Martin In my Room Elsynge Road Wandsworth, London, 1977. All images © Brian Griffin. Courtesy of MMX Gallery

Martin Parr, Anne Braybon and François Hébel commemorate a photographer who moved seamlessly between portraiture, art direction, documentary and advertising in a peerless career

“He had an incredible visual imagination,” says James Hyman, collector and founder of The Centre for British Photography, recalling the beguiling genius of Brian Griffin. “He saw things that were very prosaic and recognised some magic in them. He was true to the original spirit of Surrealism, creating a heightened reality.”

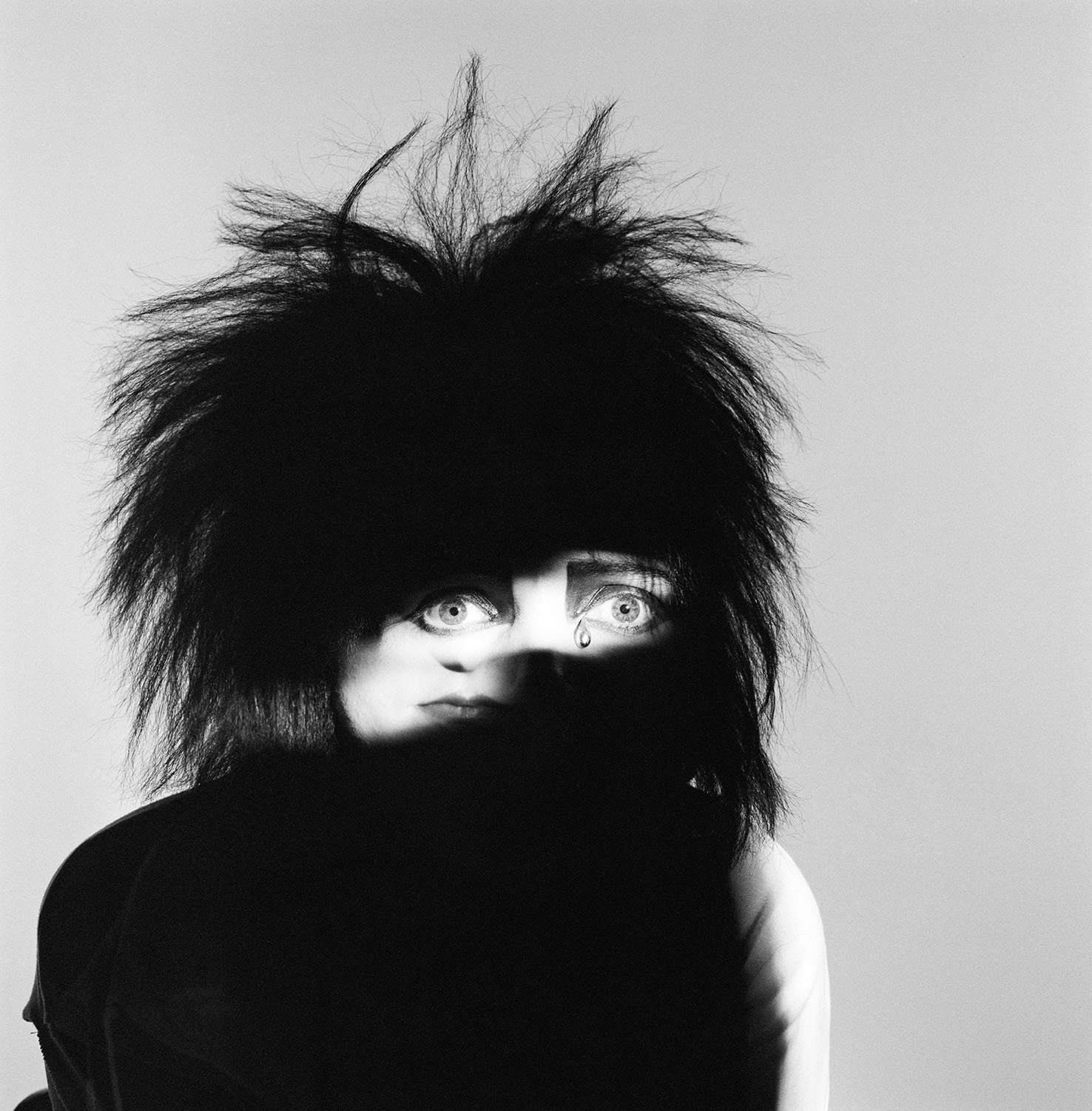

Griffin, who has died aged 75, will be remembered as one of the great portrait photographers of his generation. And though he is most closely associated with the extraordinary images he created in the 1970s and 80s for musicians such as Echo & the Bunnymen, Elvis Costello and Siouxsie Sioux – shooting some of the most iconic album covers of all time, including Depeche Mode’s first five records – the scope of his work extends far beyond music photography.

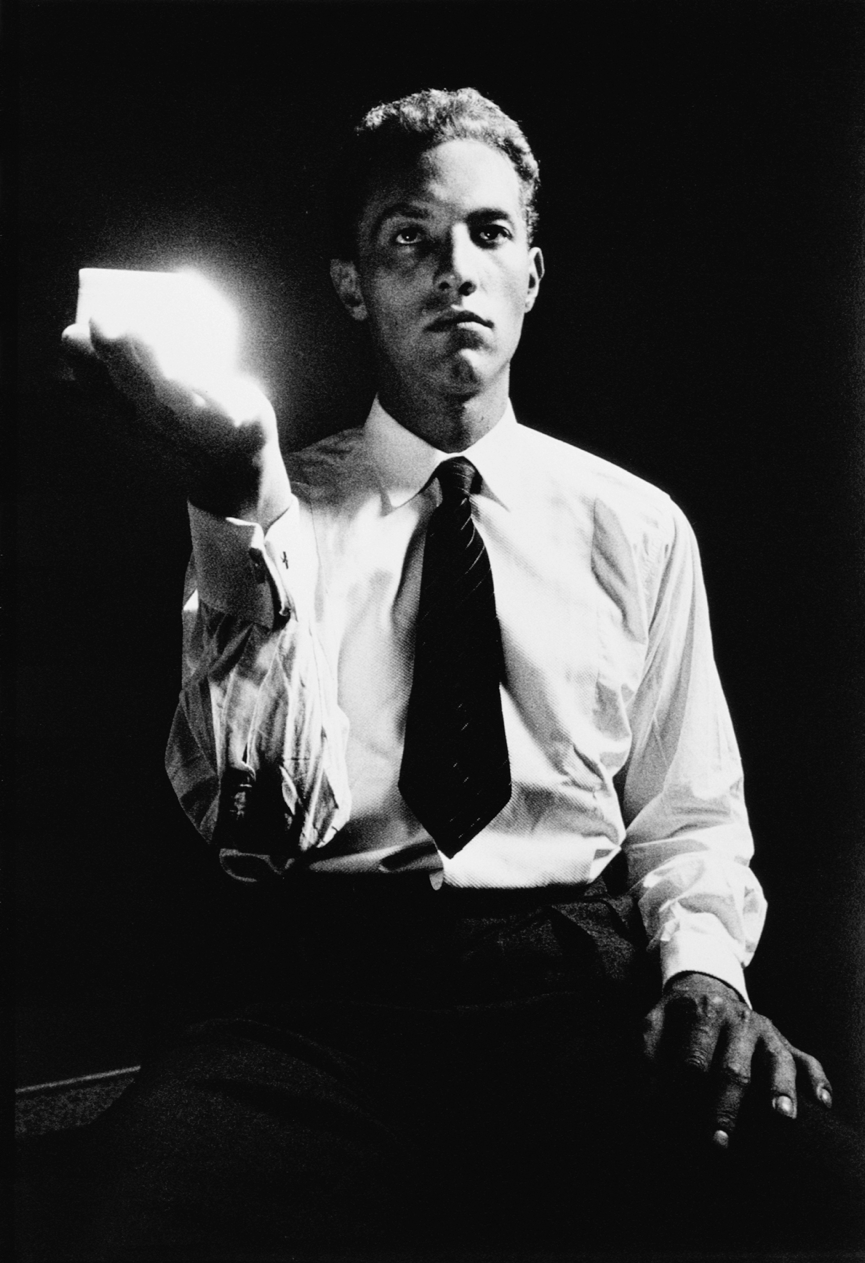

In his early career, Griffin introduced a bold new visual language to corporate photography, going on to create truly audacious campaigns that went well beyond any normal brief. Meanwhile, his work was exhibited in galleries, museums and festivals, starting with some key shows in Britain in the 1970s that were milestones in the acceptance of photography into the mainstream art world.

The 1980s were his peak years, when he produced some of his most famous images and he came to wider international attention. (The Guardian named him “the photographer of the decade” in 1989). In 2003 he returned to image-making after a 12-year segue into music videos and TV commercials. The photography landscape had changed, and there weren’t the riches of before, but there were garlands.

“He had a completely unique vision,” says Martin Parr, who met Griffin at Manchester Polytechnic in the early 1970s, establishing a lifelong friendship. “The kind of portraits he did, no one had seen anything like them before. He was a real innovator.”

Life in light

Born in Birmingham in 1948, Griffin had grown up in Lye in the Black Country, leaving school at 16 to work as a trainee pipework engineering estimator for British Steel. He remained there for four years, later saying that the clash and flash of nearby metalworks was a major influence on his imagery (the symbol of the heroic worker would figure throughout his 50-year career). At Manchester, Parr recalls that the pair “immediately connected and became friends.” Alongside Daniel Meadows and others, they formed a kind of salon, challenging each other in photographic games and studying the work of a new wave of self-styled documentary photographers such as Tony Ray-Jones.

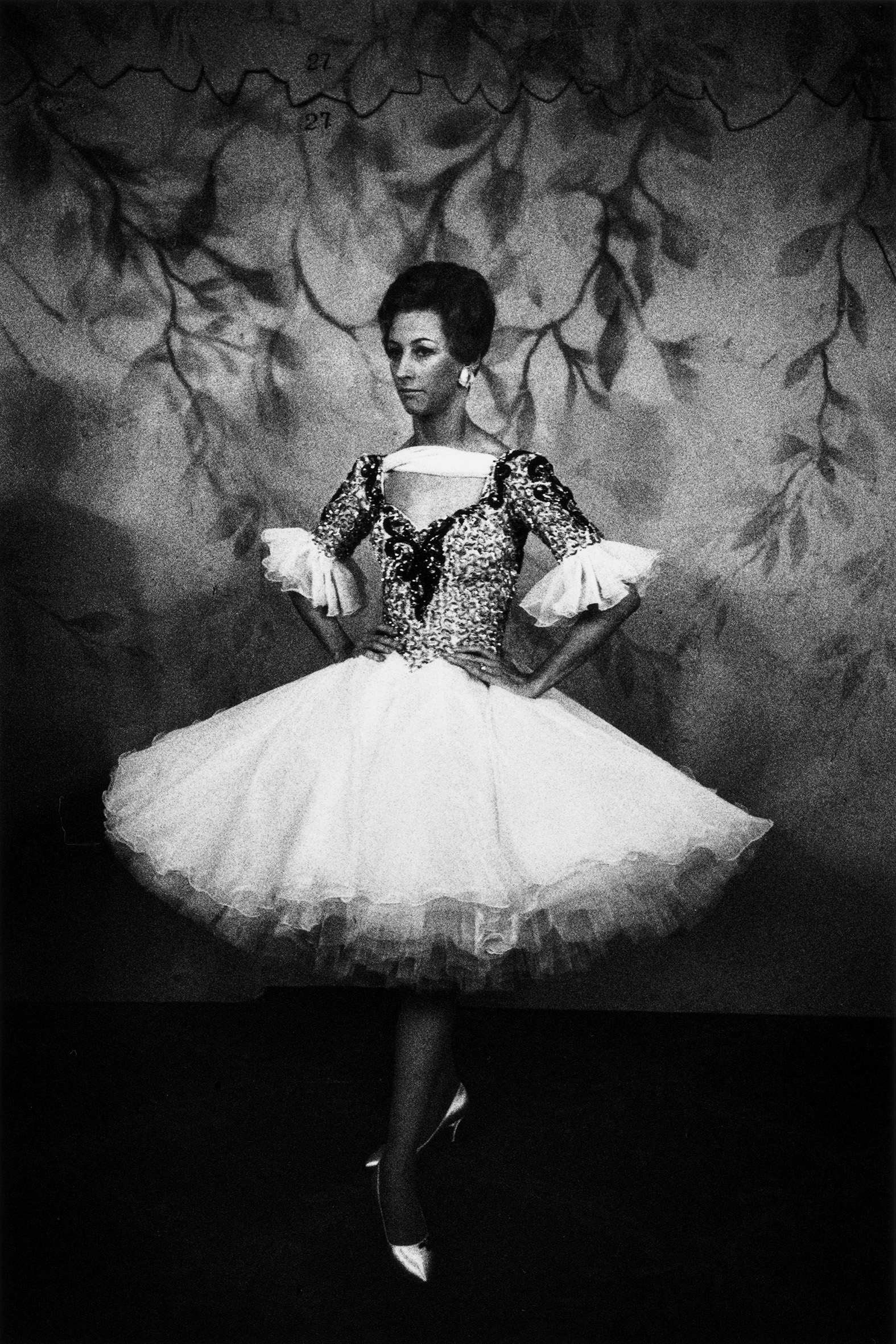

Griffin moved to London to pursue a freelance career, and taking a portfolio of black-and-white photographs of ballroom dancers to Roland Schenk, the celebrated creative director of Management Today, proved crucial. “It was an important meeting,” says Anne Braybon, who years later was art director of the magazine, and later still would commission Griffin for the National Portrait Gallery. “Schenk was the first to commission Brian, seeing in his work a new Robert Frank. He also introduced Brian to fine art and film, and those influences continued.”

Griffin repaid Schenk’s faith with extraordinary, theatrical, subversive portraits of otherwise nondescript business leaders. This bold approach formed the basis for an multi-award-winning and lucrative career that flourished in the boom years of the 1980s, working for design and advertising agencies while shooting cutting edge imagery for the music industry.

He was a virtuoso when it came to lighting, but the basis of Griffin’s imagery was observation, finding some small detail in his subjects to magnify and playfully twist. Perhaps his most famous album cover, Joe Jackson’s Look Sharp! (1979), was one of his quickest to shoot, capturing the singer’s bright white winklepickers in a shaft of sunlight while trying to find a location to make a portrait on London’s Southbank.

“He took chances, he pushed the envelope,” says Paul Hill, a leading figure in British photography by the 1970s who selected Griffin’s work (alongside Parr and Thomas Joshua Cooper) for Three Perspectives on Photography at London’s Hayward Gallery in 1979. It proved one the most important UK institutional shows of the decade at a time when the mainstream art world began waking up to photography.

“As well as having a great eye and an extraordinary sense of things coming together within a single frame, he used lighting in a very original way,” Hill explains. “Brian’s mission was to make unique images. Whether he was photographing Depeche Mode or Margaret Thatcher, he wasn’t trying to make a likeness or do a PR job. He was trying to make an important, unique photograph.”

Another key exhibition was at the 1987 Rencontres d’Arles photo festival. The festival’s director, François Hébel, had shown Parr’s The Last Resort the year previously, and Griffin’s former college mate suggested his work for the next edition, where it was exhibited alongside Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. The festival opened new opportunities for Griffin to exhibit across Europe, and he worked with Hébel again many times over the years in different guises.

“He was one of my closest friends in photography,” says the Frenchman. “I really admire his work, and I don’t think he gets the recognition he deserves. He had a way to get his subjects to do anything he wanted. There are very few photographers that have this ability to create signature images in the very short time [you have to shoot a portrait]. You instantly recognise a Brian Griffin picture. There is a consistency, even though he changed over the years, moving from black-and-white film to colour digital.

“I have seen him shooting, and he had such concentration in front of the people he was taking pictures of. I think that’s why they would always do what he wanted them to do; here was this guy in front of them with his eyes so intense.”

London calling

Griffin was also a pioneer in the field of photobooks. Parr reckons he was the first photographer in the UK to go the self-publishing route as an act of creative independence, collaborating with his great friend and “soul brother”, the acclaimed graphic designer, Barney Bubbles. There would be many more books throughout his career, and one of them, Work, marked a highpoint and in some senses a closure to the first half of his career. It was published in 1988 alongside a one-man show at the National Portrait Gallery, and went on to be awarded the best photography book at the Barcelona Primavera Fotografica in 1991.

Much of it was drawn from his best known corporate commission to photograph the new Broadgate development in the City of London. Typical of Griffin, he chose to elevate not the new buildings or the financiers, but the workers who built it. “Rosehaugh Stanhope, the developers, were erecting sculptures around Broadgate but none of them paid heed to the workers building the project,” Griffin wrote in his 2021 self-published biography, Black Country Dada. “So, Peter [Davenport, the designer who commissioned him] and I decided to create our own sculpture. However, this was a living sculpture using one of the project workers, Eric Foster, a steel erector.”

Griffin spent the 1990s shooting music videos and TV commercials, co-founding his own production company. In 2003, he was invited to support Birmingham’s bid to become the European Capital City of Culture. His return to photography after 12 years away sparked newfound interest in his back catalogue. Art Museum Reykjavik staged a retrospective in 2005, followed by large-scale exhibitions focusing on various aspects of his practice in Arles, Birmingham and Bologna, along with dozens of smaller shows. Griffin became a patron of Derby’s Format Photography Festival in 2009 – the same year he was honoured with a major retrospective in Arles – and four years later received the Centenary Medal from the Royal Photographic Society and an Honorary Doctorate from Birmingham City University.

A ‘rare’ generosity

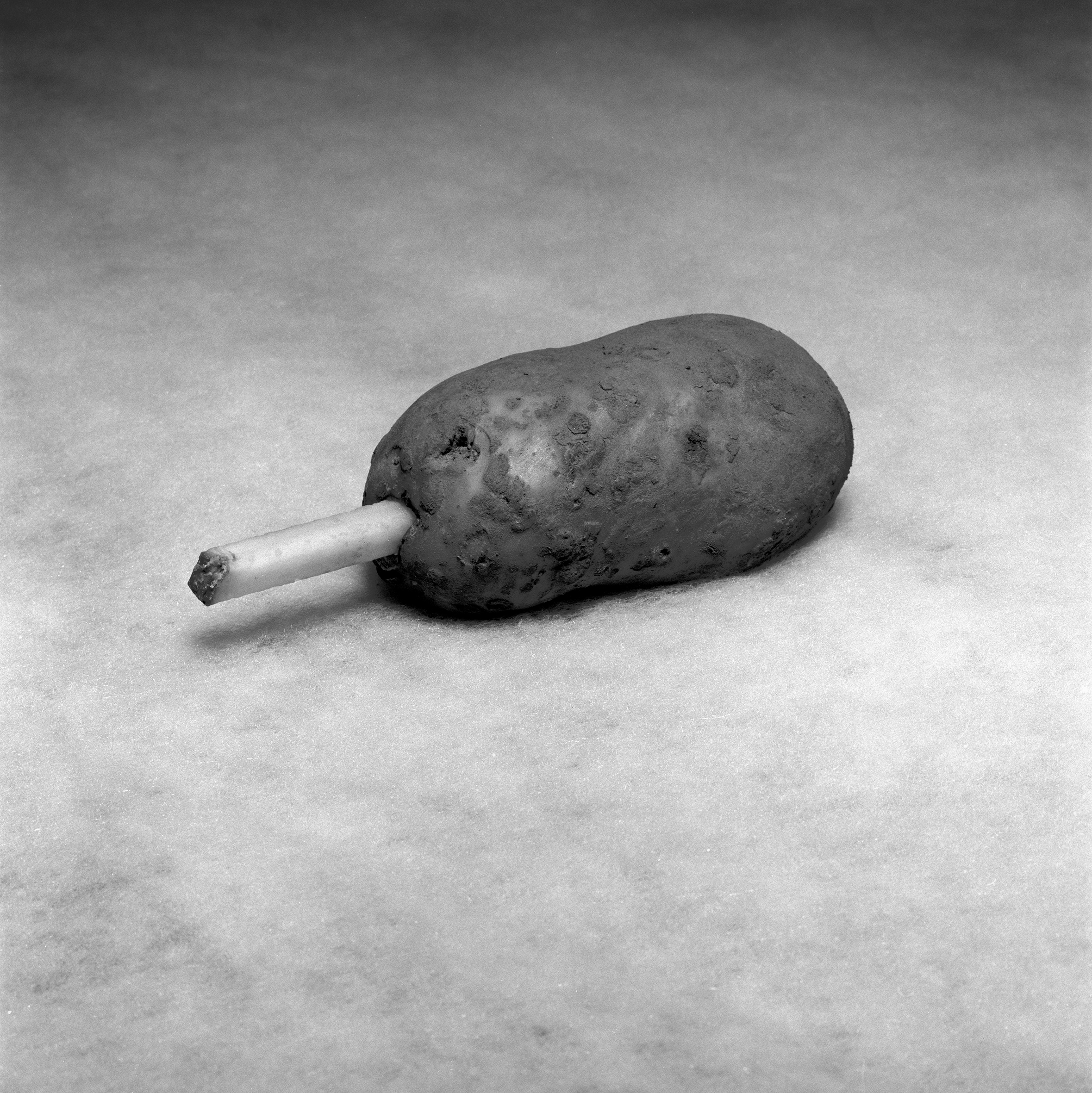

Yet his hunger to make unique images never diminished, and he remained prolific as both a photographer-for-hire and an artist in his own right. His personal projects were more tightly conceptualised and yet more varied in their focus, ranging from Gary, a series on his neighbours in Rotherhithe, where he lived and worked for more than 40 years; The Black Kingdom, based on his early years in the 1950s and 60s; and Spud, inspired by a residency in Béthune-Bruay in Northern France, marking the centenary of the end of World War I.

There were more major commissions too – notably for Reykjavik Energy, another for HSI and the opening of St Pancras station, and best of all, to his mind, for London’s Olympic Games Road to 2012, which he was determined to shoot, and was commissioned by Braybon for the National Portrait Gallery. “He was bold. He always went his own way,” s he recalls. “At the opening, Nadav Kander walked in to see Brian’s work, naming him ‘the master.’”

Hyman, who had planned to work with Griffin on a new retrospective this year, is certain of his importance in the story of British photography. “He’s got a central place in that history. He was also a very individual voice.” Like everyone else contacted for this article, Hyman mentions Griffin’s vivacity and generosity of spirit. Magdalena Shackleton, who supported Griffin’s work for years and showed two solo exhibitions at her MMX Gallery in South London, fondly remembers exhibiting his work at art fairs – and Griffin surrounded by friends in their local pub. “He always met people on the same level, whoever they were, and wherever they fitted into the business world or the art world,” says Hébel. “He would pull out a little something of his subjects so you would understand their role. But there was no hierarchy. And that is incredibly rare.”