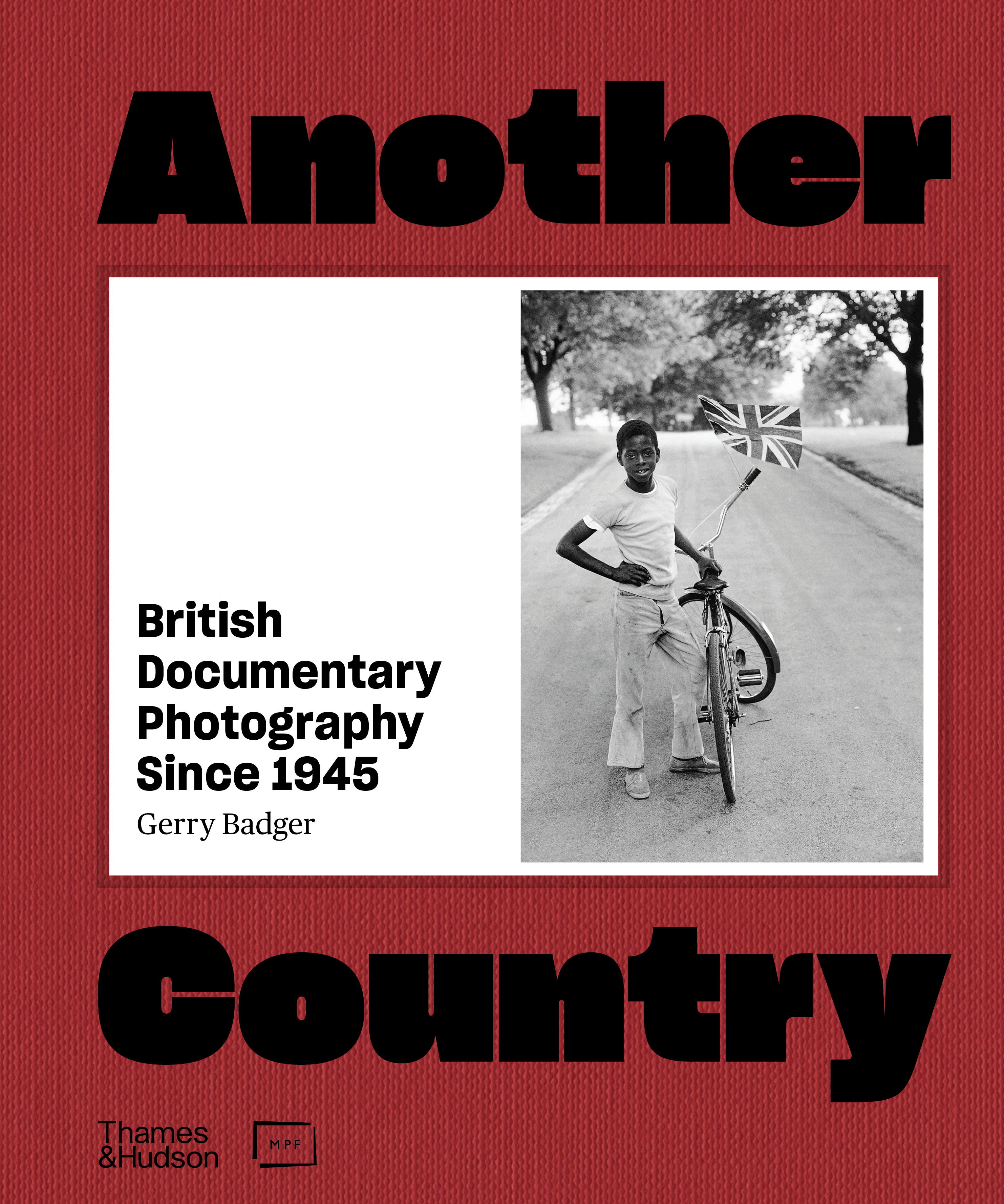

This danger lies not in the familiar images of post-war Britain themselves, but in the idea that such images represent the universal experience of the time. In an effort to address this, Another Country: Documentary Photography Since 1945 also explores the points of view of forgotten or previously ignored photographers, focusing particularly on the contribution that immigrants have made to British photography.

“Going all the way back to the 30s, Jewish photographers fleeing Nazi Germany made up most of the roster at Picture Post,” Badger explains, referring to the pioneering photojournalism magazine which, from 1938 to 1957, was considered the UK’s answer to Life. “It’s these and other immigrants talking about the society that they found themselves in – that’s the book’s other big theme.”

However, the book’s key theme – and the thread which holds together the work of photographers from Nadav Kander to Nigel Henderson – is the closing of the space between ‘documentary’ and ‘art’ photography. The genres are, Badger says, one in the same – both are simultaneously the fiction and the truth of each photographer.

“The best quotation I’ve ever heard about photography,” says Badger, “was Lewis Baltz, who said: ‘It is possibly useful to think of creative photography as a narrow but deep area, lying between the cinema and the novel’” .

Another Country: Documentary Photography Since 1945, is written by Gerry Badger, with contributions by Lydia Caston, Ekow Eshun, Clare Grafik, Hana Kaluznick, J. A. Mortram, Rianna Jade Parker, Simon Roberts, Lou Stoppard, Bindi Vora and Val Williams.

Published by Thames & Hudson In collaboration with the Martin Parr Foundation on 19 May 2022