Inspired by the work of her grandfather, Wilson retraces his footsteps through Texan deserts in a journey of both emotional and evolutionary discovery

“I knew my grandfather as your typical grandpa – but he was an educator, he was in academia, he wasn’t always the warmest and cuddliest version of a grandpa,” says Sarah Wilson. “He would come to my show and tell classes in elementary school and bring these amazing, huge fossils. I think the kids thought it was pretty cool; I definitely thought it was.”

At times, Wilson becomes emotional as she recalls her grandfather. It’s clear that the professor of geology and palaeontology had, and continues to have, a meaningful impact on her – both as a beloved family member and as a source of photographic inspiration.

Before he died, Wilson’s grandfather left her three black metal boxes filled with faded Kodachromes – images of rock formations, bone fragments and landscapes, taken during his annual digs in West Texas and Big Bend National Park. Holding them up to the light, Wilson realised that she and her grandfather had photographed some of the exact same desert landscapes, from the same vantage points, only 50 years apart. This shared connection ignited an adventure and a long-term project, featured in the pages of her first book, DIG: Notes on Field and Family.

“It basically started this whole journey, where I now go on palaeontology digs every winter and join these palaeontologists who are looking for some of the same bones my grandfather was,” Wilson explains. But these digs, and the work Wilson creates while on them, are not merely scientific, and their meaning is not tied only to her own family.

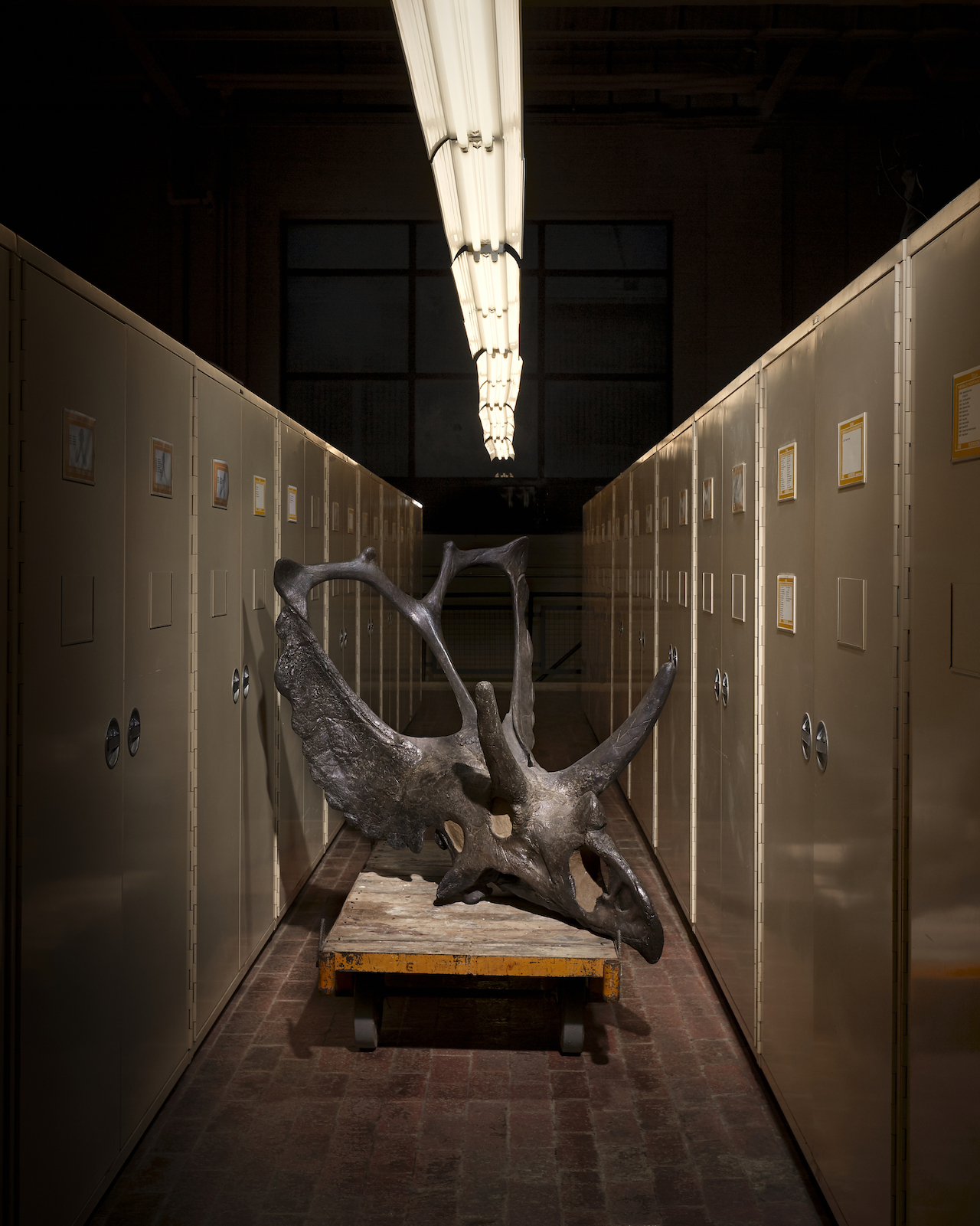

Wilson’s images of seemingly endless Texan deserts and long extinct creatures, alongside conceptual self-portraits in the style of geology and anatomy charts, speak to an origin story that reaches beyond traceable generations. Each bone collected is evidence of the slow, significant work of evolution, serving as a reminder that we, as humans, sit at the very end of that timeline.

All of this, Wilson explains, makes this work as much about our connection to the Earth, as about her own link to her grandfather. “It’s a sad reflection that we don’t take all of that time and perfect evolution into consideration with how we treat each other and our planet,” she says. “Millions of years from now, when some form of a palaeontologist can see the stratum of our dirt and our planet, what will our layer look like? To me, that’s hard to reckon with.”

The creation of DIG was also, in moments, hard to reckon with. It took Wilson some time to accept the work as a combination of the personal and the scientific; to allow herself to acknowledge that her story – and that of her grandfather – were worth telling. “It’s not only thinking about my connection with him over these years, but the connection that we all have altogether,” she explains. “As mammals, as humans, as a species, connecting to our ancestors – I didn’t really know what that magical feeling was, but it has really carried through this whole project.”

Sarah Wilson, DIG: Notes on Field and Family, is available to pre-order now (Yoffy).