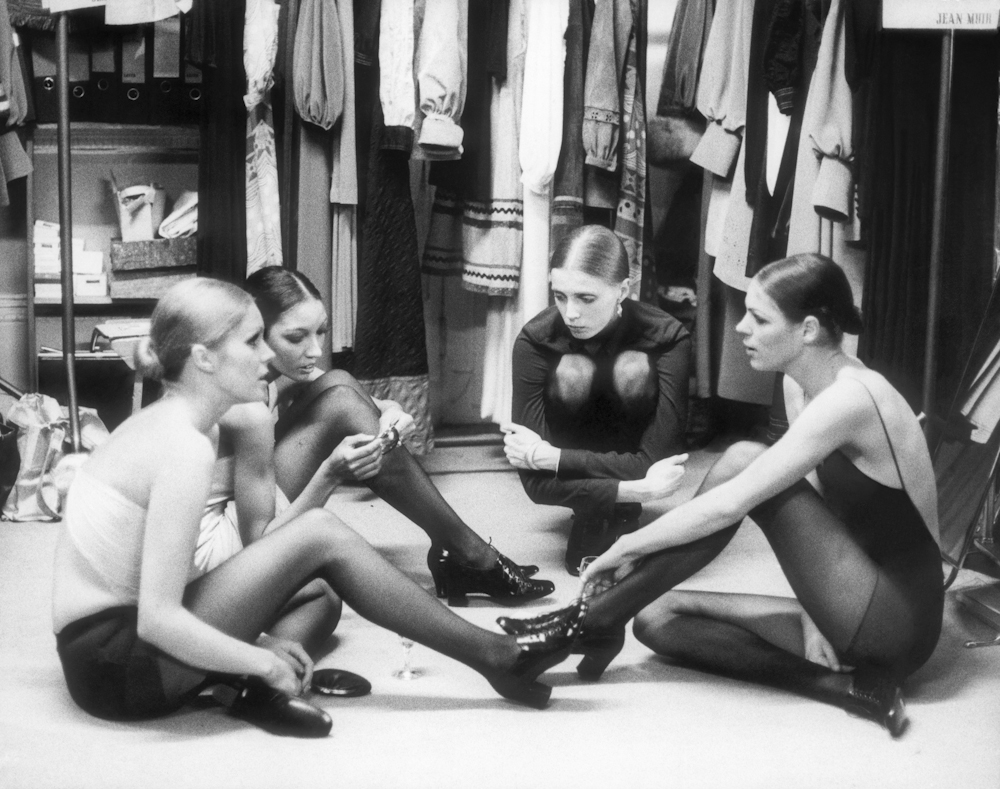

Joanna Lumley with models backstage during Jean Muir fashion show. All images © Marilyn Stafford

Curator Julia Winckler looks back at the photographer’s extraordinary life and work following her death earlier this year

The professional career of pioneering photographer Marilyn Stafford (1925–2023) began in New York in 1948. She had moved there hoping to become an actress on Broadway. One day, friends at the Screen Actors Guild gave her an old Rolleiflex camera and encouraged her to take up photography. As a result, she was asked to accompany them for an interview with Albert Einstein to take his portrait. At the age of 23, and with limited photographic experience, Stafford’s first commissioned portrait was of the world’s most famous physicist, whose relaxed and inquisitive gaze she captured so wonderfully and instinctively.

Stafford, who died in January at the age of 97, leaves behind an extraordinary collection of photographs and an extensive archive spanning four decades, reflecting her dedication to social reportage, street photography, fashion and portraiture. I had the pleasure of knowing Stafford personally, and interviewed her on multiple occasions: in 2017, when I curated an exhibition of her early Paris photographs at Toronto’s Pierre Léon Gallery, and in 2020, when I organised an online international photographic symposium at the Sorbonne, Paris, to mark her 95th birthday. Throughout her long photography career, Stafford sought to engage her visual creativity and intuition. As she explained to me in 2016: “I liked to allow things to flow with feeling rather than mechanically.”

Stafford grew up in a secular Jewish family during the 1930s in Cleveland, Ohio, where she performed at the Cleveland Play House before attending drama classes at the University of Wisconsin. Her family’s origins were rooted in Eastern Europe, and her deep affinity for migrants, displaced people and communities living on the margins of society stretched back to childhood. Growing up during America’s Great Depression, she witnessed first-hand people being forced out of their homes.

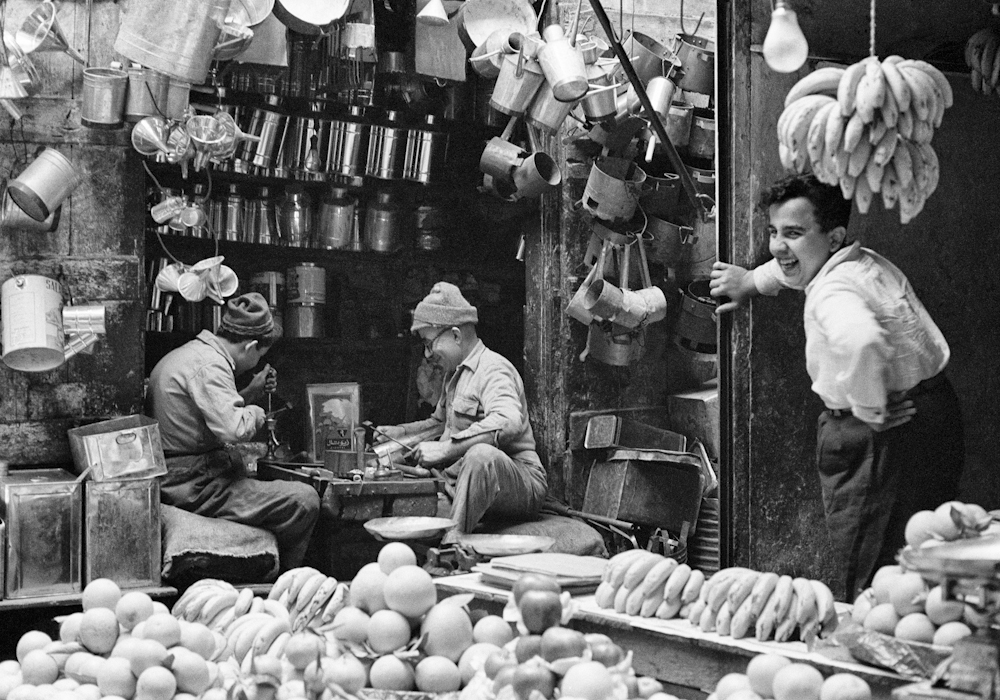

She was deeply moved and influenced by images made by Dorothea Lange and other photographers commissioned by the Farm Security Administration of destitute sharecroppers and farm labourers. In December 1948, aged 23, Stafford accompanied a friend to Paris and instantly fell in love with France. She moved to the French capital the following year and for a while performed as a singer at Chez Carrère, near the Champs-Élysées, where she met Édith Piaf and became friends with Robert Capa. Encouraged by Capa, she took her Rolleiflex and discovered the city by bus, immersing herself in her new life. She had a couple of jobs assisting and studying with studio photographers, but much preferred to go out and make street photographs.

In doing so, she joined an already established tradition of urban street photography in Paris, which stretched back to Eugène Atget’s pioneering photographs of the city at the start of the 20th century, a time when it was undergoing large-scale transformation. Unlike some of her contemporaries, Stafford never posed any documentary street scenes. Instead, she tried to capture spontaneous moments.

“Although the fashion work meant I could earn a living, I would have rather spent more time taking photographs that were more relevant to humanitarian issues and social justice”

Between 1949 and the mid-1950s, Stafford made candid street portraits in various Parisian neighbourhoods, including Boulogne-Billancourt and in the Cité Lesage-Bullourde, where she photographed children playing in its narrow streets. Despite the children’s harsh living conditions, Stafford’s great empathy with them is palpable, as are the youngsters’ playful interactions with the photographer. Stafford felt at ease on the street, she said, during our interview for the catalogue of her 2020 exhibition, Les Enfants de la Cité, that I curated. It was not long after the Second World War, and there were very few photographers – let alone women photographers – wandering about the streets making photographs.

In 1955, Stafford was introduced to Henri Cartier-Bresson by Indian writer Mulk Raj Anand. The famed photographer became Stafford’s friend and mentor, and she accompanied him on many of his urban photography walks. She recalled sitting with him in a café one day: “He had the camera at his waist and he just saw a picture and he clicked it; he didn’t even put the camera to his eye. He knew how to operate that Leica so well.”

Cartier-Bresson always tried to blend into the background, and through him Stafford learned to wear totally unobtrusive clothing. “He always wore a raincoat and a hat. I took the habit of understating whenever I went out to take photographs. It became a pattern in my life. Even though I later worked for years in the fashion industry, I always wore something very nondescript to not stand out.” Working in fashion, Stafford took models into the streets, and was one of the first photographers to merge street and fashion photography.

In a recorded interview from 2020, Stafford said: “Bringing the life of the streets into it was part of who I was. Although the fashion work meant I could earn a living, I would have rather spent more time taking photographs that were more relevant to humanitarian issues and social justice. I wanted to do photojournalism, not studio work.” The photographer married the British foreign correspondent Robin Stafford in 1956.

Two years later, already pregnant with their daughter Lina, she undertook an arduous journey across Tunisia to document the plight of Algerian refugee families, who had sought sanctuary across the border in makeshift camps. This included photographs of mothers comforting their small children and of young children on their own in small groups. The Observer used two of Stafford’s photographs on its front page in late March 1958. It was the first time her photographs appeared on the cover of a national newspaper, and they galvanised a large public response, prompting investigations into the crisis in the UK.

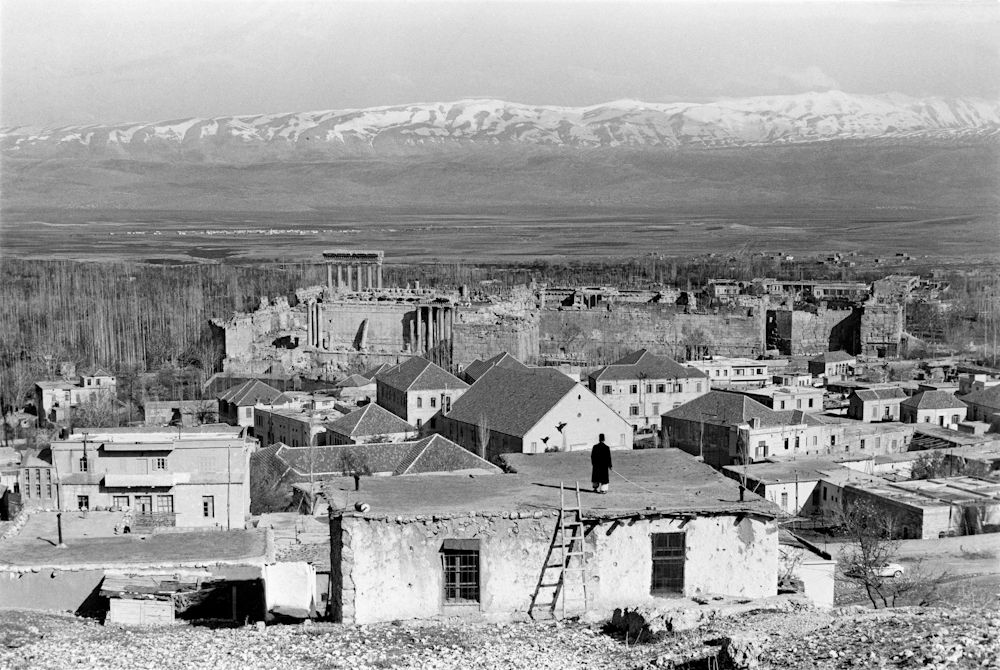

In 1959, the young family moved to Rome, where Stafford continued her portraiture work, photographing artists and writers, including Italo Calvino and also Francesca Serio, a hugely courageous Sicilian mother who brought the Mafia to trial for murdering her son. By 1960, the Staffords lived in Lebanon and Marilyn travelled across the country to make documentary photographs in remote rural areas of life in traditional villages. Encountering a country at the crossroads of tradition and modernity, with women’s emancipation growing, she documented city life and modern Beirut.

Over three decades later, in 1998, the photographs were published by Saqi Books as Silent Stories: A Photographic Journey through Lebanon in the Sixties. Following a stint in New York, the Staffords separated, and in 1964, Marilyn and her daughter Lina moved to London, where the photographer would work for Vogue, Women’s Wear Daily, Chicago Tribune, BBC and other international organisations.

She was one of very few women photographers working in Fleet Street and made a name for herself as a fashion photographer of haute couture and ready-to-wear clothes, capturing London models and personalities at the height of the Swinging 60s. She was at the heart of the fashion world, taking portraits of Twiggy and Joanna Lumley.

Throughout, she continued to focus on social issues. In 1972, she photographed May Hobbs, a mother of five and a lead organiser for London night cleaners. Together with other cleaners and members of the Women’s Liberation Movement, they formed the Cleaners’ Action Group. Stafford’s image was used for The New York Times and the International Herald Tribune, illustrating a story of struggle for better pay and job security. Stafford’s commitment to investigatory, feminist documentary photography is also exemplified by several significant reportage projects. In late 1971, she travelled across India for a month with Indira Gandhi, the country’s first and only female prime minister.

The following year, she documented the aftermath of the Bangladesh Liberation War, covering the experiences of rape victims who had been shunned and abandoned by their families and communities. The photographs were published by The Guardian and the stories raised substantial funds in support of an Indian women’s refuge. In her mid-fifties, Stafford retired from professional photography and her work remained largely unknown until she was in her nineties.

At the age of 96, Stafford held her first retrospective, A Life in Photography, at Brighton Museum & Art Gallery last year. Curated by Nina Emett, in collaboration with Stafford’s daughter, Lina Clerke, the exhibition was accompanied by a monograph published by Bluecoat Press. At the exhibition opening, Stafford held an appreciative audience captive, sharing the stories behind her images. Her deep commitment to social documentary photography remained unshaken, as did her life-long belief in its power to generate empathy and spur people to action.