All images © Émile-Samory Fofana

Émile-Samory Fofana’s Champions League Koulikoro traces the influence of European clubs on African fans – and their own aspirations beyond the pitch

In 2018, French-Malian photographer Émile-Samory Fofana could be found on a roof in Bamako, camera in hand. It wasn’t that he was expecting anything particularly exciting to happen; he was just observing what was going on the street below. Even on the roof, the short architecture of the city ensures that, in Fofana’s own words, “you can still have proximity, you know who is in front of your house, you hear every word.”

Fofana’s vantage point threw the commonplace into unexpected focus. “There were collectors jerseys, bootlegs, collaborations like Manchester City-Louis Vuitton or PSG-Chanel that never really existed,” he says. “I wanted to make an archive of all the shirts I saw passing by – it was a street photo project but, ultimately, what interested me was collecting and creating a directory.”

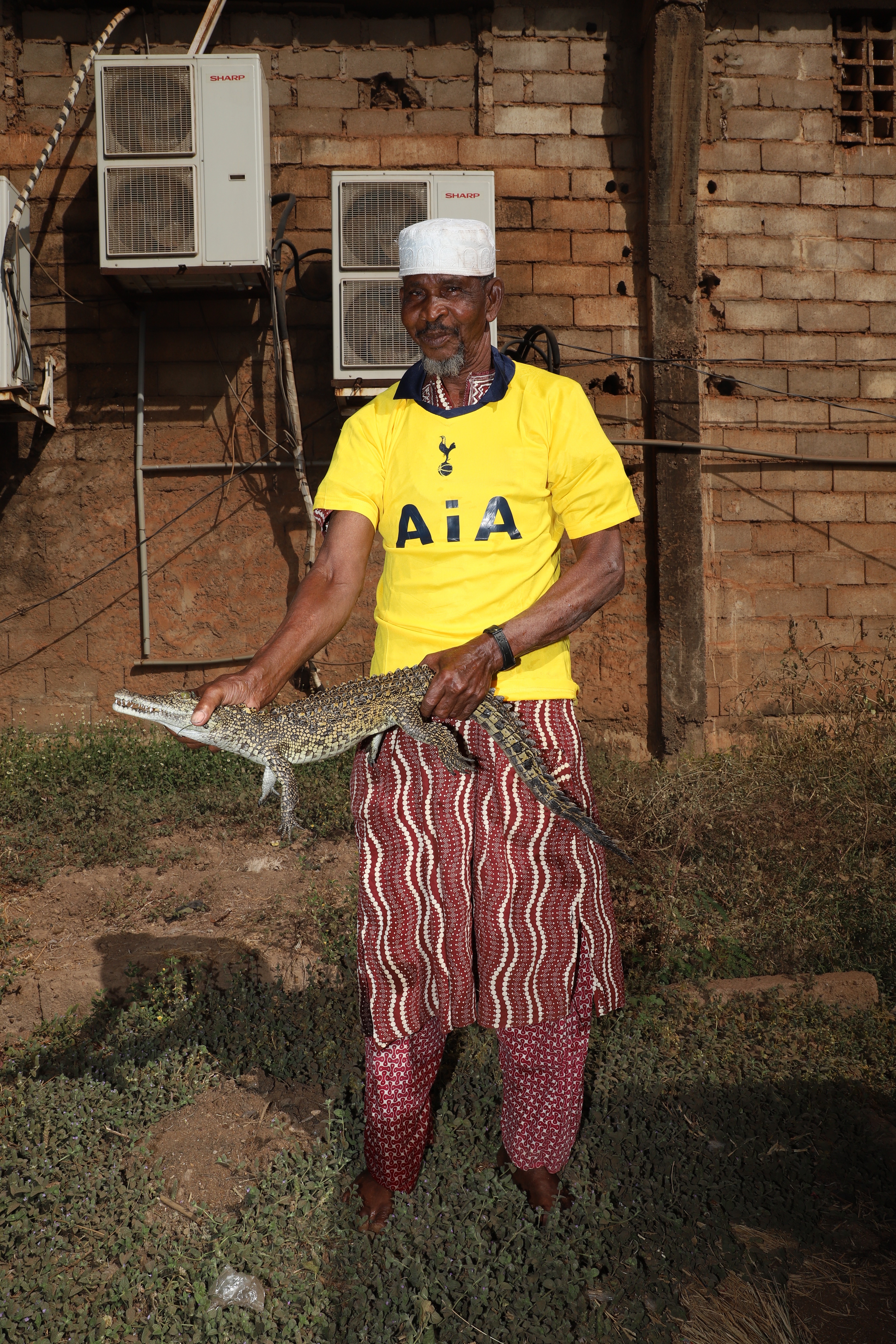

In the five years since, Champions League Koulikoro has become a repository of images of the fan-champions of football in West Africa. Fofana has ventured away from the roof and into the streets, markets, and homes, focusing on different groups in society. “I’d spend days with workers from fishermen to mechanics or blacksmiths, to document how football shirts are worn as workwear, then focus on women or people in conflict zones or those going to the mosque,” Fofana explains. The initial concentration on football shirts became a gateway for a broader documentation of contemporary West Africa that has since been exhibited across the world, from Miami Art Week to London’s OOF Gallery – and at the African Biennale of Photography in Bamako where the work began.

The fervour for football in this part of the world runs deep – so deep that the myriad of shirts proclaiming an affinity with foreign teams is completely unremarkable. “People do not know much about West Africa in Europe, but they are among the greatest supporters for these European teams that I have seen in my entire life,” Fofana says. “The biggest fans of Real or Barca – they’re in Casablanca, they are in Bamako, they are in Dakar.” Once Fofana noticed the trend, documentation was the first priority. “It was interesting to reverse the gaze, because Africa looks a lot at Europe in terms of football,” he says. “Football gives concrete expression to all the aspirations of young people; there is always this desire to go to Europe, to play in Europe, to change your life.”

Fofana’s work builds on a long tradition of Malian street and portrait photography, known internationally through the work of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé. He cites Tobias Zielony’s portraits of overlooked youth as his main influence. Fofana’s work confounds the idea of gaze by turning attention back on those who so closely watch European teams (gazing, if you will) without the power or authority that the term has come to imply. This contrast between the European league – with all its associated fame and wealth – and its West African supporters is at the centre of Champions League Koulikoro.

The breadth of environments forced Fofana to adapt his working processes, impacting his style. Shooting in public spaces, often on the back of a motorbike driven by his cousin or in areas of heightened conflict, meant working quickly and using a more discreet camera or a phone. His subjects, whether market sellers or children, rarely engage with the camera. Some have their backs turned while others appear to just turned away, letting the focus fall on the shirts, crests and player surnames emblazoned across them.

“Football gives concrete expression to all the aspirations of young people; there is always this desire to go to Europe, to play in Europe, to change your life”

“In Africa, football is in the public space all the time,” he says. “People put their TVs outside to watch the games, creating what I call micro stadiums, and trash talk between neighbours and this social element is very important.” Football takes on another life that many beyond the continent have rarely paid attention to. Although fans globally are beginning to take notice of the African Cup of Nations, Fofana’s images tell outsiders that there is more to African football culture than the biannual tournament.

But it is the staged images shot away from the public sphere where Fofana truly foregrounds the fans. In one image, a young man stands in a yard while his two young nieces cling to his arms, proudly presenting a PSG shirt to the camera – echoing portraits announcing new signings at major clubs. The images often exhibit a playfulness, implying a reciprocal process between photographer and subject; the interest has moved beyond the shirt. Combining staged and unstaged imagery allows Fofana to show the impact of football across society, documenting the spectrum of fans while moving beyond the shirt and towards the individual.

There have always been star players, but in recent years it has been possible to talk of a whole new generation of African players in Europe. When Champions League Koulikoro began, Messi and Ronaldo shirts dominated, but homegrown players were also gaining prominence (particularly Senegal’s Mané and Egypt’s Salah when they were playing together at Liverpool.) Through football, Europe is familiar. Fans will often know the major cities, or even the geography of Spain or England, owing to the strength of their teams. Few in Europe share that level of knowledge about Africa. Champions League Koulikoro is “to show that European football exists and is being experienced not only in Europe, but also in Africa,” Fofana says. “It’s like ‘Hey, look at us, look at Africa too, look at what’s going on.’”