Throughout history, the nude has transitioned from a figure of anatomical intrigue to a token of beauty, and even a political tool. From Weston to Mapplethorpe and into the present day, Joseph Glover unravels the then and now of the photographic nude

The photographic nude has been a driving force in shaping the relationship we have between ourselves and our corporeal understanding. From anatomical photographs of the pre-modernist era, to modern day explorations of sexuality and identity, the nude has consistently enabled artists to challenge preconceptions of what the human body is, and how we view it.

Edward Weston’s Nudes, made between 1920 and 1945, is a collection of photographs illustrating the strive of modernist photographers. It is a radical shift from pictorial or academic representation (common to photography before the First World War) towards an approach concerned with aestheticised form. Often singular and impersonal, Weston’s photographs are evidence of the beauty of the human figure.

Weston’s nudes sit apart from those of his contemporaries’. His unique interpretation of form and his masterful recognition of light and shadow render images that are unmistakably his own. In looking, we are often left no room for the comprehension of anything other than the rhythmic shapes which dance together to fill the photographic frame. It is an oeuvre of a dedicated photographer, one who saw “life as a coherent whole,” as he once wrote, in his Daybook of 1930. “And myself as a part, with rocks, trees, bones, cabbages, smokestacks, torsos, all interrelated, interdependent.”

In the same decade that Nudes was published, there was another drastic shift in the representation of the body. Through the 1970s and 80s, Robert Mapplethorpe’s transgressive photographs lifted the veil on sexual taboos of the time – fetishism, homosexuality and sadomasochism, for example. Unlike modernist photographers before him, Mapplethorpe’s vision of nude photography was political. Yet, although his subject matter was different, the intent was similar to that of Weston’s. “I am looking for perfection in form. I do that with portraits. I do it with cocks. I do it with flowers,” he said, in the catalogue of a 1996 touring exhibition, Mapplethorpe.

“How is the nude depicted in today’s culture? And how have our photographic depictions and representations of the nude shaped our present-day perceptions of race, gender, sexuality and religion?”

The radical picturing of the nude by modernist photographers like Weston heralded a shift in our perception of the body. No longer was it solely a piece of anatomical intrigue, but something more, something beautiful, something to celebrate. But how is the nude depicted in today’s culture?

Identity politics are now at the forefront of our political discourse. How we see the nude has been undeniably influenced by visual culture; we are taught how and what to see, in turn, telling us who and what we are. This year, John Berger’s iconic Ways of Seeing turns 50, and an increasing number of contemporary artists are examining the potential of the nude – exemplified in Fotografiska’s recent exhibition in New York, for example.

How have depictions of the nude throughout history shaped our contemporary perceptions of the body today? One way to better navigate the murky waters of our future comes from rereading the past. Considering the history of photography in a contemporary setting, we are able to learn about both the positive and negative impacts it has had on society. For instance, Weston’s depictions of the human form were from an inherently modernist perspective. But, in a contemporary analysis of the photographs, it is hard to dismiss the male gaze that punctuates each image. Has Weston’s framing of the model helped shape the current undertones of how we picture women and their bodies? And has his own personal romantic history – secret affairs with his sitters – contributed to the institutional maltreatment of photographic models?

Similarly, Mapplethorpe challenged our preconceptions of sexuality, but when re-viewing his fetishisation of nude Black men, we are witnessing the white ideal – an imagination of what Mapplethorpe sees, or wants, a Black man to be. Mapplethorpe saw his own nudes of Black men as racist: “It has to be racist. I’m white and they are black,” he once said. Still, the photographer’s inability to understand the racially ingrained power dynamic, and how he benefits from it, is apparent. “There is a difference somehow, but it doesn’t have to be negative. Is there any difference to approaching a black man who doesn’t have any clothes on and a white man who doesn’t have clothes on? Not really.” Again, How have these processes of thought and practice transpired into our culture today?

Weston and Mapplethorpe are only two small droplets in the wider notion of our photographic history, but they are examples that we must revisit in relation to society today. One hundred years since Weston marked a shift between pictorial and modernist nude photography, the evolution of the medium is ongoing.

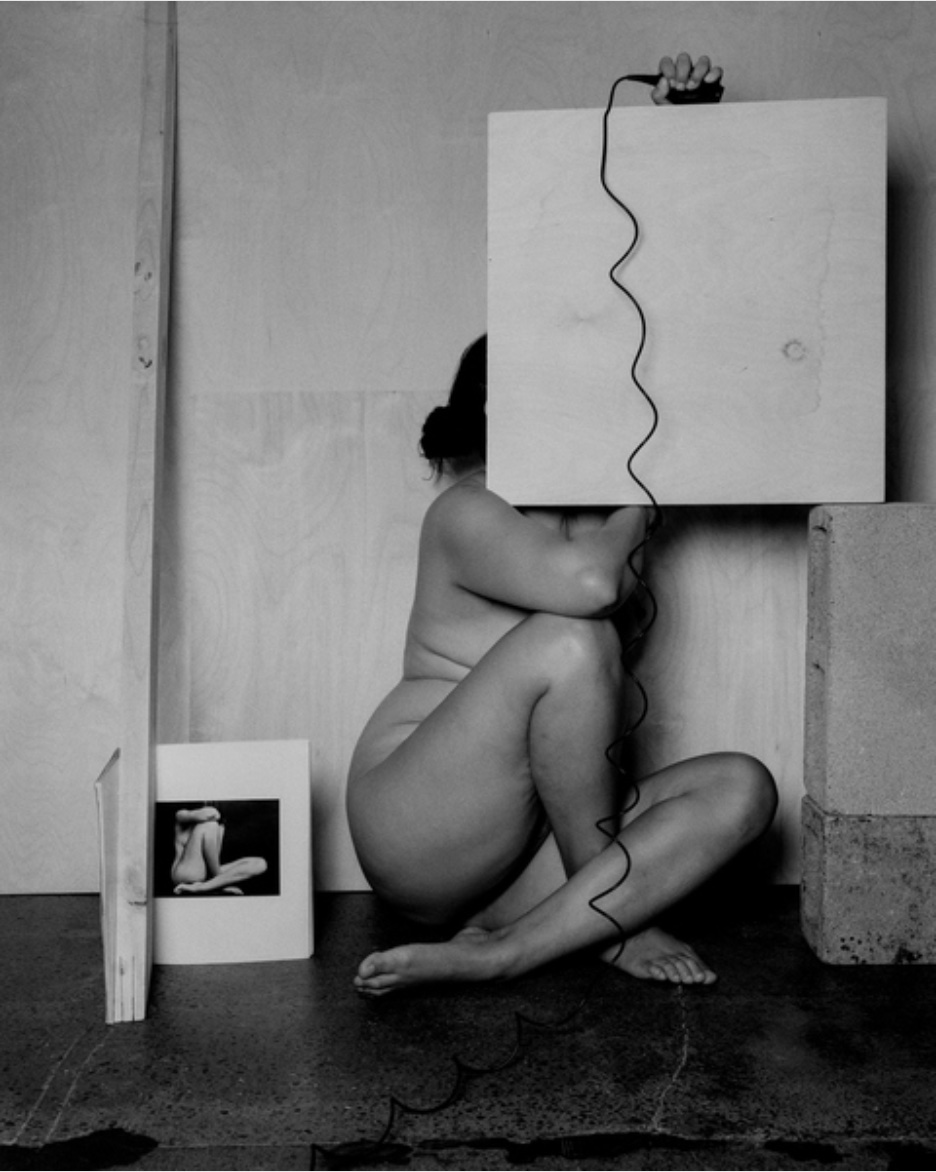

Tarrah Krajnak’s body of work, Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes, seeks to destabilise this canon of photographic history. In positioning herself alongside Weston’s nudes, Krajnak reenacts the negation of the model in the original image. The performance questions both the historic position of the female model while referencing and affirming Kajnak’s Latin American identity. The photographs become instilled with a considered, multi-layered structure, calling the viewer not just to comply with the images at hand, but to unweave the conceptual layers of thread which hold them together. They become, what Mark Sealy eloquently expresses in a recent interview with Caroline Molloy for 1000 Words “a thinking with images, rather than thinking for them”.

Evolutions in the photographic medium, such as the nude, are full of essential discourses that demand our attention. Krajnak’s images are an example of how artists can question the implicit structures embedded in history, and how this opens new avenues of reference and conversation, engaging our present selves in the necessary task of continuing to see, think, and act differently. Tracing the then and now of this phenomenon illustrates how extensively our perceptions of the human body have progressed. Now, we can only revel in the anticipation of what may come next.