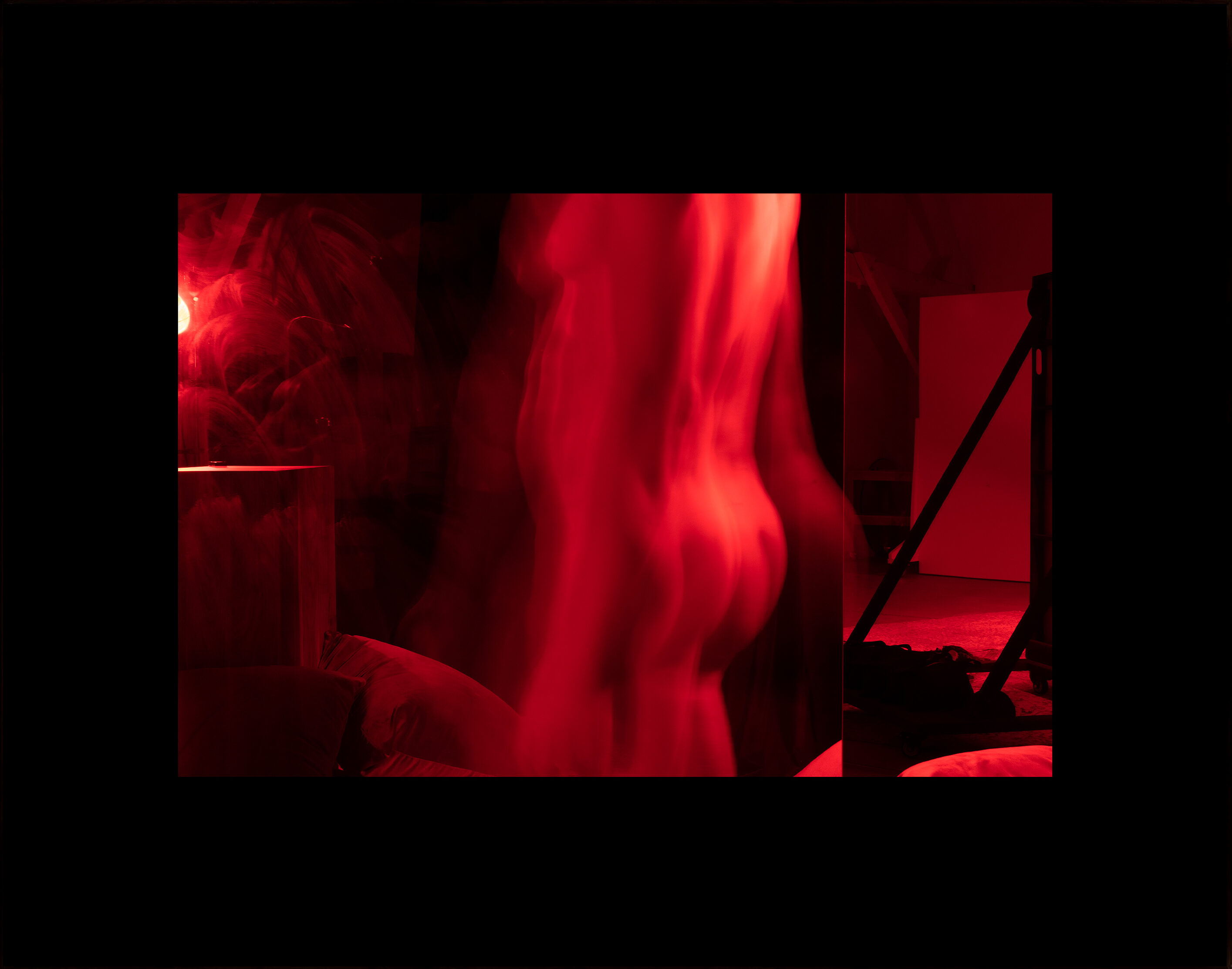

Dark Room Model Study (0X5A1728), 2021. All images courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich, Paris

A pioneer of the early-2000s queer zine movement in New York, Paul Mpagi Sepuya brings his portrait evolution to the Midlands

No photograph, project, or exhibition exists in a vacuum for Paul Mpagi Sepuya. Instead he works in a continuous flow, each image an accumulation of motifs and techniques built over 25 years – though he is not always initially conscious of how. “It’s only in retrospect that one project ends and another begins,” he says. His solo shows are “the moments where it becomes opportune to formalise ideas, make meaning and test things out”.

That makes Exposure, Sepuya’s exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary, an experiment of sorts. An experiment in collaboration with curator Nicole Yip, who devised the show’s concept of the ‘double exposure’ – an idea playing both on the technical process of image-making and ‘exposure’ of the work to the public. And an experiment in transmission: to see how Sepuya’s references – to the East Coast queer scene, 19th-century daylight studios, the writings of Harlem Renaissance artist Richard Bruce Nugent – conspire and communicate in a distant environment.

“My work has shifted from thinking about portraiture as a definitive thing, and more rather like portraiture as an ongoing, underlying source for the work”

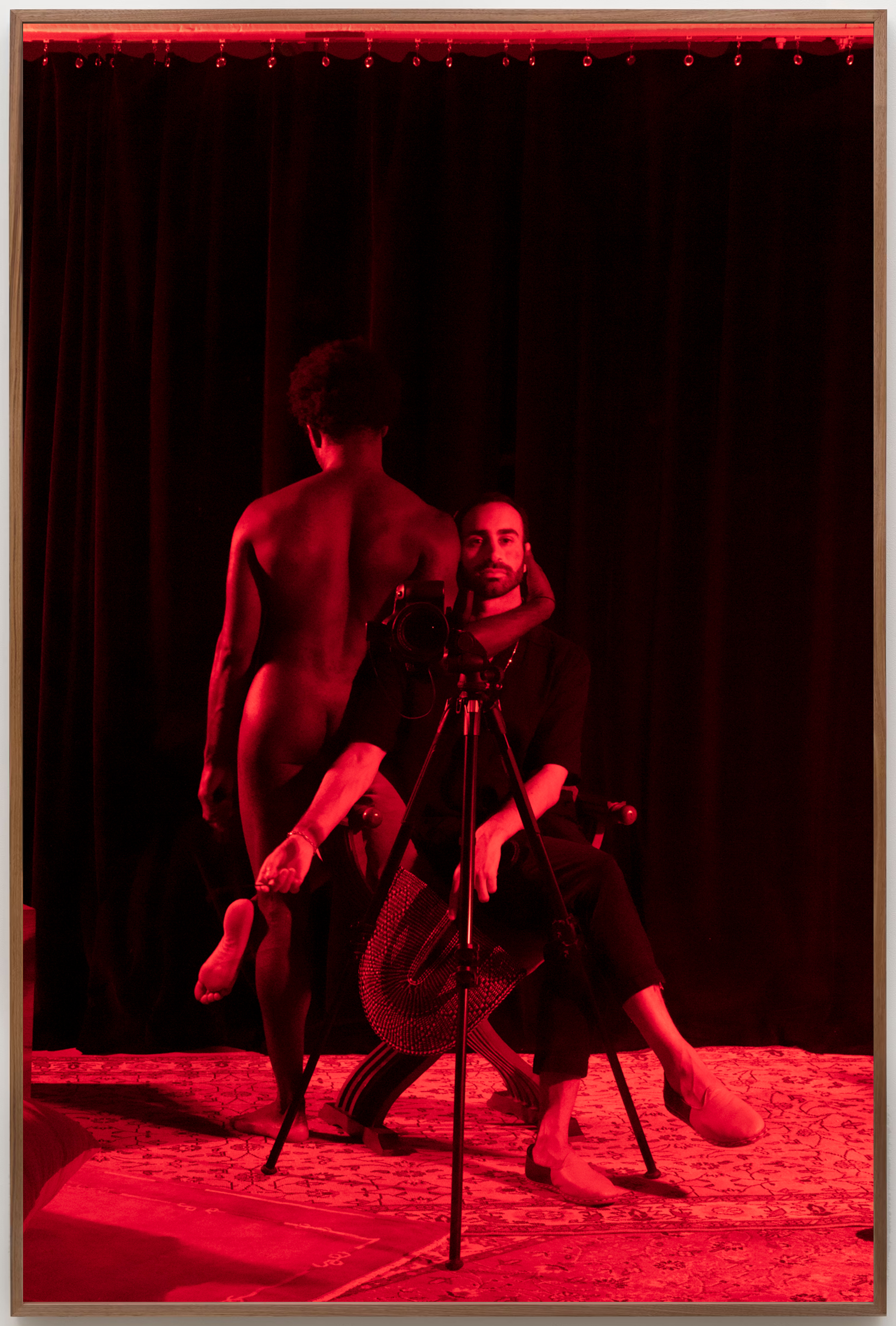

Exposure presents 40 works mainly from Daylight Studio / Dark Room Studio, in which Sepuya uses red lights, props and mirrors to question the dynamics of studio portraiture. Begun in 2017, the series stretches beyond the traditional boundaries of the photoshoot, disrupting the hierarchy which places final image over process, setup, and the relation between artist and sitter. The show represents an evolution from casual domestic portraiture to something more self-referential, but without losing the intimacy of Sepuya’s early shoots. “My work has shifted from thinking about portraiture as a definitive thing, and more rather like portraiture as an ongoing, underlying source for the work,” he tells me. “It’s about the complications that are produced in the making of portraiture.”

Sepuya’s practice began at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts where he studied for a BFA in photography and imaging until 2004. The early 2000s was a raw time in New York shaken by the September 11 attacks. Artists were at the forefront of the queer and cultural revivals. Sepuya mentions Will Lovelace and Dylan Southern’s 2022 documentary Meet Me in the Bathroom as “very much the place I was in New York” – a daring Williamsburg counterculture where people partied and marched together against the US’s wars in the Middle East.

With ambitions to become a fashion photographer, Sepuya began shooting friends in his apartment, capturing the intimacy of his social circle. Looking back, the pictures appear as domestic portraits, but not necessarily “the way a subject is revealed through not only figure but also an eye into their surroundings,” he explains. After all, the subjects were in his home rather than their own, allowing him to break the association between person and prop and instead strip the setting, gesturing towards studio arrangements. “It took a while for me to realise what I had taken for granted – that I was photographing in my home, a place where I was already very comfortable,” Sepuya says. He would use blank walls and show just the edge of a table or bed, anticipating the manipulation and obscuring of surfaces in later work.

The queer scene gathered momentum and Sepuya’s portraits found a home in BUTT magazine and his own SHOOT zine, in which he published a single male portrait session each session, often featuring nudes. “These portraits that I was just making for myself started to circulate in a way that I hadn’t anticipated through social media – they became quite notorious,” he explains. “I was thinking about the way in which portraiture is wrapped up in this economy of exchange and solicitation – particularly by gay men in homoerotic spaces.” AA Bronson founded NY Art Book Fair in 2006, giving the scene new exposure and expanding Sepuya’s list of friends and subjects. The period triggered a new way of interpreting visual culture. “How do images work in the world?” Sepuya wonders. “How do they circulate and transform relationships? How do they come back?”

If New York inspired the male poses and careful bodily observation in Daylight Studio / Dark Room Studio, its treatment of studio spaces has nomadic origins. As more friends began making portraiture around 2010, Sepuya would turn the lens on their shoots and his own, creating a literal introspection. He mentions a Cecil Beaton photograph of Pavel Tchelitchew painting his muse Peter Watson with poet Charles Henri Ford also present – a conscious layering of friendship and artistry within the frame. Sepuya became interested in “recognition and the way that photography is positioned,” he explains. “The camera as a vector pointing outwards and allowing you to understand the position of the artist, the author, the photographer through those things that surround them.”

Residencies at the Center for Photography at Woodstock, The Studio Museum, Harlem, and on Fire Island allowed Sepuya to gather props and explore rephotographing using images from correspondence with friends. He learned how to shoot on digital during his MFA at UCLA and began incorporating mirrors in his compositions. This enabled him to integrate images made while travelling in Europe and Mexico, fixing prints to mirrors and puncturing the presumed boundaries of the studio.

In Exposures, images feature mirrors littered with research material – “a studio space that could be both the recurring background for an image but also would slightly change over time,” Sepuya explains. Gold fabrics were important for referencing Modernism and Surrealism, while Black velvet maintained the sexual gestures of mid-20th century homoerotic photography while also nodding to 19th-century large-format dark cloths. The combination of black fabric and mirrors “opened up new ways of thinking about the idea of Blackness in terms of material – and the necessity of Blackness for making latency visible,” he says.

Sepuya has exhibited extensively over the past seven years, a form of stress testing for images in constant dialogue with their predecessors. A small show at Team Bungalow, LA, in 2017 was a debut for his darkroom images, which then went to Document in Chicago the following year. Inclusion in MoMA’s Being: New Photography 2018, the 2019 Whitney Biennial and the Barbican Centre’s Masculinities: Liberation through Photography (2020) confirmed his position in the new curatorial focus on queer reflexivity. Recent forerunners for Exposure were shows at Bortolami Gallery, NY; Vielmetter, LA; Deichtorhallen, Hamburg; and last year’s twin Peter Kilchmann display in Zurich and Paris. “Where the ideas come in is always responding to observing what happens once the work is made,” Sepuya explains. So viewers in Nottingham will engage in many kinds of spectatorship: with the artist, his subjects, the studios – and previous audience perceptions.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Exposure, is at Nottingham Contemporary until 05 May