Photography by Stefanie Kulisch

This article first appeared in the Money+Power issue of British Journal of Photography. Sign up for an 1854 subscription to receive the magazine directly to your door.

Interrogating the unseen infrastructures that govern our lives, Trevor Paglen’s technology-driven practice has led him to deserts and oceans across the world, and even into space. But it is here, in his two-storey studio in Kreuzberg, Berlin, where his ambitious ideas begin and end

In 2014, American artist, geographer and author Trevor Paglen was working on Citizenfour, a documentary about Edward Snowden and the NSA spying scandal. In fear of being subpoenaed by the FBI, the team edited the film in a converted apartment in Berlin, Germany. When the project wrapped, Paglen decided he wanted to stay. The creative spaces in Berlin were bigger and afforded him the possibility to “do more”, he explains. In 2015, Paglen took over the Citizenfour editing headquarters, located in the central neighbourhood of Mitte, and turned it into his first studio outside the United States. Two years later, however, the apartment’s three rooms no longer cut it. “We needed more space because we were doing more ambitious projects,” he says. Paglen relocated to Kreuzberg, a popular neighbourhood south of Mitte, to a two-storey, ivy-covered brick building with a cellar, nestled in a quiet courtyard, where he still works today.

The building, as is the case with many in Berlin, is steeped in history. It was built as a factory, most likely for canned food, and used to be four storeys tall, although the top two were destroyed during the Second World War. Under Paglen’s supervision, the cellar was renovated to function as a multipurpose “messy” studio, where he can construct photo sets, stage performances, paint, and experiment with materials. It also functions as a storage space for exhibition copies of his work. The ground floor comprises a kitchen, a desk and computer-filled production room, and a small library. Upstairs is divided into a private room for the artist and a communal space with a large desk and a sofa. A few days before our visit, this room was used to host a private screening of a work-in-progress for an audience of friends.

Over the course of a year, Paglen – known for creating works that interrogate the often-invisible networks and infrastructures that govern our lives – estimates that he is in Berlin for about one and a half weeks a month. He divides the rest of his time between New York City, where he officially lives, and producing projects in the field – often in the deserts of California, Nevada and New Mexico. As such, he collaborates with people around the world and maintains a small studio in Brooklyn, as well as what he calls a “depot” in California: a van loaded with equipment that he stores on his father’s ranch. “I usually fly in there and can drive wherever [I need to go to shoot],” he says.

When he is in Berlin, “we’re usually pretty hardcore [at work] on a project or multiple projects,” Paglen explains. He sleeps in the private room on the top floor of the studio, and works seven days a week. “I’ll get up, get a cup of coffee, and get right to it,” he says. “I try to get out for an hour or two to go to the gym, but I’m usually working pretty late.” Indeed, his days in Berlin start at around 10am and finish 12 or 13 hours later, “because California [where some collaborators live] doesn’t really wake up until it’s 6 or 7pm [here]”. He works on the weekends, “because I can do more focused work, more of the intellectual work then”. When speaking, Paglen shows no signs of self-pity for the heavy workload; his energy and affability make it clear that he loves what he does, and he is totally committed to the process, no matter how intense it might be.

“I like to live with something before I put it out [into the world]. I want to see if it continues to hold my interest. Especially for an artwork that somebody might buy and live with, I want to make sure that I want to live with it before suggesting that someone else might want to.”

Testing, testing

Paglen’s photographs and films are primarily shot elsewhere in the world, but Berlin is where his ideas germinate and artworks take their early shapes. “The crux of [what we do here] is pre- and post-production,” he says. “Figuring out what we want to make, and then figuring out the plan for the project.” It is in Berlin, in collaboration with his team – Daniel, his studio director and cinematographer; Eilis, a photo editor; and Leif, a programmer and software engineer – that Paglen tests his ideas to see if they can be realised and turned into fully fledged artworks.

Previously, such ideas have included launching an ultra-archival disk containing 100 photographs into space. Titled The Last Pictures (2012), the project is memorialised via a miniature replica of the rocket that took the artefact into space, sitting atop a bookshelf in the common area upstairs. On the opposite end of the shelf – which is dedicated entirely to a smattering of objects related to projects past and present, each of which Paglen patiently explains with a healthy mixture of excitement and earnestness – is a small turquoise glass cube, a proof of concept for his installation Trinity Cube (2015) in Japan. “It was a commission to make a public artwork for the exclusion zone around Fukushima,” he explains. Paglen wanted to create a giant glass cube made from broken and irradiated glass. This was collected from the exclusion zone and fused together with Trinitite, a glassy mineral formed out of sand in New Mexico when the first atomic bomb was detonated in 1945. He tested the idea back in Berlin: “It was, like, ‘What happens when you fuse a bunch of glass together that is broken and that we just kind of found?’,” he recalls. When the test succeeded – resulting in the cube now on the bookshelf – the project could go into full-scale production.

“Projects are always ongoing.”

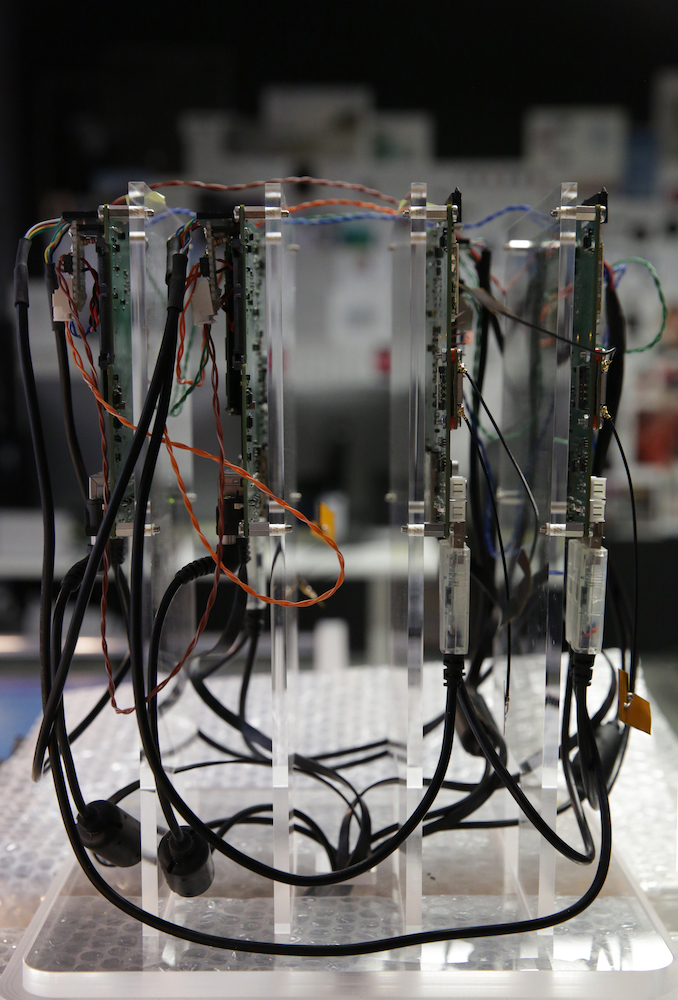

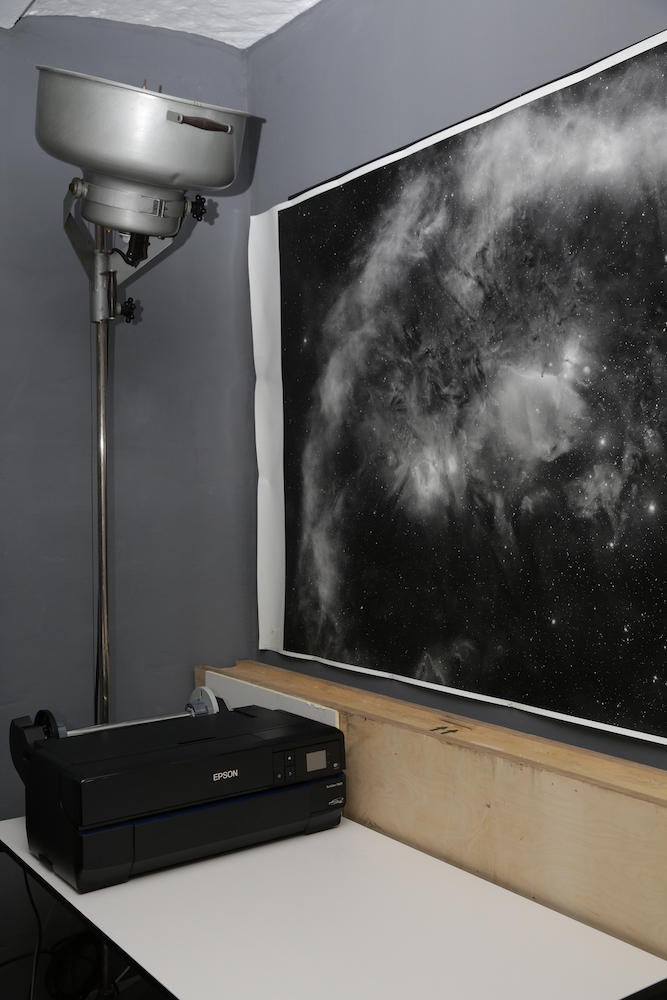

There are four desks in the production room on the ground floor. Three hold computers while the other is cluttered with various materials, such as a lightbox, cutting mats, scissors and glue, along with a partially deconstructed Autonomy Cube in need of repair. Metal shelving units are stacked high with transparent plastic boxes holding everything from external hard drives, power strips and cables to 35mm lenses, GoPros, webcams, and LED tools. One wall is covered in a webbed network of research and reference images, while another hosts a large-scale print of a work-in-progress, part of a new project that will be unveiled in May at Pace gallery in New York.

Among the wall of references are small images of undersea cables, phrenology diagrams, and portraits commonly used in AI training sets. Each of these clusters allude to photographic series that were previously exhibited. Although he is not actively producing anything in relation to these at the moment, their continued presence is indicative of Paglen’s overarching workflow: “I’m never like, ‘Here’s the series, these are the dates, and now it’s done’,” he says. “Projects are always ongoing.”