All images © Vic Bakin

Developed in his bathroom, Ones To Watch winner Vic Bakin’s images offer nostalgia in a time of war

Vic Bakin was born in 1984, in a tiny village in Turkmenistan that “is probably now non-existent”. Raised near the Carpathian Mountains in western Ukraine, Bakin moved to Kyiv 13 years ago, where he lives today. During this life of migration, Bakin found photography. Although, he laughs, there was no “I saw Edward Weston and I began” moment.

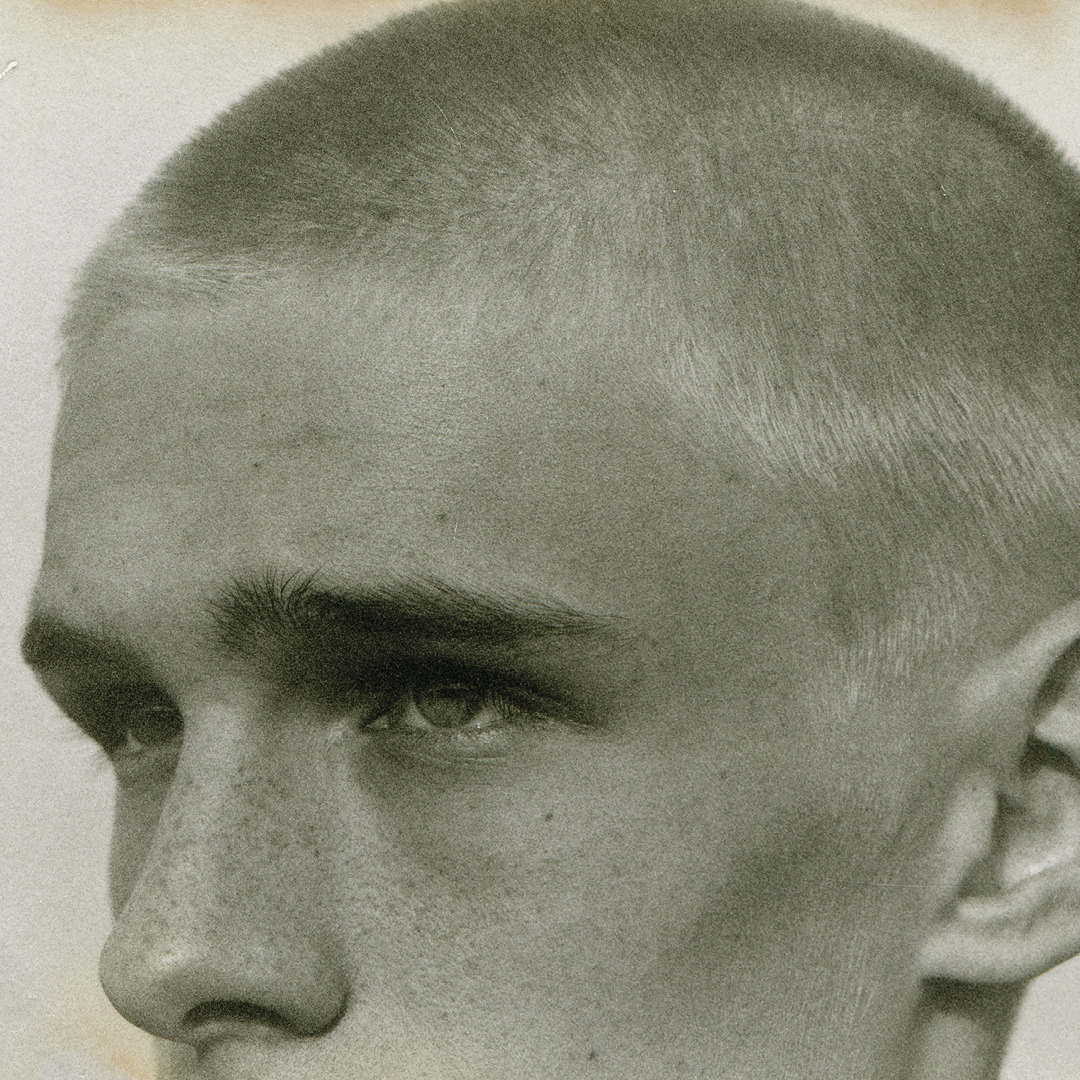

Without pursuing a formal education in photography, Bakin started making images of Ukrainian youth (often young men and often for fashion brands), queer communities and rave culture. While each group was different, Bakin was drawn to the shared experience of mystery and contradictions that coming of age brings.

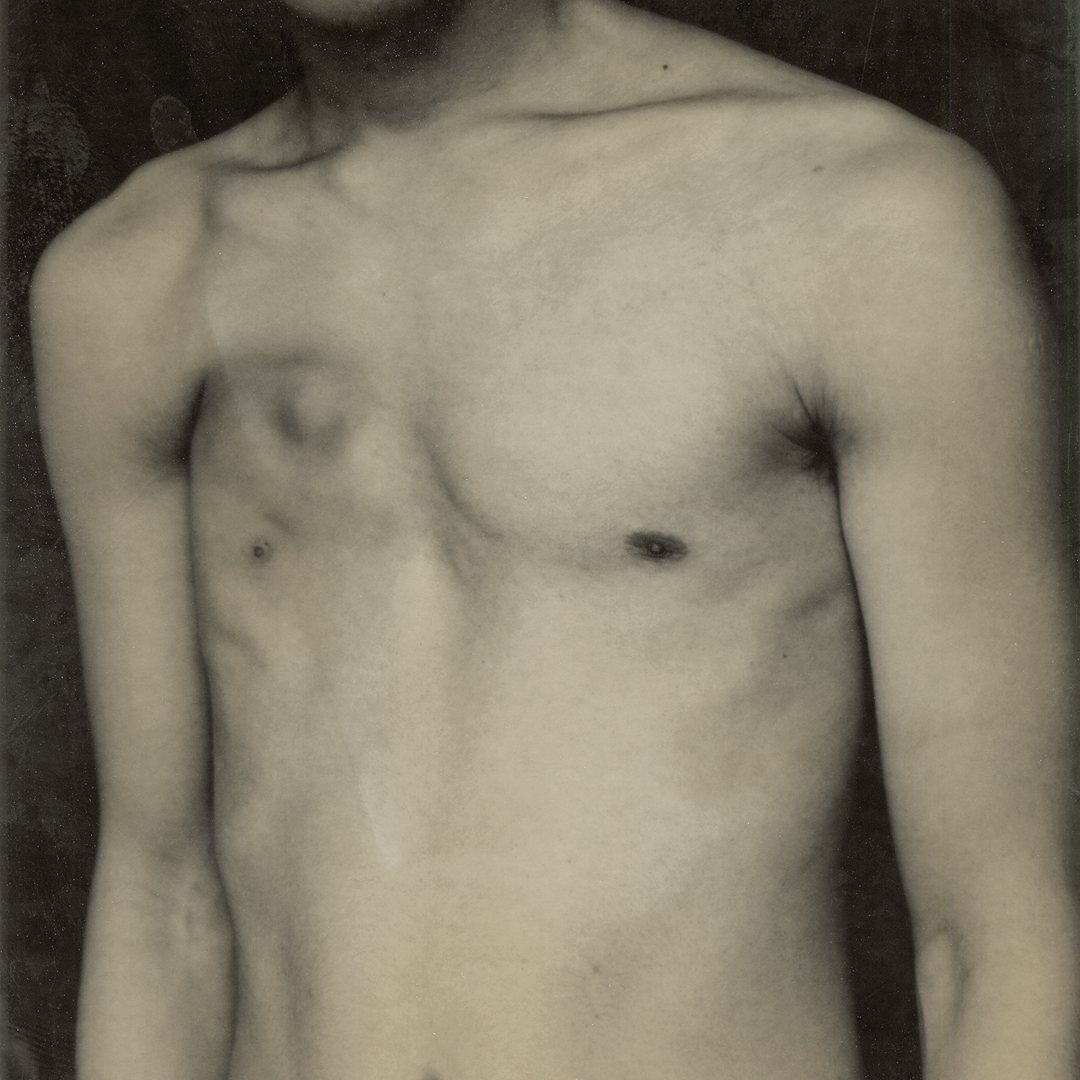

Epitome, his most recent work, began from a similar place. Originally a poetic exploration of youth and masculinity, the work pulled in a new direction when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. The photographs of tender bodies and tranquil land became less about masculinity and more about belonging and the fragility of it amid chaos. Yet, despite the grief that now entwined around Epitome, Bakin found solace in rediscovering faces and places from the past.

When asked whether it was nostalgia, he frowns but later returns to the idea: “Maybe it is.” If it was, it would not be amiss, nostalgia being a word from the Greek ‘nostos’ (to ‘return home’) and ‘algos’ (meaning ‘pain’). For a work now inescapably about what it means to belong in a time of war, it seems all too fitting.

Epitome began a short time after Bakin started to develop and print his images in a DIY darkroom in his bathroom. In the darkness and the safety light’s red glow, Bakin found a “whole new world”, womb-like in its reassurance and comfort; a psychological sanctuary that distanced him from the air-raid sirens outside. This – combined with the uncanny but life-affirming act of bringing something into the world – was Bakin’s escape.

However affectionate and delicate the images in Epitome are, they also bear what some might call imperfections. Far from being superficial gestures, these marks came from Bakin finding his way in the darkroom. The use of fingers instead of tongs made the paper crinkled and scratched. Muddy patches were left behind by exhausted chemicals, and brown shadows from using a dripping tap as a timer. Other blemishes evidence moments of impatience.

“Bakin has used the imperfection and fragility of a process… as a striking and sensitive response to the monumental shifts in his life and others’ caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine”

“You would probably call it unprofessional,” Bakin says, modestly. However, the imprints are symbolic of how Bakin wounds his photographs, in a palpable and poignant allegory for the violence enveloping Ukraine.

“Bakin has used the imperfection and fragility of a process… as a striking and sensitive response to the monumental shifts in his life and others’ caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. His never-ending search for beauty feels more needed than ever,” says Ukrainian photographer Anton Shebetko, who nominated Bakin for Ones to Watch. He was also put forward by photographer Kalpesh Lathigra, who describes his images as holding “a tangible air of both fragility and escape that ultimately come from the cocoon of the darkroom. Together they speak to the painful effects of war but also the meditative nature of printing – time elongated.”

When asked if the end of the war will mark the end of the Epitome project, Bakin replies: “Maybe, I don’t know. You never know what will happen next.” For now, the work is ongoing.