All images from The Fury, 2023 © Shirin Neshat. Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery

Content note: this article contains mention of sexual assault

The Iranian artist discusses the multifaceted violence – and resistance – in The Fury, a set of powerful nude portraits and dance-inspired film

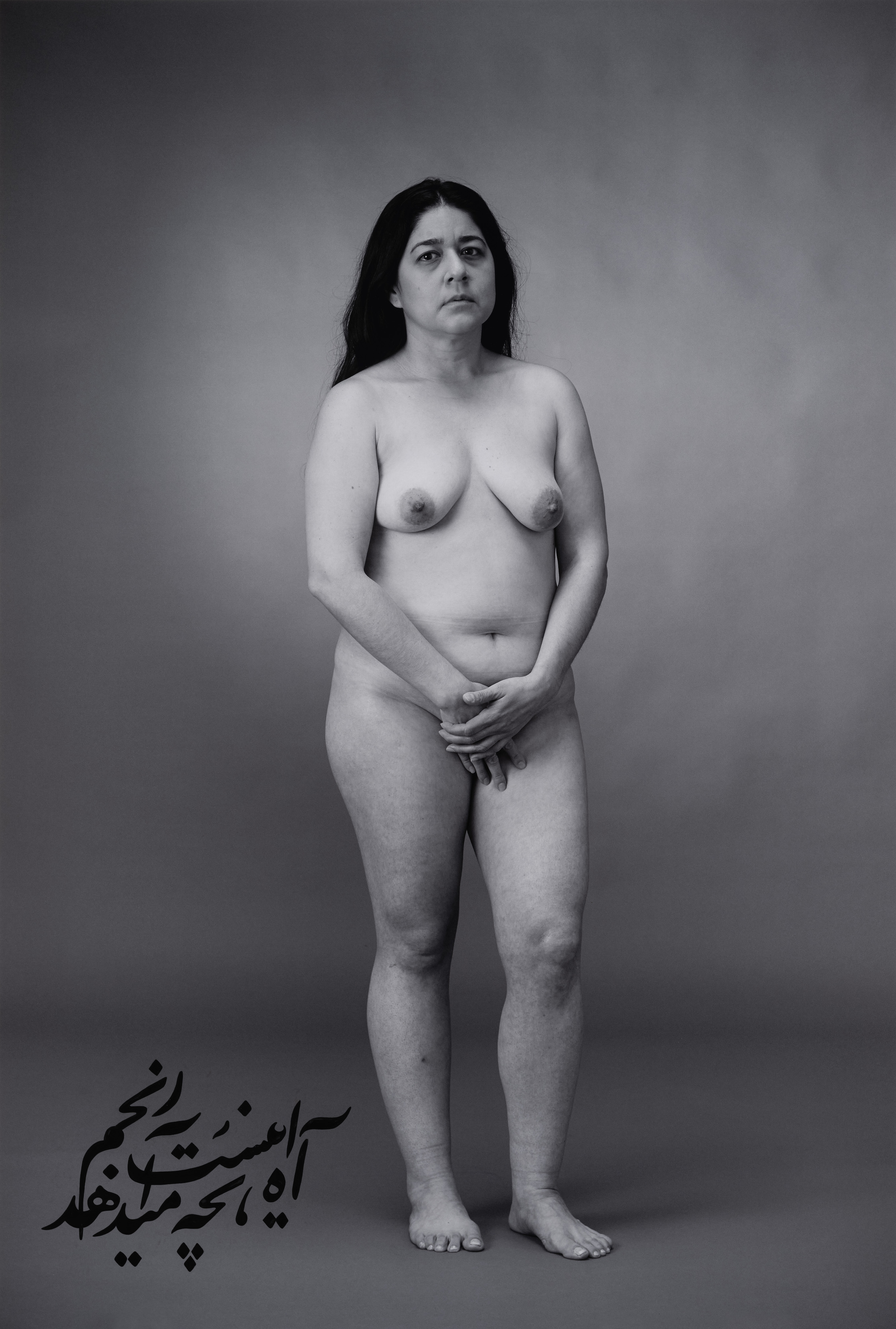

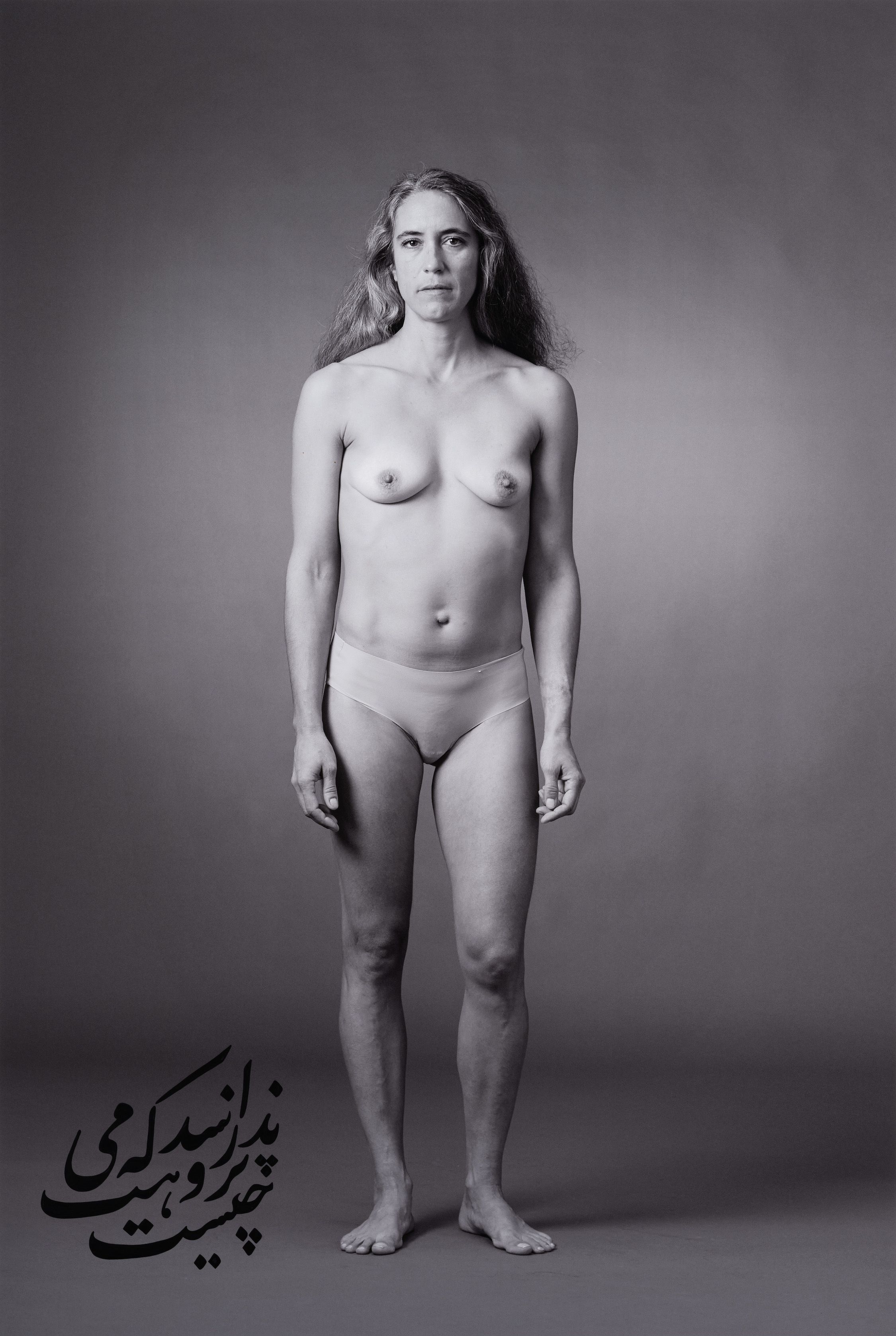

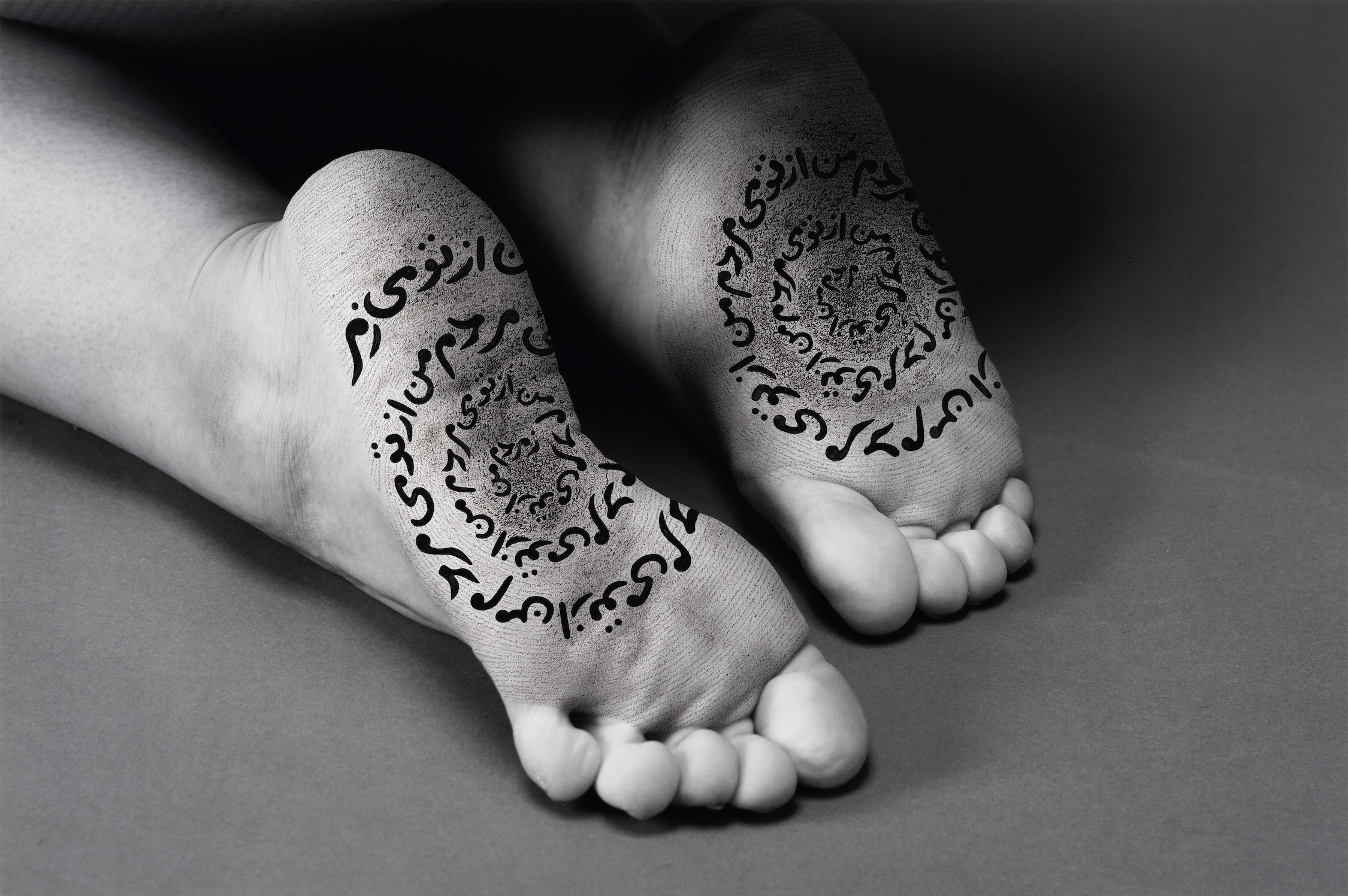

For thirty years, Shirin Neshat has made lens-based art which takes the theocratic politics of her native Iran as its starting point, using song, dance and dream to imagine futures beyond segregation and repression. Women of Allah (1993-7) saw her make portraits of veiled women holding assault rifles, a vision of ominous ambiguity in the wake of Neshat’s return to Iran from exile in 1996. It was also her first time using inscription on her photographic prints – sometimes enlarged in single letters she calls logos – by including verses by Iranian poets Forough Farrokhzad and Tahereh Saffarzadeh. Neshat has continued this with her nude portraits in The Fury, again tapping into the rich history of feminism’s relationship with inscription and writing the body – even when such expression is outlawed.

Other works have used doubling as a way to explore gender difference and also enable a unique, two-channel display method for her artist films, where audience members are caught between two screens in the gallery space. In The Fury film, a woman dances before a circle of military-clad men, who leer at her movement and sparkling clothing, the threat of sexual assault lingering. She then emerges into the streets of modern-day Brooklyn, where she passes graffitied underpasses and street vendors, her thick eye make-up matching Neshat’s trademark. The New Yorkers look upon her with a mixture of intrigue and fixation before, suddenly stripped of her elaborate dress, she is joined by other women who share in her screams of pain, defiance, and eventually, a dance of empowered destruction.

Here, in a conversation which took place at London’s Goodman Gallery during The Fury’s presentation, Neshat discusses her new approach to portraiture, her artist-activist status, and the painful relevance of her work today.

Can you start by telling me about The Fury, especially the decision to write on the photographic prints?

Everything I do is about woman, but also women’s bodies. This work is a departure in terms of the images but also the use of calligraphy. In all the previous series I’ve done, especially Women of Allah, the figures are more iconic – they have always been under the veil. The women were also armed. The veil is a symbol which shows oppression, but also faith and, for some, a symbol of independence. My subject was the female body in relation to political ideology, religious values and the submission of women to fanaticism. And so the poetry and literature I used was very specifically about the 1979 revolution.

The Fury is almost one hundred per cent opposite. It unveils the woman. It is no longer about woman in relation to religious or political ideology, but woman as a subject of desire – but also violence. The way that the female body provokes temptation, and equally can be a subject for violence. The calligraphic writings are almost microscopic, because I felt that what became more important in terms of tension is the gaze of the woman. I didn’t want to overwhelm it or dominate it with big calligraphy. I started with straight lines of poetry, but then they started breaking. It’s almost the collapse of words – a much more emotional and expressionistic use of calligraphy that is legible, and then not. The style punctuates the emotions and theme; it’s not just arbitrary. The photographs become sculptural.

And so what is the relationship between the bare and the inscribed body?

Several of the photographs represent women who are completely confident, defiant, proud, feeling beautiful with their bodies regardless of size, age or ethnicity. And so the logos on the prints are poetic extracts of poetry which extend these themes. It by no means is about pain; it’s about the absence of pain.

At the beginning of the film, the woman is dancing seductively: she’s comfortable, she’s in control, dressed almost like a prostitute. But then she goes into the street and people are looking at her, but when she sees the man again she is naked. You see the woman as a seducer, but at the same time she is a victim. So in different mediums and languages, we’re telling the same story.

“When it comes to activism, you distinguish between what is wrong and what is right; who is evil and who is good. In the art world you don’t”

There is very little touch in the film, even though sexual violence is implied. How does dance negotiate this?

Dancing in public was completely forbidden, and so has recently become a symbol of protest in Iran. The Fury was made before the Woman, Life, Freedom protests [beginning in September 2022], but I’ve studied dance for a long time. Dance is a pure expression of art because it is very ritualistic. There’s an intention – a meaning. It’s not just for entertainment. The power of dance is the use of the body to express yourself. That’s the same in India and the ceremony of African dance too. And so this dance on the street is a dance of protest and of showing anger. But for those men, Persian dance is a form of entertainment.

Something that recurs in The Fury is the act of being observed – by the men or later when the woman goes into the streets. How do you relate that to the implicit observation within photography?

There is an element of choreography, even with the photographs. I begin each series with a rough plan. I asked my subjects to improvise, but even that improvisation is choreographed; I am going after what they’re doing with their bodies, and I’m catching it as they do it. I don’t instruct. In Women of Allah, the hand over the mouth is very important – the woman’s inability to speak, the submission. For me, it’s the body’s simple postures or gaze which are dance-like. You can convey a lot with them and they speak to me in a very emotional way – and I trust my gut when shooting.

This was the first time that I’ve ever photographed nude subjects. I was really concerned that they would feel uncomfortable. But they were so comfortable. They said, ‘We don’t have to wear our underwear.’ This is from Iranian women to Indian women. That gave me chills, because they knew that the work’s subject was sexual assault. I really believe that every woman has been molested sexually at some point in their lives – I have – and men too, we just don’t talk about it. And here they were being photographed and being really honest about it. It was really empowering to be around them.

What about the military context of The Fury?

The Fury is about patriarchy. It’s about male power. It’s about men in uniform. It’s about all the countries where men in uniform rule. When she’s dancing, the men look at her with the same intensity as when she’s on the ground. The expression doesn’t change, and that is really important. These men are looking at her both as a seductive animal, but then as this dirt on the floor.

Ever since I was a child, I’ve been very afraid of men in uniform. I’ve had a lot of trouble with the Iranian government and getting out of the country. From airports and immigration to police cars, I have grown up with fear. I haven’t been back to Iran since 1996. And in The Fury, the uniforms are not Iranian, they are universal. It could be the FBI, it could be the Russian soldiers. It’s symbolic.

How does The Fury reverberate beyond the gender and military contexts?

I think art can have a lot of power in this culture. We’re talking about a common humanity; an African or Asian or white person can relate to this condition of a woman in New York. They could relate to her pain. The victimisation of people and the pain is contagious. Israel, Palestine, Iran. And I believe in making work that speaks to people outside of art galleries and the commodification of art. I love filmmaking because it refuses to be an object. But my photography is just as loud as the video, though it is nevertheless an object to buy.

I’m also an activist. And I’m very careful about how I distinguish between my art and my activism. I don’t want to just belong to the art world. I’ve been active in protests, the media, organising, from hunger strikes to events and exhibitions. When it comes to activism, you distinguish between what is wrong and what is right; who is evil and who is good. In the art world you don’t. And I think that makes a lot of people uncomfortable, but I refuse to do that. I don’t want to make work that points the finger, but as an activist, I do.

Shirin Neshat, The Fury, is at Fotografiska Stockholm until 18 February 2024