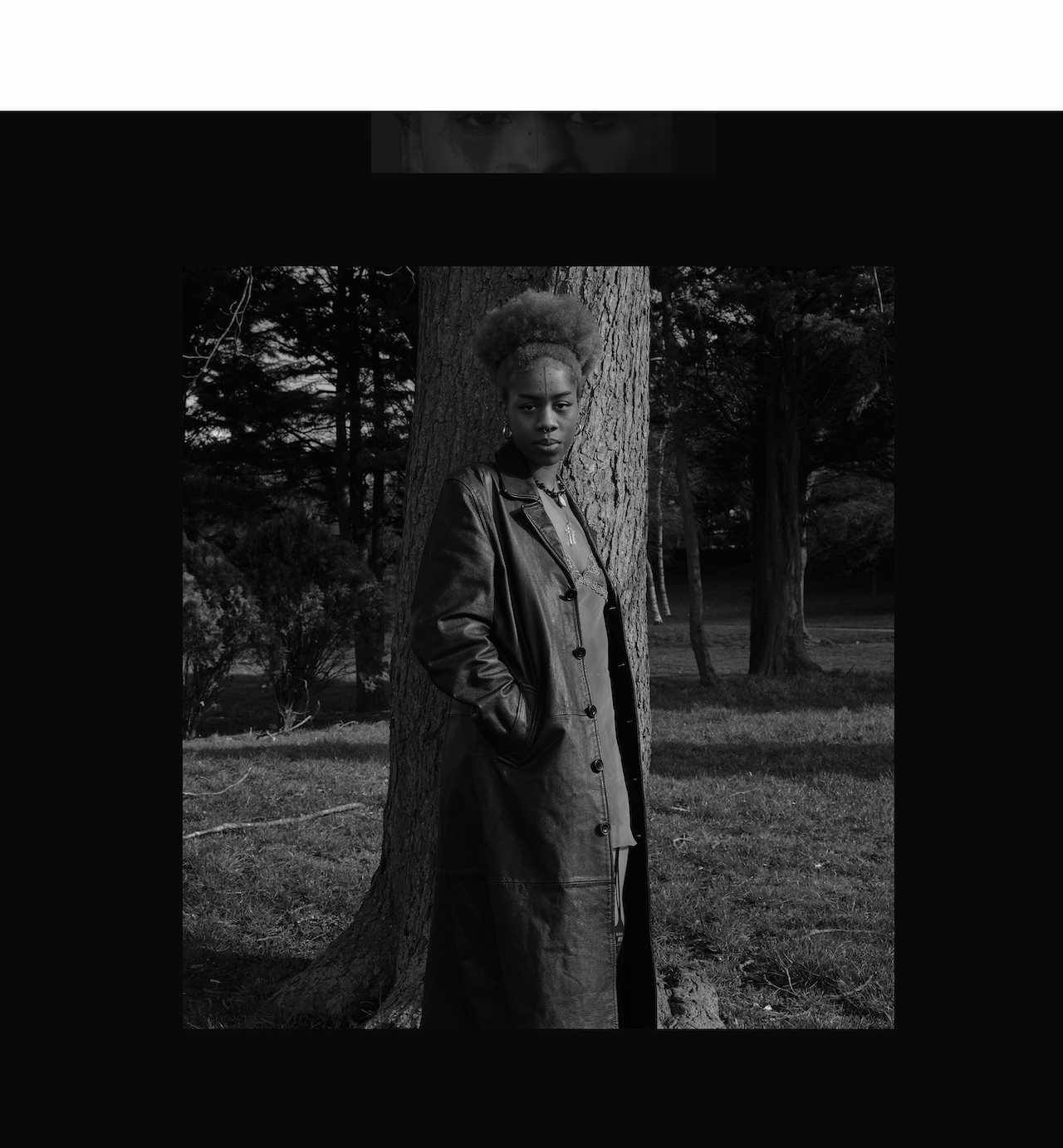

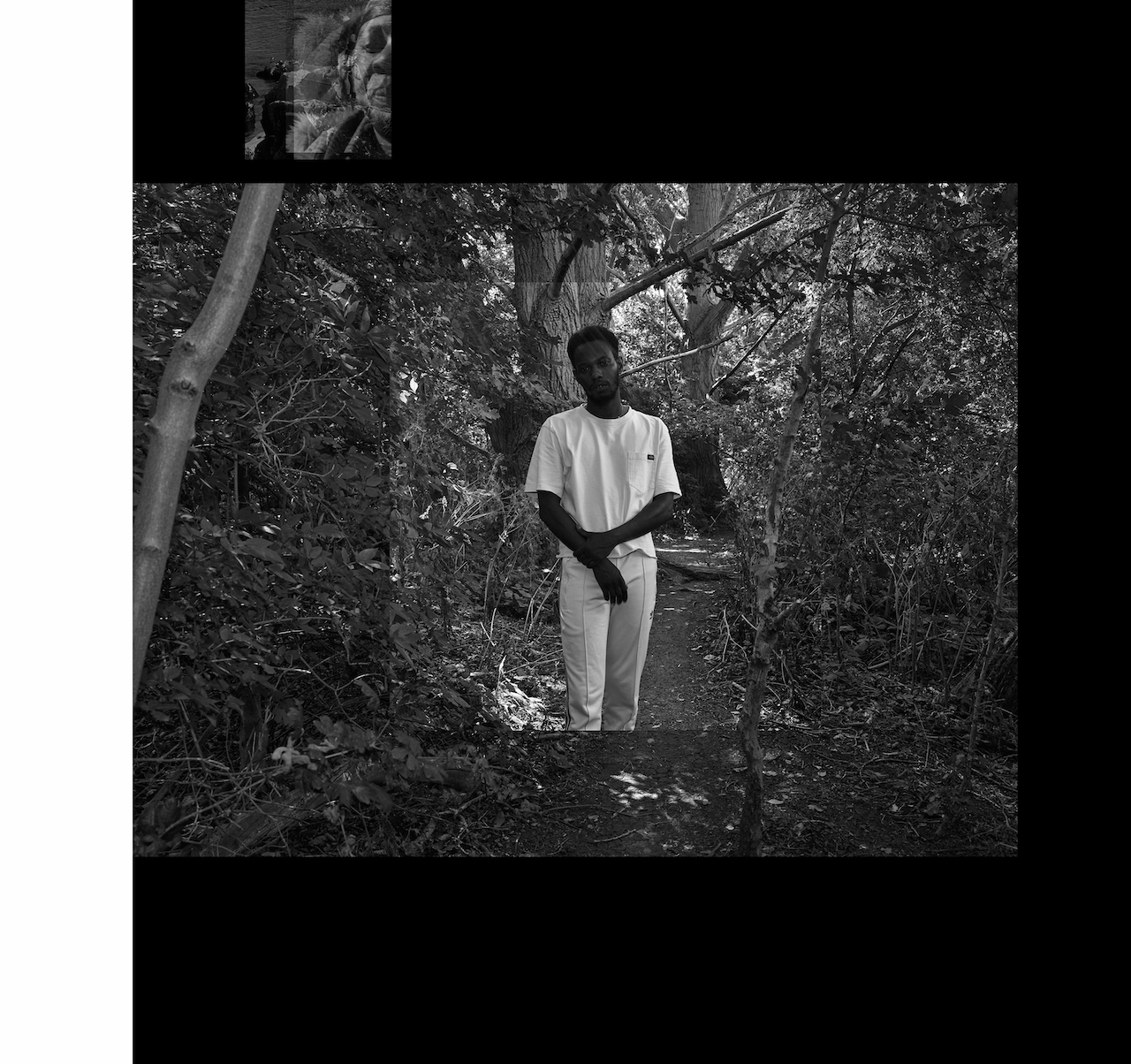

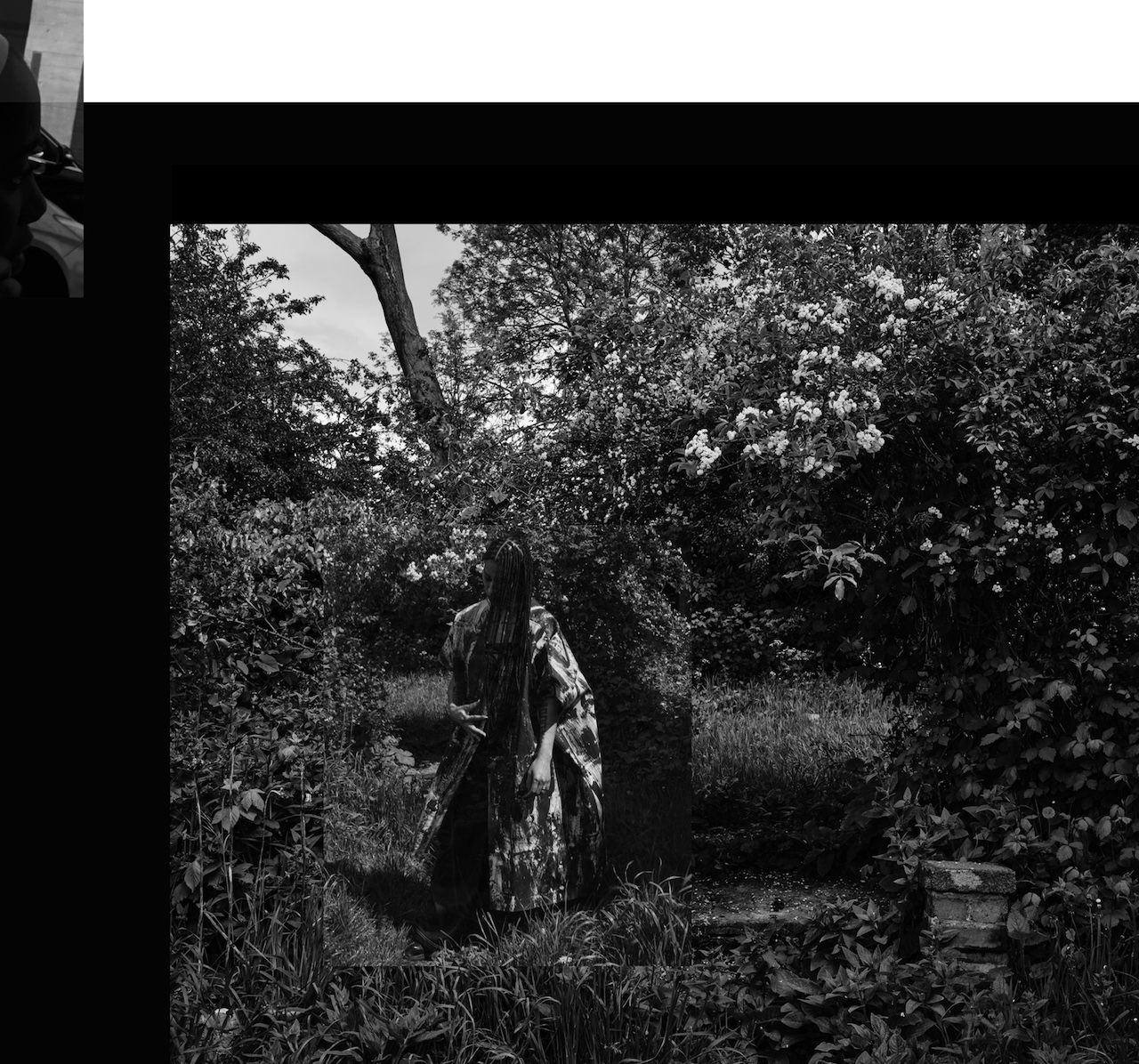

“I wanted to disrupt the viewing experience in a slightly ambiguous, obtuse way, to create figures like ghosts,” says Francis, whose ongoing work urges viewers to re-evaluate who is considered the natural inhabitant of English landscapes

Born in Birmingham, Jermaine Francis grew up in the 1980s in Tipton, a working-class, former industrial town in the West Midlands of England. He studied at Walsall Art College and Derby College (now University of Derby) then moved to London, where he has carved out a career in photography. He now works with organisations such as i-D, Beauty Papers, Self Service, Frieze Art Fair, Stella McCartney, and Marni, and has self-published two photobooks, Something that seems so familiar (2020) and Rhythms from the Metroplex (2021).

Fancis’ practice is rooted in documentary and portraiture, driven by personal experience and issues that arise out of interactions with the everyday environment. His ongoing series A Storied Ground – currently on show in Paris – employs montage to consider the absence of the Black figure in the English pictorial landscape.

In the following interview, the photographer discusses his roots, and the intention behind disrupting the landscape, and breaking down perceptions.

Where did you grow up, and what was it like?

I was born in Birmingham but grew up in a town nearby called Tipton. Tipton was known for its early coal mining and factories, but in the 1980s it was de-industrialising. Its demographic was mainly working class, white and south Asian, with a very small minority of Black, Afro-Caribbean families. The National Front and racism were extremely prominent politically and culturally in the West Midlands at the time, and racism was an everyday experience. But my close unit of friends wanted something different. We grew up embracing a mix of cultures.

How did you get into photography?

My mum loves taking photographs, so I was surrounded by them. In my family there was a large amount of vinyl records, especially reggae and soul, which always had interesting cover photography. But I got into art mainly because of my Auntie, who was an art teacher. My journey with photography began when I did my foundation at Walsall Art College. We had a lecturer called Jed Hoyland, who showed us how photography could be a device to investigate the space and time around us. Being Black and working class, it helped me try to understand and negotiate the world. I spoke to Ekow Eshun about this recently, and he pointed out that theory gives us, as Black people, a way of unpacking and tackling the system we live in.

“Historically the Black figure is absent in the English Landscape, which has a strong relationship to nationalism and colonialism. I wanted to consider the Black figure in the landscape, to show that we cannot just be, that these codes infiltrate and influence how the Black figure is seen”

Why did you decide to shoot your new series in black-and-white, and work with montage?

I wanted to play with a textural feel but also tones, inside and outside the images. I wanted these images to point to the codes in English pictorialism and landscape imagery, to the flattening and uniformity these codes create. I wanted to play with a certain seductiveness of the space – beauty is a part of the landscape, but I wanted to disrupt that.

I decided to make montages to physically disrupt that space for the viewer. Historically the Black figure is absent in the English landscape, which has a strong relationship to nationalism and colonialism. I wanted to consider the Black figure in the landscape, to show that we cannot just be, that these codes infiltrate and influence how the Black figure is seen. I wanted to disrupt the viewing experience in a slightly ambiguous, obtuse way, to create figures like ghosts that still exist in the space.

Who are the people you photographed?

Some are people I know, others I got to know through making the work. They would all class themselves as alternative, and have all found the natural or rural landscape important. These two things worked on many layers. Being Black and alternative isn’t new, but it is still met with prejudice. Being Black is still presented as some hegemonic position, its complexity, nuance, and richness flattened into one easily digestible identity. It’s a kind of reductionism which is employed on many groups.

The perception of Black people as immigrants plays into how we see ourselves, and how we are seen in these places. There are economic factors at work, but these perceptions are slowly being broken down by groups such as Flock Together, a bird-watching group for people of colour started by Ollie Olanipekun and Nadeem Perera, or Black Girls Hike founded by Rhiane Fatinikun. These groups are important, to show we belong in these places and break perceptions of us, inside and outside the community.

Have you come across Ingrid Pollard’s series Pastoral Interlude? It considers similar issues but it’s from 1988. Is it surprising, or shocking actually, that similar issues are still at hand?

Pastoral Interludes is one of the most important works I have seen, I can’t express how important it is to me. I discovered Ingrid’s work while I was studying at Derby. A lot of my fellow students were making work on the rural landscape, but I didn’t have the same affinity to the space as them. I appreciated it, I wanted to enjoy it, but there was something underlying that I could not properly articulate yet. My experience, like many Black people, was that I did not belong in this landscape. Then I saw Ingrid’s work, someone like me explaining why I had this apprehension, why I maybe had this tension. In many ways this has influenced my thinking about space, this interrogation of the Black figure in space.

I am not all shocked and surprised that these issues still exist, though I am also not surprised that others are. In recent years I think people have taken it for granted that things just progress in a certain way, that old ideologies disappear. But as we can now see in many cases, not just in regard to race, that is not the case. Progression is not a given.

A Storied Ground by Jermaine Francis is on show from 28 September – 28 November at Galeriepcp, 8 rue saint-claude, 75003 Paris.