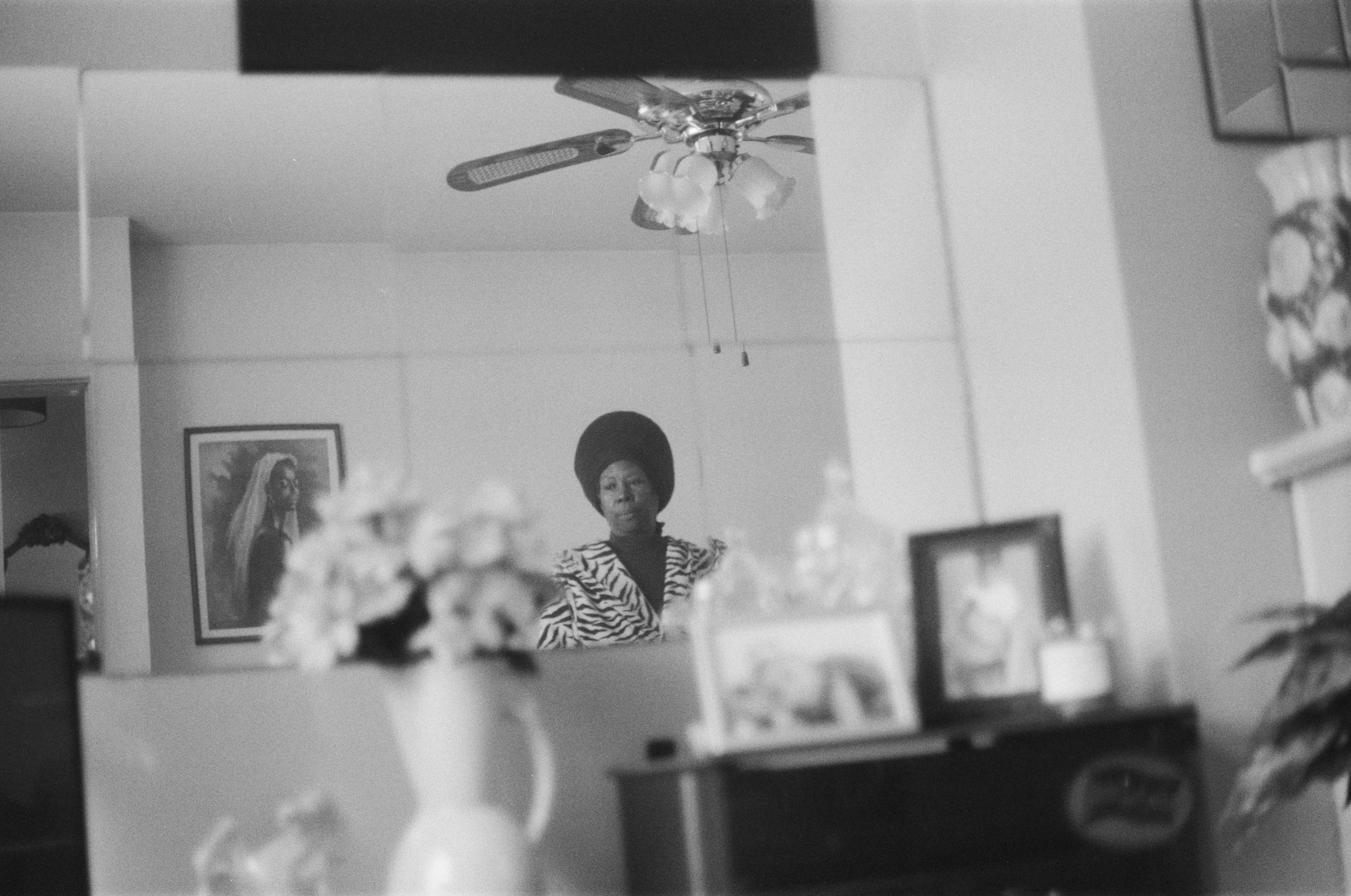

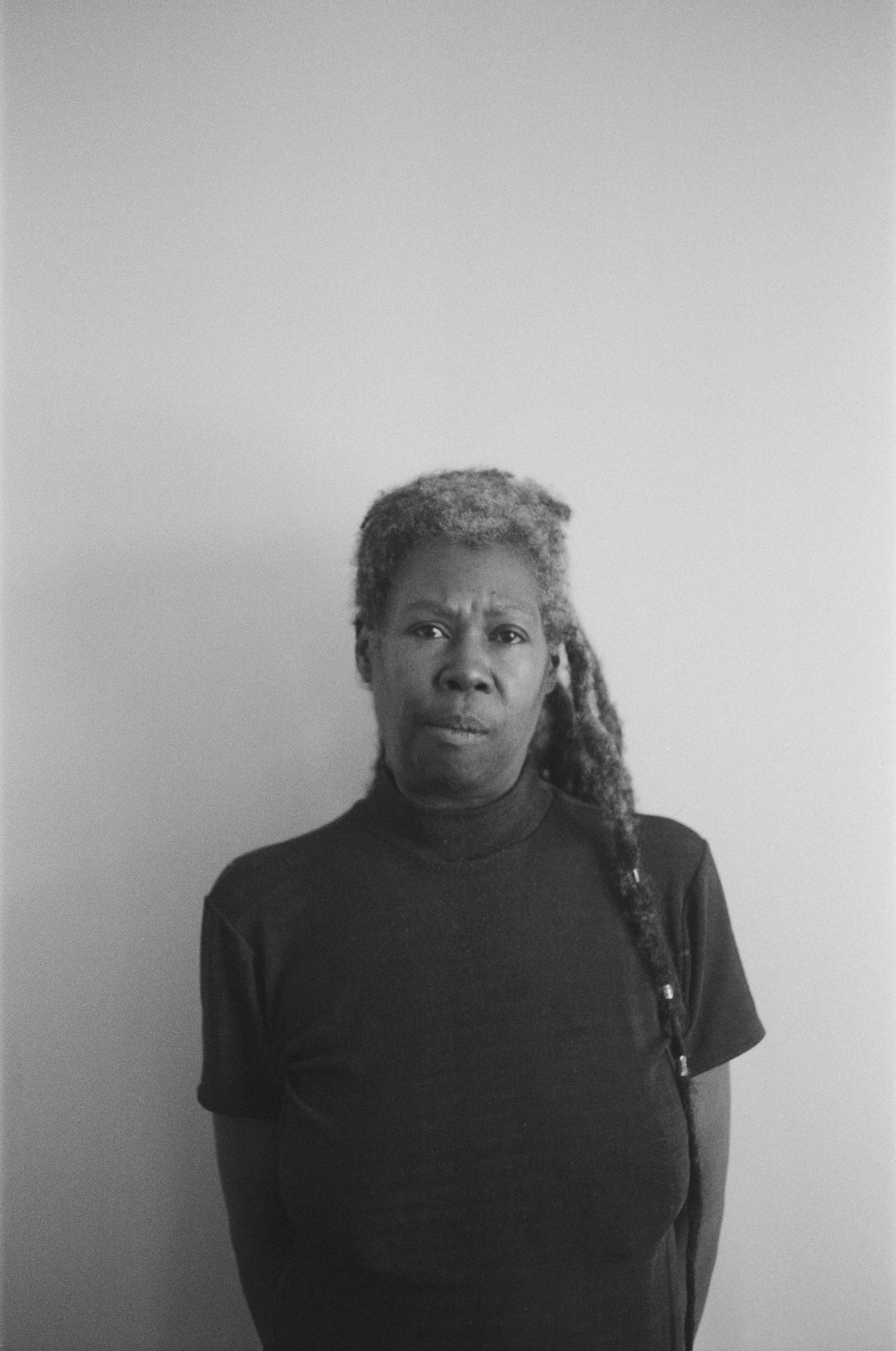

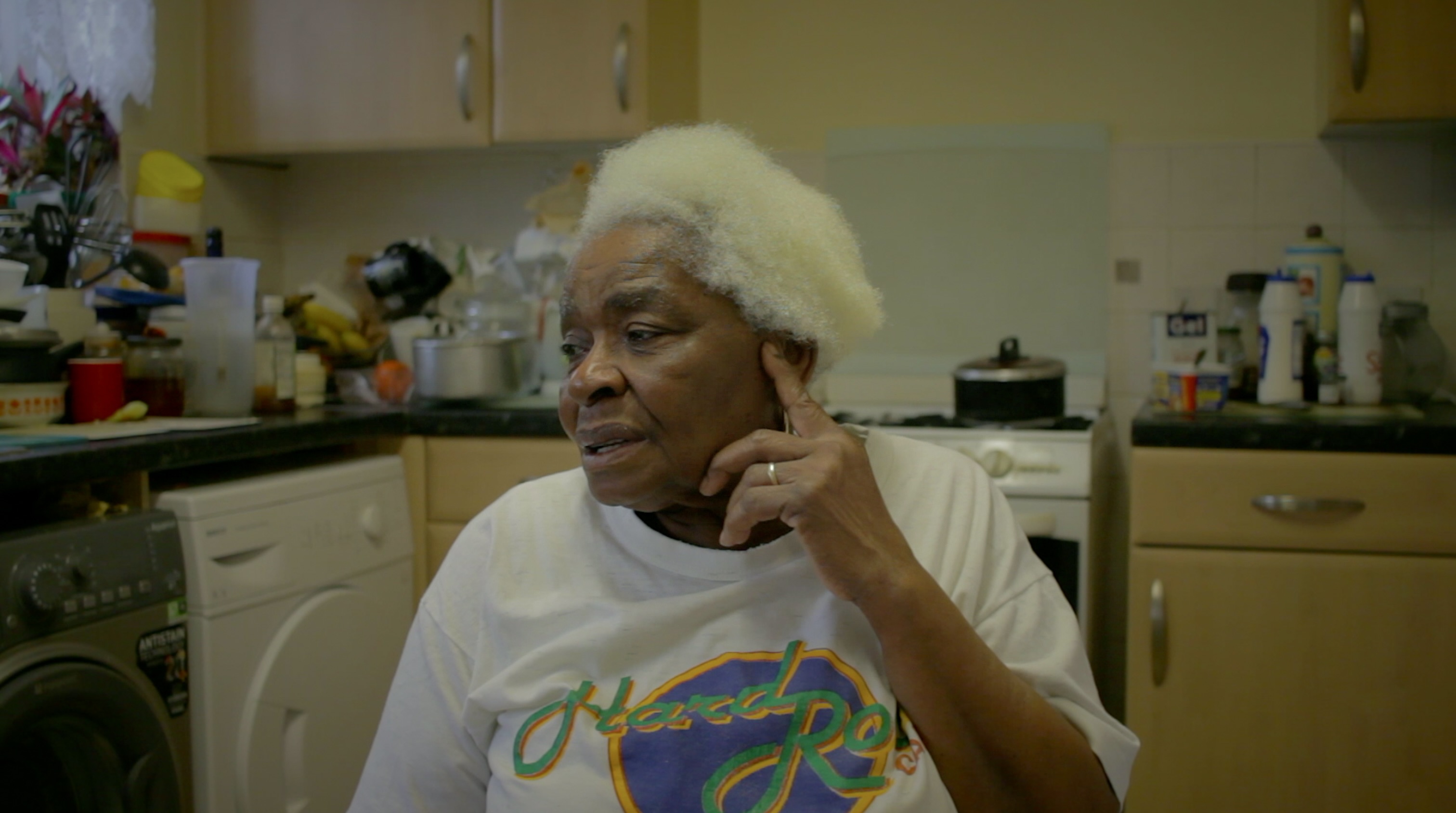

Access Subject 0122, 2022. All images © Marley Starskey Butler

Informed by their day job as a social worker, Marley Starskey Butler traces a complex upbringing via moving-image, text and photographs

Cramming the stack of papers into their rucksack and cycling home from the Post Office in May 2017, Marley Starskey Butler remembers feeling like they were carrying their “whole life” on their back. The decades-old children’s services records pertained to the first three years of Starskey Butler’s life with their birth mother, a period which had previously been a mystery to the Leeds-born artist. But some details remain unknown: many of the documents Starskey Butler received were fully redacted by anonymous officers who had decided the information contained belonged to someone else.

These personal records appear framed in Thirty-Six, an exhibition of Starskey Butler’s work currently on display at Birmingham’s Midlands Arts Centre (MAC). Weaving together projects made since 2009, the show draws on the artist’s childhood encounters with the social care system alongside later professional experiences as a social worker themself. Thirty-Six is “so personal that it becomes universal,” Starskey Butler says, opening up a space of reflection for visitors to step into and populate with other characters, other times and places.

For Starskey Butler, there is an unbroken continuum between social work and creative practice. “I’m an artist and I’m a social worker but I’m one person,” they say. “There might be a technical separation but there is not a spiritual separation.” Now based in Birmingham, Butler was brought up in Wolverhampton by Ena, their unofficial foster mother. Ena is ‘Nan’ (though not biologically) and an abiding influence – a documentary where she shares her warmth and wisdom features in Thirty-Six.

Elsewhere, landscape images from a series called IN/OUT evoke the interplay between external and internal worlds while pictures made at Ena’s home touch on the ways that memory and culture shape our identities. A moving-image piece trains our gaze on the greenhouse in her garden, while a still image shows a spade belonging to Ena’s husband, another formative figure for Starskey Butler. The artist speaks of history and culture – how many Jamaican immigrants brought farming traditions from their country of origin to Britain – but they are as much metaphors for how we are nurtured and how we grow.

There are always multiple versions of any story. There is a version of Starskey Butler’s story that sensationalises pain and trauma; there are versions of their story seen through the perspective of family members, caregivers, council authorities. And there’s the version of the story they tell here, picking their words carefully as we drink tea in a quiet room away from MAC’s public areas.

“I’m an artist and I’m a social worker but I’m one person… There might be a technical separation but there is not a spiritual separation”

The artist did reconnect with their birth mother when they were 7 or 8, but it was only as an adult that they really got to know her. Access Subject (2022), an in-progress book project centred on portraiture and dialogue between the pair, was sparked by the discovery of those children’s services records. “I just went round to her house and was like, ‘I’ve got these records, shall we do a photography project?’” She agreed and they looked through the records together, speaking at length about her childhood and life before Starskey Butler was born. “After that, we finally both saw each other properly, as human beings,” the artist reflects.

Before their career as a social worker, Starskey Butler hadn’t considered delving into their own past. But working in child protection, they started to wonder about their background. “I always knew I had older siblings that had been placed into care,” they say. They also point out that “a person who has had previous concerns raised will have a ‘pre birth assessment,’ so my mother would have had some involvement with social services.” In April 2017, Starskey Butler put in a ‘subject access request’ with Leeds council, expecting to receive a single-page letter and instead finding themselves weighed down with a mountain of paperwork.

Gradually, they were able to piece together more of the jigsaw, but further questions emerged through the information missing in the redacted pages. “Visitors think I redacted them but that’s how I received them,” they say of the documents on display at MAC. “I was interested in them as objects, their textures and how they relate to the photographs.” The council sent the redacted pages, related to events that took place before Starskey Butler’s birth, through with the rest of the documentation, although there was no information contained besides the inclusion of name, place and date of birth and a court date. More intriguing than not seeing anything, these almost entirely blanked out papers remind us of knowledge just outside of our grasp.

This is a theme that recurs throughout Thirty-Six. For example in a series of images shot from trains when Starskey Butler would travel around the UK conducting interviews with individuals to assess their suitability to foster a child to whom they already have a connection, but who cannot reside with their birth parents. The smudged and fleeting landscapes are meditations on the responsibility of making those decisions. “You assess somebody’s entire life from when they were born up until that moment,” Starskey Butler explains. “You think, ‘Who am I to even be doing this?’ And you’d see someone over a long period of time each week for hours.” Moments of optimism and confidence could rapidly give way to doubt with an unforeseen revelation. It is a prolonged process where the assessor must stay open to all possibilities before finally reaching a starkly binary conclusion – a yes or a no.

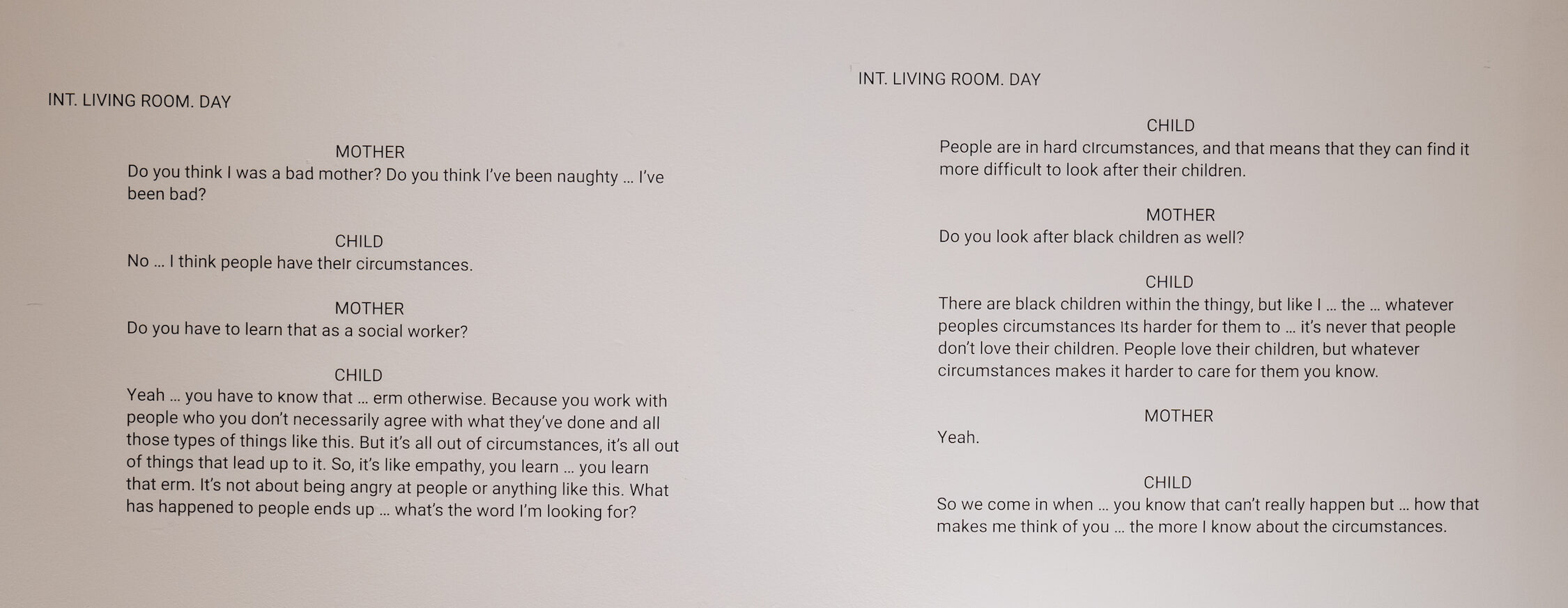

Thirty-Six takes us on a journey of deep empathy that echoes Starskey Butler’s own experiences, both professional and personal. The intensive discussions that informed Access Subject began in the same way that a foster viability assessment would – although that impartiality was impossible to maintain. In a section of the interview, reproduced verbatim on the exhibition wall, Starskey Butler’s birth mother asks, “Do you think I was a bad mother?” They reply, not as a social worker but as a child: “No… I think people have their circumstances.” In the end, circumstances are all we have, the sum total of our stories, layer upon layer, that make us who we are.

Marley Starskey Butler: Thirty Six is at Midlands Arts Centre, Birmingham, until 28 January