Aïda Muluneh, Star Shine Moon Glow, 2018. From the Series Water Life.

Photograph, inkjet print on paper; 800 x 800mm

Commissioned by WaterAid and supported by the H&M Foundation. © Aïda Muluneh

A World in Common presents 36 artists using photography to reimagine Africa’s place in the world. Here, Bonsu shares his highlights, insights and the show’s historical contexts

Introduction

Probably the most dominant narrative that exists in relation to African photography is that Africa is often constructed through a lens – the idealistic, the exoticisation of its peoples and landscapes. That existed in the 19th century, in the very early days of photography, and exists all the way through to the present.

The intention for this exhibition is to address the ways in which artists are countering those fixed narratives, but also using photography as a tool to activate discussions around the telling of history. It isn’t just about dealing with contemporary photography, but the archive, and this incredibly deep, rich and problematic colonial archive that many of these artists have inherited.

Queens, Kings and Gods

The work of George Osodi is probably the most emblematic in this section. It’s a series that looks at individual, traditional rulers across Nigeria, all of whom now have a ceremonial position as custodians of cultural heritage, but no longer hold the same kind of political agency that they would have had in the pre-colonial times. It’s an attempt to look at the ethnic diversity of Nigeria, which of course, as a result of being colonised by Britain, was amalgamated into a country.

You can see the pomp and ceremony, but also the grandeur of these as royal portraits existing in the present, but speaking about a tradition that was perhaps lost within a colonial encounter. This was an attempt to think about starting Africa’s narrative differently. Instead of starting with this narrative of colonialism and slavery, which is ever present, we think about some of the customs and traditions that predated that encounter.

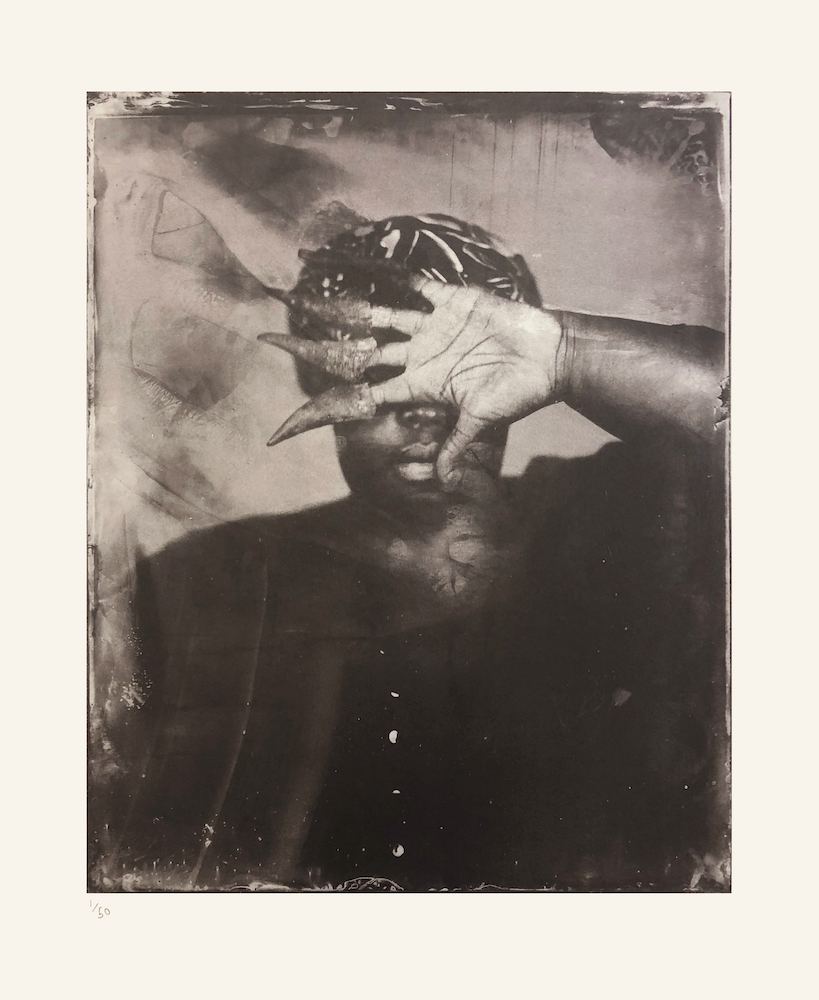

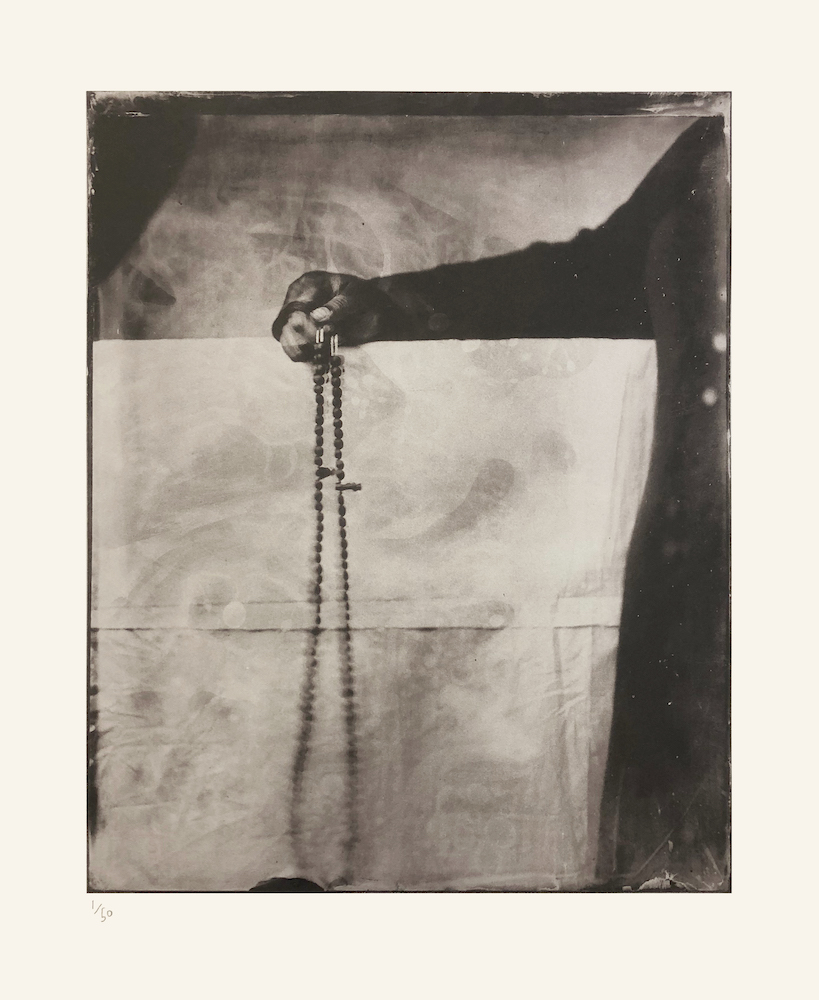

Spiritual Worlds

This particular room is very demonstrative of the artists all engaging with questions of spirituality in such different ways, whether it’s spirituality through the lens of the body and devotion, or this existential possibility of engaging with one’s ancestral heritage. Or thinking about the problems of isolation and togetherness in relation to spirituality, spirituality in relation to ideas of the landscape and what it means to memorialise one’s ancestors.

An artist that’s become very emblematic of these discussions in the UK, as a result of her tragic death in the Grenfell tower, is Khadija Saye. In one image she has lemons covering her face, and there are connections between lemons and the idea of domesticity, female labour in the Gambia, but it’s also because she loved Beyoncé’s Lemonade. So it’s an attempt to think about Gambian ritual, but in a deeply personal way.

When we thought about Spiritual Worlds, there was this idea that spiritual worlds are often constructed in spaces of private contemplation. It can be about a collective spiritual practice or belonging to a particular religion, but I think more importantly for many of these artists, it’s a personal journey, and that’s what we didn’t want to lose sight of.

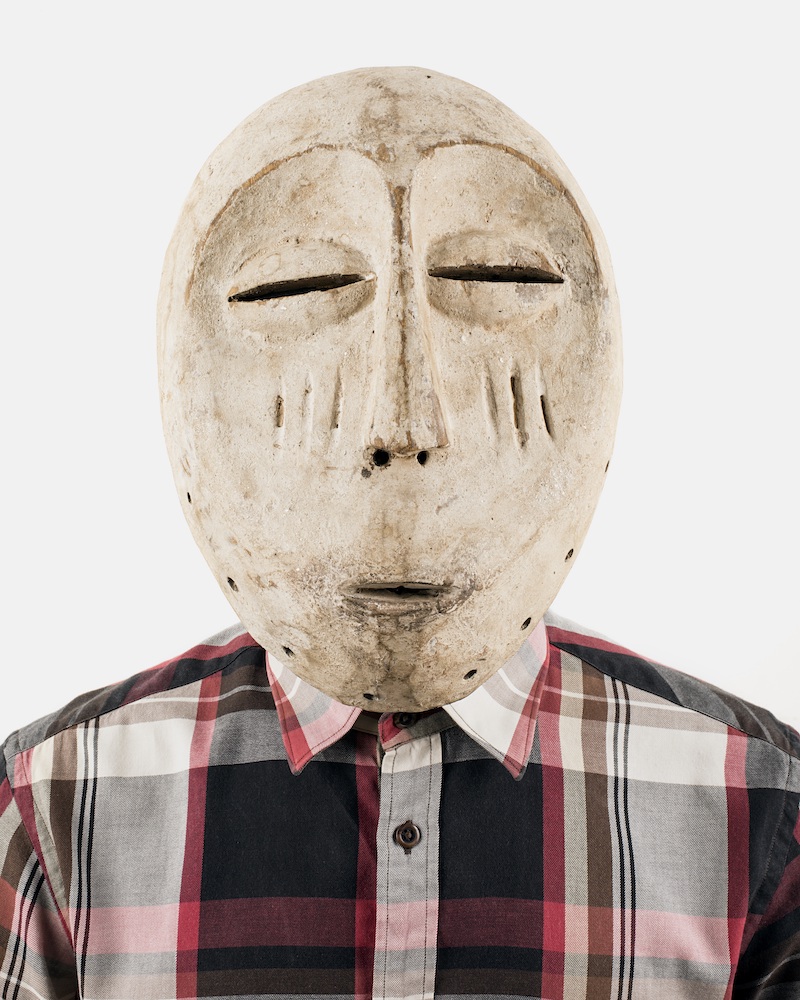

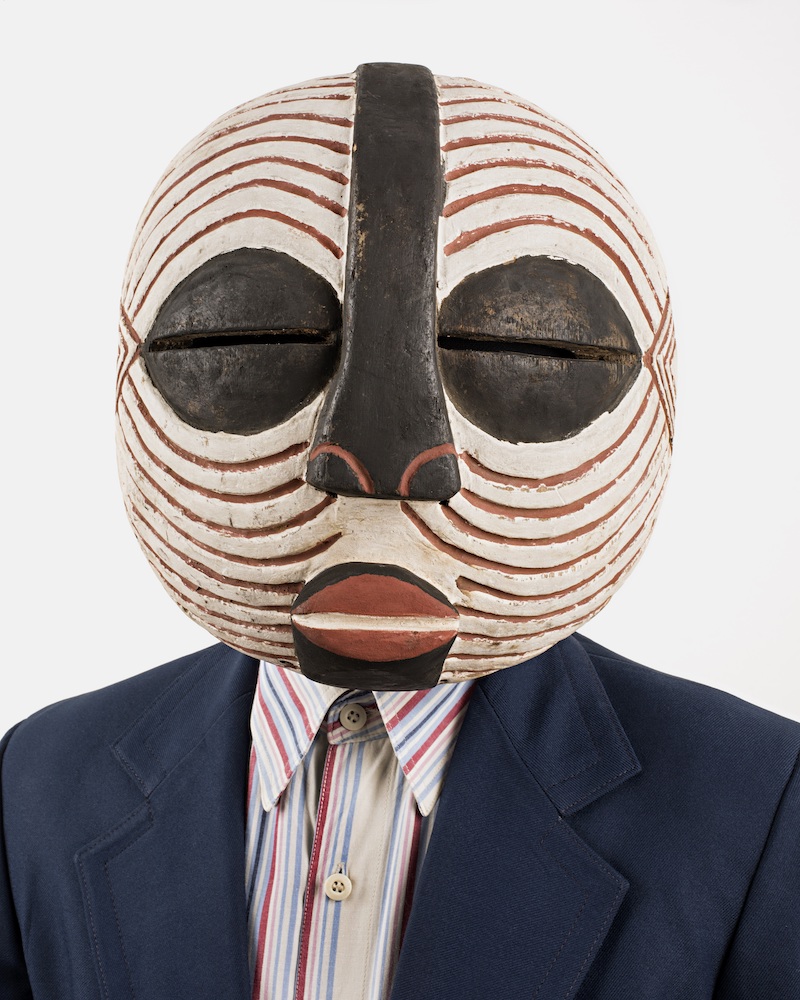

Worrying the Mask

Many people assume that masks are a way of hiding, but what many of these artists demonstrate is that masks can also be used to reveal. So in many instances in traditional African cultures, when one is wearing a mask they’re no longer regarded as a human subject, but as a spiritual entity.

There’s also something ironic about the way that masks have now become somewhat detached from those legacies. Here Emmanuel C. Bofala is thinking about the mask as a ubiquitous signifier of global African identity, and how particularly in Rwanda where he’s based, people will often wear their Sunday best to have their passport photos taken.

When we think of questions around the migration crisis and how that impacts our society, it has a very detrimental impact on individuals who are unable to travel freely. And in this work, it’s obviously a very ironic take on the idea, but very powerful when you think about the layers that uphold this idea of the passport photo, particularly within the history of photography.

The Living Archive

I think what was important in this section was not to merely reflect on the colonial legacies of photography, but think about the ways in which artists had reimagined those legacies. Often contemporary artists are asking us to rethink the present in different ways, and Sammy Baloji is an artist who’s so emblematic of that.

This particular series, Mémoire, was built upon an archive that he discovered that was pulled together during the period of Belgian colonial occupation. What you’re seeing is many indentured labourers, effectively, completely without agency and without the ability to determine their own representation. But photography becomes this tool for registering these acts of colonial violence.

Quite often, when we think about the colonial histories in the context of the UK, we think primarily about a kind of a symbolic violence, but we don’t always think about the ways that it affects wider issues of climate change, infrastructure, questions around sovereignty. So all of those issues that are at play in this work are important for us to look at as a result of where we are now – they’re not divorced from our present.

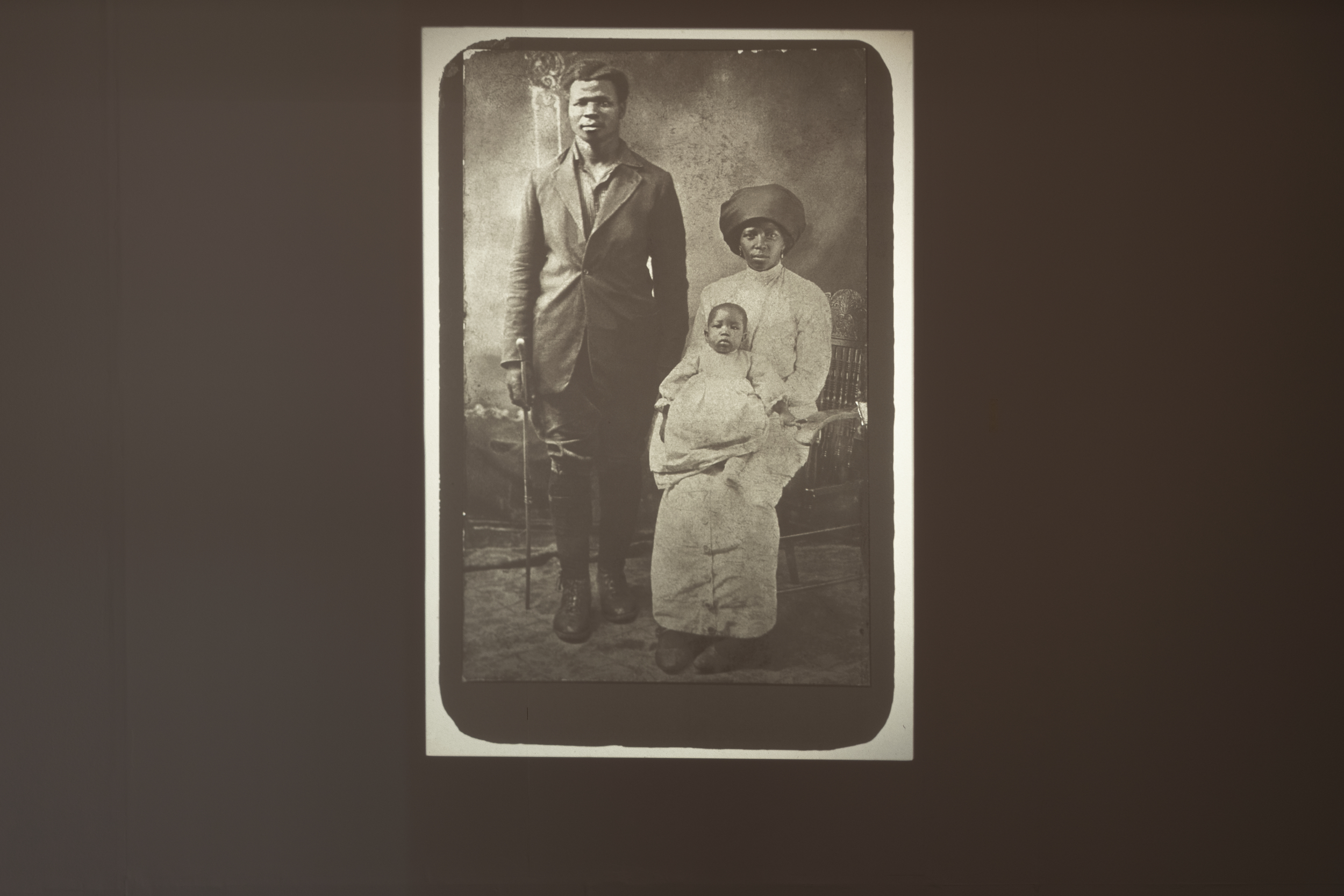

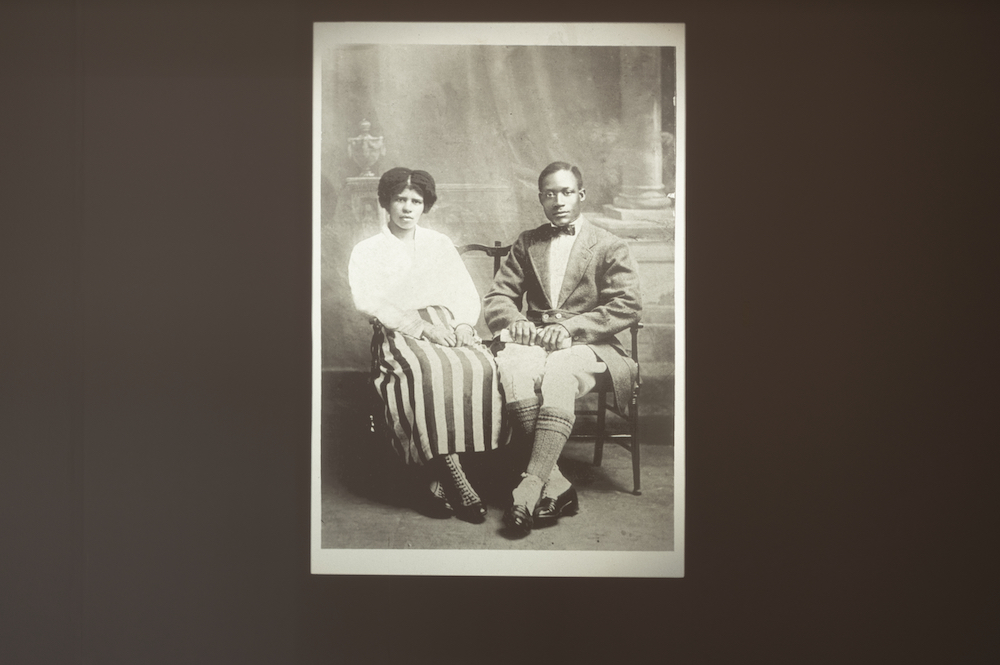

Family Portraits

This section was an attempt to mine a different narrative of the family portrait. I was very conscious of the fact that, particularly during the 1840s when photography studios were being set up, most of the people that had access to traditional photography studios would have been middle class or upper middle class families, who had the privilege to fashion their own identities. Often this made them slightly divorced from many of the social and political realities that the majority of people were experiencing at the time, and that’s certainly referenced in this work by Santu Mofokeng, The Black Photo Album.

Typically, when you look at the work of Mofokeng, you’re looking at Black South African subjects wearing Victorian dress, many of whom were associated with the Christian missions. And as a result, were able to transform the way that they were perceived by others. But what of course happens as the 20th century unfolds and many of these people’s lives are socially, politically, economically transformed. So it’s fascinating to think about the politics of studio portraiture, because it’s about looking at all of the different uses of the family portrait and the family photo album.

There was a really interesting challenge with this particular section of the exhibition, to look on one side at the history of studio portraiture, and on the other side at the history of the colonial archive. To my mind, it was about really delving into those juxtapositions, even at the risk of not providing a coherent narrative, because there isn’t one. This is a history that’s constantly becoming unfixed, often by the artists themselves. This kind of unravelling of time and memory is so important within this exhibition.

Shared Dreams

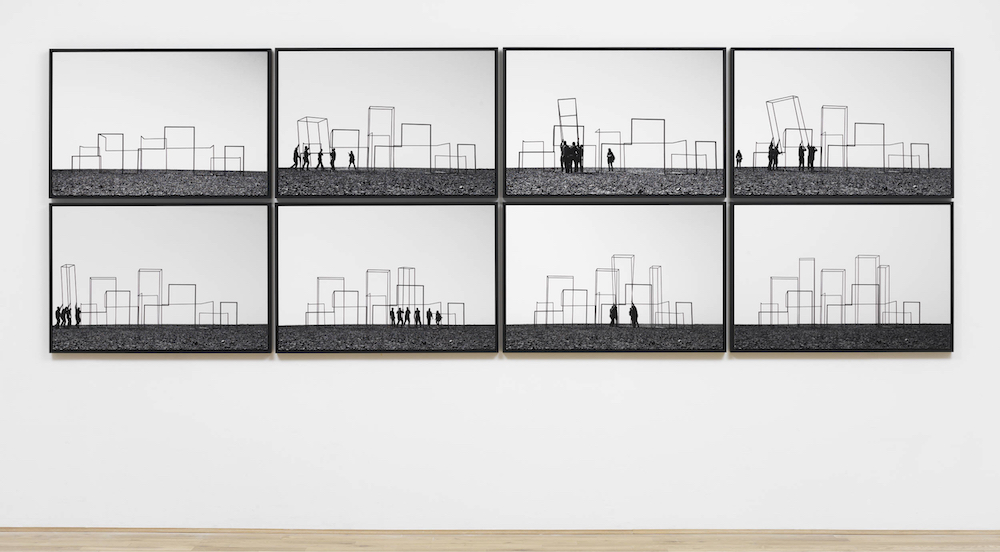

Kiluanji Kia Henda’s A City Called Mirage is a very good example of work that was initially considered as a kind of conceptual installation that was documented through the medium of photography, but it’s absolutely as much a sculptural project as it is a photographic one. It’s derived from the artist’s recognition that after the civil war in Angola, there was a shortage of affordable urban housing. This led to a situation in which the city that was rising, that almost looked like it was fashioned after Dubai, had nothing to do with the social reality of its citizens.

And that’s where we wanted to take people with this next section, which is not about Afrofuturism as projecting a fantastical reality in which Africa is viewed only through a fantasy lens, but about how artists are projecting their own futures. What they think African might be – rooted in the present and rooted very much in the contingent social, political realities that they face.

If the early section is the answer to colonial photography, ethnographic photography that fixed African subjects within a lens of exoticisation or difference, this section responds more directly to contemporary representations of Africa. This is through aid organisations, through documentary photography and other kinds of media that sometimes serve to create complex narratives, but often serve to reassert what we think we already know about the continent.

Epilogue

What I wanted to do with this exhibition, essentially, was to not have Africa necessarily be the only anchor. I was thinking about the ways in which artists were addressing these very global issues, whether it’s spirituality, urbanisation, the climate emergency, but from an African perspective. What I wanted to suggest is that by doing that, we gain a more expensive understanding of our humanity. But in order to do so, we have to also undo or unlearn some of the assumptions that we have around what Africa represents.

A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography is at Tate Modern, London, until 14 January 2024