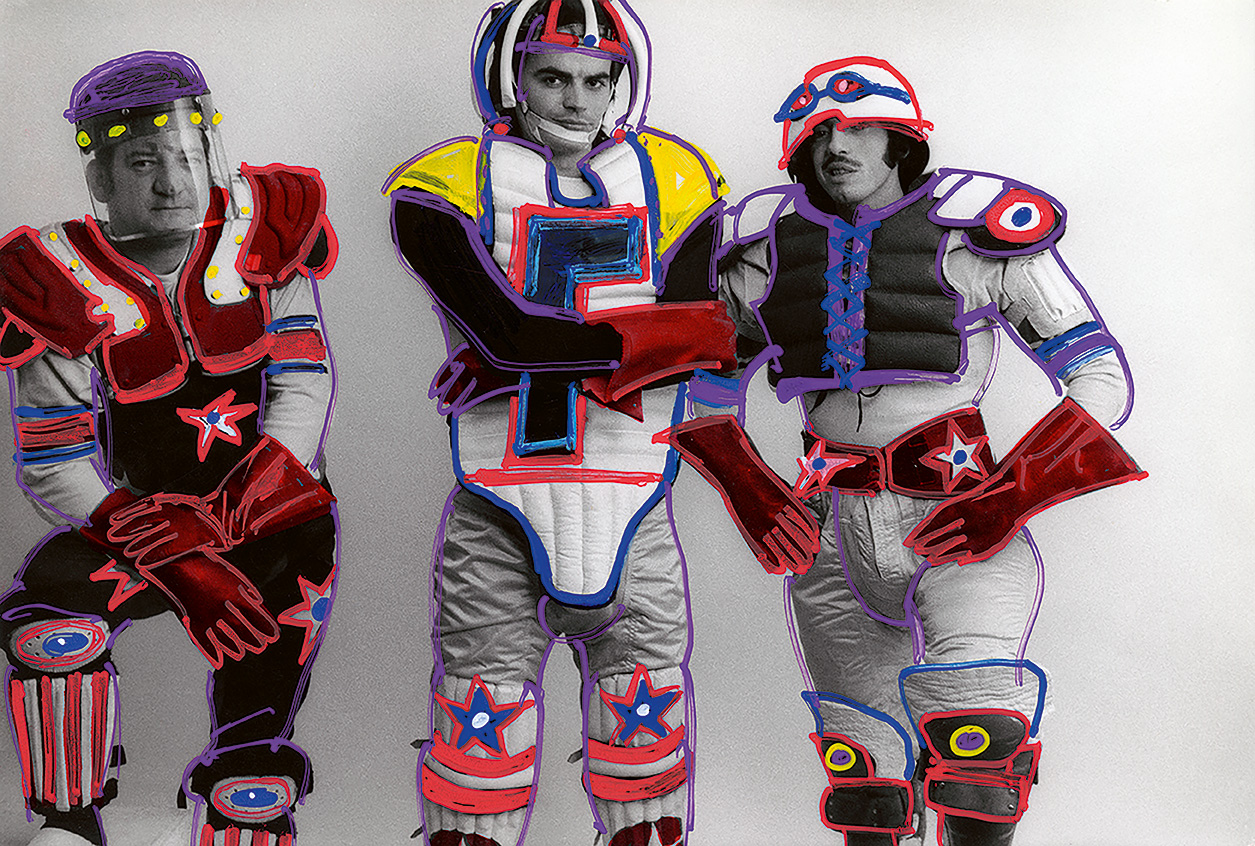

William Klein, Op-art dressing room and models, 1966

As the definitive book of the late photographer’s career lands, collaborator and ICP curator David Campany reflects on Klein’s polymathic genius

William Klein died in early September at the age of 96, just as the major retrospective of his work that I had curated for the International Center of Photography (ICP), in New York, was closing. There are very few who have had a creative life as rich, restless, original and influential as Klein’s. He seemed to enjoy several careers at once: abstract artist; designer; painter; street photographer; fashion photographer; documentary film- maker; fiction film-maker; book-maker; writer.

The multi-hyphenated life in art is commonplace today, but Klein pioneered it. It was natural to him. It perplexed people, of course, especially museum curators who, for decades, could not quite get their heads around such omnidirectional brilliance. This bothered Klein – but not too much. Most of his work was made for the pages of books and magazines or the big screen, not the gallery wall.

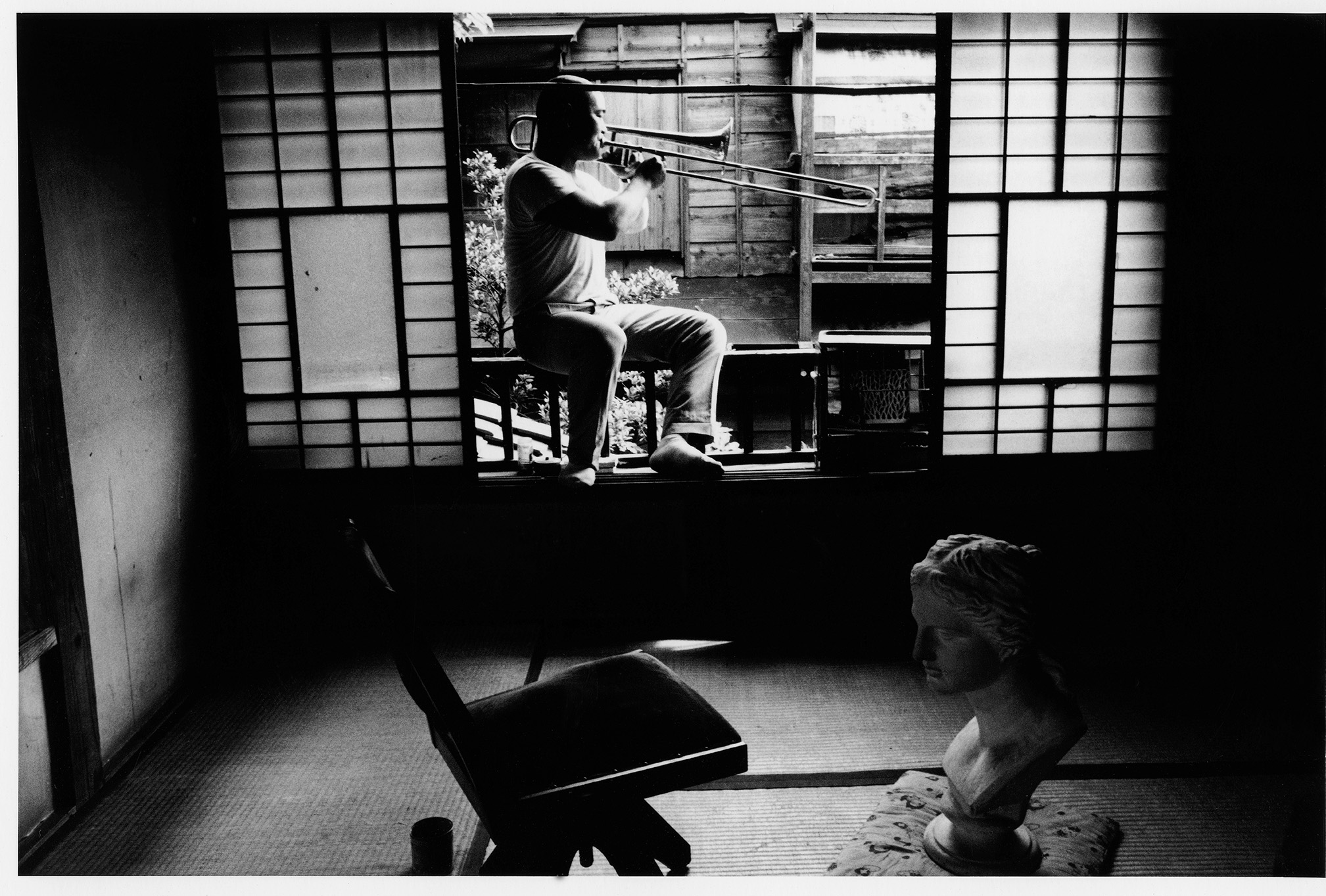

Perhaps even more impressive than the range of Klein’s practice was its longevity. He made consistently exceptional work for well over 60 years. It was all one artistic adventure, informed and shaped by an enormous appetite for life and a curiosity about all people. New York, Paris, Milan, Rome, Senegal, Algiers, London, Scotland, Tokyo, Moscow, Turin – he reached out everywhere, talked with people, got to know strangers and invited them into the spontaneous game of making a photo or a shot for a film.

Young street kids acted like movie stars or gangsters. Fashion models brought their personalities and poses. All were welcome in the Klein frame. They gifted their energy and humanity; and Klein brought his timing and astonishing flair for complex composition. A wide lens meant he had to be up close to fill the frame, not hanging back, invisible. There is a deep ethic in this kind of interaction, and it chimes with image-makers today who grapple with the often-awkward power relations of the camera. Klein was simply upfront about what was happening – and you could see it.

At ICP, we were all deeply saddened by the news of his death but not altogether shocked. Klein had not attended the opening of his exhibition in June, making this the first show of his work that he was not able to visit. It was bittersweet in more ways than one. He was born in New York in 1926, left for Europe in 1946, and lived most of his life based in Paris. The show was his artistic homecoming, in ICP’s building on the Lower East Side, just around the corner from the clothing store his Hungarian immigrant grandparents had set up on Delancey Street. Years later Klein made some of his grittiest and most energetic street photos here, as well as some of his most playful fashion images.

It is almost beyond belief that his New York street pictures of 1954–55 were his very first attempt to photograph the outside world. Before that he had only made abstract photograms in his darkroom. But Klein and his camera were so hungry they seemed to swallow the city whole. The screaming commerce, the racial tensions, the bravado and bullshit, the tenderness and fragility. The 1956 book of those photographs, New York – shot, edited, designed and written by Klein – could well be the most influential photobook ever published. From there on, his pace was breathless, producing more city books, conquering fashion photography, and making documentary and fiction films.

I could have put together a show just about Klein in 1964. In that year alone, he was at the top of his game at Vogue; he published his third and fourth photobooks (Moscow and Tokyo); he was still painting in his studio; and was in Miami to shoot the first documentary about the boxer Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali). That movie is electrifying, with Clay and Klein both spontaneous and sparring joyously with each other. It screened all over the world, most notably in Africa, where it made the boxer an icon not just of sport but of a confident Black consciousness.

“Although he was at the centre of so much, Klein never fully belonged, and he liked it that way”

In 1969, when the city of Algiers hosted a Pan-African festival, inviting Black politicians, poets, performers, artists and activists from around the world, it was Klein who got the gig to make a film of it. While there he also met Eldridge Cleaver, a spokesman for the Black Panthers. Klein made a portrait film of him, and half the profits from screenings in America went to the Panthers. There were movies about Little Richard, Hollywood, consumerism, America’s ‘military-entertainment complex’, the political upheavals of May 1968, the Vietnam War, and more.

Although he was at the centre of so much, Klein never fully belonged, and he liked it that way. He was the remarkable fashion photographer who also made Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966), a deeply satirical feature film about the fashion world. He reinvented documentary photography without really caring what documentary photography was. He was on the fringes of all the key movements in 20th century culture, from Pop and Situationism to Cinema Verité and the French New Wave, but he never fitted into any of them. All rules could be broken or just ignored.

Klein worked at such a pace that he was over three decades into his career before he ever looked back. In the 1980s, French TV commissioned Contacts, a short film in which he discusses his process by examining his own contact sheets. Why was this frame chosen for publication and not another? How did a situation evolve from shot to shot in a sequence?

This film, coupled with the fact that the world was finally catching up with his achievements, led Klein back to galleries and museums, making grand survey shows and smaller exhibitions focused on single projects. These exhibitions and accompanying books consolidated his status while he pushed on with new work: an extraordinary film based on Handel’s Messiah (1999); more fashion; a book about the cultural and political tensions in his home city of Paris; a return to photographing New York.

There are still untold depths to discover in William Klein’s archive, whole bodies of work that have barely been seen. Of course, when an artist dies there is a rush to define their work, but in Klein’s case we ought to resist that. I suspect it will be a while before the full extent of his vision is known.

William Klein: Yes by William Klein, with an essay by David Campany, is out now (Thames & Hudson)