As the country enters an uncertain political and social landscape once more, Peress’ 2,000-page document of Northern Irish life in the 1970s and 80s takes on a renewed significance

Time moves differently in the North of Ireland. Its capital heaves with the history of conflict. Walls are painted with murals that reflect both Loyalist and Republican proclamations, the pavements in opposing flag’s colours. Stormont – the Northern Ireland Assembly that was formed with the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, bringing an imperfect peace after decades of British occupation and civil unrest – sat in a state of decay after power-sharing collapsed in 2017. This set a global record for the longest peacetime period without a functioning government. Across those three years, vital legislation and policy on everything from abortion to electricity, domestic violence and climate action were halted. Local stories, memory, and gossip morph around the North’s fug of time, tension, and collective trauma.

“Somebody once said that the trouble with the English is that they never remember, and the trouble with the Irish is that they never forget,” John Hume, late leader of the Social Democratic Labour Party and an architect of the peace process, once said. As an Irish immigrant in London, I am still struck by the dislocation of the British State from its responsibility, and the lack of understanding, education, and collective reckoning with colonialism in the North by British society. It is apt then that now, 30 years later, photographer Gilles Peress’ documentation of the Troubles is presented at The Photographers’ Gallery in London.

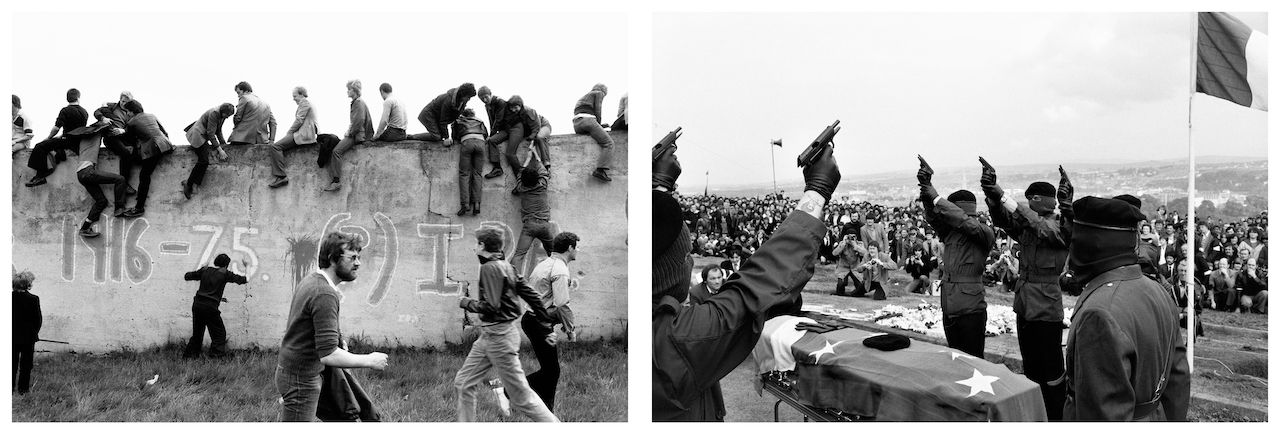

The exhibition is part of this year’s Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize exhibition. Peress was nominated for his photobook, Whatever You Say, Say Nothing (Steidl, 2021). It presents three decades of the French photographer’s work from multiple stretches of time spent in the North. Its three books are described as “documentary fiction”: two hefty photo albums, plus a companion almanac of contextual material, titled Annals of the North. Here there are descriptions of various characters of The Troubles: politicians, paramilitaries, activists, and local personalities – collated in a “cast” list, like a theatrical drama. At 2,000 pages, it is loosely structured around 22 semi-fictional “days” – “Day of Internment”, “Day of Struggle”, “Prison Days” – from the 1970s onwards. The work is contextualised by a glossary of place names, local colloquialisms, and mini-histories.

“The famous Northern reticence, the tight gag of place and times,” poet Seamus Heaney writes of the “wee six” North counties. “To be saved you only must save face / whatever you say, say nothing.” Language, Peress and I agree, is everything. At the beginning of our interview, he states assuredly that he calls the region ‘the North’, rather than ‘Northern Ireland’. Language is a cultural identifier, with a fraught history and a distinctly Irish power as both poetry and political battleground. The “whatever you say, say nothing” title is a mantra that also appears on a notorious IRA poster that warns local people against snitching. It features in the book alongside other posters, murals, and materials that build a capacious tapestry of life amid war.

When Peress and I speak over Zoom, language is something we come back to interrogate throughout our two hour conversation – what does ‘peace’ mean to you? Faith? When we speak too, it’s the day of the North’s election results – for the first time, nationalist party Sinn Fein has won a majority. It is heralded as a new era. A historic election. I describe it as monumental, surreal. I am used to the same outcomes and stagnation. “We used to say ‘not in my lifetime’. Now, maybe in my lifetime?” he says. “Still, I won’t have us hold our breath. We have much to discuss.”

“Ireland was one of Britain’s first colonial experiments. It is a manual for imperialism. This was what really motivated me with this book. To test the limits of time, vision, and narrative, in the face of what a state says to be true”

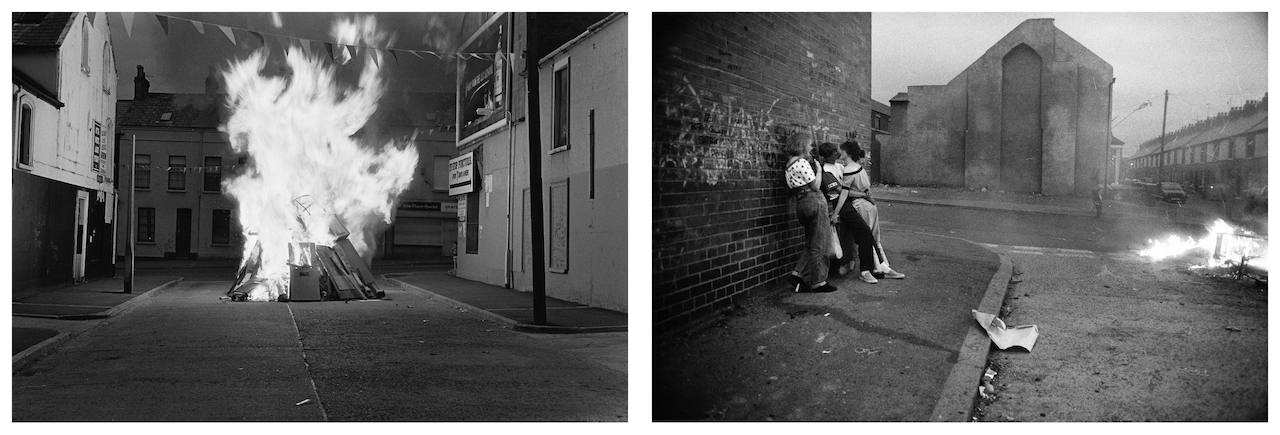

The region’s structures and rituals inspire the book’s spiralling narrative – the imposing Loyalist marching season across Spring and Summer, political peace-making milestones, commemorations for dead hunger strikers. “Time is not linear in the North. It is not in any conflict I have photographed, like Palestine. I wanted to show that recursive structure,” says Peress. “Today is tomorrow, tomorrow is yesterday, or 10 years ago.”

Peress has spent an expansive career photographing life amid conflict, revolution, and genocide: in Palestine, Rwanda, The Balkans, and Iran, with seminal photobooks and shows including The Graves: Srebrenica and Vukovar, The Silence: Rwanda, Farewell to Bosnia, and Telex Iran. He has honed a focused, immediate, and humane eye that expands the flattening of people and places experiencing conflict.

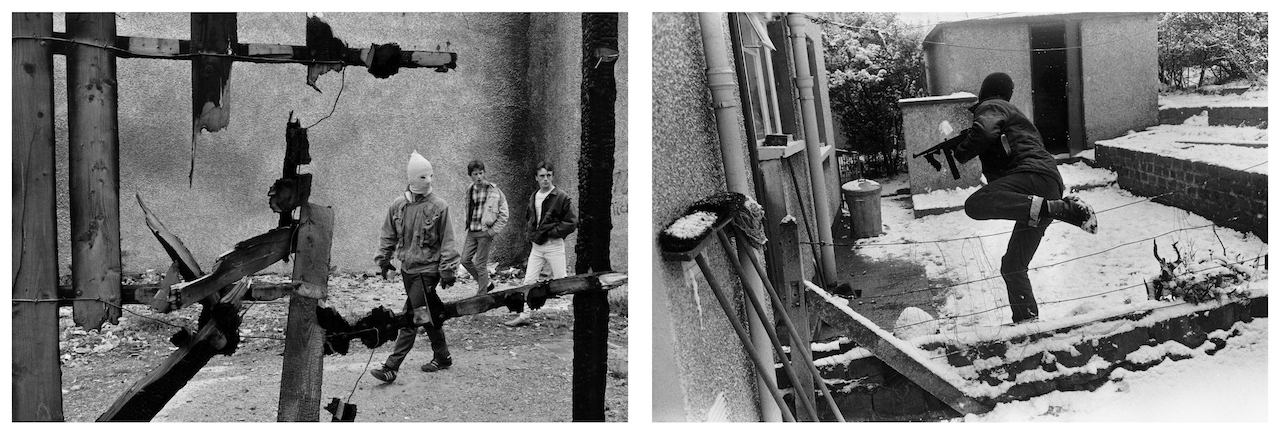

Far from voyeuristic or reductive, Peress’ eye feels inquisitive and nuanced. It’s clear how deeply he embeds himself and takes interest in the communities he documents. In the book indeed, he references a friend who he found out years later was a British government informant. His subjects retain agency: amid the throng of protesters, a young mohawk-sporting punk peering into his lens.

“Ireland was one of Britain’s first colonial experiments. It is a manual for imperialism. This was what really motivated me with this book,” he says, “to test the limits of time, vision, and narrative, in the face of what a state says to be true.

“The book is about the human condition and existence in a place which is highly ritualised by its never-ending conflict. The book was essentially done in the 80s. I returned to it in the 90s – the same amount of chapters and pages. My relationship to it has expanded. I was there for internment, for Bloody Sunday, the hunger strikes. And I was there in the Short Strand for the parties for people coming out of prison 15 years later for murder.”

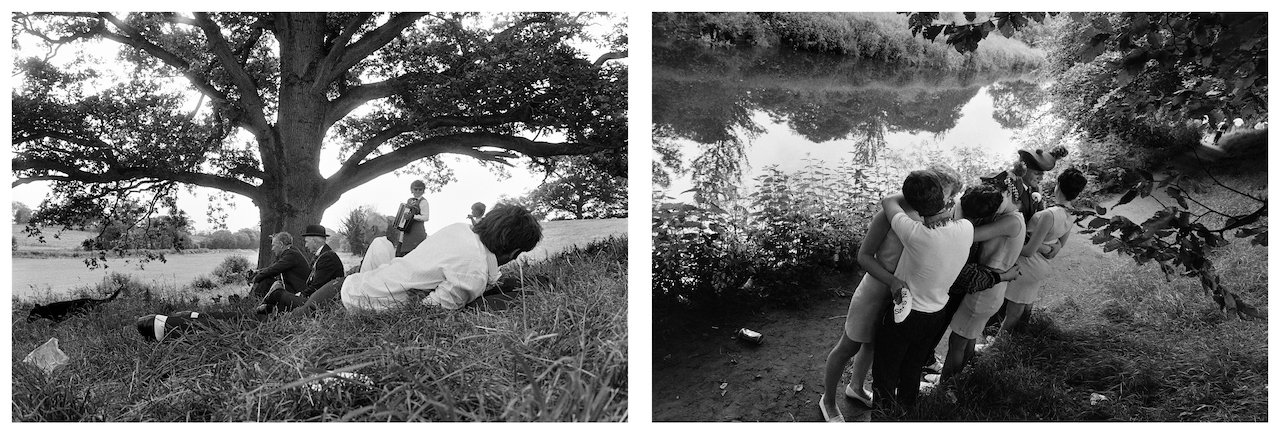

Amid the sprawling picture of conflict and war, Peress captures the variousness of people. We see Orange Order men carrying on and laughing, teenagers snogging close to army checkpoints, drinking in bars and gardening inner-city alleys, cheeky children goading soldiers. Sinn Fein’s Gerry Adams romps on a bouncy castle. “I had to be extremely emotional and rational at the same time,” he says.

“Every camera is both alive and deadly, it is a deep voice,” he continues, “but I don’t have a great sense of being an author here. I think there is a death of the author here, or a multiplicity of authors, and that’s important.”

As a young Frenchman, Peress was able to move across community boundaries and capture an expanse of identities beyond the tribalist stereotypes applied to the North of Ireland. Peress delves into the layers of exigencies to life here. Days blur and judder with violence, riots, marching, trips to the dole office and discos, of mourning and craic. He resists the grim or anaesthetising unrealities that much of outsider media has focused on. “I always work from the inside out,” he says, “the convergence of culture is conflict. It is state and religion deeply entwined. I found life and lessons in the people I met and the friends I made.”

Now, aged 74, Peress is most interested in “gathering evidence for history”, rather than creating “good photography”. Peress was 26 when he arrived in Ulster on one of many trips as a Magnum photographer. In 1972, he photographed the British Army’s senseless massacre of 13 innocent civilians and peaceful protesters in a civil rights march on Bloody Sunday. His images of the slain were broadcast around the globe. Bloody handkerchiefs. Approaching armed soldiers. Men, women, children, running for their lives.

“I remember shooting and crying at the same time, when I saw Barney McGuigan lying dead,” he says. He photographs Jim Wray, sat down in defiant, peaceful protest in the street. Minutes later, he would be shot dead in Glenfada Park. Peress’ court testimony transcript from the Saville Inquiry (2010), which ruled that the killings were unlawful after over a decade of deliberation, appears in the book. David Cameron officially apologised for the British action that year. In 2019, the Queen’s Speech would describe such pursuit of justice and legacy issues as “vexatious”.

History is being re-written, language loaded as a gun. Peress’ photography is a visceral challenge to that. He interrogates the limits and liberations of visual language in capturing such a complicated conflict, and the perception of understanding it as protracted and intractable.

“In Susan Sontag’s Regarding The Pain of Others, she describes being 14-years-old and seeing images of the Holocaust for the first time. She sees life as a before and after, that moment of witnessing the camps,” Peress says. Sontag reflects on the spectacle of suffering: the ethical, emotional, and moral value of photographing atrocity. Impartiality is not just impossible, it’s reductive.

“There is no objective truth,” Peress says. “Media – especially American and British media – is arrogant enough to believe differently. I want to make an image that functions as an open text. It is democratic. The reader has agency to read within the implied visual language.”

Today, Peress is a professor of human rights and photography at Bard College in New York, and senior research fellow at the Human Rights Centre at University of California, Berkeley. “I have begun to think more about visual language again with my students. We look at the culture of indifference and apathy in society, and how visuals play into this. I think about visual grammar, and how that is taught,” he says.

Sifting through pages and pages of Peress’ work, the weight of cyclical time and trauma, passed from generation to generation, weighs heavy. His images hopscotch raw and tender moments, transcending time. Though the ambition to capture such nebulous things is worthy, this exhibition and book feel more pertinent than ever.

The North is entering a new, uncertain political and social landscape once more. “I think the concept of peace is a smokescreen. It is not this static thing,” he says. “It is not something that can be dealt with and put in a box here, or Palestine. The state banks on fear and a lack of imagination to see life and structures outside of colonialism. There is no adequate representation of reality, and that is what I have to reach for. It is about refusing to accept the narrative.”

Whatever You Say, Say Nothing by Gilles Peress is published by Steidl. An exhibition of the work is on show at The Photographers’ Gallery until 12 June 2022.