All images © Oliver Chanarin. Commissioned and produced by Forma with 8 UK organisations, and supported by Arts Council England/Art Fund/Outset Partners.

Two years since his dramatic separation from artistic partner Adam Broomberg, Oliver Chanarin reflects on collaboration, consent, and his new book

In February 2021, Spanish gallery Fabra i Coats mounted The Late Estate: Broomberg & Chanarin – an ostensibly posthumous exhibition celebrating the success of an artistic collaboration between Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin which had lasted more than two decades, but was now coming to an end. “The duo have legally, economically, creatively, and conceptually committed suicide,” announced South Africa’s Goodman Gallery at the time. The ‘loss’ of the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize winners, and the subsequent display of their joint estate, prompted considerable discussion across the art world – including an obituary, of sorts, published on BJP’s website. Yet, over two years later, in a sunlit studio in east London, Chanarin sits before me, very much alive.

The photographer is here to discuss his new book, A Perfect Sentence, but the creative “suicide” of his partnership hovers pointedly at the edges of our conversation. Eventually, I have to ask – how does he feel about the breakdown of the relationship and, on reflection, would he describe its demise in the same terms today? “Well,” he replies, slowly, “suicide is a decision, and I don’t think we made a decision – the partnership collapsed.”

This frank description is mirrored in the text of A Perfect Sentence. In a lengthy, meandering and insightful essay, Chanarin likens the professional divorce to two small brain cells which, each starved of oxygen, eventually wither. “I didn’t know how to be a photographer anymore,” he says, with a surprising air of vulnerability. “How to make the work was truly a mystery to me, because I’d been existing within these boundaries.”

So, in early 2022, when Chanarin set out across the UK in search of collaborators to become part of A Perfect Sentence – a project inspired by the division surrounding Britain’s exit from the European Union, the pressure of Covid-19 lockdowns and the rise of identity politics – his aim was twofold. First, through a combination of instinct and curiosity, the photographer sought to leave behind the structured nature of his collaboration. Second, he hoped to escape the echo chambers of like-minded opinion within which so many of us can find ourselves trapped.

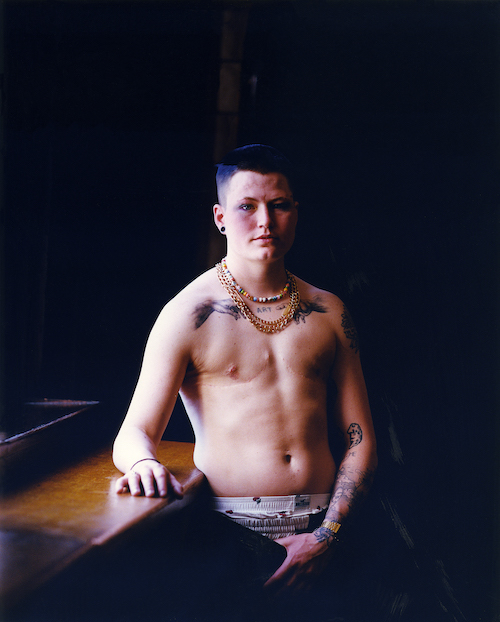

The project became Chanarin’s passport to venture beyond these enclosed environs, granting him access to the lives of migrant workers collecting potatoes for gourmet chips, to meetings of the Casualties Union – which, since 1942, has been staging disasters to teach emergency preparation – and to couples who champion adult breastfeeding as a means to emotional wellbeing. Working with eight arts organisations across the UK, the photographer met groups at the heart of each institution’s community, leading to a scattered record of human encounters that speak to a modern British identity in flux.

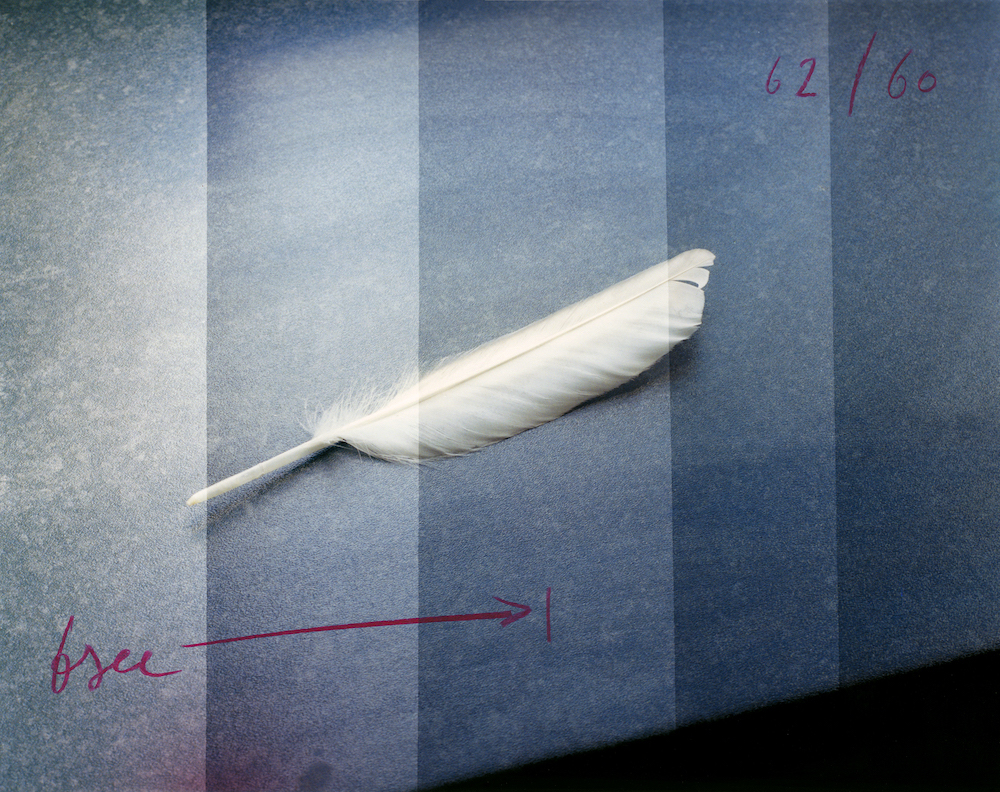

The many faces of Chanarin’s collaborators are characterised by his approach to the images themselves. Incomplete but beautiful, filled with errors but with the possibility for change, they retain his notes and scribbles. The latter is a feature that, he admits, is partly related to his lack of experience in the colour darkroom, which occasionally presented him with a dilemma.

While Chanarin strove to make his image-making collaborative, he struggled to resolve the tension between the expectations of his collaborators and his use of their portraits. Once an image is made by mutual agreement, and once that moment of collaboration has passed, to whom does the image truly belong? To the sitter, whose likeness it shows, or to the artist, who develops, prints, frames and recruits it to their own world view?

All of this, Chanarin acknowledges, is a question of consent – a topic I am almost as keen to discuss as I was to address the spectre of his collaboration. Again, the reason for this lies in the essay that accompanies A Perfect Sentence in which he writes of a workshop he conducted in the north of England – one that ended with the involvement of the host venue’s lawyers. “In retrospect, it fills me with horror,” the photographer says, tentatively.

He goes on to explain how, while teaching large format photography to teenagers, he took the portrait of a helpful older woman, whom he mistakenly believed was not a workshop participant but an assistant provided by the venue – an arts organisation he declines to name. He posted the image to his Instagram with a message of thanks. “The next day I looked at my phone and I saw that she had written to me directly to say ’take it down’,” he recalls. “I deleted it, said sorry, and I thought that would be the end of it.”

“I don’t think Adam and I could have made any of the work that we made in today’s context. I might even be finished with working in the documentary mode entirely”

It was, however, very much not the end of it. The photographer describes being called to a meeting with the venue, where he was told he had breached their safeguarding policy, and that their collaboration was subsequently over. “It’s an experience that came to shape everything that happened after,” Chanarin says. Evidence of this can be found in the opening pages of A Perfect Sentence, where lines from the safeguarding documents are printed: “Don’t reduce me to tears as a form of control… Don’t allow my allegations to go unrecorded… Don’t capture my image without consent…”

Perhaps inevitably, our conversation turns to wider issues of access and representation, and to who has the right to make images of whom. Chanarin’s thoughts on the topic are long, considered, and clearly impacted by his error. “I don’t think Adam and I could have made any of the work that we made in today’s context,” the photographer admits, referencing early projects in psychiatric hospitals and refugee camps. “I might even be finished with working in the documentary mode entirely.”

It is a conclusion that, Chanarin explains, his work on A Perfect Sentence allowed him to reach. The project has reshaped his understanding of his gender, race and age, and forced him to consider how the space he occupies – both physically and metaphorically – is intrinsically linked to his role in documentary imagemaking. “I think if you feel that you’re moving through the world in a neutral and frictionless way, that is cause for concern. It’s a reason to pause and to consider what your impact is,” he explains.

Chanarin raises concerns that this final statement may read as somewhat glib – and perhaps he is right – but in the moment he sounds purposeful and sincere. As I leave his still-sundrenched studio, I reassure him of this – speculating privately whether, despite his anxieties, these revelations may become the very things that finally lay past partnerships to rest. More than two years on from his ’death’, we may be soon witnessing the resurrection of Oliver Chanarin.

A Perfect Sentence by Oliver Chanarin is out now (Loose Joints). An exhibition of the work, produced by Forma, is at the Museum of Making, Derby, until 3 September