that Black photographers have had to contend with for generations. He recalls a conversation with Ming Smith about the difficulty of garnering interest in her late-1980s Japanese work, and also mentions Mohamed Bourouissa, who told Pitts he wants to make work about artificial intelligence rather than be known solely as a social documentarian of the French banlieues.

“Why shouldn’t we be allowed to also do other things?” Pitts asks. “It’s difficult to make work that is meaningful in an art world where in order to survive, everything has to get commodified.” His tone is one of lament, but it is short-lived whenever it surfaces. A few days after we speak, I see pictures on Instagram of Pitts giving a walk-through tour to the patrons of The Photographers’ Gallery – I wonder what’s running through his mind as he opens his life to the art establishment. A wooden table in the gallery has the rainbow Konica logo coloured into its surface, the same design that, after a few hours in his studio, seems to blend into its background. There is a sign resting on the deskside cabinet that says ‘Slow Down’. All Pitts seems to be asking is for people to pause and think differently, or more simply, perhaps, to think.

After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989-2024, curated by Johny Pitts, is at the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, 29 March-16 June; Focal Point Gallery, Southend-on-Sea, 3 July-14 September; and Bonington Gallery, Nottingham, 27 September-15 December